The Trail to Neverland: Hut Keepers of the White Mountains

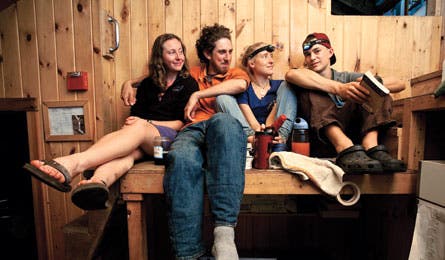

'AMC hut caretakers (from left) Elizabeth Waste, david kaplan, Chelsea Alsofrom, and Luke Teschner. '

AMC hut caretakers (from left) Elizabeth Waste, david kaplan, Chelsea Alsofrom, and Luke Teschner.

hut staffers often serve dinner to more than 30 hikers a night.

Galehead hut was rebuilt in 2000.

Cooking duty rotates between hut workers.

The kitchen crew bakes fresh bread daily, from scratch

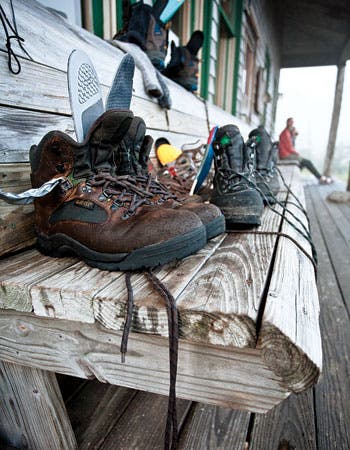

Boots dry outside the hut.

taffers Alsofrom, Siner, teschner, and waste sing a dixie chicks tune to let guests know itâs time for the communal meal.

There’s something hallowed-looking about the faces of people the moment they step through the door of Galehead Hut, 3,800 feet up in the White Mountains of northern New Hampshire. They’ve arrived there, invariably, on foot, over steep, rock-rubbly trails dotted with lichen-specked cairns and roots and stubby, wind-stunted evergreens. And they’ve traveled, often, up through cold mountain air and wisps of fog and lashing outbursts of rain.

By the time they reach Galehead–a rustic hikers’ bunkhouse and mess hall 4.6 miles from the nearest road–they are weary. But they’re also sort of floating, for they have wriggled free of the niggling abstractions of everyday life and accomplished something solid. They’ve traveled here on their feet. Their boots are dirty and their faces glisten with sweat, and they’re somehow alight with such pure happiness that, watching, you think, “That person is good.”

Whenever someone stumbles through Galehead’s front door at dinnertime, two dozen or so people at the long dining tables cheer–the applause is instinctive. Indeed, sometimes when you are merely waiting for someone to show up at Galehead, a certain aura of celebrity builds up around him, particularly if the new arrival has ever served on the hospitality staff–or the “croo”–in any of the eight shelters of the Appalachian Mountain Club’s White Mountains hut system, which was established in 1888.

Croo workers are almost invariably college students or recent grads, and by some measures they’re simply $7.25-an-hour wage slaves in a backwater of the tourism industry. The 49 caretakers who labor in the Whites’ huts every summer are tasked with cooking guests’ meals, selling them souvenir water bottles, and, every few days, wielding a stick, so as to stir the huts’ composting toilets. But their real mission is spiritual. It’s their charge to keep alive the delight that imbues each hut arrival, even after the dining hall starts festering with the fetid scent of wet, blister-bloody wool socks.

Hut workers sing and play guitar. They perform skits. And carrying 50-pound loads of food for the guests, they bound up mountain paths with lightning grace. Often, they become legends within the tight croo community–and on a chill, gray afternoon at Galehead last June, the hut’s five resident caretakers gather in the large, airy kitchen and await the arrival of two such legends: Gates Sanford and Alex May. Both are hut alumni, and collectively they’ve served seven seasons in the White Mountains.

“Alex May is coming?” one staffer says. “No way.”

“Yes, Alex May,” says his colleague, with a hushed reverence. “Alex May. And Gates too.”

