Searching For Pops

Day 1: Monday

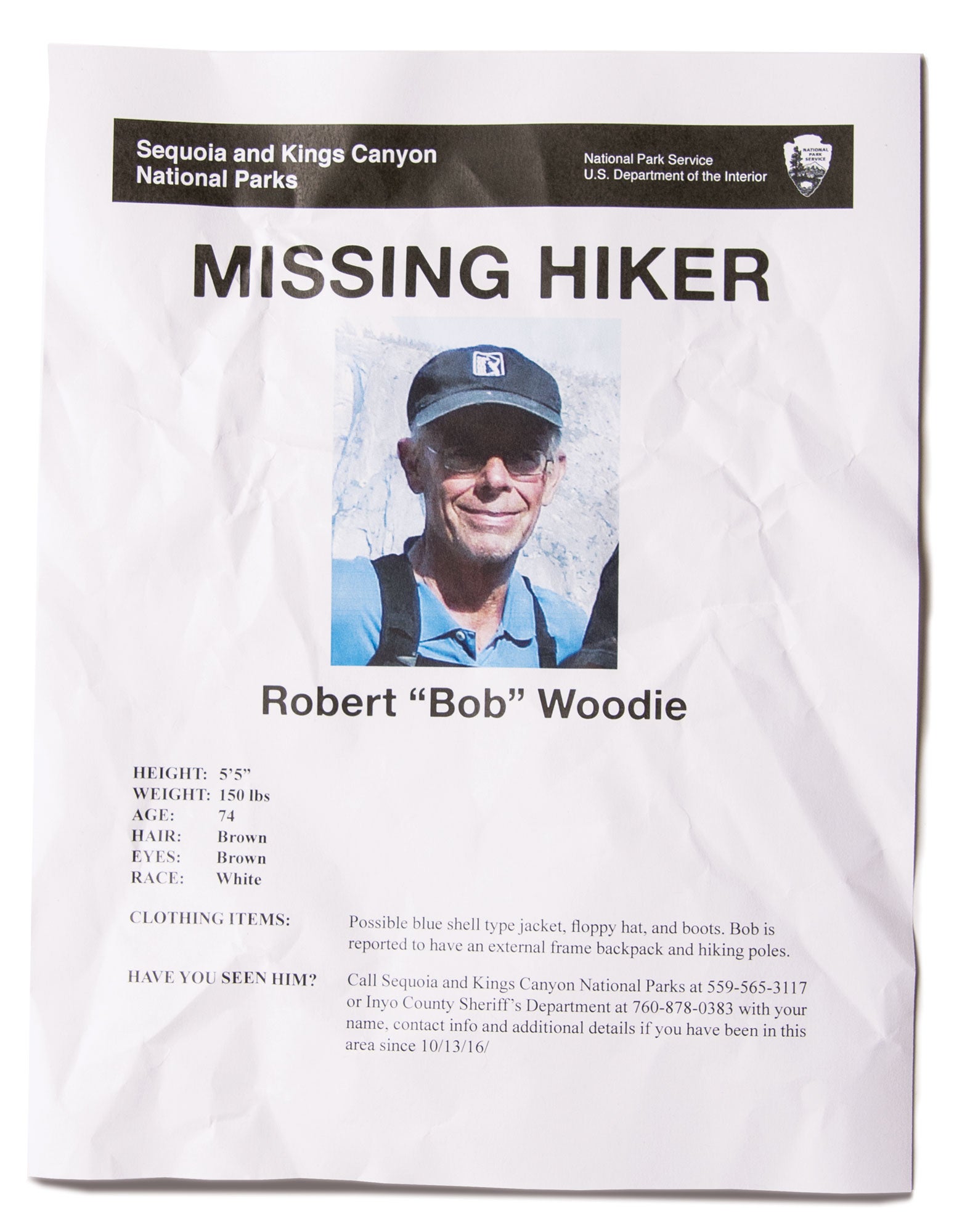

Pops was supposed to call late Sunday night. After a three-day solo backpacking trip in the eastern Sierra, he had planned to fish Sunday morning, take the rest of the day to hike out, and arrive at the trailhead well after dark. When noon rolls around on Monday, October 17, 2016, and he still hasn’t called, my brother Tim and I are concerned but not alarmed. Pops, 74, is an experienced backpacker, and it’s not the first time he’s gone hiking alone.

