The Top 5 Coastal Hikes in the U.S. for Breathtaking Views

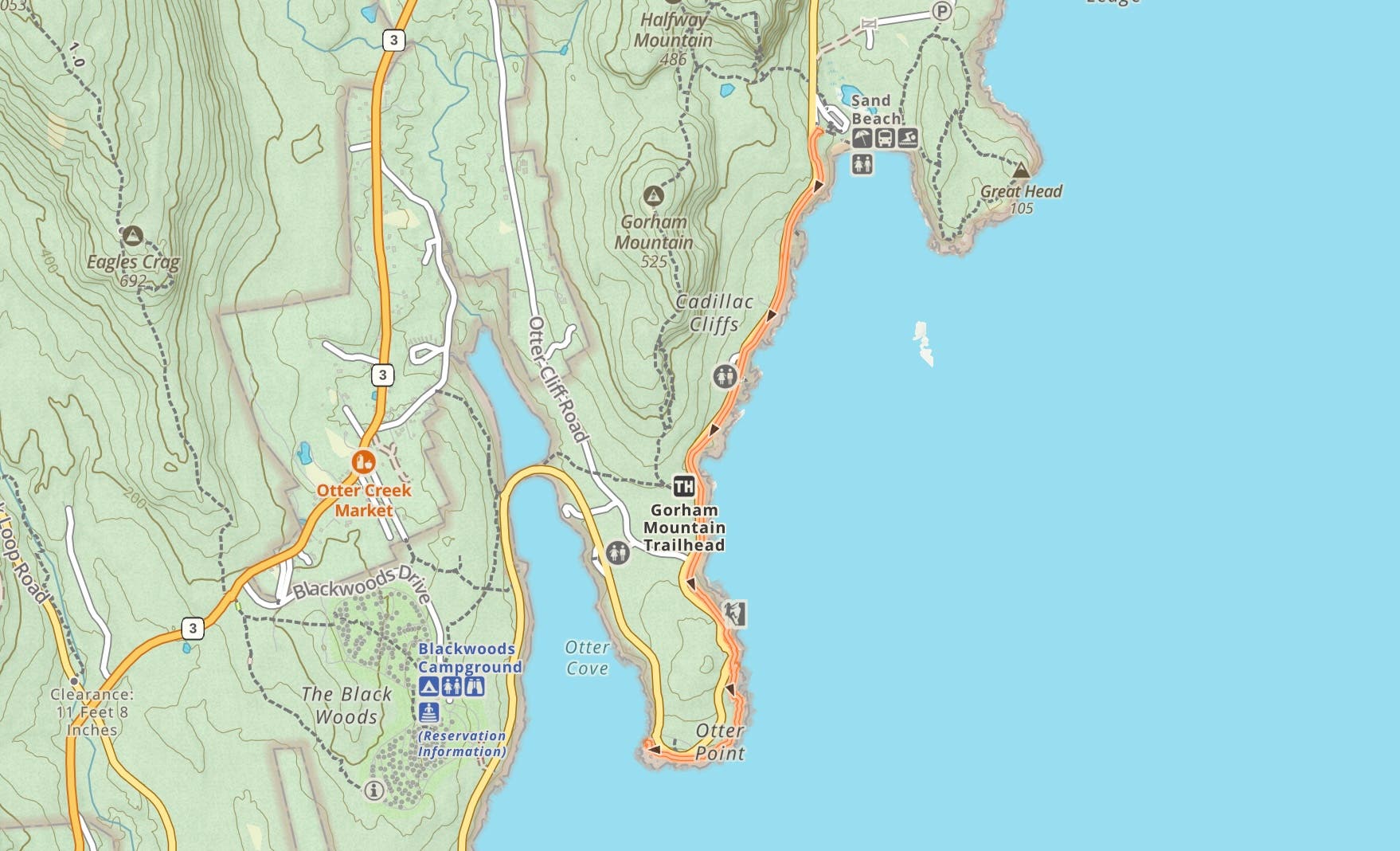

Ocean Path Trail, Acadia National Park (Photo: Douglas Rissing / iStock via Getty)

Humanity has been fascinated by the ocean for about as long as we’ve been around. The roar of the waves, the fury of a marine squall, the strange and enormous creatures that live in the deep—whether it’s curiosity, fear, or just the magnetic pull of seaside relaxation, we can’t keep ourselves away. Indulge your yearning for an oceanside getaway on these five hikes.

