The Long Trail to Jail

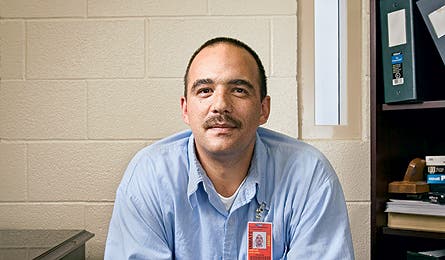

'David Lescoe in VA's Dillwyn Correctional Center (Michael Darter)'

David Lescoe in VA’s Dillwyn Correctional Center (Michael Darter)

Photos taken November 15, 2006 (Michael Darter)

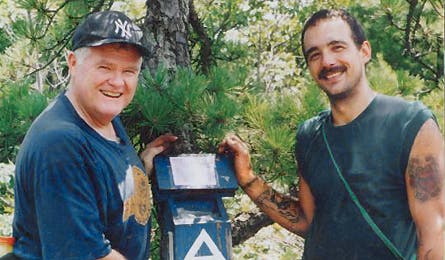

Dan Nicholls with Lescoe – July 29, 2004

Lescoe (left) with his mother and brother Andrew in 1975

Sandy Langalier was frightened when they came to arrest the friendly hiker, then annoyed, and then, like so many people whose lives were touched by the strange man, profoundly confused.

It was Friday, almost midnight, a chilly night in a drowsy Georgia town. Langalier was sleeping when she heard car doors slam, then loud, demanding voices. There was pounding on her door, lights flooding her house. She cowered under covers until she saw badges thrust up to her window.

By then, U.S. Marshals had arrested and handcuffed the nice young man who’d been staying in the trailer next door. His name was David Lescoe, and Langalier knew there must have been a mistake. Lescoe, 33, had been living in the trailer since he had wandered into Lizella just three months earlier, dirty, smelly, famished, telling tales of a miraculous conversion in the wilderness.

He was from up north–Pennsylvania–and he had laughed right along with the people in town who made fun of his Yankee accent. Later he would say that he had been seeking love and acceptance and that in Lizella, he had found it. The first building he’d entered was the Baptist church, and he returned there every Sunday morning.

In the days before he was taken away, he had been preparing a talk for the church youth group. It was a saga of salvation on the Appalachian Trail (AT), an epic account of suffering, and some sin, and the gentle light of forgiveness that was right there waiting if only a man was humble enough to walk toward it. It was a story as old as history, forever fresh. Once, in the woods of New Jersey, he had been lost. Now, in Lizella, he was saved.

Sandy Langalier told the men with badges as much. She told them they had the wrong guy. They told her to go back to sleep. That was two years ago. Since then, she has thought often of the man who so quickly insinuated himself into the life of her family, then just as abruptly left. She has wondered about the nature of good and evil, the promise of redemption, and the high cost of blind faith.

He is in prison now, serving a 10-year sentence for crimes to which he readily admits, while adamantly denying the accusation that drove him onto the trail in the first place.

Is Lescoe a good man who fell on bad times, or a bad man who preyed on the goodness of others? Was he drawn to the Lizella Baptist Church because he needed to confess his sins, or because he wanted to hide from those he had sinned against? Did the AT provide a weary and beleaguered man the bracing tonic of the wild, or a leafy hideout? For his entire life, Lescoe seems to have provoked troubling questions in the people who knew him. During the summer and fall of 2004, Lescoe provoked love, too. And burning anger. Men and women from New Jersey to Georgia sought his capture. Others prayed for his soul. Some did both.

He left Woonsocket, Rhode Island, on July 14, 2004, drove his Chevy Cavalier to a patch of dirt north of New York City, and started hiking. He says he was “possessed,” that he had been recently plagued by nightmares, “two actual demons coming through a mirror reaching out to grab me.”

He never knew his father, and never got along with his stepfather. His aunt and godmother, Shirley Sincavage, says Lescoe was molested when he was seven. He had his first beer at about 12, his first hit off a crack pipe a few years later, and at 32, when he first set foot on the AT, he had been in and out of three drug and alcohol rehabilitation centers, and jailed at least a few times–for offenses ranging from breaking and entering to failing to pay restitution to people whose property he had destroyed. Each time he left rehab, or jail, he vowed he was changing his ways. “David has said to us more than one time that he’s been saved,” Sincavage says. “He uses that God and Bible thing a little too much,” says his younger brother, Andrew.

They say that now, but back then, they believed him. His grandfather gave him the air-conditioning business he’d spent 30 years building. Lescoe’s mother cosigned for thousands of dollars’ worth of new equipment that he wanted to buy. She also cosigned on a home for her troubled son. Shortly thereafter, he left town, leaving her holding the debt on both.