We make some calls to the Bishop Ranger Station, trying to determine if he’d changed his itinerary, or maybe emerged from the wilderness without calling. We spend much of Monday waiting, and finally hear back that Pops had secured a backcountry permit for the South Lake trailhead indicating he’d be out Sunday, as we expected. Our anxiety grows as several more hours pass. At 10 p.m., a ranger calls to confirm: Pops’s car is at the trailhead. He’s now more than 24 hours overdue.

Tim and I don’t need to discuss our plan. We’ll grab our gear, get a couple hours of sleep, and drive six hours to Bishop from our homes in the Los Angeles area. We should be there by the time Search and Rescue teams are heading out. Fortunately, they know where to start looking. Pops had checked in with his SPOT beacon on Saturday night, so we have his coordinates. He camped at Barrett Lakes, in the backcountry west of Bishop. We’ll find him quickly, I think. I hope.

My two brothers and I started backpacking with Pops as kids. We would often be out in the Sierra for more than a week, fishing at least an hour a day. I remember one trip during which Pops told us how he and his cousins used to hide rocks in each other’s packs. Naturally, we spent the week playing the same prank on each other. On the hike out, we were able to sneak a heavy rock into Pops’s pack. After a few miles, we finally snickered a confession. But the joke was on us: Pops hiked on with the extra weight like it was nothing.

Back then we called him Dad. I started calling him Pops about 15 years ago; it just seemed to fit the athletic father of three and grandfather of five. Others know him as Bob Woodie. Everyone agrees he is a kind man, a great dad, an engaged grandfather, a doting husband, and a lover of the High Sierra. He enjoys backpacking with others, but if no one is able to go with him, he’s never hesitated to go alone.

Day 2: Tuesday

Tim and I arrive in Bishop at 8:30 a.m. and meet with officials of the Inyo County Sheriff’s Search and Rescue division, who tell us that we can’t be a formal part of the search effort. But they’re sympathetic to our situation, and make it clear that we’re free to look on our own. They loan us radios so we can stay in contact with the SAR teams.

