When an Alaskan River Trip Becomes a Journey Into Memory

'Louisa Albanese'

Is it 4 p.m.? Or maybe 8? As I traverse the moraine that leads back to camp, Alaska’s endless summer sunshine gives me chronological vertigo. To steady my mind I begin an audit of the day’s events: a bush plane ride past mile-high cliffs, packrafting across a glacial lake studded with icebergs, six grizzly sightings, one 30-foot leap into freezing water, one calving iceberg, a turquoise alpine lake, and (so far) three hours of “golden hour.”

It’s the first day of a paddling trip in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, on my first trip to Alaska. And the sunlight—19 hours of it a day in late June—isn’t the only thing I find disorienting. Even as grizzlies and icebergs and midnight sunsets come and go, I feel haunted. I know if ghosts exist, I’ll find my father’s here.

My dad was stationed in Anchorage when he served in the Air Force in the 1970s. As a child, I was unimpressed by his nostalgia for memories that struck me as absurdly grim, like spending months of darkness and isolation in a cabin with doors on each of the four walls because of the likelihood that three might become inoperable due to snowdrifts. Whenever his temper flared, which was often—over anything from politics to the car not starting—he’d declare, “I think it’s time to move back to Alaska.” I took this statement as a personal threat. On more than one occasion, it left me in tears. When you grow up making regular trips to visit extended family in the Caribbean, the idea that anyone might prefer a barren, snow-covered hellscape to warm, sugary sand is beyond comprehension.

My dad died a few years ago, and like many losses, this one left me with questions and regrets. Our relationship had been tense and complicated. My sisters insisted that we clashed because we were so similar, but I refused to believe we were anything but opposites. The only thing we shared was a zeal for adventure, but even that, he’d turn into a competition. Whatever I set my mind to, he’d done it better, farther, with more pizazz.

As a young adult, I went rock climbing for the first time. When I started to tell him about it, he interrupted with a story about his own ascents of Yosemite’s granite. I couldn’t mention the time I’d spent trekking in Guatemala without my dad recollecting the jungles of Vietnam. At best, these exchanges annoyed me. At worst, we argued until we stopped speaking.

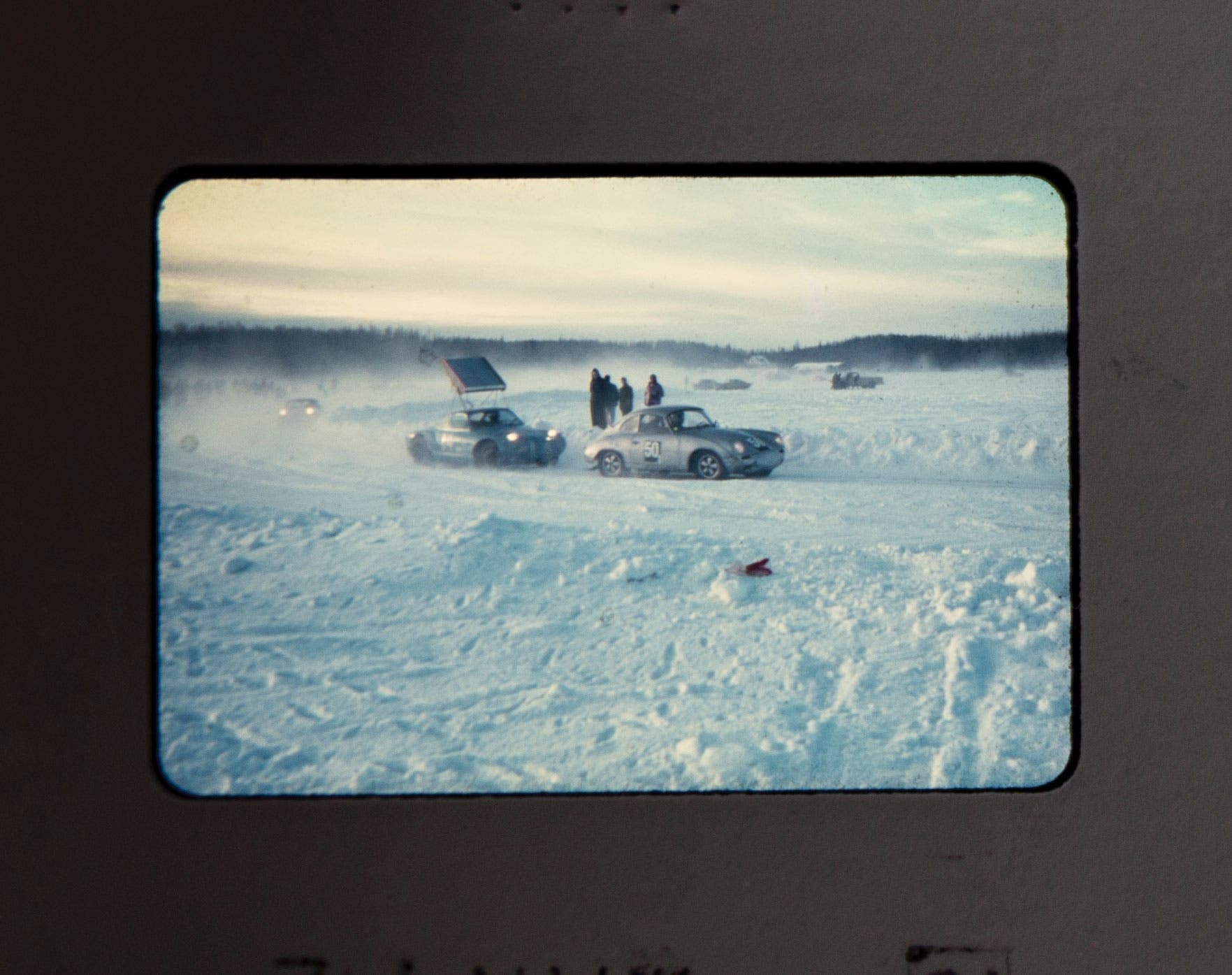

Somewhere along the way, I began to suspect his stories were exaggerated truths or even shameless fiction. A detective, a decorated war hero, a helicopter engineer, a motorcycle-riding competitive sharp shooter who would race his Fiat on the frozen lakes of Alaska—how could all these things describe the man I’d grown up with? The dad I knew shoveled coal for a living, never finished college, and was overweight and out of shape. By the time I was 20, the idea of him climbing in Yosemite began to seem as fanciful to me as if he’d claimed to have wrestled an Alaskan grizzly.

