When the Mayor of the Mountain Disappeared

Sam was late.

Evening had slipped into night, night had faded into dawn, and the driveway in the Culver City neighborhood of Los Angeles where Sam’s car normally sat remained empty.

It wasn’t unusual for Sam to keep odd hours, but his wife Sunny and his son David worried all the same. What in the world was a man of Sam’s age doing climbing mountains?

It wasn’t the first time Sam had stayed out overnight—he would sometimes sleep in his car so that he could hit the trail at sunrise—but it was the first time he hadn’t returned home without calling. The next morning his phone was going straight to voice mail. Sunny was worried enough to call one of Sam’s friends to see if he had heard from him. He hadn’t.

David, who lived just a few miles away from his parents, tried to fight the anxiety by reminding himself how tough his father was. Sam had survived the L.A. riots of 1992, been robbed at gunpoint, and had hiked millions of vertical feet, many of them after his 60th birthday and on the most difficult trails in Los Angeles County. He had come through it all with the grit of those who seek better lives in America. And he had always come home.

Sam clocked more miles the older he got. At age 75, his current obsession was Iron Mountain. With a 7,200-foot ascent up a rock-strewn StairMaster, and 15 miles round-trip, it is considered by many the toughest dayhike in the San Gabriels, a mountain range imposing enough to halt L.A.’s sprawl on the northern edge of the city.

Sam was known to set grand goals and it surprised no one when he vowed to climb Iron Mountain 100 times in a single year. And having already summited dozens of times, he was on course to reach the goal before his 76th birthday. He was a year-round creature of the mountains, so much so that it was impossible to imagine anything happening to him. And so David and Sunny did what Sam would have wanted them to do—they waited.

Finally, Sam called from the road to say he was on his way home. And, sure enough, a little after noon, he strode through the front door as if time were as loose and casual as he considered age to be. He was 5’5” standing straight, which he always did, and his slightly oversized blue jacket draped over a wiry, mountain-made frame. Sunny doesn’t remember being angry with him.

Sam explained to her in Korean that he’d become benighted without a cell signal, but had stumbled across a perfectly comfortable abandoned cabin, stayed the night, continued his descent at first light, then jumped in his car for the nearly two-hour drive back across Los Angeles. And less than 24 hours later, he’d do the drive in reverse, returning to the base of Iron Mountain.

Over two decades, Sam’s dedication to the mountains had slowly become the most important thing in his life. His wife, four children, and five grandchildren had watched him evolve from hiking enthusiast to evangelist, from an every-Sunday Catholic to someone who’d skip church to climb a mountain.

Indeed, Iron Mountain was only one of his obsessions, and not even the most potent one at that. Sam had climbed 10,064-foot Mt. Baldy, the tallest peak in Los Angeles County, nearly 300 times by the time he even set foot on Iron Mountain. And he’d vowed to climb Baldy 1,000 times before his 80th birthday.

“The first time he told me about his goal, my reaction was ‘why?’” David recalls. “‘Why do you need to do that? What does it mean?’”

Sam was an expert at uphill climbs. When he came to America in 1981, he arrived as Seuk Doo Kim, 43 years old, a well-respected manager for the Bank of Seoul, and a father of four. After 17 years working in the South Korean capital, he was offered a position managing an American branch that served the growing Korean-American population in Los Angeles. So he became Sam.

Three years later, when his job transfer expired, he resigned so he could remain in his adopted home, later attaining citizenship in 1988. Together, Sam and Sunny opened a gas station and convenience store on the corner of Venice Boulevard and Vermont Avenue, south of Koreatown. It was a dangerous time in a dangerous part of the city, but Sam and Sunny manned the cash register 15 hours a day, seven days a week, for nine years straight. It was a routine punctuated by the occasional robbery, none scarier than the day Sam had a gun pointed at his head. That nearly broke him.

Sam began to seek strength through a higher power. He grew up without religion, but his wife Sunny became Catholic in her 20s and her invitations to join her in church began to sound comforting. (Sunny, now in her 80s, speaks little English and chose to translate her thoughts and memories through her son David for this story.) Sam was baptized in his 50s, became head of the lay ministry at St. Agnes Church in Koreatown, and busied himself welcoming new people to the flock. He and Sunny alternated going to mass on Sundays in order to keep the convenience store staffed.

Business was good, but after a decade without a break, Sam grew weary of the toil, the tension, and the violence. He and Sunny sold the convenience store and opened a gift shop in Burbank, a part of L.A. that might be described as boring if it weren’t for its famous film studios. They no longer felt obligated to personally staff the store at all business hours. Their newfound calm—and leisure time—compelled Sam to reconnect with his past. He began to daydream about hiking the hills beyond the city.

He started out hitting the trail on weekends and holidays. As Sam would tell anyone who would listen, Koreans have a special relationship with the outdoors. Seventy percent of the country is mountains and the trails around Seoul fill up with enthusiastic hikers every weekend. Hiking in his native country was an expression of national pride and Sam often reminisced about his own childhood spent galloping around the countryside where he lived.

At age 69, 13 years after opening the gift shop, Sam retired. He began spending every free moment he had in the San Gabriels, gravitating toward long uphill slogs that require as much mental toughness as they do quad and lung strength. But as he neared 70, Sam had more questions about his life than answers. His relentless pursuit of the American Dream left little time for looking inward. In church, he found community but little inspiration to reflect. So he went looking for answers in the mountains.

“My father was a very spiritual person and this became his time to reflect on his life,” David says. “He began to say he felt God’s spirit in the mountains more than at church.”

Sam first hiked to the summit of Mt. Baldy in early 2000. But it wasn’t until June 7, 2007, when he hiked to the top via the less-traveled—and less-forgiving—Ski Hut Trail, that he fell in love. He felt an instant bond with the mountain’s steep switchbacks and returned to hike to its summit every chance he got, quietly accumulating ascents. He found freedom there and peace like he hadn’t anywhere else. He was home.

Sam entered a new, freer phase in his life. He was finally able to give himself fully to hiking, often with Sunny by his side. The next year, in 2008, the two began making annual trips back to Korea to section hike the 450-mile Baekdu-daegan Trail. Sam later wrote a guidebook about the trail.

Meanwhile, he continued making his weekly—sometimes daily—pilgrimages to Mt. Baldy. By the end of 2013, David estimates that his father had climbed Baldy roughly 300 times (only Sam kept the true count). At the same time that Sam was becoming disenchanted with orthodox religion—and what he would call its “hypocrisies,” often referencing things like sexual abuse scandals—he was finding an alternative in the wilderness. He eventually told David that he had found a new way to show God how much he loved Him. “I really think my father was happiest at the summit of Baldy,” David says. “Sometimes he stayed there for hours, just sharing food and talking to other hikers.”

The camaraderie Sam found on the mountaintop extended to the quirky off-grid community in Baldy Canyon. Through brute repetition and an outgoing personality, he endeared himself to the locals.

He took a particular liking to a man named Dick Tufts, a former Marine and truck driver, who lived just above the Baldy trailhead in a small cabin with his black lab Bullet. Tufts is an impressive outdoorsman, even in his early 70s. But he and Sam shared more than stomping grounds. “Sam and I had both more or less given up on churches,” Tufts says. “I guess we sort of considered this our heaven.”

But while Sam got to know Tufts and other locals, his only regular hiking companion was Sunny, who has climbed Baldy at least a couple hundred times herself and says she could probably walk to the summit with her eyes closed. “It was fun—it’s what he always wanted to do,” Sunny says laughing. “Ever since we were married, we were always together—at the store, at the gift shop . . . always together.” But as the years got on, only she seemed to get older, and she left her husband to his summits.

Sam invited his children to join him, but they were busy with families of their own. In his grandchildren, however, he saw an opportunity to pass on what he’d learned in the mountains: Tradition, strength, and integrity were the touchstones in Sam’s life and central to his Korean identity. Hiking was the physical manifestation of all three. His eldest grandson Brandon was 6 when Sam first brought him to the top of Baldy. Three years later, when Sam brought Brandon to the top of Iron Mountain, they celebrated what Sam would refer to as “the indomitable spirit of Koreans.” Brandon wrote: “[These hikes] are the greatest gift my grandfather ever gave to me. He gave us a taste of that same happiness he felt.”

One year after Brandon’s first Mt. Baldy climb in 2010, his grandfather brought him back to the mountain, this time stopping to say hello to his friend Dick Tufts before their drive home. Tufts mentioned how many times he had been to the top of Baldy—more than 1,000—and gave Brandon an antique candy jar as a memento. His example inspired Sam to reach the milestone himself. Sam insisted that he, Dick, and Brandon sign and date the jar to commemorate the moment: “Dick Tufts Mt. Baldy Cabin; To Sam, Brandon; 1,000 times; 3-28-11.”