He blames drinking and addiction to crack cocaine for many of his woes. He blames an ex-girlfriend who took out a Protection From Abuse order against him in his hometown of Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, forcing him to move away to Rhode Island, so, he says, she wouldn’t be able to falsely accuse him of violating the order. He blames his family for “abandoning” him. What he doesn’t mention is that the law was after him. Woonsocket investigators called Lescoe in the summer of 2004 and told him they wanted to interview him about a six-year-old girl’s statements that he had had sex with her. Lescoe said he was going to contact an attorney and would get back to them.

He says he is innocent, but “I was accused of things and I was scared.” So he fled. What better place than the trail? He had always loved the outdoors. By the time he was 16, he had completed all the requirements to become a Eagle Scout. He had spent much of his childhood in the woods near Nanticoke, spending so much time outdoors with his brother that dinner was usually cold when they finally came inside. “David could do anything,” says Sincavage. “He was handsome, he was a hard worker. He could charm anybody.” Says Andrew, “He was a normal kid until he got involved with the drugs and alcohol.”

After dinner, at night, he dreamt of a city. He wore a suit, carried a briefcase alongside other men with suits and briefcases, all advancing with purpose down the wide, glittering sidewalks of Manhattan. He had no idea where he was going, but he knew he was going somewhere. In the dream, he was happy. And now, monsters in mirrors. What could cause such a thing? Was it the drugs and alcohol? Having been molested? Was it that he met his father exactly one time, when he was six, and for the rest of his life had no idea whether the man was alive or not? To chart a bold line from a boy’s troubles to a man’s misdeeds is as satisfying as it is presumptuous. Men more ravaged than Lescoe have risen to lead nations. Other little boys, beloved, kill.

He left the Chevy toting a frayed and battered backpack, a jar of peanut butter, a box of crackers, and an 8-inch bowie knife with which he says he planned to cut his wrists. That he didn’t is just one of the questions, or inconsistencies, or mysteries, or murky instances of illogic, or flat-out lies that suffuses Lescoe’s narration of his wanderings on the AT. He also carried a notebook. One page was divided into two columns, labeled Things to Do and Things Not to Do. He wanted to convince other thru-hikers that he belonged. In the Things Not to Do column was “Be too eager to share shelter.”

He told people he met on trail that his name was Injun, a nod to his Sioux/Cree heritage. Nearly all long-distance AT hikers take on trail names. Not surprisingly, the men and women who go by Fang and Borealis and Slurps Like Ground Sloth as they trudge between Maine and Georgia are generally more attuned to the notion of getting away than to fitting in.

“There’ll always be people out there who are thinking things over,” says ranger Todd Remaley, the only full-time law enforcement officer now assigned to the AT. Remaley hiked the entire trail in 1990, when he was “at a crossroads. People use this as a place to change direction, to heal spiritually.”

What hiker would not want a trail name? The monikers strip away the trappings of civilization so many want to leave, if only for a little while. They also allow fugitives to wander with a little less anxiety.

Fourteen days after he began his journey, Injun came upon a sign atop a ridge near the New York/New Jersey border, not far from a town called Hewitt.

“I own a log cabin east of here, down the ridge,” the sign said. “You hikers are welcome to use an outdoor, rustic, but with privacy, hot/cold shower stall.”

The man who had posted the sign was 61-year-old Dan Nicholls. Nicholls, like Lescoe, was not a simple man. A born-again Christian, but divorced. A believer in law and order who corresponded regularly with and often visited David (Son of Sam) Berkowitz–one of this nation’s most notorious serial killers, born-again himself. Nicholls is a great samaritan who offers free showers and food to weary hikers–then tries to convert them.

Nicholls had been at the wake of a friend, and it was near dark when he arrived at the cabin. As he pulled up, he saw movement behind an oak tree in the yard and was alarmed, until he saw Lescoe’s pack. Then he relaxed; hikers had never bothered him. In fact, hungry, cold, and tired, many were excellent candidates for some old-fashioned religion.

Lescoe told Nicholls he was hungry, that he had recently killed and eaten a rattlesnake on the trail. He showed Nicholls the rattle to prove it. He said he was tired, depressed, spiritually adrift. He said that he had long wrestled with drug addiction and alcoholism, that his family had forsaken him. He said he was planning to kill himself. In a strange way, this cheered Nicholls. The hiker seemed ready to surrender his life to God.

Lescoe didn’t mention his time in jail or the molestation investigation. Nicholls offered him dinner, fed him two hamburgers and a cold Snapple. He let Lescoe do a load of laundry. He asked if Lescoe would like to sleep inside, in a spare bed. He showed him a videotape entitled “Hell’s Best Kept Secret.”

“I shared the Gospel,” Nicholls says. “The plan of salvation, that we’re all sinners, that we’ve all broken God’s laws, that we all need to come to Christ. I shared the simple plan of salvation. I was tempted to ask if he’d pray together. But I didn’t. I said, ‘Here’s what I’d do: I’d confess my sins before God.'”

That’s what Lescoe says he did–he confessed. He says he asked for divine guidance, turned his life over to Jesus. He says he felt an immense peace, a surge of joy he had never imagined. Later, after he was caught, after his numerous offenses against others, many would ask how he had managed to lie so convincingly about that night. But those people don’t understand Lescoe–and don’t comprehend the disconnect between belief and action that seems to animate his life.

