These 5 Spooky Hikes are Way Scarier Than a Haunted House

Jagged mountain peaks seen through the window of a ruined log cabin at Boston Mine in Mayflower Gulch, Tenmile Range, Colorado. (Photo: Cavan Images/Cavan via Getty Images)

It’s Halloween season—decorative spiderwebs are sprouting on porches, graves (hopefully only decorative) festoon front yards, and everyone is prepping their costume for the one night of the year when it is socially acceptable to go out in public dressed like Legolas. But just because the weather is changing and the end of October is here doesn’t mean hiking season is over, too. Bring your weekend wilderness excursions into the spirit of the season with the five most haunted hikes in the country.

Crash Canyon, Grand Canyon National Park, AZ

At 11:30 a.m. on June 30, 1956, airline officials received a transmission: “Salt Lake, United 718–ah–we’re going in.” Moments later, United Airlines Flight 718 collided with TWA Flight 2 over the Grand Canyon, sending both planes plummeting earthward. The fiery wreckage struck Chuar and Temple Buttes near the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers, killing all 128 people aboard.

The tragedy sparked the creation of the Federal Aviation Administration, and the small ravine between the two buttes became known as Crash Canyon. It’s also the spot where ranger KJ Glover thinks she may have seen the passengers–almost 50 years after the accident. Glover told fellow Grand Canyon ranger and Haunted Hikes author Andrea Lankford that, as she camped between Chuar and Temple Buttes one night, she heard voices outside her tent. Peeking out, she saw more than a dozen people walking up the trail, in city clothes–button-up shirts and long dresses–and talking to each other as if nothing was unusual. When she climbed out of her tent to look around, they had all vanished. Could the passengers of Flights 2 and 718 be haunting their crash site? Officials identified only 29 of the victims; remains of the others were buried en masse, in four coffins, alongside a memorial in Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery.

An eerie coincidence also haunts Crash Canyon. It’s located near a sacred Hopi site called a sipapu–a gateway to the underworld, where the Hopi’s ancestors emerged long ago and where the dead can come back. “Native Americans are very superstitious about it. Rangers are very superstitious about it,” says Lankford. “Helicopter pilots won’t look down when they fly over it. There are stories of people who have gotten sick and even struck by lightning in the area.”

A skeptic, Lankford didn’t think much of the stories at first, but an inexplicable sense of imminent danger has scared her away every time she attempted to reach this sipapu. “I’ve tried to go there, but I get close, within a quarter of a mile, and I just feel really, really bad. I just turn around,” she says. “I don’t need to go to that place. I don’t think anyone should see it.”

—Anthony Cerretani

A Window to the Past

The rock layers of the Grand Canyon are more than just scenery—they offer a glimpse into the deep past of the region and the planet. The oldest rocks in the canyon, known as the Vishnu Basement Rocks, formed during the Proterozoic Era, which stretched from 2.5 billion to 541 million years ago. These rocks are mostly igneous (volcanic) or metamorphic, and the group is dominated by granite and schist. The middle layers of rocks, known as the Grand Canyon Supergroup, are only slightly longer but completely different geologically: this group is mostly sandstone and mudstone and formed in a shallow sea. The easiest to spot are the reddish layers of the Paleozoic Strata, which formed several million years after the lower layers in another shallow sea. These layers are filled with fossils of corals, small fish, and brachiopods.

The Trail

Start at the Tanner Trail trailhead at Lipan Point. This steep and unmaintained trail has over 4,000 feet of elevation change as it drops to the canyon bottom, gets unusually hot and has no water sources besides the Colorado River, so make sure you are well prepared and have experience in the canyon before heading down. Much of the path is unstable, especially the descent to the river, which was established by the pioneers and is little-used by modern hikers. Just above the Tanner Rapids at mile 9, join up with the Beamer Trail (also unmaintained) and follow it another 9 miles up the Little Colorado to the crash site.