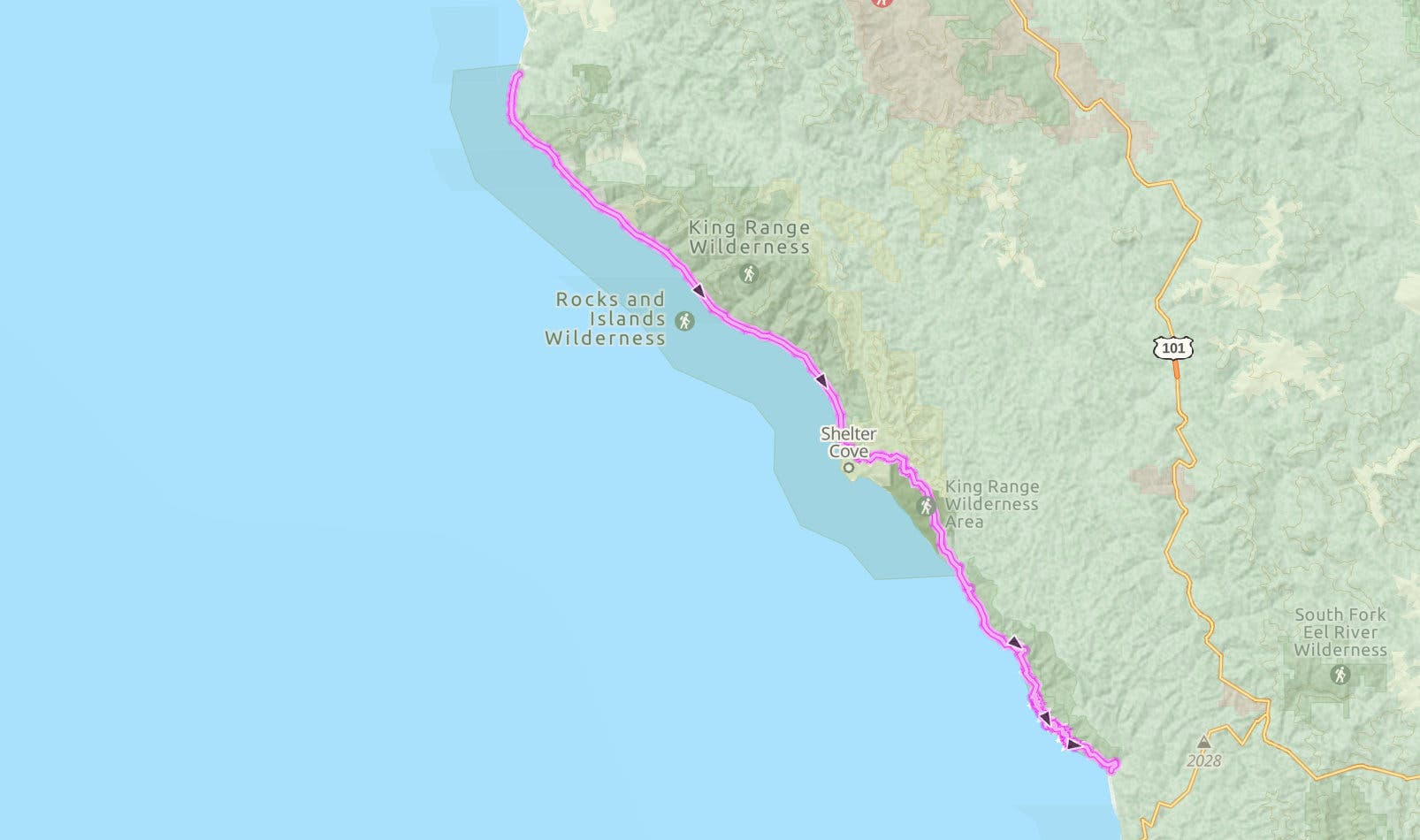

Lost Coast Trail, California

Traveling through some of the last wild coast left in California, the 53-mile Lost Coast Trail follows the edge of the Pacific Ocean past sea lion colonies, sandy beaches, and waterfalls that drop straight to the sea. The same difficult terrain that saved this stretch of land from development makes it a challenging hike, but you’ll be so busy gaping at the scenery that you’ll barely notice the exertion.

It isn’t just beaches and sea cliffs that you’ll find on the Lost Coast, though. The southern half of the trail heads to another iconic Northern California ecosystem: redwood forest. Whether you pick part of the trail to spend a weekend on or do the whole thing in one go, you’ll find something to love on this route.

Share the Trail

The Lost Coast is home to a whole host of critters, from ticks to peregrine falcons to black bears. Make sure you give the larger mammals their distance, especially bears and sea lions. Peregrine falcons and ravens love the rising thermals off the cliffs of the Kings Range; keep an eye out above to spot a passing raptor. Black bears frequent several of the campsites along the trail, and bear canisters are required for backpackers on the northern section. