The Long Way Home

(Photo: Holly Wilmeth)

In spring 2006, Karl Bushby crossed the Bering Strait from Alaska to Siberia, walking on shifting ice floes and swimming gaps of open water. It was an audacious endeavor, to say the least. Bushby and his partner, Dimitri Kieffer, towed 200-pound sleds through a rubble heap of fractured ice. They skittered up 30-foot-high pressure ridges, scrambled along thin shelves of ice, hoping they didn’t crack, and laboriously dog paddled through 32°F pools of salt water that were often clogged with frozen slush. At one point, Bushby and Kieffer got swept 52 miles north as they tried to push west, because the ice floes moved with the wind. They ended up traveling roughly 150 miles over 14 days to cross the 53-mile-wide strait. Near the end, the pair had to jettison every ounce of excess weight in order to complete the journey. “My expedition was on the line. So we threw the supplies overboard—the shotguns, the radio,” Bushby recalled later.

The BBC and other media covered the successful traverse with fanfare. And not only because the pair was following, almost literally, in the footsteps of prehistoric travelers who crossed a land bridge between Asia and North America. The feat also marked the most challenging stage of Bushby’s Goliath Expedition, the singular campaign that has consumed him since 1998. He aims to complete the world’s longest hike, becoming the first human ever to walk and ski an unbroken path around the globe or, more accurately, from the tip of South America back home to industrial Hull, England. Before setting off, he’d done nothing to suggest he was capable of such a trek. But when he reached Russia with the technical crux behind him, and some half the distance done, it appeared that the one-time British Army paratrooper might actually finish the 36,000-mile journey.

But what should have been the expedition’s high point quickly became the low. Russian authorities arrested Bushby and Kieffer for entering the country illegally and deported them back to the U.S. Kieffer, who had joined Bushby only for the Bering Strait crossing, didn’t plan a return to Russia. But Bushby’s efforts to resume his journey have been repeatedly hampered by visa and financial problems. Over the following six years, Bushby managed nothing but sporadic stints on the Siberian tundra, which is only passable on foot in subfreezing conditions. On his spring 2011 visit, he inadvertently strayed into one of the off-limits security zones Russia maintains near its borders. Authorities barred him from returning to Russia for five years. He enlisted a lawyer to lobby Moscow’s visa czars, but the Goliath Expedition appeared stalled, perhaps indefinitely.

Still, Bushby had accomplished much simply getting this far. Few would have called it a defeat if he abandoned the journey. Every hike has an end, right? But Bushby didn’t go home. Nor did he go forward. He simply disappeared from the adventure stage. Which is when Karl Bushby became captivating in a whole new way. Where had he gone? What happened to the record-setting hiker who couldn’t keep hiking?

“I’m 42 years old and I’m broke and I’m homeless,” Karl Bushby lamented as he trudged along through the coarse brown sand of a beach in Melaque, Mexico, where I caught up with him last year. “I’m a professional parasite. I’m a professional hobo. I’m sleeping on other people’s couches. I’m 42 years old, and I have to walk other people’s dogs, just so they’ll feed me. My job is picking up dog shit!”

Bushby paused now, and when I looked over at him he was faintly smirking, charmed by the dolefulness he exuded as we made our way through the twilight toward the tiny village on Mexico’s west coast. There was a sparkle in his blue eyes, but a fleeting one. Since late 2008, mostly living in Melaque (pronounced muh-lah-kay, population 8,000), Bushby had been undernourished, subsisting on less than 2,000 calories a day as he cadged lodgings from friends and did them occasional favors in return. His skin was pallid, as though he were back home in the north of England, where his mother still works in a confectionery factory, and his movements were restrained—sluggish, even. ‘I’ve shut down the extremities. These days I’m just preserving my core,” he said. His tone was at once morose and faux dramatic. “I’m at the mercy of other people’s kindness. I’m a nobody. But in a matter of months, of course, I could be conquering the world.”

