The Story of Enid Michael, Yosemite's First Female Naturalist

'Photo by: National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection'

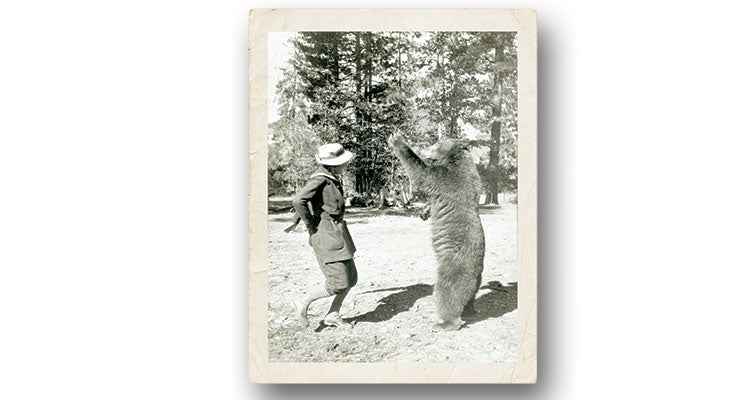

It looks for all the world like the lady and the bear are dancing. In the famous photograph, sepia-toned and marbled with age, she has her arms tucked behind her, knees bent, and legs frozen in a jig. The bear, tall as she is on its hind legs, reaches an arm forward as though about to bow and offer the lady a paw.

There’s an easiness to the scene, a looseness you can read in her posture. It is the look of a woman comfortable in her surroundings, which was Yosemite National Park circa 1920. The lady is Enid Michael, the park system’s first female ranger-naturalist, who, through charisma, passion, and a formidable will, helped define the early years of Yosemite.

She was a school teacher and was always outdoorsy, a fixture on Sierra Club hikes, where she met her husband Charles in the early 1900s. Charles, then the assistant postmaster of the fledgling Yosemite National Park, and Enid took up permanent residence in the park in May 1919. Enid was 36; her life was about to begin.

There are lots of stories of people finding themselves in the parks, the combination of freedom and open space acting like an incubator for things people didn’t know were inside them. So it was for Enid. It didn’t hurt that history was on her side.

Yosemite’s military heritage had fostered a male-dominated administration, with few positions traditionally available for women. But in the early-1900s, bolstered by growing attendance, the park began expanding its interpretive programs and, for the first time, allowed women to run them. Enid accepted a seasonal position, despite having no formal training in botany.

She was nearly 40 by the time she discovered this freedom. The park kindled something in her. The rules were different here, the wall between want and reality as scalable as the valley’s walls. It was what she’d been waiting for. She got right to work. Over 20 seasons, she catalogued more than 1,000 wildflower species and wrote more than 500 articles on Yosemite’s flora and fauna, a still-unrivaled output that makes her the park’s single-most prolific author.

She built her job into a lifestyle, championing a project to build a wildflower garden behind Yosemite Museum, and leading popular hikes and bird-watching expeditions that became tourist draws in and of themselves. (In the famous photo, she’s probably giving a program on bears, which, in that era, often included hand-feeding.) When she wasn’t working, she and Charles took to the walls, pioneering new climbing routes. For 11 months of each year, the couple eschewed wooden cabins and lived in an isolated tent on a sandbar near Sentinel Bridge on the valley floor, enjoying unmatched views of Half Dome and Yosemite Falls. They cooked and cleaned in the primitive style. Enid’s daily routine included skinny dips in the Merced River.

She ranged widely across the park, documenting her routes in straightforward, matter-of-fact prose. She wrote breezily of off-trail bushwhacking and treacherous climbs across faces that all but the hardiest climbers would rope up for today.

In June 1925, after pulling herself up nearly 3,500 feet from the bottom of Yosemite Valley to a knife-edge granite jetty on the southern shoulder of Half Dome, Enid, wearing knee-high socks and soft leather shoes, lingered to appreciate the view.

“The end of the Diving Board is thin and far outreaching so that one may have the uncomfortable feeling of being suspended in the air,” she later wrote. And while the Diving Board would go on to become one of Yosemite’s most famously photographed overlooks, Enid estimated that perhaps only 25 climbers had stood in that spot before her. The parks were still wild and new.

Yet even in the heady days of their Yosemite paradise, Enid and Charles sensed change coming. “The air is filled with smoke, dust, and the smell of gasoline,” Charles lamented in 1927. Once more people ventured to the park, he said, “there will be no rest at all for those who like peace and quiet.” Enid worried how visitation would impact the flora and fauna she loved so much.

Charles died of heart failure in 1941, just weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack. This loss, combined with the onset of World War II, brought an abrupt end to Enid’s tenure at Yosemite. From her first season in 1919 to her last in 1942, park attendance had grown from 91,000 yearly visitors to more than half a million. More than 20 years would pass before the park employed another female ranger.

Yosemite has long since grown up without Enid Michael. There are no statues to her. No botanical societies bear her name. Perhaps that’s fitting. Like millions of visitors, she enjoyed Yosemite simply because it was there, because all she needed to be happy were rocks and trails and the sun reflecting off the river at dawn. Any hiker who goes today will surely know the feeling.