How to Hike Mountains (Safely!) in Winter

'Christian Murillo'

5 Tips for Safe Winter Hiking

Winter hiking has a special allure but requires more vigilance than fair-weather outings. Weather, trail conditions, trailhead access, and wind forecasts all play into planning a day out in the cold weather. Having the correct cold-weather footwear, layers, and hydration is just the start. Here are five solid tips for winter hiking safety.

Know the Real Forecast

Local weather reports often predict conditions around the base of a peak, not the summit, but temps usually drop by about 5.4°F for every 1,000 vertical feet you gain. Antin uses Mountain-Forecast.com, which offers predictions for various elevations. Plan for the lows, not the highs, and check for both precip and wind speed. Consistent winds over 25 mph? Consider rescheduling.

Interpret Pre-Trip Weather

Antin starts checking the forecast for his objective at least a week in advance to get a sense of how much ice or snow he might be dealing with. (Rule of thumb: After two days at 50°F, you’ll lose 2 to 4 inches of snow, which could be the difference between snowshoes and bare boots.) And if you see subfreezing temps after a warm spell, expect ice. Depending on slope angle and mode of travel, you’ll want crampons, ski crampons, or mini spikes, and an ice axe for steep snow.

Stay on Track

Snow covers more than just trails—it can also bury cairns and other landmarks you might use to navigate. That means you’ll want some sort of GPS or nav app to supplement your map and compass. (Antin relies on his phone as his primary navigation and recommends the Gaia GPS app.) Keep your gadgets in a chest pocket of your base- or midlayer to preserve battery life.

Avoid Avalanche Terrain

Download Gaia’s Slope Overlay (premium subscription required) or use the same tool for pre-trip planning in CalTopo (free), and avoid hiking on or directly below yellow, orange, red, or blue slopes, which indicate angles between 30 and 50 degrees, on days with considerable to high avy danger.

Be Prepared to Be Alone

Solitude is great, but it means your group’s on your own if you get into trouble. Antin recommends traveling with at least one buddy and getting trained in first-aid (take a WFR course, or BACKPACKER’s online class). On more committing hikes, Antin carries a small shelter and a stove, just in case. “If you get stuck, daylight might be as many as 16 hours away,” he says.

Know When to Retreat

Does the terrain feel above your pay grade? Turn back. Insufficient food or water? Ditto. Frostbite is also a risk. Make sure you can feel and wiggle your toes, and for cold hands take this test: Touch your thumb to your index, middle, ring, and pinky fingers in that order to make sure you still have full motion in each. If not, call it.

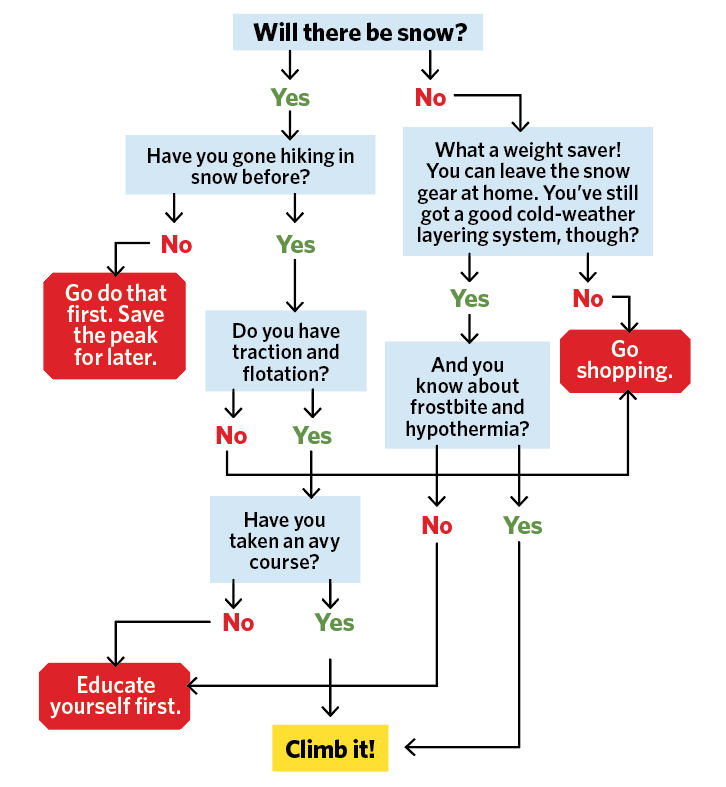

Should I Hike This Peak in Winter?

Before you pack up the car, do a gut check: Are you ready for this?