While it was a typically ambitious proclamation for Sam, David barely registered the significance when he later saw the candy jar in Brandon’s room. Sam and Sunny had only just finished their hiking project in South Korea; Sam had yet to begin his effort on Iron Mountain. Even those closest to Sam had no idea that he intended to follow through with this promise.

The San Gabriels are a hulking, 1,000-square-mile spine that runs east-west along the northern border of Los Angeles. Right where the city stops, the San Gabriels shoot up from near sea level to 10,000 feet, over just a dozen miles, with the peaks holding a thick frosting of snow for much of the winter. The range’s highest summit is properly known as Mt. San Antonio. But anyone who has been to—or even seen—its bare, wind-scoured summit hump knows it simply as Baldy.

The San Gabriels are so big, they can easily be seen from Sam’s home near the coast. But visible never means accessible in L.A. Each time he went to hike there, he would have to navigate a 60-mile stop-and-go labyrinth of concrete.

A single road snakes its way to the base of the mountain from the south, following a ravine that steepens and narrows as it climbs to the trailhead. First, it passes through the small mountain village of Mt. Baldy, then 5 miles later it dead-ends at Manker Flats. From there, the only way to continue is on foot. Giant lodgepole pines shade the gravel parking area and obscure views of the summits above.

It’s an unforgiving, nearly 4,000-foot ascent over 4.5 miles to the top. Beyond the map kiosk, the route starts out on a deceptively gentle fire road. Just 1 mile in, the steeper Ski Hut Trail zags away from the main Baldy Road trail and up toward the Sierra Club’s San Antonio Ski Hut. At the 80-year-old green cabin, the trees thin and the steep, scree-covered amphitheater of Baldy Bowl looms ahead.

Those who built the trail on the top third of the mountain didn’t waste any time trying to find the gentlest ascent. They just put their heads down and began chopping steps. Nearing the top, the gnarled, thinly spaced junipers look soaked in acid and the views stretch toward the sea in one direction and the desert in the other. It’s rock and dust underfoot for the final few hundred yards, until the pile of rocks that serves as a wind break beside the summit plaque.

It was here, on the summit, that Sam saved the life of Ethan Pontz. In late November 2016—the same year Sam climbed Baldy 250 times—Pontz and a friend were trying to sneak in an ascent before the summit was consumed by an approaching storm. Pontz and his climbing partner did in fact make it to the top. However, by the time they arrived, so had the weather. “Clouds engulfed us,” Pontz remembers. “Winds gusted over 40 mph and sleet pounded our faces. And it was so cold my phone battery died.”