Well, not exactly conquering the world, but slowly plying his way across it. From 1998 to 2006, Bushby averaged about 2,000 miles a year. Not noteworthy by thru-hiker standards, but no one will question the pace if he completes the journey. The unprecedented length, along with potentially deadly obstacles like the Bering Strait’s shifting ice, make it a hike no one will likely ever repeat.

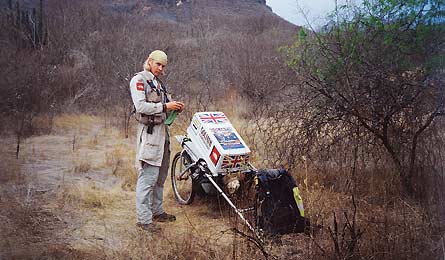

The expedition began, he said, as a bad bet. “I had something to prove to my paratrooper mates.” He also had something to run from in 1998, he was still embroiled in the aftermath of a nasty divorce. He flew to Punta Arenas, Chile, with $800 and a wheeled cart full of gear.

Strangers fed and sheltered him. He scored a few meager sponsorships, and he just kept plodding along. Bushby walked up South America’s Pacific coast, battling wind in Patagonia and long waterless stretches in Chile’s northern deserts. He crossed Central America’s Darien Gap, a guerilla-ridden jungle region where he backpacked into a no-man’s land against the advice of the Colombian military. He walked through sizzling heat in the Southwestern U.S. and numbing cold in Canada and Alaska. Then, famously, he crossed the ice to Russia in 2006. And then, not so famously, he retreated (by plane) to this beach town in Mexico, where he could look for sponsors—film producers were nibbling as he conserved funds. The unemployed Bushby had a grand total of $700 in his bank account when I visited him and he couldn’t even access that money, having lost his bankcard. The replacement was still en route. As we walked through the sand, Bushby cracked open his wallet to reveal a single 20 peso bill, worth about $1.70. “That’s it,” he said. “That’s all I have at the moment.”

His words sprouted a diagram in my mind: I envisioned life as a series of squiggly, branching lines. We make choices, and nearly all of us start out incubating some grand, youthful ambition. We want to write novels when we grow up, or scale unclimbed peaks. But then we do grow up, and we become practical. We choose lines that are easier, more conventional. We limit our adventures to what fits in the vacation schedule, and eventually, well, we do end up getting that minivan.

Karl Bushby refused to part with his grand plan, and the diagram of his life reflects that decision. He has experienced moments of triumph, to be sure, but he has also paid dearly for his stubbornness, as have others around him. When he set out on his hike almost 14 years ago, he left behind an eight-year-old son. Along the way, in Colombia, he met “the only woman who ever mattered to me.” They’re no longer together, though, and now Bushby passes the time in limbo here in Melaque. He is responsible to nothing but his dream. But does this make him the ultimate inspiration for adventure visionaries? Is Karl Bushby a latter-day Thoreau who dared to live deliberately? Or is he instead a sad case of arrested development: a freeloader who has failed to see that even the best hikes must end?

We kept walking. “Even the clouds here in the tropics are dynamic,” Bushby said now, looking up. “At a certain time of night, right at dusk, when the light is a certain way here, I feel like I’m in a dream state.”

Every long hike has its dream-like episodes—moments when the wilderness shines out and life seems exquisite in ways that it can’t amid the din of the civilized world. One winter night early in his journey, when Bushby was wending north through the Andes, he woke up in a tent covered with ice. Freezing rain dripped down on him from nearby trees. He broke camp and began climbing a mountain road, hauling his gear-laden cart. “The Beast,” he called it. “Up ahead of me,” he writes in his 2006 memoir, Giant Steps, “the clouds of fog meet the warmer air and explode into huge spirals, moving so quickly they look like giant flames, before they evaporate into nothing. On the hills to my left, huge dust devils are whipped into mini-tornadoes, sending columns of dust hundreds of meters into the sky.”

A headwind whipped up against Bushby. He kept climbing, his legs burning. When he reached the peak, finally, he was absolutely destroyed. Blowing sand stung his face. But he’d ascended more than 6,000 feet in three hours, and he was able to gaze out at the Atacama plateau and at the snow-capped peaks to the east.