Assess Avalanche Risk

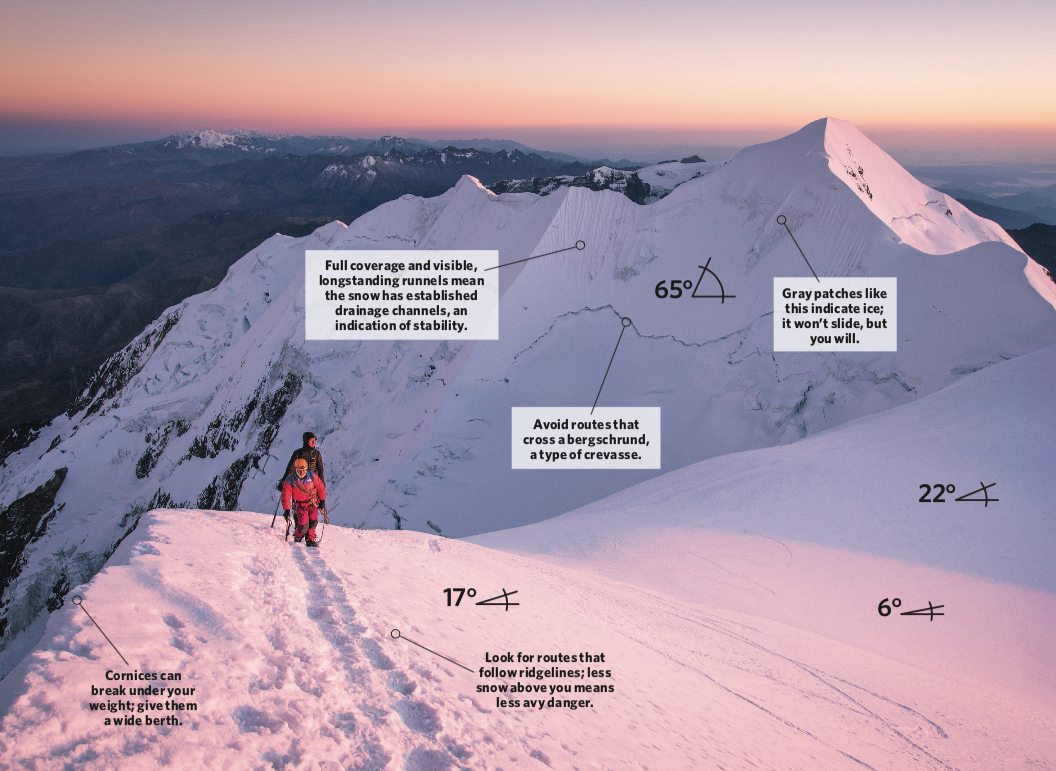

Pay attention before and during your hike to make sure you’re on solid snow.

Before hiking…

• Take a class. There’s no substitute for expert instruction.

• Check the avalanche forecast. Find your local report at avalanche.org. Note key factors, like certain areas, aspects, or elevations to avoid.

• Start early. Wet snow freezes at night, stabilizing it, but warmer afternoon temps can cause wet slides.

Factors to consider

Slope angle. Avalanches most often occur on slopes between 25 and 50 degrees, and dry avalanches, which are responsible for the majority of avalanche-related deaths, commonly at 37 to 38 degrees. Avoid hiking on or under those slopes.

Aspect. In the Northern Hemisphere, north-facing slopes receive less sun than south-facing slopes in winter. The snowpack on colder slopes is more likely to develop persistent weak layers, which inhibit stability.

Natural anchors. Snow on slopes with lots of visible trees and rocks is less likely to break loose as one piece. Only a few trees or rocks? Those signify a localized shallow spot, where the snowpack could be insufficiently anchored to the slope. Avoid these.

Slope shape. Snow stretched over undulating slopes, especially convex hillsides, is under more stress than straight or concave slopes, making avalanches more likely.

Red Flags

• “Whumpfing.” When a denser top layer of snow collapses onto a weaker layer beneath it, it creates a deep, reverberating “whumpf” sound.

• Shooting cracks. Stepping on unstable snow can cause it to crack and separate from the slope.

• Cornices. Wave-shaped heaps of snow at the apex of a ridge mean wind has deposited a heavy layer on the slopes beneath, making them likely to slide. Cornices can also snap off, triggering those slopes.

• Recent avalanche activity. Look for scraped hillsides with clumpy snow debris at the bottom. Clean, white blocks with sharp edges, and/or visible, giant snowballs mean the slide happened within days.

• Pinwheels. Rolling balls of snow portend wet slides.

It Happened to Me: Buried Alive

In December, 2013, 26-year-old pro skier Amie Engerbretson was completely buried by an avalanche near Alta, Utah. Her training saved her life. —Morgan McFall-Johnsen

I was in the worst possible spot when the snow started to slide. My buddy and I had set out that morning to ski fresh powder in Grizzly Gulch near the Alta Ski Area. We found a slope that was small and just beyond the Alta boundary—safe, I thought.

After a turn, I felt the earth shift, like someone had pulled a rug out from under me. Then my worst fear: The snow surface splintered beneath my skis. I was right in the middle of a releasing avalanche—and above a gully, where I’d surely be dumped and buried.

I immediately deployed my airbag and angled my tips toward a stand of trees, fighting to stay upright on the river of snow. I managed to grab a branch, but a second wall of snow pummeled me like an ocean wave, ripping the tree out of my hands and sending me cartwheeling. It took everything I had to keep my arm crooked in a protective V-shape over my mouth.

I landed on my back at the bottom of the ravine and had a split-second view of sky before the snow flooded over me, turning the world gray and silent and cementing me in place. It all happened in less than 30 seconds.

I knew I only had a few minutes of oxygen. I closed my eyes so I wouldn’t see the snow pressed against my goggles and repeated the same thought over and over: “Breathe slow. Stay calm.”

After about five minutes, I heard crunching above me. Then I felt a probe strike—they’d found me. The first thing rescuers uncovered was my right hand. Someone grabbed it and squeezed. I squeezed back and knew that I was going to live.