I’m familiar with this sort of reverence, for 30-odd years ago, when I was a scrawny grade-schooler hiking hut-to-hut through the White Mountains with my mother and sister, I regarded the hut workers as looming gods–as lords over a surreal alpine kingdom where you could actually have snowball fights in July. More recently, as I’ve aged, I’ve wondered how a bunch of college students (children, essentially, from my antique perspective) could possibly run the nation’s oldest network of mountain shelters. The responsibilities are ominous. Hut staffers double as search-and-rescue crews, and they function as lifeguards to the myriad unprepared hikers who shamble up some of the nation’s most punishing trails. The White Mountains are steep, and devoid of switchbacks. There are frequent summer hailstorms and the wind can gust to more than 200 miles per hour. Since 1849, more than 130 people have died on the slopes of the Whites’ highest peak, Mt. Washington.

The threats are real, to be sure. But for the most part these young adults spend their transformative years working like glorified counselors in an extended version of summer camp. Does that mean they’re growing up fast, or not at all?

When Sanford and May step into galehead hut, they’re bare-chested–never mind the dank cold. They are cut, both of them, bearing nary an ounce of body fat, and upon seeing them, a couple of young women begin shrieking–literally screaming, so the shrill sound ricochets about the whole wood-shingled hut, over all 38 beds in the four bunk rooms. One admirer, a visiting emeritus hut worker named Emily Taylor, finally exclaims, “I’m overwhelmed right now–there are so many people I love right here in this room.”

Sanford, 26, begins clomping around the kitchen with a proprietary air. “When I was working here,” he says, alluding to a recent autumn, “our compost was on fire. It was 157 F degrees in October! And we didn’t use cookbooks. Are you kidding me? We freestyled shit. On the chocolate cake, we tripled the baking chocolate and cut the cooking time in half.”

Sanford declaims to all present, like a Shakespearean character strutting the boards of the stage, but his soliloquy is directed mostly at one young man. Luke Teschner, a 20-year-old croo rookie whose father worked in the huts in the 1970s, is single-handedly cooking dinner for the 20 guests at Galehead tonight. Teschner is a lanky and well-mannered kid, soft-spoken and humble. He sports a blonde crew cut and a neat black earring in his left ear, and earlier he confided that he’s a bit freaked out by the whole culinary thing. “Before this summer,” he says, “I never cooked anything. I mean, like nothing. At school, I go to the dining hall. But the recipe book they have here? It’s awesome! You follow the instructions–this much sugar, that much flour–and it works. It’s cool!”

Teschner ignores the cookbook now, though, as he bends over an index card headed “Mom’s Vegetarian Chili.” The card is handwritten in red Magic Marker, with a little heart drawn up in the corner. Nearby, on the stove, there are three pans of fresh herb bread still warm from the oven. Sanford steps toward them with a knife.

“Actually,” Teschner says, “I only made enough for…”

But before he can finish, Sanford rips off a heel slice and starts chomping. “Dude,” he calls out to his friend Alex May. “There’s some knockout herb bread here. Get involved!”

Within 10 minutes, a full loaf is history. And all Luke Teschner can do is stand there and glower and hope that this chili dinner–the second meal he has ever cooked in his life–will come off OK.

It’s not easy getting a job on croo. This year, more than 130 people applied for 20 open positions. And the appeal of the work is not immediately obvious. There you are, up in the mountains, cut off from all frontcountry pleasures–Facebook, school buds, beach parties, whatever–and obliged (at least at Galehead) to live for 10 weeks in a cramped 10-foot-by-10-foot bunk room with four other staff, each of whom often goes more than a week without bathing. (Croo members work 11 days on, three days off.) The social scene can get confining and testy.

Still, life is delightfully slow-paced. Workers help out with breakfast and dinner, and typically have afternoons off. In their free time, they’ll spend hours handwriting letters to friends, or updating journals, or enjoying picnics on mountaintops. They hike almost daily, and on my first stay at Galehead, Nick Anderson decides to bust out and climb a trail that scales 1,100 feet–ascending South Twin Mountain in less than a mile.