And that night, as he sat outside his tent in the wind, eating pasta from a pan, he says he was awestruck by how clear and dark the starry sky was, looming above him, and also deeply content. “I was a very keen naturalist as a kid,” he explained to me in Melaque. “I used to bring wounded birds into the house and nurse them back to health. I gathered up dead animals and then glued their skeletons back together. But then when I went into the army I had to put all that aside. On this walk on days like that one in Chile I’ve been able to connect with nature again.”

Joining the military as an adolescent had changed the trajectory of Bushby’s life, and it seemed this walk was his attempt to reroute it. “I was a skinny, small lad,” he told me. “I was very immature, physically.” Still, his father, a star paratrooper in his day, convinced him to join the British Army’s paratrooper unit at age 16. “I was trying to enter a division of the army where 80 to 90 percent who try out don t make it,” Bushby recalled. He took the entrance test five times, and then, he said, “They cut me some slack. They let me in. It was the worst thing they could have done.”

As a paratrooper, Bushby was often required to parachute out of a plane and then run 10 miles in an hour and 45 minutes with 30 pounds on his back. “I had anxiety attacks,” he said. “I don’t know how many times I woke up in the medical center with IVs in my arms.”

Bushby stayed in the army for 12 years, but always, he said, “I was considered the weak link in our unit. I was an outsider. All the other guys had pictures of motorcycles and guns by their bunks. I had a poster of the solar system over mine.”

It’s unlikely Bushby ever imagined anything like Melaque when he lay in his bunk, gazing at the stars. The beachside town is a winter haven for Canadian snowbirds. In the summer, when I visited, it was steamy hot, and dead. Mangy dogs could lie on the pavement of side streets, unperturbed, for hours. At La Flora Café, a rail-thin American Buddhist, who revealed only his first name, Renee, sat alone every morning, sipping his coffee and staring contemplatively into the distance. When I asked him where he was from, he said, “Well, right now I’m living in this chair.”

In Melaque, Bushby was just another wandering soul, albeit more sociable than some. He was living here with just three t-shirts and two pairs of pants (his gear was stowed in Fairbanks) and mostly waiting for a call from Hollywood. A well-connected two-man production team was pitching TV networks a reality show starring Karl Bushby as a bumbling, endearing everyman explorer. “They’re very close to signing the contract,” he told me. “I should know by the end of the month.” (At press time, Bushby was still in the dark.)

While he waited, Bushby steadfastly eschewed anything resembling a job. “I’ve offered him work as a housecleaner,” said his friend Kyla Poirer, a Canadian who manages a swank Melaque hotel. “And other friends asked him to haul jet skis out of the water, but he always has an excuse. He says he’s got to be available to talk to the film producers.” Once, Bushby did a stint as a waiter at a fancy restaurant. “It was horrible,” he said. “After three shifts, I was done with the clients and all their snootiness with their sideways comments about how the tea wasn’t hot enough and their food wasn’t arranged on the plate the right way. If I did that for a living, I’d end up putting a plate over someone’s head.”

Most mornings, Bushby took his own table at La Flora. He enjoyed a bottomless cup of coffee, complements of La Flora’s owner, an admirer of his expedition, and he peered at his laptop, poaching a Wi-Fi signal from a nearby shop.

While Bushby is clearly consumed by his goal, he doesn’t glorify his achievements. At La Flora, we watched a BBC video about his 2006 Bering Strait crossing, and he never got boastful. “I’m an average guy, he said. I’m less than average. I’m an underachiever. All I’m doing is putting one foot in front of the other.”

On the laptop’s screen, the BBC’s narrator whipped himself into a lather over how cold the Bering Sea is, and Bushby rolled his eyes, then aped the man’s fretful upper crust British delivery. “One could perish in that water in a matter of seconds,” he crowed. “Seconds, I say! Mere seconds!”

The moment yielded more than a brief laugh. It also pointed toward the very quality that’s endeared him to strangers across two continents. He’s a world traveler, yes, and a record setter, but he remains a working class bloke from the north of England. Encountering him, you recognize at once that his quest is not Olympian, but human and plodding. You want to shelter and feed him. You want to buy him a cup of coffee.

With the Bering Strait behind him, Bushby will likely survive if he manages to continue his journey. Though what remains isn’t easy. Russia still presents formidable obstacles—skiing isn’t one of Bushby’s strengths, visa regulations are maddening, temperatures can reach -80°F, and chartered flights into Siberia can cost more than $12,000.

But once he clears those hurdles, it’s just a long hike home, through Asia and Europe. Bushby’s goal is to walk back into Britain via the emergency service corridor inside the Chunnel, the 31-mile train tube beneath the English Channel. Then he’ll continue on to the modest brick home in Hull, England, where his mum waved him good-bye so long ago. With the ongoing visa issues, Bushby can’t say with any certainty when he’ll complete the journey. But he knows this: He will not touch British soil unless he gets there on foot.

The don’t-go-home rule is, of course, completely arbitrary, since he’s allowed himself to fly to and from Alaska, Mexico, Colombia, and other locations. But he won’t allow himself even the briefest return to England. The self-imposed rule has defined Bushby’s life—he exiled himself from his son Adam’s growing-up. He missed birthday parties and much more. He said he’s certain that, if his parents die before he walks home, he’ll skip their funerals.

In Melaque, I pressed Bushby several times on the logic of the don’t-go-home rule and it was almost as though he couldn’t think outside of it. “I made a commitment,” he’d begin. I sensed a fear of failure that’s been decades in the making. In Giant Steps, Bushby describes reaching his late 20s and feeling frustrated and unfulfilled. And it wasn’t just his unhappy military career and ill-advised marriage. As a youth, he often felt weak and ineffectual. In primary school, he was made to stand on a chair in front of the class because he couldn’t spell (he was later diagnosed with dyslexia). His happiest childhood moments were spent outdoors, walking through the fields, exploring. So when he began contemplating a transformative experience for his post-military freedom, the answer came naturally. The world’s longest hike, the biggest test he could imagine, would be his chance to prove himself in a way no one could ignore.

But Bushby had a hard time transforming himself from army misfit to world explorer. Early in his trek, he sometimes ran out of food when the distance between towns was vast. He got so hungry, he says, that he hallucinated. Everything looked like food. “I’d see food in the bushes.” At times it was so windy in Patagonia that he had to walk tilting forward at a 45-degree angle, a posture that ravaged his ankles joints. In Alaska, he had to overcome snow and cold, the likes of which he’d never seen. During one three-day stretch, trudging along through soft powder in a -40°F wind chill near Dunbar, Alaska, he covered only a mile.

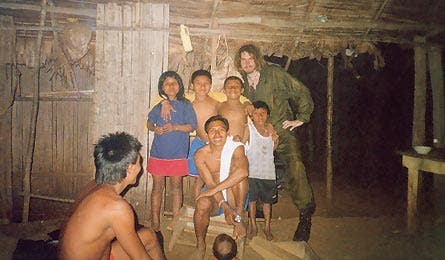

Despite these trials, Bushby led a charmed life during much of his travels, receiving aid from strangers along the way, and from his parents back in England, who managed grassroots fundraising efforts. In South America, especially, Bushby found a warm welcome everywhere he went. In tiny villages, he was greeted as a windswept blonde god.

“South America was like a boy’s adventure story,” Bushby said. “It was the happy experience I should have had in my teens—it was the best time of my life.”

Every morning I was in Melaque, Bushby checked his email, hopeful for a note from his producers. The correspondence was spare, though, for Jordan Tappis and Beau Willimon are busy fellows. Tappis produced the recent documentary, God Bless Ozzy Osbourne. Willimon is a playwright whose 2008 drama, Farragut North, was the basis of a recent film, The Ides of March, starring George Clooney.

Early in 2011, the pair laid out about $30,000 to send Bushby from Melaque to Chukotka, Russia, with a video camera, so he could shoot two months of lonely ice road travel. Now they were hopeful that the footage would sing to Hollywood titans. “Karl has a great story,” said Willimon when I called him. “He’s a down-to-earth guy, and he’s gone through everything in his travels. He’s been imprisoned, he’s fallen in love.”