The next morning, Nicholls remembers, Lescoe was smiling so much he said his mouth hurt. He confessed that the night before, before Nicholls had arrived home, he had stolen two tomatoes from a patch in the yard and eaten them “whole, just like apples.” The two men laughed at that. Nicholls was so moved by Lescoe’s apparent transformation that he invited his neighbors, a couple named Norma and Karl Stehle, over to witness the miracle. As Lescoe talked, all four wept.

Nicholls offered to drive Lescoe back home to reunite with his family. “What an answer he gave,” Nicholls wrote in an email that he sent to friends, “Without hesitation, Dave said he appreciated my offer…but right now the most important thing for him to do is to be alone with God, communing with Him and reading the Word as he continued on the trail…It would take about 2-3 weeks to get home, but that could be quality time in which he wanted to grow spiritually.”

It would be easy to dismiss Nicholls as a scripture-quoting sucker, so caught up in religious fervor that he couldn’t spot a con man scrounging in his tomato patch. But Lescoe possesses a talent for instilling belief. Once, he broke into a rural store in Tennessee and was rummaging around when the owner happened to enter through the front door. Lescoe convinced him that he had accidentally wandered in, and was just waiting for the owner to greet him.

The deepest mystery is not how Lescoe fooled so many people–he’s funny and self-effacing and has a gift for telling them what they want to hear–but why so many who were fooled still believe in him.

“I told Dave I would like to walk with him up to the top of the ridge and say goodbye there,” Nicholls wrote. “As he was packing, stocking up on food and tracts, he said again that this is absolutely the most beautiful day of his whole entire life. He couldn’t stop crying and laughing…What a difference true salvation makes! What Satan had meant for evil, God turned around for good! TAKE THAT, SATAN, YOU LOSER!”

Before Lescoe headed south, Nicholls loaded him up with gifts. A bag of trail snacks and a stack of religious tracts. Fifty dollars (the Stehles kicked in $20). A Bible. And finally, a walking stick made from an oak sapling, into which Nicholls had used a magnifying glass to burn Lescoe’s new trail name. Injun had shambled down the trail to Nicholls’s home. Striding away was a man who called himself Saved.

Back on the AT, Lescoe prayed. He prayed about one sin in particular–how at a shelter near Bear Mountain in New York, just a few days earlier, he had stolen a camper’s gear bag.

Her name was Sarah Holt, and she’d been heading north with four other thru-hikers when they came upon Lescoe. He invited them to share the shelter with him. When they declined, saying they wanted to sleep under the stars, he insisted, and they noticed. (He’d apparently not mastered his To Do and Not to Do lists.) Before they slept out, though, they hung their food bags in the shelter, away from rodents.

The next morning, Holt’s bag was gone. It had contained some chunks of pita bread and cheese, a cookpot, camping stove, titanium spork, toothbrush, toothpaste, vitamins a Leatherman knife, and insect repellent. The overly friendly hiker from the shelter was gone, too.

“At first I was confused,” Holt wrote in the Brunswick, Maine Times Record. “Hikers can almost always trust other hikers. You’re sharing an adventure and commiserating together. No distance hiker steals another’s gear.”

Lescoe prayed often on the trail. He told other hikers how much he prayed. He told them about his near-suicide, the miraculous experience of salvation. He didn’t ask for food, but many hikers heard the story and shared their food with him.

Lescoe has a dazzling smile and a friendly manner, all on display during some of the most perilous times of his life. Nicholls snapped a photo of Lescoe, and in it he has a mustache, the beginnings of a beard. He is six feet one, and in the picture, rangy. He has dark eyes, heavy eyebrows, dark skin, and arms covered with tattoos. Another man with those physical characteristics might evoke in strangers mild fear. Lescoe seemed to inspire compassion.

“That’s a gift from the Lord,” he says, “and I’ve been blessed with it.”

Just days after leaving Nicholls, Lescoe met a hiker named Brian Matthews, who called himself Dances with Moose. Saved told Dances with Moose the suicide/shower/coming to Jesus story. He told him about the stolen gear bag, and the guilt he carried. Dances with Moose offered to buy Saved a hamburger at a bar in Unionville, New York.

The hikers had a couple beers at the bar, too. “And that,” says Lescoe, “was where my first compromising began.”

As most people who have spent even a little time with Lescoe will attest to, it is not an easy matter to sort out the beginnings and endings of his compromising.

On the trail, Saved preached the Gospel to Dances with Moose, who wasn’t a believer. They debated spiritual matters, hiked together, camped together. But on the AT, paces differ, and “together” is a liquid concept. Lescoe slowed down. Matthews sped up. On August 13, Matthews arrived in Duncannon, Pennsylvania, hard on the Susquehanna River.

