The Onion vs. Mr. Magoo

'Francis \"Mr. Magoo\" Tapon'

Francis “Mr. Magoo” Tapon

Garret “Onion” Christensen

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

onion vs. magoo

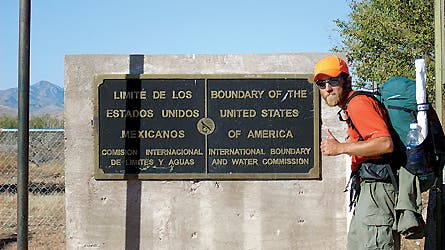

ON A WARM NEW MEXICO MORNING last fall, Garret “the Onion” Christensen pulled up his socks, threw his green ULA Equipment pack onto his back, and prepared for a bizarrely long and arduous sprint. In front of him lay gravelly County Road 603, and beyond that half a state’s worth of rough hiking, including high-desert bushwhacking, countless river crossings, and the punishing Gila Wilderness. Formidable stuff for just about anyone else. But the Onion, an ultra-distance backpacker who measures his treks in the thousands of miles, knew he’d hit this journey’s homestretch. Good thing, given what was at stake. Without a minute to lose, he tugged on the brim of his blaze-orange baseball cap, faced south, and broke into a businesslike, three-mile-per-hour walk.

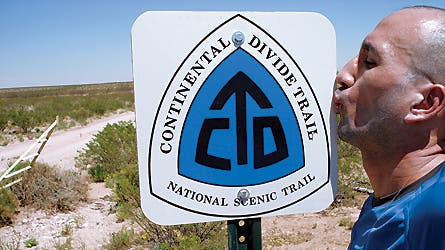

The Onion, who had years earlier nicknamed himself after the satirical newspaper, had reason to believe that he could become the first person to complete a roundtrip hike of the Continental Divide Trail. The attempt was over the top: a 5,600-mile journey, north from the bottom of New Mexico, following a tortuous path to the top of Montana–and then back again. But vast distances, snow-choked passes, and a labyrinth of trails weren’t the only obstacles between the Onion and the record. Another guy was simultaneously attempting the same epic trek. Francis “Mr. Magoo” Tapon was also in New Mexico, ahead of the Onion but still 150 miles short of the finish. The 37-year-old Magoo was a strong hiker, too, and yet over the previous five months he’d consistently lost ground to the trail-Hoovering, 28-year-old Christensen. The face-off was crazy enough to be worthy of a story in The Onion itself. One could imagine the spinny headline: “Magoo Dices Onion at Border!”

The pair’s final kick was made doubly weird by the fact that hiking–of any distance–is generally the least competitive of sports. Indeed, when the Onion and Magoo briefly met before starting their journeys, the two men had agreed that they might ultimately walk together. Share the trail and the glory, as it were. But that was many miles ago, and now the end was enticingly close. Put yourself in their boots: Come within a couple of hundred miles or so of being the first to do the whole shebang twice, without stopping, and who wouldn’t have winning on one’s mind?

“Though you started 25 days after Francis, the current projection shows you returning to the Mexican border only three days after him,” a scorekeeping friend had written in a goading email to the Onion. “You kick ass!”

Mr. Magoo, meanwhile, was leaving the impression that he was staggering to the finish. “I figure that the earliest I could get there [the U.S.-Mexico border] is October 31,” he wrote in an email to the Onion during the hike’s later stages, at a time when the Onion believed that he himself could finish around October 30. “Daylight is vanishing ….”

Thus, when the Onion polished off seven miles of County Road 603 on that October 18 morning and strode into tiny Pie Town, New Mexico, he felt pretty good. If he could average 30 miles per day–a tall request for just about anyone besides this freakish hiker–he might just catch Magoo.