The tragedy of this romance was a topic that Bushby kept returning to. Bushby met Catalina Estrada when he walked through Colombia, and he returned again and again to see her, even as he traveled north. With me, he spoke of walking the streets of Medellin with Estrada wrapped in his arms. Mostly, though, the love story is a tale about craving the impossible. For three years, Bushby tried in vain to get Estrada a visa, so she could visit him as he hiked. Finally in 2008, she wrote Bushby from Medellin: “Don’t come back here. We can’t do this any more.”

They have not seen one another since, but when I called Estrada in Madrid, where she currently lives, she spoke of Bushby with a sweet wistfulness. “When you see a person like Karl, you can think, ‘This guy is absolutely crazy’, or ‘It is incredible that a person could fight for his dreams.’ Karl makes me think that the human spirit is big. Karl is the big love of my life. When I was with Karl, I cried for seven years; I was so happy for seven years. It is very difficult to love a person who isn’t there.”

As we dined on the plaza in Melaque one night, Bushby acknowledged that he’s hurt people by refusing to live a settled life. “There are moral questions involved in what I’m doing,” he said, “and my son has paid the highest price. He grew up without a father at home. I don t know the guy. I don’t know my own son.”

Bushby is hardly the first explorer to prioritize his adventures over his parenting. Ernest Shackleton blithely left three young children behind when he sallied off on his last and fatal Antarctic expedition in 1921. Captain James Cook famously spent years at sea during his voyages. He had six children. Today’s adventure obituaries are filled with climbers and skiers who have left children fatherless. Still, Bushby felt guilty as he told me that, throughout his adolescence, Adam was depressed. “I bear a lot of responsibility for that,” he said. “And he’s still lost.”

Adam, now 22, works at a record store in Belfast. He has a tattoo of the grim reaper on his forearm, and he plays bass in a metal band. As his father sees it, Adam lives in a soul-sucking, culturally deprived environment. He doesn’t know what he wants in life.

Bushby believes that what Adam needs is precisely what he needed himself: a long hike. “Going to the Arctic would be a struggle for him,” he told me. “But it could change his life.”

In 2010, when the film producers flew Adam to Mexico, for his first paternal visit in six years, they asked him if he wanted to accompany his dad in the Arctic. With the cameras rolling, Adam Bushby entertained the idea. Later, I called Adam myself. He was genial discussing his dad, but also tentative and pained. “This long hike was something he wanted to do and I have nothing against it,” he said. “But it was kind of hard not having him there as I grew up. I did suffer in a way, I suppose.”

I asked Adam if he was ready for the Arctic. “Oh, the Russia thing,” he said. “We did talk about that, but I don’t know, that walking that’s my dad’s thing. I want to stay here in Belfast and get my own life sorted out.”

Of course, when Karl Bushby set out from England some 35 million footsteps ago, he too was bent on sorting out his life. Has he succeeded? If success means attaining stability and some measure of material comfort and a certainty about, say, where your next meal is coming from, well then no, he’s failed miserably. But if success means being at peace with the path you have chosen, Bushby appears triumphant. Even in Melaque, at an obvious low without money, without a certain timetable for returning to Russia Bushby exhibited only hints of sadness. “There have been times, walking,” he told me, “when I’m out in the pouring rain looking through someone’s window, into their warm living room. I’ve felt a tinge of jealousy.”

When I saw him at La Flora, just before heading to the airport, I was aware that I was leaving Bushby to fester in Spartan poverty. I just hoped that his bankcard arrived soon. It seemed as though his spirits were fraying.

But when my taxi pulled up, Bushby was smirking. “OK, then, mate,” he said. “It was a good time, wasn’t it?”

The cab rolled off. When I looked back, Bushby was already checking his email, and I knew that he was hunting for a message that would promise him a glorious future. For hope is always on his horizon. A couple of weeks later, as we talked over the phone, Bushby imagined emerging out of Russia, finally, and coming onto the homestretch of his epic hike. “Europe,” he said, “is going to be nothing but one big drunken party. I won’t even remember it. And I can’t wait to get there.”