Matthews entered the town limping, and lucky for him, one of the first people he encountered was a 56-year-old bartender and cook named Mary Parry, better known to hikers and Duncannonians as Trail Angel Mary.

A trail angel, in the misty and ripe oral tradition of the Appalachian Trail, is a person who bestows acts of kindness upon tired and bedraggled hikers. If you have emerged from the woods onto a lonely rural slab of highway, thirsty and tired, and a car has appeared from nowhere, and the driver stops and offers you a can of soda, then you have encountered a trail angel. The legendary trail angels are those men and women who seem to fashion careers out of helping others. Dan Nicholls, with his offers of free showers and grilled hamburgers, certainly qualifies as an angel, though attaching prayer and salvation to hot water and grilled burgers might strike some as, while technically angelic, perhaps not as blessed as the same acts of kindness delivered with no strings attached. Which explains why Nicholls isn’t known as Trail Angel Dan.

Trail Angel Mary is revered among AT thru-hikers. That’s because of the Sunday night “feeds” she prepares, the three coolers she stocks with juice, water, and snacks and leaves on the trail near town, the way she lets hikers stay at her place, and her offers to help with broken gear and medical emergencies.

Parry drove Matthews to a local hospital to have his foot looked at, and afterward, she sensed that something more serious than a bum foot was wrong. “He was hem-hawing around on the way back,” Parry says. “Like he wanted to tell me something, but he couldn’t. I said, ‘Just spit it out.'”

Matthews told Parry about Lescoe. Matthews worried that the theft at Bear Mountain was gnawing at the man called Saved. He also worried about the woman who’d lost her gear bag.

When Lescoe came into town on the 15th, Trail Angel Mary confronted him. Stealing had always come easily to Lescoe. But so had apologizing. Especially when he was caught.

Wasn’t he the guy, she wanted to know, who had been confessing his sins of thievery to other hikers? He was.

And hadn’t he been saved, and seen the light? He had. Didn’t he want to set things right? He did. Well, what did he think would be the right thing to do?

Now that was a tough question.

Luckily, this angel also possessed a keenly refined sense of karmic payback, which she and others in the AT community refer to as trail justice. She said she would take the bag, with its stove and titanium spork, and she would add a box of food, and she would mail it to its rightful owner. Parry knew Sarah Holt’s name because the 27-year-old had been through Duncannon. Trail Angel Mary was a sympathetic listener. And she was kind. She’s called Trail Angel Mary, after all. But just like the samaritan with the prayer pamphlets in New Jersey and the confessing thief in front of her, she was also human. She would take care of setting things right with Holt. But she had another idea, too.

“I cleaned her bathroom,” Lescoe says. “I scrubbed it. You wouldn’t believe the mess that was, but in order to help pay for the postage and the whatever else, I done chores for Mary.”

In the simple calculus that defines trail justice, the world was set right. One man, repentant. One woman, about to be reunited with her trail bag, along with some extra chow for her troubles. One trail angel, with a sparkling bathroom. There was no need to involve the law, so no one did. People don’t strap on packs and enter a world of grubby goodness because they want more rules and regulations. The AT community would handle its own troubles.

“He should have been on my radar sooner,” Ranger Remaley says. “When the food bag was taken, the northbound hikers suspected who took it. But it took several hundred miles, when he was in central Pennsylvania, before someone confronted him. And nobody passed the information along to me, or to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. It would have been nice if we had heard about this. It didn’t surprise me, but it did disappoint me.”

Six days after Lescoe met Parry in Duncannon, Sarah Holt, still on her northbound trek, checked her mail in Hanover, New Hampshire. Awaiting her was a box filled with Pop-Tarts, fruit roll-ups, mac-and-cheese dinners, instant coffee, cocoa, and ramen noodles. There was also the cookpot, the stove, and the spork. And a letter.

“I won’t try to justify, explain, or rationalize what I did,” Lescoe wrote. “I just want to apologize to you for what I now know was wrong of me.”

Holt, like many hikers, knew about the mysterious instances of serendipity called trail magic. A bottle of water left at a campsite, stumbled upon by a parched traveler; a can of beans cached, then discovered by someone with a growling stomach. And now this.

“Somewhere along the line,” Holt wrote, “he did a spiritual 180.”

It would be a good story anywhere, but on the AT, where enlightenment and spiritual transformation inform the fantasy of long-distance hiking as much as crackling fires and twittering birds, it was a great story. At least it would have been, were it true. But once compromising begins, it’s difficult to pinpoint where it ends. Lescoe left Duncannon, and his trail angel/taskmaster, with a lighter heart and a lighter backpack. Compromised, but confessing. A sinner, but saved. An alcoholic who had recently knocked back a few beers. Cheerful, but broke. He called Nicholls, asking for more money, some socks. He called three times, but Nicholls wasn’t home for any of the calls.

Lescoe had let Jesus into his heart. He had not only confessed, he had made amends. He had even performed some undeniably humbling labor. But even a saint’s gotta eat.