But perhaps the most surprising thing about the Onion’s surge to the finish was that setting an obscure record–in a contest with no official scorekeeper or prize–had never been his main goal. He had hit the trail for the reasons many of us seek wilderness: to quiet his mind and spirit. He had recently left the Mormon Church and had taken leave from a PhD program; he was troubled by unresolved feelings about God and his future. Magoo, likewise, was motivated by a higher quest: He was a successful MBA who had chucked the corporate world for a dream of turning hiking and adventure into money. Was he insane to think that the dirt path could also be his career path?

Before carrying on, the Onion stopped at the Pie Town post office and picked up four resupply boxes. (Both he and Magoo would occasionally slip into civilization for provisions or to communicate with the outside world.) One box had 20 maps in it. The others mostly contained the jolt-inducing chocolate-chip cookies, chocolate-covered almonds, peppermint bark, and Oreo Cakesters that sustained him on the trail. There was also another reason for the Onion to feel revved. Mr. Magoo, he noticed, had signed the post office’s CDT trail register just six days earlier. The gap was closing. Hopeful to get in another 25 miles before calling it a day, the Onion promptly walked into the New Mexico sunshine.

Tattoo Joe. Trauma. One Gallon. Nimble Will.They’re all top ultra-distance backpackers, and nobody’s ever heard of them. Which is pretty much the way they want it. That’s because the ultra-distance community–a fraternity of maybe a dozen folks who think of an Appalachian Trail thru-hike as a warm-up–typically prefer to walk 200 days straight, and then reenter civilization only long enough to mastermind a plan to leave again.

“Money is just a means to get to do the next trip,” says 27-year-old Justin “Trauma” Lichter, who hiked 10,000 miles in 2006. “As for fame, why would I want that? It just complicates things.”

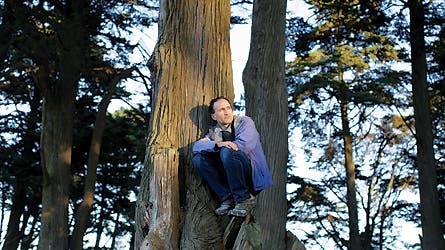

Francis Tapon, on the other hand, hungers for attention. The Bay Area-based Tapon sought to become the first person to yo-yo the Continental Divide Trail–that is, thru-hike it and then double back to the start–for the adventure, but also to raise his profile. Tapon is an entrepreneur who hopes to parlay his hiking and travel into a series of self-help books, equal parts life-coaching and travelogue, and become a successful author.

Tapon, who has engaging hazel eyes and a celebrity’s smile, released his first effort, Hike Your Own Hike, in 2006. It’s based on his thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail five years earlier. To this reviewer, the writing is uninspired and the advice often clichéd: The author doesn’t need to tell us that exercise is good or that smoking is bad, or that we should find a job we love because life is short. But Tapon likes to think of his messages as timeless reminders. To him, backpacking and life should both be distilled to their essences.

“Backpackers always say, ‘What do I really need?’ That’s how I systematically look at my existence,” Tapon told me in Berkeley, California, last fall. “I may not be as funny as Bill Bryson or as good as Stephen Covey. But I think my books can form a niche.” At press time, he’d sold 2,000 copies of the self-published Hike Your Own Hike, placing him somewhere around 427,000 on Amazon’s sales-rank charts. But the low figures don’t discourage Tapon. Few things do.

“He doesn’t realize limits like most people, whether they’re true limits or not,” says Lisa Garrett, who thru-hiked the AT with Tapon and remains a close friend. “Francis wants to do something that’s a little more courageous and pushes boundaries farther.”

Such courage enabled him to do something few people do: reject the American dream. The Harvard-educated Tapon got his MBA in 1997, launched a Silicon Valley startup, and promptly became a subject in a feature about next-gen entrepreneurs in The New York Times Magazine. He then worked at another technology firm, and by 2005 Tapon was pulling down $200,000 a year at Microsoft. But in one way, Tapon has always been like his minimalist-minded, ultra-distance hiking peers: He could never get excited about money and its trappings. His immigrant parents–a French father and Chilean mother–were self-made, and taught Tapon and his older brother not to place importance on material goods. Tapon claims he has never owned so much as a couch, and to this day he frugally counts his pennies and doesn’t have his own place. Between trips, he stays with old friends or his mom. So when he started camping in 1999, it’s not surprising that he was immediately drawn to its simplicity. Soon came the AT thru-hike, followed by a thru-hike of the PCT in 2006. “The AT transformed me. It helped me reprioritize my life,” says Tapon. “I wanted to have rich and fun experiences.”