Lake Crescent, Olympic National Park, WA

Maybe they were intrigued by a dark mass bobbing in the water near Sledgehammer Point. Or maybe it was a small, white flash at the surface that caught their attention. Or perhaps they simply cast a line for steelhead and were surprised to discover a 5-foot-long bundle on the other end. But for some reason on a day in July 1940, the two trout fishermen reeled in a nearly perfectly preserved corpse. Lake Crescent had surrendered one of its secrets.

Lake Crescent is nestled in a glacial valley south of the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the northern end of the Olympic Peninsula. Four-thousand-foot peaks rise on either side, as if to guard it—and maybe they are. The native Klallam and Quileute people tell a story of a once-beautiful region that was marred by war. Mt. Storm King, which soars over the lake’s southern banks, grew angry at the tumult and threw a chunk of rock from its peak into the river valley where the tribes were fighting. The boulder killed every one of the battling tribespeople and dammed the water, creating an undisturbed, crescent-shaped lake.

There’s some historical truth to the legend. Geological surveys indicate that a massive landslide decimated the area 8,000 years ago, effectively separating Lake Crescent and Lake Sutherland. One result of the partition is the former’s crystalline water. Without major inflows, Lake Crescent lacks the usual amounts of plant nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, preventing algae growth.

It’s no wonder a floating body looked so out of place in the clear water.

The two fishermen, brothers, reeled in the corpse. It was wrapped in a gray, striped blanket and bound with rope, but tears revealed a shoulder and a foot, both so pallid the body looked less a woman than a mannequin.

“It’s like a statue,” Sheriff Charles Kemp later concluded after the coroner’s examination. “The flesh has turned to some rubber-like substance.” There was no odor, nor any sign of decomposition. Something about Lake Crescent’s unique makeup had not only preserved the body—including a ring of still-purple bruises circling the girl’s neck—but had also actuated a chemical process called saponification, essentially converting the tissue into soap. What remained was the body of a woman in her mid-30s, around 5 feet, 6 inches tall, obviously strangled, and, to an extent, easily identifiable: Hallie Illingworth, missing for three years.

But Illingworth was only one of Lake Crescent’s victims. In 1956, an ambulance careened off US 101 at Meldrim Point, plunging into Lake Crescent, killing one. In 2002, a 1927 Chevy was discovered in Lake Crescent’s depths, finally closing the case on a couple that had been missing since 1929. They were entombed in Lake Crescent’s icy water for 73 years. In a chilling interview that was released by the FBI in 2013, convicted serial killer Israel Keyes insinuated that he’d dumped his victims in the cursed lake: “You guys know about Lake Crescent in Washington, right?” he taunted his interrogators.

Who knows how many secrets Lake Crescent hides?

“If you could ever get down [into the underground stream that flows from Lake Crescent to Lake Sutherland],” said Dr. Charles P. Larson, a Tacoma-based pathologist who assisted with the Illingworth examination, “you would probably find from 50 to 100 bodies, all of which have turned to soap.”

—Maren Horjus

Above it All

There’s more than just corpses here. The hundreds of species of moss in the Hoh Rainforest don’t limit themselves to the ground. Thick mats of moss and lichen build up on the trunks and branches of trees until they’ve trapped enough dirt to support other flora, like ferns and huckleberries (and occasionally smaller saplings). These are known as epiphytes, plants that grow on another plant but aren’t parasitic. They play an important role in the rainforest’s nutrient cycles, and provide food and shelter for some species of birds and flying squirrels that spend almost their entire lives in the canopy.

The Trail

The 11.2-mile out-and-back Spruce Railroad Trail runs along the shores of Lake Crescent, giving you plenty of chances to look out at the clear blue water and wonder what lurks underneath. It’s open year-round to hikers and cyclists, who can extend their trip on the bikepackable Olympic Discovery Trail. With little elevation gain and no intersections, this former railway site is an easy hike for the whole family.

Boston Mine, White River National Forest, CO

This may be a ghost town, but it sits right on a prime piece of real estate in this dramatic mountain basin. A ragged sawtooth ridge backdrops this collection of ruined log cabins and abandoned claims, peaking at almost 14,000 feet before dropping into steep chutes and rocky cliffs.

Boston Mine has been abandoned for much longer than it was ever occupied. Miners founded the town in the late 1800s following the discovery of a thick vein of gold ore in the adjacent mountains, building out homes, a boarding house, and trams to ferry their prize out to civilization. Unfortunately, it turned out the project was a bust: The ore wasn’t pure enough to make mining it economically viable, so the would-be prospectors went on their way. As the inhabitants abandoned their homes and town, the buildings fell further and further into disrepair, roofs collapsing in and walls cracking apart. Some of the derelict buildings are even sinking into the marshy ground. With century-old, rusting mining tools scattered around and ragged doorways creaking in the wind, this hike feels like a prime spot for a horror movie—with the added bonus of really spectacular mountain scenery.

—Adam Roy and Kristin Smith

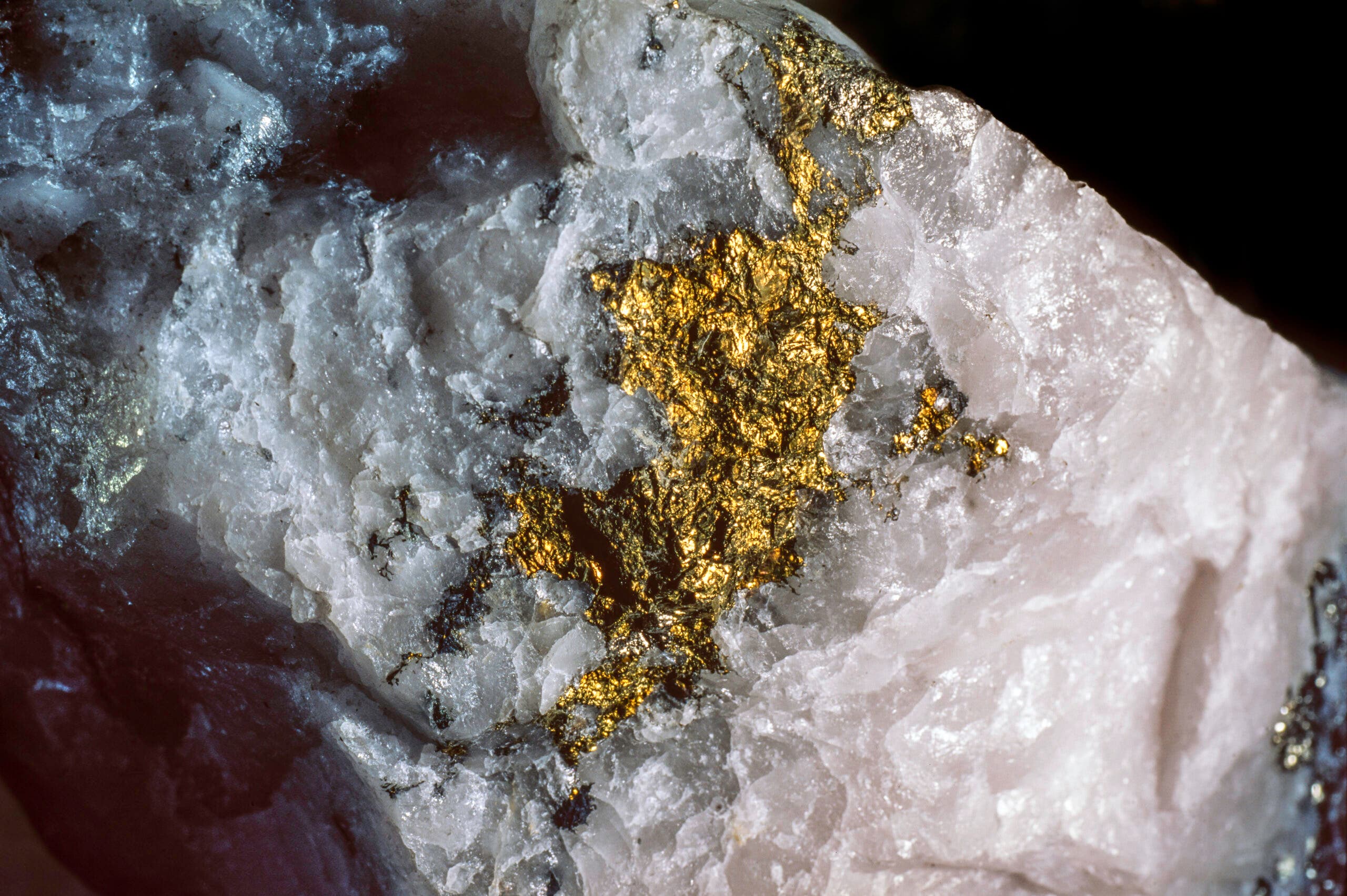

There’s Gold in Those Hills

Though the 1890s miners didn’t have any luck (and neither did a second wave in the 1980s), there really is gold at Boston Mine. Geologists estimate that there is between $15-50 million of gold in deep veins running through the mountain. That wealth, though, is going to stay locked away, preserving the wilderness landscape for future generations: in 2009 Summit County Open Space and Trails Department paid just under a million dollars to buy up all the mining claims to the gold, and the former owners of the claims gave up all of their mining permits to ensure the preservation of these mountains.

The Hike

Visiting the remains of the town requires a moderate 5.6-mile round-trip hike—short enough to be easily accessible, but just long enough that it doesn’t get too crowded. Starting at the Mayflower Gulch Trailhead, follow an old Jeep road gently up through mixed conifer forest. Around Mile 2, look on your right to see the remains of the tram line that miners would have used. Shortly after that, the forests open up to reveal Mayflower