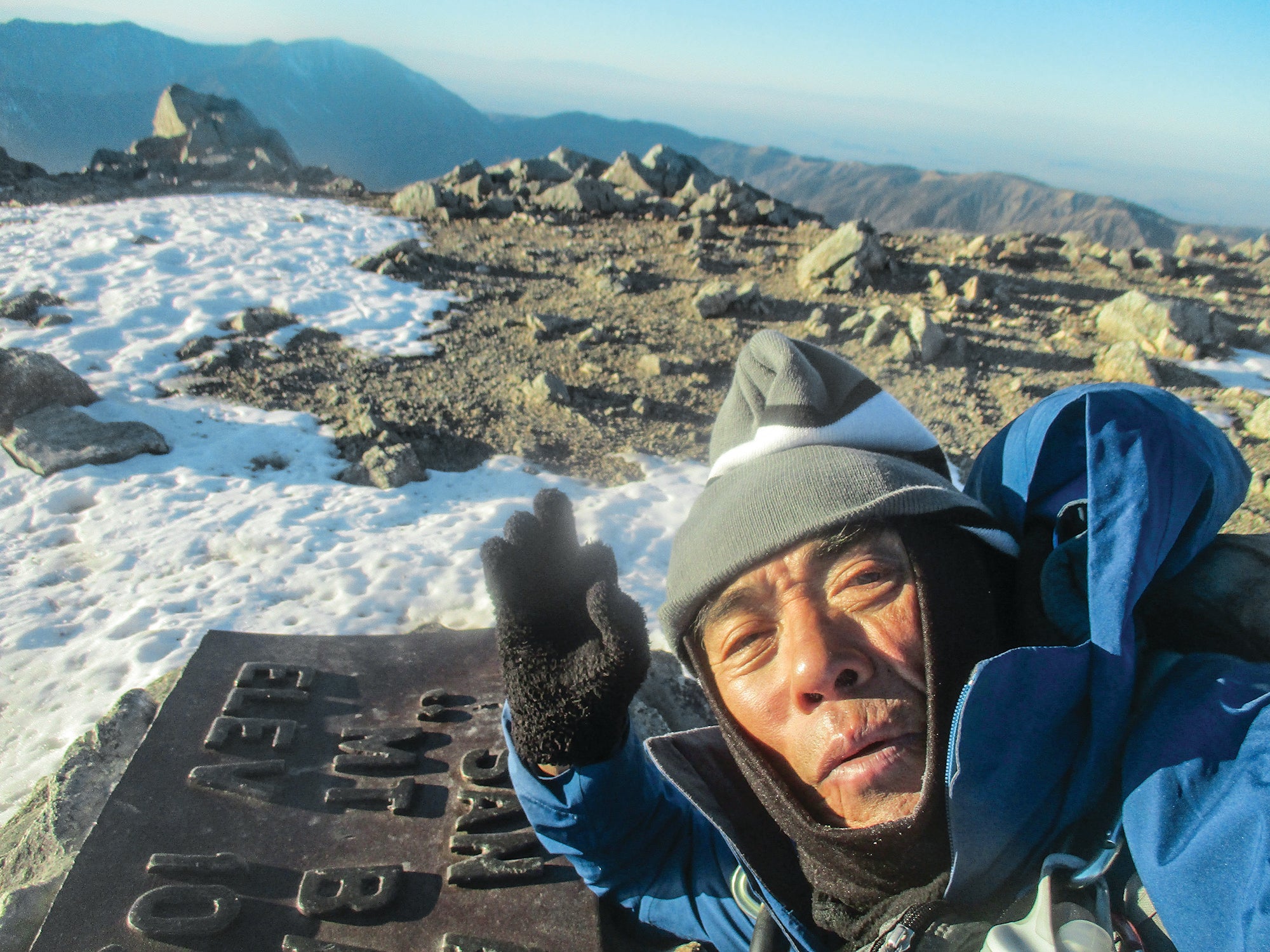

A few steps after starting down, just as Pontz was beginning to panic, he spotted Sam, who was on his way up. “His eyelashes were covered in snow,” Pontz says. “I asked him if he would guide us back down. He said he would, under one condition: that we return to the summit with him for a selfie”.

Once, when Deputy Richard Farrow of West Valley Search and Rescue was looking for four lost hikers who had gotten stuck high on the mountain after dark, he ran into Sam at 2 a.m. Farrow asked Sam if he had seen anyone on the mountain. “Sam tells me, in his broken English, ‘Don’t worry, they’re not injured, they’re just lazy,’” Farrow recalls. “Sam said he offered to lead them down to safety but that they wouldn’t follow him. The funny thing is that when they called and said they were lost, they also said there was some crazy guy up there.”

By the end of 2016, Sam had climbed Baldy more than 750 times. He was known to set off at all hours and in all conditions and his routine captivated other hikers. People started calling him the Spirit of Mt. Baldy. He first made the news for his accomplishments in 2014, when he and Sunny were featured in Mammoth Lakes’ local paper, The Sheet. In 2016, the L.A. Times ran a story titled: “Hiking Mt. Baldy? You’ll probably meet Sam, a 78-year-old Mountaineer.”

Later that same year, local CW affiliate KTLA aired a short segment about him. Not surprisingly, his legend was growing among the Southern California hiking community. Local bloggers posted about him and message boards lit up with Sam sightings. “Mr. Kim is amazing,” one commenter wrote. “It was my first time up Mt. Baldy and he encouraged me to push forward. He is the patron saint of the mountain.” One author on socalhiker.net said he ran into Sam half a dozen times on Baldy: “And every time I’d look at his infectious smile and think, Damn, this old guy is awesome.” Almost all of those he met recall Sam asking their names, ages, and if he could take a picture with them.

As for his family and friends, Sam’s quest was a lesson in acceptance. They had come to terms with the idea that his spiritual fulfillment far outweighed the physical risk.

In the spring of 2017, David was due to return from a family vacation in Europe and Sam was set on picking him and his family up at the airport. But because he didn’t want to miss any hiking, he climbed Baldy the previous day, slept in his car at the trailhead that night, then climbed it again the following morning before driving back to Los Angeles in time to greet his son.