The unprecedented CDT yo-yo, he expected, would provide a fat scrapbook’s worth of memories, and also gain him some celebrity as an ultra-distance backpacker. Before leaving, he lined up 13 companies to supply him with his every on-trail need. Before he finished, local REI stores would commit to several post-hike speaking engagements.

He started last year in Antelope Wells, New Mexico, on April 6, and cruised through the first month. In Colorado, where he endured 20 snowstorms in fewer than 30 days, he had plenty of unforgettable experiences. One day while in the skyscraping San Juans, Magoo bypassed a horribly long descent by pulling off an epic, seat-of-the-pants glissade in which he lost all his maps but came away unscathed. It was for moments like these that his friends once gave him the handle Mr. Magoo: Like the old cartoon character, Tapon seems to glide through life’s toughest moments.

At least for the most part. On another May afternoon, Magoo wasn’t so lucky. Trudging through the powder atop broad-shouldered, 13,300-foot James Peak, Magoo was persuaded by the partially blue skies to continue walking the ridge until nightfall. But as the sky darkened, he couldn’t find anywhere to camp. The light load he carried didn’t include a tent, and his paper-thin sleeping pad was complemented by an equally minimalist sleeping bag. Ultimately, he wedged himself between some rocks and shivered through two hours of sleep. It was an experience rough enough to make even the most determined backpacker nostalgic for cubicle life.

“It’s a lot of work and frustrating at times,” Tapon wrote in an early email to the Onion, admitting that he’d spent days in the desolate and snowy San Juans screaming at the top of his lungs. “But I have all these sponsors that I can’t disappoint. That’s been keeping me motivated.”

Ultra-distance backpacking surfaced in 2001, when “Flyin’ Brian” Robinson became the first hiker to conquer hiking’s Triple Crown in a calendar year. Flyin’ Brian had approached the feat–thru-hiking the Pacific Crest, Continental Divide, and Appalachian Trails–as if attempting a giant math problem. Prepare one’s body to endure thousands of trail miles? Run 50 miles per week before leaving. Lighten one’s load? Use your poncho as a makeshift tent. Give yourself enough time? Start on January 1. Ten months later, Robinson had done what many said was impossible.

Garret Christensen gets Robinson’s desire to hike for thousands of miles without a break. Unlike the rest of his life–his Mormon upbringing, as well as his graduate school classes in economics at the University of California at Berkeley–Christensen thinks that ultra-distance backpacking adds up. It makes sense.

“When I’m backpacking, I don’t have to worry about anything else,” Christensen told me on a hike in Tilden Park, outside of San Francisco, shortly after he came off the CDT. Sporting a Muir-worthy beard over his tanned face and dressed head to toe in lightweight nylon, he seemed to be in his element. “All I have to think about is tiny logistics, like getting food,” he continued. “Other than that it’s walking. It’s very simple.”

Christensen grew up in Reston, Virginia. His dad worked as a defense industry engineer, and his mom looked after Garret and three older siblings. They were devout members of the Mormon Church. Christensen’s parents’ only apparent failing seems to be that they didn’t watch young Garret’s diet too closely. He became a junk-food junkie.

His diet didn’t slow him down. Christensen became an Eagle Scout at 18 and thru-hiked the AT in 2002. He developed a sharp wit and a facility with numbers, graduating magna cum laude from Brigham Young University in 2004 and writing a 40-page thesis that linked economic theory with summiting Mt. Everest. That same summer, Christensen squeezed in a thru-hike of the PCT, discovering in the process that he could travel great distances without much rest. He walked end to end in a blazing 93 days. Then, after the hike, he jumped straight into Cal Berkeley’s rigorous PhD economics program. He says it was a logical step. “Mathematically, there was always a right answer in economics,” he says. “Plus, as an undergrad I was good at it.”