Anderson, 21, is Galehead’s assistant hutmaster, and a rather serious youth who often wears a pin-striped, blue-and-white oxford shirt while interacting with guests. (“You look fantastic,” Sanford tells him, “straight out of the summer Polo catalog.”) Short and sturdy, with curly black hair and a frequent black stubble on his chin, he does look quite dashing. He’s a fast hiker, too. Once, he made it to Greenleaf Hut–7.7 miles away, and over two mountains and through a trickling, sole-soaking cascade–in a blazing two hours and 45 minutes. Still, I invite myself along on his afternoon jaunt.

“OK,” says Anderson.

I follow. He lollygags for the first 50 feet or so and then, with no preamble, he turns his stride into a leap and begins hurling himself up the mountain, knee to chest, knee to chest. I’m in decent shape; I keep up. But I move with a desperate and gasping intent, gritting my teeth against twinges of pain in my knees, and Anderson just flows up the hill, chitchatting, oblivious to how lucky he is to possess fresh, unblemished cartilage.

Anderson is light on his feet, at all times. One night, when 10 little girls come to the hut with their parents, he summons them all to a table after dinner, leans toward them, and, in hushed, spooky tones, tells them ghost stories. The girls all giggle and squeal–and then, afterward, they linger about him, burbling, as though he is the drummer for the Jonas Brothers.

Working in the huts, it strikes me, is kind of like being in Neverland: You can stay on only as long as you remain young, unburdened by the worry and self-consciousness that crust on over time. And as with any fairy-tale landscape, arcane mores apply. Every summer, for instance, hut workers seek to distinguish themselves by “packing a century”–that is, by lugging a full 100 pounds into a hut, usually with a plain wooden packboard. But the most critical ritual is the raid. Half seriously, half in jest, the croo of one hut will invade another hut, sometimes “stealth raiding” at night and sometimes executing daytime “power raids” replete with all the sinewy horseplay of professional wrestling: chokeholds, half-nelsons, full-body pins. The object, always, is to steal previously heisted detritus attached to the walls of the invaded dining room: old road signs, for instance, and antique skis.

The practice of raiding began soon after the first AMC hut opened in 1888. In the 1940s and ’50s, the prize booty was a human skull, “Daid Haid,” lifted from an abandoned logging camp. Later, in more politic times, an airplane propeller, recovered from a high-mountain crash, was coveted above all else. Today, the grail is a long wooden rowing oar that was used, allegedly, in the 1972 Olympic Games. As the summer begins, the oar is at Zealand Falls Hut. The croo at every other hut wants it. “Once you have the oar,” Galehead staffer Chelsea Alsofrom, 22, tells me, “you don’t really need anything else.” Raid strategies and other clandestine plans are often hatched in the privacy of the kitchen, away from the guests. There, after dinner one night, Sanford unveils a plastic liter jug of Canadian Hunter whisky, along with a T-shirt that features his name (Gates “Rolling Thunder” Sanford) and the slogan “Get Hunted.” In Sanford’s day, Canadian Hunter was so celebrated among croos that one hut worker, a burly, mustachioed youth, was known simply as “The Canadian Hunter.”

“This stuff is vile, by the way,” Sanford says. “We did a taste test between it and Old Crow, and Old Crow won.”

It’s quite possible that Sanford could afford a tonier brand. He prepped at Milton Academy, and his grandmother owns a house in the Hamptons. Which shouldn’t be surprising. The huts have always attracted well-to-do Easterners. The first staffs were heavily represented by Dartmouth and Harvard, and today the huts still offer up-and-comers a chance to fly free of expectations–to get muddy and loopy up in the mountains.

The bottle goes round. No one gets anywhere near wasted. But toward the end of the night, Teschner wears a warm grin. “I’m feeling,” he says, “a little Canadian poached.”