Gulch, the town, and beyond that, 13,958-foot Fletcher Mountain and 13,950-foot Pacific Peak. Follow the trail past a gate to the remains of the cabins (watch out for protruding spikes from the collapsed walls) and pose for a picture through the window. Head back the way you came, or add on some extra value with an ascent of Atlantic Peak or Fletcher via the rubbly, class 2 ridge. (Climbing in winter? Bring crampons and watch your step.) —Adam Roy

Mt. Washington, White Mountain National Forest, NH

New Hampshire’s tallest peak is not very high–6,288 feet–by mountaineering standards. And the ascent is not particularly technical; you can walk up on the country’s oldest mountain trail. But don’t be fooled: Wind gusts up to 231 mph and temps as low as -50°F have been recorded on Washington, and more than 130 people have died on the mountain since 1849.

At least some of those souls have stuck around. They’re known collectively as The Presence, because there are too many ghosts to name just one. Some are apparently friendly, like Red “Mac” MacGregor, one of the early loggers who helped build Carter Notch Hut and managed it in the 1920s–before settling in as the resident ghost. And at Lakes of the Clouds Hut, visitors will see a pair of boots nailed to the wall; legend has it that the boots had to be stopped from walking around by themselves after their owner died from a fall while hiking (shortly after serving on the hut crew in the late 1970s).

But not all of the spirits are so benign. In 1900, William Curtis and Alan Ormsbee died in a storm while pushing toward the summit. Now, if hikers criticize the duo’s decision to pursue the peak, an invisible force pushes or strikes them. And in Haunted Hikes of New Hampshire, Marianne O’Connor relates the tale of an Appalachian Mountain Club member known only as George who went to open the Lakes of the Clouds Hut, alone, in the AMC’s early years. Standing in the hut, with the windows still boarded up, he sensed something watching him. He turned and saw a crowd of grotesque faces leering at him, the ghouls filling each of the boarded-up windows. The faces pushed toward him, through the glass, bearing down on him. It was the last thing he could remember. When searchers found him two days later he was huddled under a sink muttering, “Get me the hell out of here.” —Anthony Cerretani