But Christensen’s drive and talent didn’t always work in his favor. In 1998, while serving a two-year mission in South Korea, Christensen followed Mormonism’s renowned work ethic so dogmatically–tirelessly trolling for converts on Seoul’s streets–that he became unpopular with his peers. He thought he was doing the right thing, and in turn poked at the other missionaries with his nasally voice and condescending attitude. They retaliated, nicknaming Christensen “The Emperor.” “Garret was born knowing that he was the smartest person in the world,” says his mother, Kathy Christensen. “He showed impatience for people who didn’t know as much as he did.”

Thus his arrival at Cal was a shock. The classes were hard. Other students were more motivated. Christensen was unexpectedly disoriented. “I hated school,” he says. “Why was I there?”

In the fall of 2006, Christensen took time away, helping to track an economics professor’s study in western Kenya. While in Africa, Christensen arrived at another disillusioning epiphany. The Mormon services there were held in English instead of Swahili. If God really existed, he wondered, wouldn’t he speak all languages?

In debating Mormonism with his fellow visitors, the religion felt increasingly inconsistent and ambiguous–as if it were a flawed set of statistics. “In Africa, some of my openly atheist roommates were happier than me,” he says. “For a while I was scared of the alternative–that if there is no God then humanity will end. Then I looked at them again and thought, ‘well, you might as well be happy.'” After considerable consternation, he left the Mormon Church. He now considers himself “an agnostic, leaning to atheism.”

His parents were profoundly disappointed.

“We still have hope,” says Kathy, his mom.

Christensen returned to the Bay Area in early 2007 and promptly took another semester off. Uncertain if he wanted to continue in school, unmoored from his religious upbringing, and feeling separation from his parents, Christensen decided to seek answers on the trail. He set his sights on the yo-yo of the rough and lonely CDT.

“I wanted to take a large amount of time off,” says Christensen, “and give society the finger.”

Nobody hikes the Continental Divide Trail in anticipation of finding a big party. The path bisects some of the country’s most rugged and least populated lands. Unlike the Pacific Crest Trail and particularly the Appalachian Trail, it isn’t punctuated by a lot of hiker-oriented shops, watering holes, and gathering spots. Trail experts estimate that only 50 hardy backpackers, or about 4 percent of what the AT attracts, annually attempt to thru-hike the CDT.

The Onion was in his element from the start. He began hiking almost a month after Mr. Magoo, due to school obligations, but he soon found solace breathing New Mexico’s clean air and staring into the broad Southwestern sky. “I’ve hiked 577 miles so far, and I’m having a really good time. If my sister ever expects to get a phone call from me, she should quit sending me job announcements,” he wrote from Ghost Ranch on his blog on May 22, sounding reassuringly Onion-esque.

The Onion sang made-up songs (like the one about hemorrhoids belted out to the tune of “America the Beautiful”), strummed air-guitar, and focused on blessedly un-heavy thoughts, like what he’d eat for dinner (frequently S’mores-flavored Pop-Tarts). Sure, sometimes he’d get wound up thinking about people who outwardly seemed completely rational–yet unquestionably accepted God. Take his devout dad, who was so logical that the Onion called him Mr. Spock. And like Mr. Magoo, the Onion struggled physically while traversing Colorado’s snowy San Juans. But his mind cleared as he got into the rhythm of his marathon-mileage days.