The next time I visit Galehead, in early July, Teschner is off-duty, at home in Haverhill, New Hampshire. Anderson is hanging out in the kitchen. I’m a little hesitant to go in there, though. The kitchen is the one refuge where the croo doesn’t have to be all cheery and customer servicey, and sometimes when a guest peeks his head in there (to ask for tea water, say), it’s as though he’s crossed an electrified line. Anderson has been working for more than a week straight. Still, I decide to venture into the kitchen, where he’s reading a book. “Yeah?” he asks. I begin awkwardly, asking if being up in the mountains is losing its luster now, midsummer.

“No,” Anderson says. “I mean, has your life suddenly become less exciting for you because you were alive last year?”

I kind of move my jaw for a second, without speaking, and then I retreat to the dining room, intrigued. All along, I’ve been looking for little explosions–for telling failures in the Galehead machine. But I’ve seen very few, and minor ones at that. One morning, Sanford repeats the name of some woman and Anderson storms out of the room, irked. After another morning’s breakfast rush, Chelsea Alsofrom is supposed to tidy the bunk rooms. When she blows it off, the hutmaster, 22-year-old Katherine Siner, rolls her eyes and says, “Having this job is like being a mom. Someone has to be responsible.”

But mostly the hut glows with authentic, transcendent joy. On Bastille Day, 11 older women–one-time Girl Scout leaders who call their group “Babes in the Woods”–rise from the table and sing “La Marseillaise” before packing up and leaving a generous tip. (“We’re mothers,” explains the Babes’ leader, a lawyer. “We’re happy to know that there are young people up here, levitating over the trails.”)

The croo never imposes themselves on anyone’s holiday, but they sprinkle the festivities with good cheer of their own. “Hi, I’m Luke,” Teschner says one night during the staff’s standard after-dinner spiel, “and one interesting fact about me is that I’ve gone skiing in Africa. It’s a true story.”

“Hi, I’m Nick,” Anderson says, “and today, hiking, I stepped over a dead moose.”

It’s their job, of course, to be cheery, and they pull it off 99 percent of the time. Indeed, one night when I sit down with Siner, the hutmaster, she speaks in relentlessly upbeat tones. “I’ve learned so much in this job,” she says, “about responsibility, about working with other people, about guest services.”

I never would have talked like that in college. I would have been skulking in my bunk, reading Nietzsche as I silently fumed over the Orwellian implications of the huts’ communal dining scheme. Or, more likely, my application would have been nixed. The AMC is careful and somewhat image-conscious in its management of the huts. The club’s publicist specifically routed both me and another reporter toward Siner. He enjoined me from going on a raid, and before my first hike into Galehead, he met me at the trailhead and gently pleaded for sympathy. “If they say anything crazy,” he said of the staff, “remember: They’re young.”

The publicist didn’t hike in with me, though, and the AMC never sent any busybody, iPhone-toting “hospitality specialist” up to Galehead to ride herd on the crew. The graying administrators seem to recognize that the huts’ magic lies in surrendering control to the kids. The whole show is like a mountain flower in springtime–you don’t want to mess with its loveliness.

One morning at 6:30, Siner and another hut worker, Elizabeth Waste, stand in the hall outside the bunk rooms, silhouetted in the soft gray light coming in the fogged-over window, and play a wake-up song, “Angel from Montgomery.” The folk classic is a sad and plaintive tune, a story told in the voice of an old woman at the end of her life. “Just give me one thing that I can hold on to,” it goes. “To believe in this living is just a hard way to go.”

The two young women sing softly and with tentative care, Siner holding the lyrics out before them. And as the guests begin traipsing out of their bunks (silent, unshaven, stooped and pottering about, in old long johns speckled with odd scraps of bark), I am moved to reflect that people have been waking like this, to the sound of the human voice, in the AMC’s huts for more than 120 years. The whole virtuous endeavor of sallying forth into the fresh air of New England’s high mountain climes began back when men hiked in knickers and women in long woolen dresses, and it is still going on. Kids are still playing mandolin and singing up in the mountains with sweet and earnest intent–it’s one thing to hold on to.