Sam returned to Baldy again the following day, and, of course, the day after that. On the morning of Friday, April 7, 2017, Sam waited longer than usual for the freeways to thin out. He parked up at the Manker Flats trailhead that afternoon and set off up the Ski Hut Trail a couple hours before sunset, with clouds descending. Shortly after he began his hike, the weather turned ugly. “It was really bad, and by evening it was horrific,” Deputy Farrow recalls. “I lived in Claremont, at the bottom of Baldy Road, and if I can hear the storm outside my house, that means that at 10,000 feet it would be coming down hard: rain, snow, and whiteout conditions.”

Nevertheless, Sam had climbed Baldy in extreme conditions before, many times. Whatever he walked into that day wasn’t anything he hadn’t seen.

“I noticed it had rained that afternoon,” David says. “And I remember thinking about him that evening. I wasn’t worried, but I wondered if he was cold.”

David woke up the next morning to sunny skies in L.A. He called his mother to see if Sam had returned. He hadn’t. But, once again, David thought his father just had other plans that day. Or perhaps he had bunked down somewhere near the mountain, or slept in his car and was already headed up the mountain again. He always came home.

By late Saturday, there was still no word from Sam. David called his mother over and over, asking if she had heard from him. Finally, they both went to bed, fending off dueling emotions about Sam’s invincibility and his vulnerability. He was a solo hiker nearing his 80th birthday, but also someone who knew Baldy better than almost any other human on the planet.

“Even as I fell asleep, I still thought he would come home,” David says. “I could even picture him leaving again the next morning to do another hike.”

David woke up before sunrise and drove by his parents’ house. The moment he noticed the empty driveway, his heart sank. He immediately began driving toward Mt. Baldy. On the way, he phoned Dick Tufts to ask him if he could see his dad’s car in the parking area. Tufts confirmed that Sam’s white Land Cruiser was there. He also immediately laced up his running shoes, grabbed a backpack, and set off up the Ski Hut Trail with Bullet.

When David arrived in the village of Mt. Baldy that morning, he stopped at the visitor center to file a missing persons report. It landed on Deputy Farrow’s desk. “When we had to search for Sam, we weren’t just searching for an individual, we were searching for a friend,” he says. “I just couldn’t believe it.”

Sam had always tried to encourage his son David to hike more, but David, who is a physician, says he was never really an “outdoorsy” guy. Even his two young sons had been up Mt. Baldy more times than he had. That Sunday, however, David wanted nothing more than to climb Baldy to help search for his father. But the SAR crew insisted it would be safer for David to remain at the fire station. Instead, 30 or so trained volunteers fanned out toward the Sierra Club Ski Hut while David waited nearby for any word about his father.

The next morning, Sunny and her other son Kenneth arrived in Mt. Baldy Village. David and his younger brother were finally allowed to join the search, while their mother remained at the command post. As David and Kenneth made their way toward the top—for what would be David’s 15th ascent and Kenneth’s first—they shouted their father’s name and hoped for a miracle.

By Monday, more than 50 members of West Valley Search and Rescue were scouring the mountain looking for Sam, including a specially trained alpine unit. At 2 p.m. on Tuesday afternoon—a full four days after Sam set off up the trail—Deputy Farrow got a call on his radio saying that the helicopter had spotted a body, face down on the trailless north side of the mountain, about 2,000 feet below the summit. There was no mistaking the blue jacket.

Sam was found in a steep, rocky bowl, which would have been rimed in snow and ice the last day he climbed Baldy. “I honestly believe that when he began descending, he simply didn’t turn far enough,” Farrow says. “He lost his bearing, ended up just slipping and going down that chute.” The medical examiner suggested Sam likely died before his body came to rest.

Everyone from Sam’s family to Deputy Farrow are quick to point out one thing they are all certain of: Sam summited that day. At the time of his death at age 78, he had climbed Baldy more than 800 times and was on track to reach 1,000 by his 80th birthday.

But despite Sam’s own obsession with setting goals, numbers are not what defined him. Every climb mattered. That’s something those left behind take comfort in. They may never fully understand what drove him to the top of that mountain again and again, but Sam did.

Dick Tufts misses his friend but sees the poetry of Sam dying while doing what he loved. “I still feel like he is around me at times,” he says, “especially when I’m out there on the trail.”

Since his father’s death, David has hiked Mt. Baldy nine more times, and says he will continue to do so every Father’s Day. “It’s the ultimate tribute and it makes me feel closer to him,” he explains. “The cemetery where he is buried is only a couple miles from where I live, but when I go there it doesn’t seem like he’s there. He’s on Baldy.”

L.A.-based writer Will Cockrell climbed Mt. Baldy while reporting this story. It was his first summit.