Both the Onion and Mr. Magoo moved like metronomes, hiking three miles per hour from sunrise to beyond sundown. They had no choice: Colorado’s wintry spring was behind them, yet they both had to anticipate the possibility of encountering an early Colorado winter on their southbound journeys. Mr. Magoo was so mindful of his need to make progress that he learned to keep moving–and avoid the spray–while peeing. He even brushed and flossed his teeth while walking. As for the Onion, he slotted four 15-minute breaks into his hiking schedule so that each day he had at least an hour of downtime. Neither of them even brought a stove (for the record, Magoo had the healthier diet, eating rehydrated couscous and textured vegetable protein from sponsor Bob’s Red Mill).

Many hikers might argue that covering so much ground, so fast, might diminish the wilderness experience. But it also afforded the opportunity to see a lot of wilderness, and enjoy moments that any backpacker would envy. Like one summer night in late July, after the Onion had beaten a path into northern Montana.

He was hiking at twilight, well after sunset, ascending an obscure gulch in Lewis and Clark National Forest, when he heard a disconcerting sound. Some sort of snort from an invisible source. “I pulled out my bear spray, and saw a shadow about 30 yards away,” he recalls.

The Onion walked a little farther through the woods, then heard what was actually a wolf, letting loose with a full-blown howl. “He was really close. Then another wolf howled east of me, then another. Pretty soon there were four wolves howling,” he later said.

At first, the Onion yelled back in defense. But he quickly surmised that the animals posed no threat, and that sharing the night with a pack of wolves was actually one of the most incredible experiences of his life. “Definitely not a moment when I thought about how I should be paying more attention to grad school,” he later quipped. “I stopped screaming and maybe hiked another 200 yards. That’s where I went to sleep under the stars. It was awesome.”

Likewise, Mr. Magoo had his share of goosebump moments. One early August day, a southbound Magoo ignored the “Closed” sign on the trail that led to Montana’s Chinese Wall–a thousand-foot high, 12-mile-long stretch of spectacular limestone cliffs that’s a justifiably popular attraction. At the moment, hikers had been prohibited from the vicinity: The surrounding Bob Marshall Wilderness was under siege from a devastating fire. Nevertheless, Magoo was intent on seeing the wall and kept on walking, even at the risk of incurring a $5,000 fine.

“Maybe it wasn’t the brightest thing to do,” Tapon later admitted, “but I was determined to see the wall.” He was so impressed with the rock formation that he decided to spend the night there (also against the rules). In turn, he was treated to an evening concert delivered by a nearby herd of elk, which alternately provided the percussion of their stampeding hooves and the sweet bleats of their young. Even a time-pressed ultra-distance hiker knows how to soak up a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Unlike the Onion, Magoo captured an extraordinary amount of his trip’s epic moments on camera. He carried a high-def movie camera that he frequently pulled out to ensure there would be plenty of footage for his website, book images, slide shows, and presentations. There’s Magoo atop Colorado’s Mt. Elbert in a blizzard. There he is at the Canadian border and in the New Mexico desert. Here’s a funny photo of cows humping.

The two hikers also differed in the way they occupied themselves on the trail. Where the Onion made up songs and listened to music on an MP3 player, Magoo’s MP3 device was loaded with books on tape (including inspiring biographies), motivating speeches (like those written by Thomas Paine), and even language lessons. Yes, you could’ve walked up to Magoo in the middle of forested Montana (although few did–he didn’t see a single backpacker for the first 2,000 miles of his journey) and caught him repeating the phrase “I am an American!” out loud in pidgin Mandarin. “There are one billion Mandarin speakers,” Tapon later explained. “Someday I’m going to Asia, and I’ll definitely make that trip into a book.”

If Mr. Magoo was going to lose this race, he wanted to lose it fair and square. Which is why, by mid-August, he was dumbfounded by the Onion’s route. As Magoo dutifully followed some of the CDT’s PUDs–”pointless ups and downs”–on the Idaho-Montana border, the Onion’s intentions gnawed at him.

Mid-journey, the Onion had sent an inquiry to a CDT electronic mailing list. The email sought advice on taking a substantial and seldom used shortcut. It began in Montana and bypassed the annoying PUDs, thus shortening his return trip by some five days, or about 150 miles.