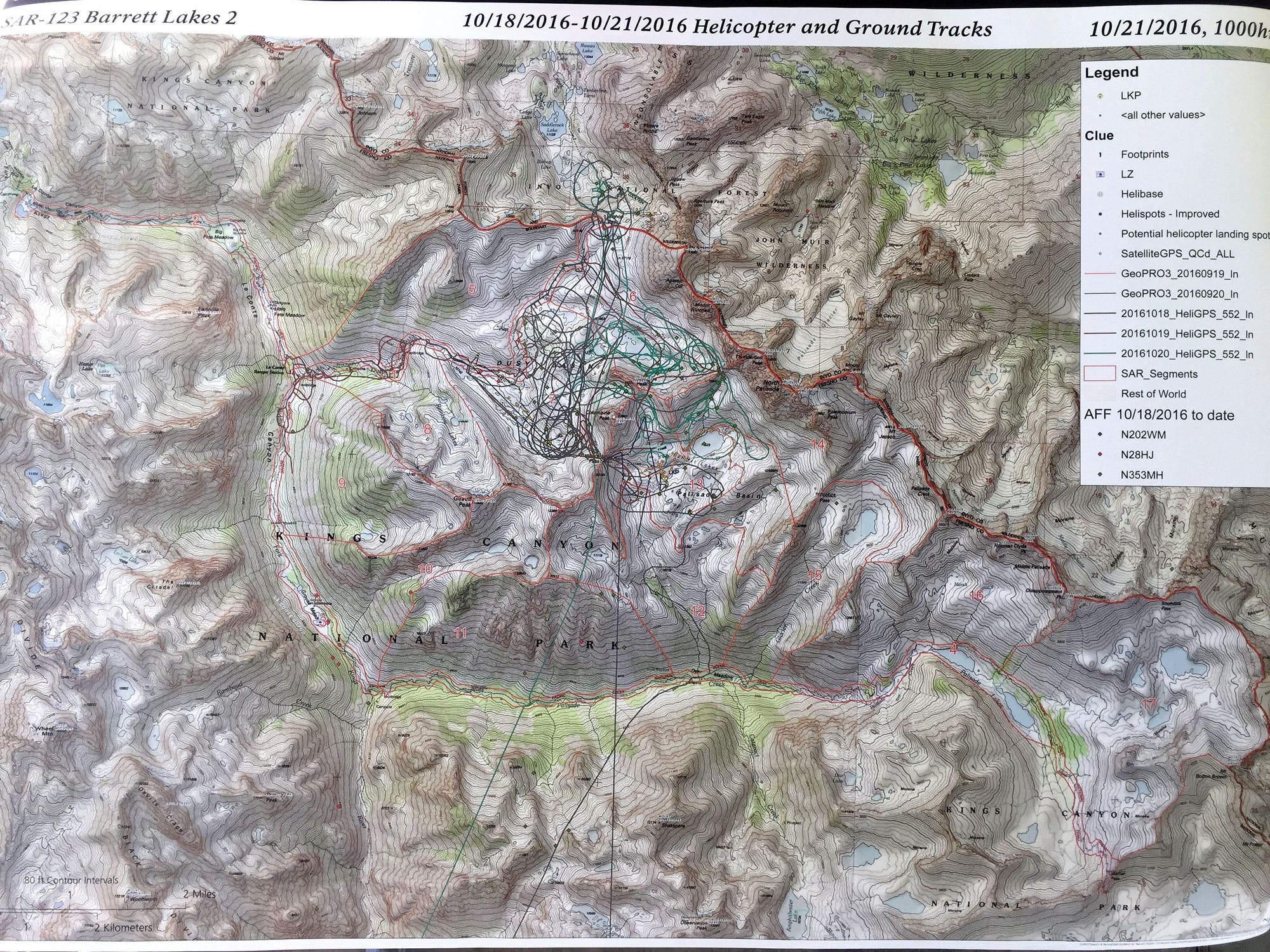

We pore over the topographical map and quickly determine that, from Barrett Lakes, there are only two likely routes Pops would have taken to return to Bishop Pass and the trailhead. Both are off-trail, exponentially increasing the difficulty of pinpointing his track. He would have traveled as far as 6 miles from the nearest trail, and if he’d strayed from the logical routes . . . The thought makes me feel sick.

At the South Lake trailhead, my heart sinks to see Pops’s car parked there. It emphasizes the severity of the situation.

If we can take consolation in anything, it’s that, after a wintry storm Sunday, the late-October weather is clear and calm. It’s the shoulder season, so I know the nights will be bitter cold at higher elevations, but at least it’s dry.

Tim and I start up the trail and immediately begin to feel the elevation. Both of us have just come from sea level, and we’re climbing to 12,000 feet. We suffer from pounding headaches.

It’s 6 miles to Bishop Pass, and about an hour before reaching it, Tim spots a tan- and rust-colored tent exactly like Pops’s about 50 yards off the trail. We notice the bear canister set well away from the tent just the way Pops would have done. We both rush to the site. The location—in plain view, right off the trail and so close to the trailhead—doesn’t make sense, but maybe he got injured on the way out. What else could explain his delay? We’re sure we are about to find our dad. A blue backpack the same color as Pops’s lies next to the tent and my heart jumps. But then I see flip-flops he would never wear and a bottle of whiskey he would never touch. The unoccupied tent is not his.

My father always led a simple life; neither he nor my mom drank or smoked. I never even heard my father curse. His greatest vice is his sweet tooth. It’s one I inherited from (and share with) him. We favor the chocolate chip cookies from Subway.