Science on the Peaks

The observatory site that clocked the mountain’s record 231 mph wind in 1934 is still home to an active weather station, which conducts weather and climate research in partnership with universities and laboratories working on anything from product testing to cosmic ray monitoring. One of very few staffed mountaintop research stations in the world (and the only one of its kind in the western hemisphere), the observatory takes advantage of Mt. Washington’s position at the convergence of three different storm tracks to study some of the worst weather on Earth. Scientists in several different disciplines also use the datasets for wind, rain, visibility, and several other atmospheric metrics generated by the observatory and the surrounding network of weather monitoring stations for weather pattern analysis and climate modeling.

The Trail

The most popular route up Mt. Washington follows Tuckerman’s Ravine from Pinkham Notch, coming in at 7.4 miles round-trip. Before starting to climb, the trail passes the Hermit Lake shelters at mile 2.4, a good place to pause for views back over the ravine and a small waterfall. The shelters themselves have potable water available in the summer, and can be reserved through the Appalachian Mountain Club. Yellow arrows mark the first part of the trail, then cairns take over. The climbing intensifies over the next 1.5 miles of trail, finishing out the 4,242 feet of elevation gain to the summit, where you can bask in a 360-degree view of the White Mountains. Hikers use caution: While this is a popular trail in the summer, it can be icy and dangerous in the winter; prepare accordingly.

South Rim Trail, Big Bend National Park, TX

Spanish soldiers, Apache chiefs, gunslinging cowboys. They’ve all died here, some brutally, some gloriously, some mysteriously. All contributed to the name Chisos, which is thought to derive from the Spanish hechizos, meaning “bewitchments” or “enchantments,” or from the Castilian chis (“clash of arms”), due to reports from early visitors that they heard the ghosts of Spanish soldiers.

The most famous of the fallen: Chief Alsate, the last leader of the Chisos Apaches, who was killed by a Mexican firing squad in 1882. “They say that when his body hit the ground, the mountains shook,” says Andrea Lankford, author of Haunted Hikes. Soon after his death, Alsate allegedly appeared to Lionicio Castillo–who had betrayed the chief to Mexican officials–and terrified him so badly that Castillo himself vanished. Some say Alsate is also responsible for the Marfa lights, glowing orbs that are regularly seen in the desert northwest of Big Bend.

Alsate has plenty of company. As recently as 1978, hikers reported seeing the apparition of a man wearing a serape in Bruja (“witch”) Canyon. According to Tales of the Big Bend, others have seen the daughter of a Spanish don who drowned herself in a pool rather than succumb to her bandit captors as well as La Llorona, or the wailing woman, who drowned her children in a fit of rage and now roams the Rio Grande in search of them.

Even a spectral bull inhabits Big Bend. In 1891, Fine Gilliland and Henry Powe fought over the coveted animal–which had no brand–and Powe died in the ensuing gunfight. Shortly after, a Texas Ranger shot and killed Gilliland. Following the deaths of both would-be owners, the bull was finally branded: “Murder.” The phantom bull now roams Big Bend as a harbinger of death and murders to come.