“I’m sure it’s not close to the Divide or anything,” the Onion had written. “But if it saves that many miles and makes it easy to hike straight north-south through Yellowstone, I think it might be neat to do.”

Mr. Magoo’s hackles were uncharacteristically raised. He didn’t find the proposition “neat.” He’d been sincerely disappointed that he and the Onion hadn’t crossed paths near the Canadian border, where the fires had contributed to them taking different routes. But after reflecting on the email, Magoo no longer knew what to think of the Onion and his hike. Magoo had always stuck close to the CDT’s “official” trail, and the Onion had already bypassed some of its meandering sections.

The modifications had contributed to what by August had become Magoo’s noticeably eroding advantage. Throw in his day off here and there to update his trip on cdtyoyo.com (ever the entrepreneur, he had created the website to track his progress), or to download photo files, or just to catch his dang breath, and Magoo had lost so much ground that he was probably only two weeks ahead of the tireless Onion. Now add this bombshell of a route change, which might halve Magoo’s lead again, and, well, the frontrunner felt compelled to question the Onion’s motivation.

“It was such an unorthodox shortcut. I thought people would conclude that he was disqualifying himself from his attempted yo-yo,” Magoo later explained. “I thought he might be joking around.”

To which the Onion would respond: Huh? To him the shortcut was about doing something new, and avoiding those annoying PUDs. The abbreviated southbound journey would also help him more quickly reach the imposing San Juans, which he wanted to traverse before the snow started falling. Besides, didn’t Magoo literally write the book on hiking your own hike?

“I was still on an unbroken journey, on foot, from Mexico to Canada and back,” Christensen later said. “If I wasn’t yo-yoing the trail, then no one in history has even hiked the trail.”

And yet in the small but squabble-ridden world of thru-hiking, where those who stick religiously to a path are considered superior to those who take shortcuts, such a question had never been debated. No one had asked: What’s considered a legitimate yo-yo of the Continental Divide Trail?

The parameters are clear on the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails, which have well-established routes. But the CDT is different. The under-funded associations that care for the path haven’t secured all the necessary land easements or erected sufficient signage. To many, the CDT is more like a corridor. Conquering it is as much about improvisation as it is about enjoying majestic vistas.

“There is an official trail,” says Jim Wolf, director of the Continental Divide Trail Society and a person as qualified as any CDT nut to be judge and jury on the issue. “But the ethos among trail users is do whatever you damn please.” In late August, the Onion arrived in Yellowstone via the shortcut, and was soon marveling at Mammoth Hot Springs. He shared the trail with bison and cooled off in the crystal-clear Yellowstone River. He had no regrets. “To me, the fun was making up your own route,” he later said.

Just a bit farther south, Magoo also decided to abandon the CDT–albeit in search of something longer and harder. Wearing trail-running shoes, he did his best to stay atop the actual Continental Divide in Wyoming’s Wind River Range, which is a lonesome wilderness of jagged rock, glaciers, and crevasses. It’s not the best place to be without crampons, let alone an ice axe. But this hiker was the intrepid Mr. Magoo, who wanted, even needed, exciting experiences.

“The route through the Winds was going to make my trip more difficult, and that was going to be an interesting story to tell,” he later said. “I could use that material to inspire people.”

Entering the trip’s final stretch, Magoo felt he held an advantage over the Onion, and not just because he was still ahead. He’d done exceptional justice to the CDT by taking its longest and often most challenging routes, and he wouldn’t hesitate to convey those accomplishments to his readers and sponsors. Whether any of them would care about such nuances didn’t matter. In the end, the obsessive Magoo was pleasing one person: himself.

“I didn’t want to come back from this trip in some sort of gray area,” Tapon would later explain somewhat defensively. “I would hate to have an asterisk next to my name in the record books. I don’t want to be the Barry Bonds of hiking.”