At the pass, we meet three SAR volunteers wearing bright-orange jackets. They haven’t found any clues; our conversation is short but hopeful. The sun is shining and it’s still less than 48 hours since Pops went missing.

We continue a mile down the trail into Dusy Basin. Tan-and-gray granite sweeps up the slopes. A dusting of snow from the previous day’s storm contrasts against the deep blues of lakes and sky. Days are short this late in fall, and it’s nearly dark when we arrive. We find a campsite but it’s hard to go through the backpacking routine—pitch a tent, cook a freeze-dried dinner, get into sleeping bags—knowing that Pops is out there somewhere, in trouble.

Day 3: Wednesday

Last night’s rest was fitful, a combination of worry and altitude sickness. The temperature dropped to about 15°F, and I needed to wear every piece of clothing I packed to stay warm. Tim and I try not to dwell on what Pops might be going through if he’s without shelter and insulation right now. In recent years, he’s been forgetting key items like a sleeping pad or long underwear. I pray this is not one of those times.

Fortunately, we have plenty to do to keep our minds busy. Thanks to the radios, we know that a helicopter on the west side of Knapsack Pass had spotted tracks in the snow. Knapsack and Thunderbolt are the two off-trail passes Pops might have targeted on his return from Barrett Lakes. (A SAR team had already checked the campsite there, and Pops’s gear was gone, so we know he went astray while hiking back on Sunday.) Tim and I decide to spend the day hiking to Knapsack Pass and back.

It’s good to be in the backcountry with my younger brother again. I’m 53 and Tim is 51, and the demands of work and parenting have made backpacking opportunities fewer and farther between. Like Pops, if Tim is in pain he won’t show it on the trail. He was always tough during our childhood trips, when we used to hike off-trail as much as on. We adhered to the reliable philosophy: The harder it is to reach a lake, the bigger and more plentiful the fish will be.

I enjoy creating my own route by scanning the terrain immediately in front of me. This necessitates constantly lifting your head to check progress instead of simply keeping your eyes on a path. It’s much slower than hiking a trail, but you’re constantly reminded of the beautiful surroundings.

After about 3 miles, less than an hour from Knapsack Pass, the rocky terrain becomes so difficult that Tim and I need to store our trekking poles in our packs. Many times we have to use both hands to hoist ourselves up. I doubt that Pops would come this way with a full pack. Too cumbersome.

I’m not surprised when we find nothing at the pass or on the other side. On the way back to our camp in Dusy Basin, I take some comfort in knowing that Pops had likely followed through on his plan to fish Sunday morning before heading back. It’s an obsession with him. He takes pride in waking before dawn so he can make his coffee and cast a line by first light. After a hard hike, instead of relaxing in camp, he will often fish until dark. Ironically, our catches always seem to be about the same despite all the extra time he puts in. But I know for him it’s not about the numbers; it’s his own form of spirituality.

Day 4: Thursday

After the scramble to Knapsack Pass, I’m positive Pops would not have taken that route if he could help it. This is his fourth year in a row hiking into Barrett Lakes, and by now he would have figured out the fastest, easiest, and prettiest route. We decide to move our basecamp and search the route over Thunderbolt Pass, now the most likely option. There are SAR teams crisscrossing the wilderness (at its peak, the effort includes 120 searchers and five helicopters) and we check in via radio on the way to Thunderbolt.

We learn that a helicopter is on the way; the search leaders down in Bishop want us to return to help identify more of Pops’s clothing and understand his backcountry habits. They also need access to his car for scent articles so they can deploy dog teams. It sounds plausible but I’m suspicious. Perhaps they want us out of the way of the professional searchers. Looking for Pops myself—instead of waiting for word from others—has so far saved me from becoming a total wreck.

The flight down to Bishop takes barely 10 minutes, but it’s a revelation. A dozen lakes you can’t see from the trail parade by in rapid succession. I think of how Pops would love to be in the seat between Tim and me. He has spent so much time exploring this valley; he would be fascinated by the view of it from the air.