“We’ll have breakfast for you at 7,” Siner says, wrapping up. The salt smell of sizzling bacon wafts out of the kitchen, and the guests gather their toothbrushes and limp along toward the bathroom and its cold-water taps.

By midsummer, the croo settles into a veteran rhythm. Teschner starts reading a history book on Iran. He sets an easel up in the hut’s storage loft and begins painting the sylvan view from the window. Meanwhile, speculation mounts as to which hut will end the summer with the oar. Commonsense favors Lakes of the Clouds, the biggest hut, with 10 workers; Lonesome Lake, very small and remote, is a dark horse. But then Galehead bursts into dominance in late July, during a complex series of battles. To do it all justice, I’d need to conjure a hoary military historian with a wooden pointer, gesturing at a roll-down map.

In brief: One morning, on the short-wave radio, Anderson overheard that two croos were conspiring to converge on Zealand, to seize the oar. The invaders’ huts would, of course, be understaffed, so the Galeheaders split up and power-raided both of them, garnering an oversized wooden spoon and a few dilapidated signs. The oar ended up at Greenleaf, and one afternoon Anderson and Alsofrom hiked there, timing their arrival for lunchtime, when only one staffer was present. Anderson wore a skirt for the occasion. He and Alsofrom pinned their foe to the floor. “She fought like hell,” Anderson says. “She squeezed Chelsea’s head in a door pretty hard, and she kept kneeing me.” A crowd of hikers gathered. “People were videotaping us,” says Alsofrom.

After Anderson wrenched the oar from the wall, he gave it to Alsofrom and together they rushed it three miles downhill, to a parking lot, where Teschner was waiting with a getaway car. The next day, the croo of another hut, Lonesome Lake, raided Galehead, led by a large and swashbuckling red-bearded young man whom Teschner calls “the Jack Black of the hut system.” Johannes Griesshammer, 21, pried through a rope lashing Galehead’s front door shut and shouted, “Let the onslaught begin!”

But Galehead had been tipped off, and the staff had hidden the oar in the woods atop measly Galehead Mountain. Is this legal?

“Semi-legal,” Alsofrom tells me, days later, still gloating. “We’re like monsters. We steal and then we lie. It’s awesome.”

When I go back to the Whites, it’s a bright, warm day in early August, and I meet Teschner at the Gale River trailhead. He’s on a mission. He’s hiking up Galehead Mountain to retrieve the hidden oar. “I just ate a whole pint of Ben & Jerry’s,” he says, walking toward me. “Let’s see how that goes.”

We start walking. Teschner’s hair is a little longer now, less bristly, and he has patches of duct tape stuck on his shoulders, covering an oozing yellow melange of friction sores. Two days earlier, he had packed his first century, laboring up the Gale River Trail bearing 110 pounds. “When I first came here,” he says, “I thought carrying 50 pounds up the trail time after time was going to crush me. I didn’t see how I could do it. But I broke the trail down mentally, into sections–this river crossing, that rocky pitch. During the last quarter-mile, I felt like I was going to collapse. I could hardly put one foot in front of the other, I was so tired. But I never questioned that I was going to make it. I’ve gained confidence this summer.”

I ask what he means. “Well,” he says, “I’ve definitely become a better cook. I’ve made peanut butter bars and apple spice cake; the other night, I cooked pasta primavera. I’m thinking about opening my own restaurant some day.” The scheme is vague. He says something about a “tiki bar in the U.S. Virgin Islands” and then adds, “I still think the cookbook is awesome.”

“Oh,” I say. I guess I’d hoped for deep insights–for dispatches from a mind finding its way toward cool adult poise. But the process of growing up is subtle and incremental, and Teschner is still ensconced in the woods of it. He cannot offer up any sweeping perspectives.

We cut across the river. Teschner stoops low to a cold pool of water and says, “Usually when I get here, I dunk my head in. It’s refreshing. The way you do it is you put your hands on these two rocks here, like you’re doing a push-up, and then you kind of lower…” He goes underwater and then he pulls his head out and shakes it, so the water flies off the tips of his hair. Then he waits as I dunk my head into the icy river.