He continued to separate hikers from their food. He would tell his story of loss and redemption, and bags would open, granola bars would appear. He poked into caches of food hidden along the trail. He caught perch and largemouth bass, grabbed the occasional ear of corn from a field. Once he chased a baby turkey, but it was too fast.

By late August, as Sarah Holt was celebrating the healing power of the AT, its newest reclamation project was about to do some serious compromising.

“When I had money and food,” Lescoe says, “I kept my eyes on the Lord and I was reading my Bible, hiking every day. Then I started running out of food, took my eyes off the Lord, and started worrying about my earthly needs. Took control from the Lord and put it back into my own hands. Trusted in my own resources, trusted in my old nature instead of trusting in the Lord.”

Translation: Saved started stealing. His trust in the Lord seems to have wavered most fiercely in Wintergreen, Virginia, a ski resort town filled with second homes. At one, he shattered sliding-glass doors with a rock to get in. At another, he clambered into a crawl space, then kicked through drywall until he broke through to a closet. By the time Lescoe left town, he had broken into four homes. At each, he drank liquor, gobbled food, grabbed clothes and camping equipment.

“I said to him,” says Wintergreen police investigator Steve Southworth, “‘You were only there for a few days, it looks like a small army was here.’ He said he was starving.”

On September 10, his last day in the town, Lescoe came upon a house with a green 1968 VW Beetle parked in front. “The whole time I was walking to the house,” Lescoe says, “I was telling myself I wasn’t gonna do it. I can’t do it. But after so many miles, what else you gonna do? You can’t live on tree bark.” He left with a North Face tent, trekking poles, a backpack, eight pounds of crabmeat, and a set of car keys.

Later, when he was imprisoned, and insisting that this time, locked up, he was really saved, I asked him why anyone would believe him after what happened in Wintergreen. He told me I had him all wrong. He had been saved in Wintergreen. He had been following God. But he’d been hungry. That’s when I started to understand the many people who had been so enraged and frightened and confused by Lescoe. I believed him.

Lescoe drove the Beetle 50 miles to an AT trailhead at the James River Foot Bridge, just north of Lynchburg.

Southworth suspected the thief had come from the AT, because of the stolen camping gear and the missing car. And he had a grainy security picture from Wintergreen’s Nature Center, one of the places Lescoe had asked directions. It showed a white man with dark hair and a light beard.

Southworth called the National Park Service, and ended up talking to Todd Remaley. By late September, based on Southworth’s leads, Remaley surmised that the hiker was on Forest Service land. So he called USFS officer Teddy Mullins. They calculated the hiker was walking 8 to 10 miles a day. That meant he’d be just south of Pearisburg, Virginia. That’s where Mullins found him, on the trail, on October 2.

Mullins carried a .40 caliber Glock, but he knew that Lescoe had a knife and might be suicidal, and he was under orders not to attempt an arrest by himself. So he made small talk. The hiker said his name was Saved, and when pressed, offered his real name. They talked about the storm that had just swept the area. Mullins said he was investigating damage on the trail. Then Mullins wished him well, hiked up to a mountaintop, called for backup from his cell phone, went back to his car, and drove eight miles down the trail. He waited four and a half hours.

Lescoe had seen the Glock, and later told Southworth that no officer investigating storm damage would be carrying a weapon like that. He continued hiking, but when he heard people talking ahead, he scrambled off-trail and hid in bushes until he was sure they had left.

A short time later, he came upon a hunting cabin. He broke in, grabbed some food and clothes, and fled. He would break into three more cabins and steal two more cars (including one in Tennessee), which he would use to drive farther south along the AT.

Remaley knows that thru-hikers are not the kind to get into others’ business. He also knows that the trail often beckons powerfully to people who aren’t exactly model citizens. But by mid-October, even among the drifters and the live-and-let-livers of the AT, Lescoe was getting to be a nuisance.

A lot of people in the AT community knew then that a southbound-hiking thief was in their midst. Not only that, but the reprobate had been peddling a story of salvation. And not only that, but many in the community had known enough to do something, but hadn’t. That bothered Janet Hensley, owner of a trailside hostel in Erwin, Tennessee, near the site of his last car theft.

“The news headlines said, ‘Appalachian Trail hiker steals car, evades police,”’ Hensley says. “In one episode, he managed to damage everything we had worked on for years. Some of the older people [near Erwin] automatically believe that everyone is capable of this, and now they have reason to be afraid of the hikers.”

Hensley was upset, so she posted a message on the hiker bulletin board whiteblaze.net. Its heading was one word: “Thief!”

“It is with a certain amount of anger and sadness that I feel that I have to start letting the AT community know about a situation,” she wrote. She included Lescoe’s description and trail name.

An outdoorsman who knew Dan Nicholls saw the posting and contacted the man who had helped save Saved. “And I put two and two together,” Nicholls says. He sent a photo to Hensley, who passed it on to others.

“The clubs were key in helping track David down,” Remaley says. “The ATC, the trail angels, the friends of the trail, the trail neighbors, the businesses along the trail all came together to catch a pretty wily, pretty seasoned criminal.”