At the landing pad in Bishop, a Park Service employee named Jessica, who is coordinating the search efforts, suggests we get lunch at the airport restaurant while she arranges a conference call with the search leaders. Just then, our lifelong buddies Steve and Danny show up. They’ve known Pops since we were kids. After hearing the news, they decided to drive up and help the search.

We’re drinking sodas, chatting with them, and waiting for food when I’m overwhelmed by the absurdity of relaxing and enjoying a hot lunch while Pops could still be alive and in trouble. I head over to the ranger office and ask Jessica to get the conference call organized. We wait for the longest 15 minutes of my life.

After half an hour of answering questions about Pops, I get the officials on the line to promise that they’ll helicopter me and one other person back into the wilderness at the end of the call. I will regret not getting names to hold accountable.

We decide that Tim will stay behind and help with the search from the Bishop office, and that Danny will go up the mountain with me to continue searching the high country. That’s when the higher-ups renege on the helicopter ride, and we’re forced to accept Jessica’s offer to drive us back to the trailhead.

I’m deeply annoyed by the setback. We’ll have to hike back up to the alpine zone to resume the search. During the 20-minute drive, I let the scenery take my mind off the frustration. I remember making this same trip many times as a kid. After breakfast in Bishop, we would pile back into the car and Pops would steer us upward, from the wide Owens River Valley to the base of the high peaks. This time of year, aspens along the South Fork Bishop Creek glow a vibrant yellow.

The road dead ends at South Lake, already close to treeline, but it still takes more than four hours to climb back to Bishop Pass. The altitude slows Danny, just as it did Tim and I on the first day. We make camp well after dark, but I’m glad to be back in the wilderness. We lost two people searching for more than half a day. What might have been missed?

Day 5: Friday

The hike to Thunderbolt Pass is easier than the first route we tried, but it’s off-trail, and still slow and difficult going. We navigate across 2 miles of talus; it feels more like 12. The extreme angle means any misstep could lead to a long tumble.

On Thunderbolt Pass, we meet five different SAR teams, three of which came up from Barrett Lakes and the surrounding Palisade Basin, where search efforts are concentrated. This area has likely never seen so many people at once, and I can’t help but think how Pops would be appalled by the hordes.

By his own admission, Pops is a shy person. As a butcher, he was happy to work out of sight in the refrigerated confines of the supermarket’s meat department. However, his work ethic earned him promotions, and in the new roles he needed to engage more with customers. When I was in high school, he helped me land a job as a box boy, and I would sneak up and surprise him as he chatted with people. Watching him, you wouldn’t have known he was shy at heart. But for Pops, I always knew that the greatest appeal of the backcountry was the solitude.

Danny and I eat lunch at the pass with the other searchers. Seeing all of them gathered in one spot like this, and hearing about all the other teams spread across the area, starts to crack something inside of me. Too many days have gone by, too many teams have looked in too many places. Pops is gone.

I don’t know why, but the realization makes me tell Danny that if Pops had a mean bone in his body, I never saw it in five decades. Danny hugs me and I cry for the first time.

When we return to camp, I know what I want to do. I will make the trek to my Pops’s last campsite at Barrett Lakes, where I will camp exactly one week after he did. I tell Danny that I need some time alone to memorialize my father and that he should head home to his family. I help him pack his gear and watch him disappear down the hill.

For the first time on this trip I am alone. Another round of sobbing hits me. The Tim McGraw song “Humble and Kind” has been stuck in my head since Pops went missing, and now I listen to it on my phone. I know you got mountains to climb but always stay humble and kind. It brings comfort as I reflect on how lucky I am that the most humble and kind person I know is my father.

As an adult, I became keenly aware of his character when I went into real estate at the same time Pops retired from his career as a butcher. He started his own handyman business, and from the beginning just about all of my clients used Pops. Over the last decade, he spent more time with them than I did. Many of these customers are elderly, and while his visits usually involved plumbing or electrical work, they were as much social calls as repair jobs. He made a point of dropping in on older clients who lived alone, just to check on them.

Day 6: Saturday

I wake up feeling light, agile, and as capable in the backcountry as I ever have. Today I realize I’m no longer searching for Pops. I’m experiencing firsthand why he chose to return here four years in a row.