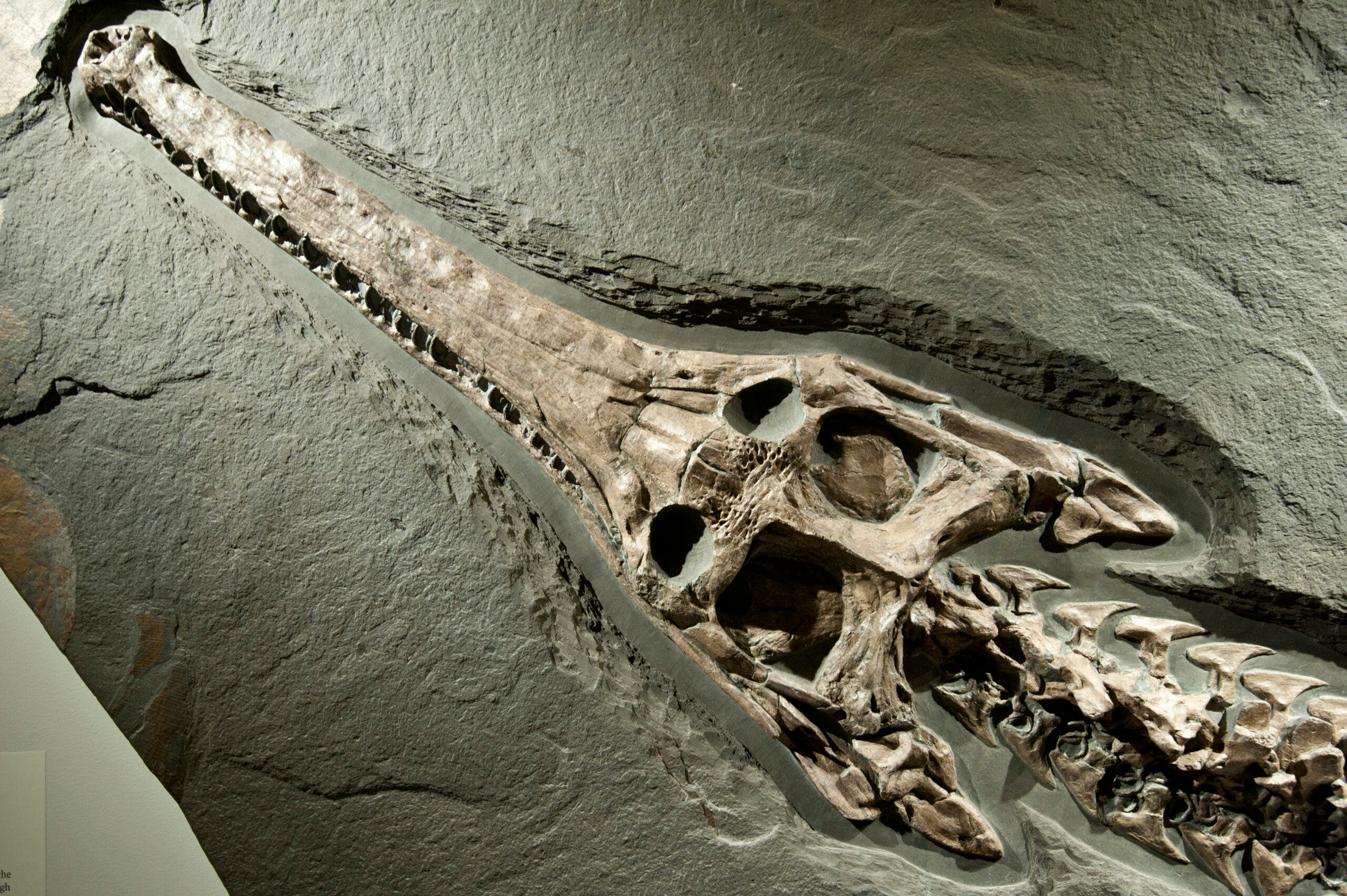

A History of Dinosaurs

The fossil record in Big Bend National Park is both the most diverse and spans the longest time period of fossils in any national park. Some highlights include a pterosaur with a 36-foot wingspan (the species is the largest flying animal of all time) and 40 to 50 foot long giant crocodiles with 6-inch teeth known as Deinosuchus. Over 90 dinosaur species have been discovered here, and paleontologists continue the work today.

The Trail

Start from the Chisos Basin Trailhead. On the Laguna Meadows Trail, gradually ascend 7.8 miles through mountain meadows and sheer mountain faces. The trail ends along the top of the South Rim, where backcountry sites are available. You can retrace your steps to the parking lot or descend on the steeper Pinnacles Trail for a different view of the mountains.