Eventually, the photo ended up on Southworth’s computer. Southworth showed the photo to Mullins.

“That’s the guy,” Mullins said.

Southworth called Pennsylvania cops, who had Lescoe’s prints on file from his troubles there. When the prints arrived in Wintergreen, Southworth compared them to prints lifted from the break-ins. On November 10, 2004, police issued a warrant for Lescoe’s arrest.

By then, Lescoe was in Georgia (he had hopped a freight train near the Tennessee border). On Sunday, October 24, just 17 days before the warrant was issued, Lescoe had shown up at Lizella’s Baptist church. He was tired and dirty and hungry. He told parishioners about his hike. He told them about his salvation. He told them he yearned to walk with the Lord. He didn’t mention the child-molestation investigation in Rhode Island, or the meeting with Teddy Mullins in Virginia, or the stolen crabmeat and VW Beetle.

The pastor, Doug Davis, introduced the hiker to two congregants, Sandy and David Langalier. They invited him to Sandy’s mother’s place for lunch.

When they showed up at the home of Wanda and John Henry Clance, Wanda looked Lescoe over. “I said, ‘Son, you can eat at my home any time, but you have to wash up. You’re nasty.'” Lescoe went inside to clean up, and he came back outside to behold what surely must have seemed like a vision of heaven on earth.

Lescoe had arrived at the Clance house on the day of their annual barbecue. Everything was made from scratch. Wanda and her husband had butchered the hog themselves, as four generations of Clances before had been butchering hogs. “That boy ate and ate and ate,” Wanda Clance says. “I know he ate five barbecue sandwiches with homemade red sauce. Cole slaw and potato salad, too. He just ate.”

And thus began the happiest and most peaceful time in Lescoe’s recent life. The Langaliers helped him find a job at Carter’s Woodworking, and, after he complained that he wasn’t being paid enough, at Rogers Gutters & Windows. The Clances rented him a trailer next to the Langalier house. Lescoe spent many afternoons in the woods with David, 35, looking for deer to shoot, blazing new paths to hunting blinds, talking about everything and nothing. He played in the yard with the Langalier children, Stacy, 5, and Joshua, 1. He cooked and cleaned for Wanda, who was recovering from bypass surgery. “Well, of course I did,” he says. “She wasn’t up to it. She had just had a heart attack.”

Many mornings, before work and on weekends, he would show up at the Clance back door. “Hey, Mamma,” he would yell after knocking, and when Wanda yelled back, he’d walk inside. There, the 55-year-old grandmother of 19 and the 33-year-old hiker/criminal/lost soul would talk. He made Clance a shadowbox, which still hangs on her kitchen wall, and a serving tray.

“I was trying to start over,” he says. “I was trying to do the right thing.”

Lescoe now says he didn’t realize he was wanted by the law. Even from as consummate a storyteller as Lescoe, that seems hard to believe. On the other hand, Lescoe isn’t an unintelligent man, and if he did suspect authorities were searching for him, would he have been so stupid as to do what he did next?

He had promised Pastor Davis that he would share his miraculous tale of salvation with the church’s youth group on an upcoming ski trip. To get the most vivid details of his conversion story right–he knew how detail could juice a tale–he emailed Dan Nicholls, asking him if he would mind sending some of the journal entries and messages that Lescoe had mailed from the trail. To send the email, Lescoe used Sandy Langalier’s computer and email account. Langalier worked at the Crawford County courthouse as a deputy clerk, and the next day, she opened her email and saw a message from Dan Nicholls.

Nicholls had been in contact with Southworth for months. He had offered to have his phone tapped, if that would help catch Lescoe. “We were really skeptical of Dan Nicholls at first,” Southworth says. The cop knew Nicholls’s connection with Lescoe, about his deep belief in salvation, about his relationship with David Berkowitz.

Southworth’s skepticism was, as he admits today, wrongly placed. Because Nicholls, in addition to believing in a higher power, has strong opinions about the laws of man. “I was upset,” Nicholls says. “I just felt he had a Christian testimony to uphold and he failed in that area. What he did was basically spitting in the face of his Savior.”

So, after consulting with Southworth, Nicholls emailed back and asked for an address, which Sandy Langalier provided. The same day, she told Lescoe about the peculiar exchange she had just had with the man from New Jersey. It had been almost three months since Lescoe had wandered into Lizella. He had found a measure of peace. And now, it was about to be taken away.

Wanda Clance says she caught a glimpse of Lescoe that third week in January that she had never imagined.

“One morning before he was caught,” she says, “he had come over. But I think for some reason he wasn’t expecting me to be there. He didn’t knock. He didn’t call out my name. He just walked into the house, very quietly. And I think he was surprised to see me. He started explaining very fast why he was there, almost like he was covering up something, or planning something.

“He was a completely different person. He was very quiet. He was almost scary that morning, as if something was fixing to happen. He kept warning me about being careful about letting people into my home.”