I pack up camp early, before the sun hits, just like Pops would. Even with gloves my hands are numb from the early-morning cold. The hike to Thunderbolt Pass warms me up, and I explore the most direct route, which is not the easiest. There are signs of three recent rockslides. But the traverse goes well, even with a full pack, and I’m convinced this is the way Pops would have gone. But then how did he disappear?

If only he hadn’t been alone. In recent years, I have hiked with Pops in Yosemite, Glacier, the Grand Canyon, and Yellowstone. But in that time I never joined him at Barrett Lakes. I see now that his regular spot has a beauty to rival its big-name competition. Granite benches terrace down to the water, creating an amphitheater below Thunderbolt Peak and Knapsack Pass, with views of the toothy Palisades. It’s stunning, and with each step I regret never sharing this area with him.

As I come up to the first and largest lake, I sense the excitement Pops would have felt arriving after such a long and difficult hike. He would have been giddy at the prospect of six beautiful lakes full of trout and set against a panorama of 14,000-foot peaks, an impossibly blue sky, and clouds straight from an artist’s easel.

At the edge of the first lake, out of habit, I look down for fish. In my mind, Pops is about 50 yards away, and both of us are about to cast. I now know those days will only be a memory and I am wracked by grief anew.

At the second lake, I run into a group of eight searchers. I thank each one individually, and tell them a little bit about Pops and how he loved this spot.

In the late afternoon, I reach Pops’s last known campsite. It’s located on a granite bench, flat as a board and big enough for a dozen tents, bordered on three sides by water. The ribbon-like lake is the prettiest one I’ve seen in the basin. The green water reflects the snow and Knapsack Pass.

On the way here I thought about what to do once I arrived, and now I have two tasks. First, I write “Pops” on the granite by making letters out of snow and take a self-portrait with the sign. I have a ton of people to reach out to when I get home, and this will help.

Next, I set about building a memorial out of stones. It takes an hour to find the perfect spot, on a little rock shelf overlooking the campsite. After wrestling 40-pound boulders into place, I’m pleased with the result: a 4-foot-high structure with a long triangular stone as a cap.

Day 7: Sunday

It’s time to return home. The weather is changing, winter is coming. The search is over.

It only takes me an hour and a half to reach Thunderbolt Pass. As I stand there for the third time, waves of sobbing overcome me as I look down on Pops’s beloved spot. It’s so windy now that I don’t bother wiping my eyes; the gusts dry them.

I take my highest line yet between Thunderbolt Pass and Bishop Pass. Now on my fourth trek between the two passes, I am completely certain this is the route my dad took. It’s not an easy scramble, but it’s doable with hiking poles and you don’t lose elevation just to gain it back. There are sweeping views with every step and Pops always loved vistas. But it’s not without hazards. Passing right below massive peaks, a hiker would have little time to react to falling rocks, and I note again the signs of recent slides. I encounter a dozen more searchers between the passes, but they have no news except this: The SAR effort has been officially called off due to storms in the forecast.

On the final descent to the trailhead, I think about my father’s quiet wisdom, and what he might have said now. I recall a time when I was a teenager, and I was worried about something as we played a game of H-O-R-S-E on our driveway basketball court. He told me that the only thing you should worry about is doing your best. When you know you’ve done your best, the rest is out of your control and silly to worry about.

I play the week back in my mind, recalling all the searchers, all the miles hiked. There will be much sorrow to come. But as the snow starts falling, I think, We did our best, Pops. We did our best.

Editor’s note: On July 8, 2017, hikers found Bob Woodie’s body 100 yards from the trail near Bishop Pass. It appears he had taken shelter from extremely strong winds—gusts of 100 mph were recorded that day—among boulders. He had his gear with him but succumbed to hypothermia. Windblown snow likely covered him and his tracks, concealing his location from searchers. The Bob Woodie Memorial Endowment, established in partnership with the Sierra Club, will support efforts to connect underprivileged kids with nature.