When we get up on Galehead Mountain, the sun shines brightly and the oar is fairly visible in a thicket of trees. The wood on it is a little chewed up, and its metal paddles are bent, but the grail is now solely in Luke Teschner’s care. He isn’t giddy about it, but he does seem quite pleased. “Here we are in the middle of the woods,” he says, “and there’s stealth treasure lying around.” He shoulders the oar, which is surprisingly light, and starts down the tree-lined trail, carefully. The oar has a wide turning radius.

When Teschner reaches the hut, he fetches a long ladder and leans it against the dining-room wall. He climbs it and then pounds in some nails up near the ceiling, for the oar to sit on. Anderson stands at the base, holding the ladder and giving instructions: “Yeah, another nail there. Good, good.” Teschner bends the nails tight around the oar handle. He balances a cache of butter knives on a thin ledge above, so that a cascade of cutlery will rain down on any would-be marauders. And then he sets a large sign–“Dog Walk,” it reads–dangling below so it will fall like a guillotine if the oar ever is touched. “Ah yes,” Anderson says, peering up. “This is evil!”

By my reckoning, Galehead is toast: It’s only a matter of time, it seems, before invaders will come along to deliver the Galeheaders a large serving of humble pie. Indeed, one day over lunch, Johannes Griesshammer, aka Jack Black, pronounces ominously that he will blitz for the oar “in the very near future.”

I wait. But as August wears on, the thrill of raiding–and being up in the magical huts–finally wears thin. “It takes a lot of social energy being here,” Alsofrom says. “It can only last so many weeks and then you want summer to end.”

On August 20, with the oar still up on the wall at Galehead, the summer croos come down out of the mountains. Life as the rest of us know it resumes. Autumn arrives, eventually, and myself, I keep thinking about the sublime, long-ago joy of being up in the Whites amid blinding patches of snow as the summer sun baked down upon my bony little kid back. I begin hatching this theory that the most important part of the whole hut experience involves remembering the place and wanting to go back. And that’s when I think of Emily Taylor, the hut veteran who visited Galehead on my first night there.

Taylor is 24, and a small wire of a person, black-haired, tiny, and tautly muscular, with this intense, bouncy ebullience about her. She came to Galehead straight from her job at an organic farm in Portland, Maine, driving three hours right after work and then beginning her hike in at 7:30 p.m., bearing a six-pack of beer.

“I’m so happy to be here,” Taylor said, arriving, “so happy.” But she told a wistful story about her previous summer, her sixth and last season in the huts. It came right after her graduation from college. She was the hutmaster at Carter Notch, and Chelsea Alsofrom was on her crew. “I have so many great memories,” she said. “When it rained, I’d sit on the kitchen floor on a blanket with Chelsea and listen to James Taylor on an iPod. But I was stressed out, running a hut, not knowing what I was going to do in the fall.”

“You saved your senior spring college freak-out for the hut,” Alsofrom said. “It felt like you were having an existential crisis.”

“I was just feeling,” Taylor said, “like I couldn’t do another summer. A goal of my life had been completed, and I felt like I was being torn out by the roots.

“I wish I still had the energy for this job,” Taylor continued. “I wish that I was still OK with sharing my home space and that I could set out silverware again, without feeling like I was going to scream. I wish I could go back to being 19. I loved the huts; I’ve felt so at home here. But it’s time to move on.”

Luke Teschner was lingering by the stove as Taylor reckoned with the hard reality of growing a little older, of no longer belonging where once she was so comfortable. Does the sting of her story register on him?

He doesn’t remember, he says when I call him this spring. But he is looking forward to going back to the huts in June. He’ll be at Madison this time. “I’m pretty excited,” he says. “Madison is the oldest hut in the system. It’s above treeline. It’s notoriously the hardest hut to get to. The hike in is steep, so you tend to get more hardcores there: people who really know what they’re doing. It’ll be good. It’s gonna be a good summer.”

Bill Donahue lives in Portland, Oregon. He wrote about that city’s Forest Park for the October 2009 issue.