Sandy sent the email on January 18, 2005. The U.S. Marshals pulled into the Langalier’s yard three days later.

“I woke up, and I didn’t know why,” Lescoe says. “I got up, turned the TV on, and then all of a sudden a vehicle pulled into the driveway, and they parked. And I got up off the couch and I walked to the door, and they asked if I was David Lescoe and I said yeah.”

He spent two weeks in the Bibb County jail before Southworth and Remaley showed up in Lizella. Remaley drove from Pennsylvania to Virginia, and the two men rode together to Georgia.

“The Langaliers were shocked,” Southworth says. “Mr. Langalier said he wouldn’t believe it until he had a chance to go to jail and talk to Lescoe. Which he did and then he came back and said, ‘How can I help you?'”

Before transporting their prisoner to Virginia, the cop and the AT ranger stopped at Circuit City and bought a digital recorder. The drive from Lizella to Wintergreen took seven hours, just Southworth and Remaley and a man called Saved. Lescoe confessed the whole way.

He was eventually convicted of 16 felonies in Virginia: eight burglaries, three counts of destruction of property, three grand larcenies, and two car thefts.

On a raw, windy November afternoon last year, Lescoe sat in the assistant warden’s office at Dillwyn Correctional Center, in the rolling hills of Virginia, 40 minutes south of Charlottesville. (Prison authorities won’t allow reporters into the dormitory where he lives.) Dillwyn is a medium-security prison, a collection of concrete buildings housing slightly more than 1,000 inmates, many of them parole violators. A cabinet in the office contains videocassettes labeled “Chow movement” and five years’ worth of “Serious Incident Reports.”

Lescoe walks a few miles on the track every couple of days, but is still 55 pounds heavier than when he was on the AT. The prison has weights, but he doesn’t use them. “I used to. I don’t need to be any stronger. The Bible says, ‘For bodily exercise profiteth little.'” Later, he says that “I might do a little strength training at the end of my time.”

He says he is sorry for the crimes he committed. He says he never molested anyone. He says he has mixed feelings about fleeing the Rhode Island investigators. Does he wish he would have stayed and cooperated, rather than walking onto the AT and into all sorts of trouble? “Kinda yeah and kinda no.” On that November afternoon, he quoted Scripture, talked about his troubled past, his uncertain future. He says he’s turned his life over to God, this time for good. He says people should believe him, because it’s the truth. He says it was the truth in New Jersey, too, next to the tomato patch.

“I was saved from that night on, but…I was still fleshly minded,” he says. “I didn’t totally know what it meant to be spiritual. And not carnal. My knowledge has grown immensely, especially being here. I mean, I can’t complain. I can’t say ‘God, why did you do this to me?’ I did it to myself. But He made it to His benefit. Definitely. Me being here has benefited the Lord. In my life. My understanding.”

“I was sincere then,” he says. “But I took my eyes off the Lord. I learned never to take my eyes off the Lord again. ‘Trust in the Lord in all thy ways.’ You know, ‘trust in the Lord in all thy ways and lean not to thine own understanding and then in thy ways He will direct thine path…'”

He won’t be eligible for release until 2013. Depending on whom you ask, and how well that person knows Lescoe, that day will be cause for rejoicing, or deep unease.

“Write that his family does love him and he knows he’s always been loved,” says his brother Andrew. “We’ve given him multiple chances. We got him out of jail; we were at his courts all the time. We did everything possible to help him straighten himself up. He could have made something of himself. But now? He’s an asshole. Plain and simple. I don’t want anything to do with him.”

“He’s got a wonderful personality,” says his mother. “He can win anyone over. My fondest memory? I don’t know. I try not to think of him.”

“I was the biggest advocate for David,” says his aunt Shirley Sincavage. “I don’t know whether I trust him or not myself. I don’t know. I’ve heard it too many times. I don’t know.”

It was so easy for Lescoe’s family to believe the young man with the open face, and the ready smile, and the confessions, and the many proclamations of conversion and promises to be good, if only he could have one more chance. And then he used up all his chances andfound another family, and even more chances. There, on that sinuous 2,175-mile ribbon of dirt, where the past is no more than a collection of fables, and the future doesn’t extend much beyond the next bend, or stream, a man isn’t judged by what he was, or might be, but by what he is. And Lescoe seemed to be just like a lot of other hikers–a little lost, a little unbalanced, but harmless. Until he wasn’t.

“I’m reluctant to believe anything he says now,” says Mary Parry, the trail angel whose bathroom Lescoe scrubbed. “He’s a smooth talker, and a smooth talker like that you can’t trust.”

“He says he took his eyes off the Lord?” says Janet Hensley, with a bitter laugh. “I’m not a religious person, but the best sociopath is the most likable, charming person in the world. They’re survivalists. They’ll do whatever it takes to get what they need. He found a group of people, some of the best, most trusting family in the world. And he was surviving. For him, that meant preying on people.”