In early June last summer, as I was rummaging through some boxes in my garage, I found an envelope marked with his familiar, perfect penmanship: “Alaska.” It was full of slides. I carefully held up picture after picture to the fluorescent lighting and recognized a boyish version of my father smiling beside a snow-covered cabin, and images of cars racing on ice. Hot shame prickled my neck, and I could hardly see through my sudden tears as I slumped to the concrete floor. Where had these slides been during my childhood? I longed to confess to him that I’d been wrong, to ask for forgiveness. But it was too late for that. Instead, I hung the slides in my office—an act of contrition.

But fate would not be satisfied with my silent offering. The day after I discovered the slides, I was invited to go packrafting in the Last Frontier. In my mind, I could see my dad grinning at the irony. Despite my lifelong resistance to going anywhere cold, I understood that I owed my dad this belated act of allegiance.

After an eight-hour drive east from Anchorage, our group of 10 arrived in McCarthy, the historic mining-era town that now serves as the gateway to Wrangell-St. Elias. It was the end of June, and the weather was sunny and 70°F—a soft landing by Alaska standards.

We spent two days in McCarthy learning the basics of whitewater packrafting before our three-day, 45-mile trip in Alaska’s largest national park. Our plan: paddle across Nizina Lake to connect with the Nizina River, then navigate the class III rapids through the heart of the Wrangell Range.

But Alaska has a way of making you second guess even the most well-planned trips. Standing on the edge of the black waters of Nizina Lake as our bush plane buzzed away, I felt doubt seep into the pit of my stomach. We were now deep in the Alaskan wilderness, where the consequences of any error would be magnified. Was I in over my head, trying yet again to outdo my dad?

That morning, we paddled for two hours through a quiet as pervasive as the silence in a cathedral. The lake was a maze of icebergs, and for lunch, we stopped to explore one on foot. The ’berg was bigger than a luxury yacht, and it concealed a perfectly circular cave, the thinning ice reflecting a brilliant blue bowl. Nearby, we found a 30-foot cliff above the frigid water, and others started jumping in. The leap was way out of my comfort zone, but I could feel my dad looking on and knew I had to do it. Plunging beneath the surface was a shock—even in a dry suit you feel the cold. The baptism in glacial water reminded me that I wasn’t here to compete; I was here to surrender.

After another two hours on the water, we pulled ashore and made camp a few hundred feet from the rocky beach. We’d barely finished setting up when one of the guides calmly mentioned that we “had a visitor.” A lone male grizzly was marching along a ridge 500 yards away. Even at this distance his size was impressive, and he paced back and forth as if to make sure we knew whose turf we were on. Then a biting crack broke the stillness and a hunk of ice the size of a school bus fell from the glacier two football fields away. A spontaneous cheer rose from the beach. “Alaska is really showing off for you guys!” our guide laughed. Nope, I thought, this wasn’t Alaska’s doing. This was my dad.

Or maybe I was giving his ghostly presence too much power. I drifted away from the group to think, which is when I get confused about the time. Is it 4 p.m. or 8 p.m.? It’s actually close to 9.

Seeing Alaska in all its wild reality, I realize that my dad’s descriptions were actually modest—there’s no exaggerating this place. Maybe he wasn’t showboating—Alaska just made a big impression on him. Maybe he’d only wanted my admiration, my approval, or just my love. These kinds of questions began moments after he died. Before I’d even left the hospital parking lot, my mind, as if acting on its own, began to pardon each injustice. Was my dad really as difficult as I remember? I realize I need to let go of the uncertainty, just like I need to give up checking the unreliable numbers on the clock.

That night, a single lonely star appears in the semi-darkness. For hours, fragments of ice the size of three-story buildings fracture from the glacier as if detonated. They splash into the water and send 3-foot-tall waves crashing onto the beach. Ice chunks the size of boulders wash up all around us, and we run between them, squealing like kids at summer camp. It’s 2 a.m. before the ice show quiets, and no one is the least bit tired—another gift from Alaska.

The next day, we paddle down a braided, silt-filled river, ready for anything. The sound of the water splashing against my boat provides a soothing rhythm, and my thoughts bubble along like the waves.

In a way, both my dad and I were right about Alaska. It’s as captivating as it is unforgiving. But it’s also the gift he always tried to convey: His stories were never meant as a challenge, but an invitation. There in my boat, heading into the wildest country I’ve ever been, I cry. I cry for myself, knowing I’ll never get to tell him that I finally traveled here. I cry for him, that it took his daughter 35 years to see him as he truly was. And I cry for my own two kids, who will now have to endure my own tales of magical Alaska.

Do It

Getting there Fly into Anchorage and drive or shuttle to McCarthy. Season June to August Permit None Route The Nizina River is referred to by the National Park Service as a “class III river with class V consequences.” Expert paddlers can do this route DIY (go to backpacker.com/nizina for details), but a guide is highly recommended. Guide Kennicott Wilderness Guides ($1,600/person for a group of four for a three-day trip, includes bush plane flights and all gear)