The Onion made Mr. Magoo sweat New Mexico. Earlier in the trip, Magoo had envisioned his return visit to the state as a slowly hiked victory lap. But with less than a week’s lead, he scratched his leisurely itinerary and moved his finish date up. That meant going as hard as he’d ever gone, hustling through places like Ghost Town and El Malpais, and walking well into the pitch black as the autumn days turned shorter. “The Onion was on my back,” he later said. “I hiked into the night because I knew that’s what he’d be doing.”

At least Magoo didn’t do it all alone. Five thousand miles into his journey, he finally found a hiking partner who could keep up. Clint “Lint” Bunting, a 30-year-old roofer from Portland, Oregon, was a fit and good-humored southbound CDT thru-hiker. He cracked funny jokes and bantered with Magoo about women and the art of Dumpster diving. They walked together for five days. “We had a blast. He was super friendly,” Bunting later said. “Although Francis did try to tell me about the time wasted by stopping to pee. At one point he busted out some math formula.”

Magoo arrived at the border town of Columbus, New Mexico, on October 25, 201 days after he started. The Onion finished on October 28, 178 days after he began. The two of them never joined in a victorious, grimy handshake. Mr. Magoo preferred it that way.

“I thought that we did sufficiently different hikes that I didn’t want to be classified together. You know–pictures of the two of us,” Tapon said shortly after he finished, estimating that his route had been about 300 miles longer than the Onion’s. “There can only be one Neil Armstrong.”

“I’m still one of the first,” Christensen would later say. “And I’m the fastest.”

Awards night, so to speak, came a few months later at an REI in Berkeley. Tapon had created a highly inspirational, 90-minute multimedia presentation out of his CDT adventure that he would present at several of the co-op’s stores. The lights dimmed, and Tapon launched into his script.

“When I was in the corporate world, I would walk down these corridors and think, ‘Is this what life is about?'” he began. “Then I said, ‘You know what, I really don’t want this anymore.'”

The digital film rolled, and Tapon wowed the respectably sized crowd. There was beautiful footage from the trail and triumphant self-portraits, although at times the latter were overdone and resembled Viagra ads. Tapon also flashed his sponsors’ logos on the screen and warmly mentioned that his book was for sale.

Christensen was there, too. In the front row, holding his bicycle helmet, after having ridden from his low-rent home (he doesn’t own a car). Tapon, however, failed to introduce his CDT foil to the crowd.

It was awkward. Here were two men who had, for half a year, literally shared the same ups and downs, the same wonderful and miserable outdoor experiences. Yet as close as they got on the trail, it was now Tapon getting the attention. He closed with an update: He had recently been hired to help launch Booknolia, a Bay Area social-networking startup with a focus on books and authors. His next travel and self-help book, The Hidden Europe, will be out in 2009. Then there would be trips to Asia and Africa, and books following those adventures.

After the presentation, Christensen stood up and thoughtfully stroked his beard. Like most of the small number of ultra-distance backpackers–people like Tattoo Joe and Trauma–he was destined to remain anonymous. But Christensen didn’t seem to mind too much. In the wake of his 5,600-mile therapy session, he had changed specialties within his PhD program, and seemed mildly excited to have swapped “labor economics” for “law and economics.” Christensen was volunteer-tutoring school kids. And he was hanging out with Mormon pals without apparent conflict–happy hiking, he says, confirmed to him that his decision to leave the Church was the right one. His thinking had already drifted to his next adventure, a cross-country cycling trip planned for 2009.

The crowd at REI that night couldn’t possibly have known that there were two CDT record-setters in their midst. Nor that the pair had come within three days of finishing simultaneously. Only a few friends and thru-hiker obsessives even knew there had been a race, of sorts.

In the future, of course, who was first and who was fastest will matter hardly at all, as each hiker contends with his own measure of success. Will Mr. Magoo prosper? Will the Onion remain content? As with all of us, those questions can have no final answer. And that’s something to ponder on a good, long hike.

Andrew Tilin insists he has hiked more than 10 miles in a day. But only once.