“Very charming and a likable guy,” Steve Southworth says. “But I would consider people like that, of the criminal element, to be manipulators. We all hit mountains and valleys, and when he hits a valley, will he turn to the right people and make the right choices, or will he go back to where he was?”

Before I visited Lescoe in prison, I had been corresponding with him for almost a year, retracing his long, strange southbound trip, talking to those he robbed and others who trusted him, coming upon one shiny lie here, another murky truth there. Puzzling out what had really happened was exasperating at times, especially considering the dependably unreliable narrator at the center of the tale. Maybe that’s why I found such mean catharsis and petty joy in telling those he had “confessed” to on the trail about some little details he had left out, about the way he excused his post-salvation misdeeds.

“He says he took his eyes off the Lord,” I would say, and chuckle. Or snicker.

Many would chuckle along with me.

“He says he’s really saved?” asks Bob Gray, for 20 years the chief park ranger for the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, until his retirement in January 2007. Gray laughs, long and low. “Yeah, they usually are.”

“He’s the ultimate con artist,” says Mike Pierson, whose VW Beetle Lescoe stole, whose house he robbed. “He used Christianity as a cover, as an excuse, as a way around things. I think it makes a real mockery of people who are great Christians.”

“The allegations are molesting a six-year-old,” says Lieutenant Detective Timothy Paul, the public information officer for the Woonsocket, Rhode Island police department. (The investigation is ongoing, and authorities plan to interview Lescoe.) “I can see why he’d want to go find God or kill himself or something.”

I tell Lescoe’s story to a friend in late January. I have it down to two sentences and a punch line. “So this guy conned and robbed people on the Appalachian Trail, then he met a guy who fed him and let him clean up and they read the Bible together and he was saved. And then he conned and robbed a bunch of more people on the trail, until he got caught and thrown in prison. And now he says he’s really saved.”

The punch line usually gets a laugh, or some bitter wisdom about criminals and crocodile tears. This time, there’s silence.

“Hello?”

“Maybe he is saved,” my friend says.

“Yeah, right,” I say. More silence, and then I almost smack my forehead. Lescoe isn’t the only one with a sad story. In her 20s and early 30s, my friend had lost friends, jobs, much of her health, a husband. Eventually, she swore off booze. She was sincere, and she was desperate, and she never meant anything as much as she meant her promises to stop drinking. But she broke them, again, and again. She tried and tried and regularly told those few who hadn’t abandoned her that this time, she really was going to make it. But she didn’t. Until, finally, despairing and alone, she prayed. She hasn’t had a drink in almost 20 years.

“I believe in salvation,” my friend says. “I kind of have to.”

What’s worse? The laissez-faire ethic of the AT? The reflexive skepticism of the journalist? Or the boundless faith of the sober drunk and the born-again Christian? Is it better to be vigilant, to protect your food bag and your community and your steely-eyed sense of self, or to feed and shelter the hungry stranger, no matter how sketchy? Which is safer? Which is more corrosive to the soul? And why is it that the people who offer the most meaningful answers to the most difficult questions are so often men like Lescoe?

He is on a waiting list for a substance abuse class. He’s got a job in the prison kitchen, and plans to enroll in Bible college while he’s serving time. He has been carving sets of hands in prayer from soap. He spends his time reading Scripture, and watching the black-and-white television he bought with $100 that Nicholls sent him, along with a note comparing Lescoe to Jonah. “The Lord told him to go to Niveah,” Nicholls wrote, “but he went the other way, and you went the other way, too. I forgive you as a brother if you repent for this.”

He especially likes the Sci-Fi Channel and American Movie Classics. “And in the mornings there’s all kinds of gospel on. Believer’s Voice of Victory with Kenneth Copeland. That’s part of my morning praise and worship.”

He wants to live a religious life when he gets out. He wants to stay away from drugs and alcohol. He has always wanted to do right, but he has never been able to stop blaming others for his troubles. As much as he seeks forgiveness and understanding, he seems incapable of extending much empathy to others, even those to whom he brought pain.

He is angry at his ex-girlfriend for taking out the Protection From Abuse order against him, says she is “that type of woman, spiteful and vindictive.” He says if Nicholls had answered his calls from the trail, if he had sent him a new pair of socks, maybe he never would have been forced to commit the crimes he did. He says he doesn’t remember walking into Wanda Clance’s home without knocking a few days before his arrest, or warning her about strangers. Not only does he not remember, he says, but “it hurts me that she remembers that.”

He’d like to finish the AT as a free man. He’s already walked at least most of the way from New York to Georgia. It was a special place for him, a safe place for a long time. It was a glorious, primitive path and a kind of leafy, sun-dappled, mosquito-infested, hilly heaven. For a few glorious late-summer weeks, he felt peace there.

He says he envies people who are on the trail now. Some, he pities. All of them he views with his odd, maddening fusion of piety and self-absorption.

“If you can’t feel God’s presence out there,” he says, “well, then. I feel sorry for you.”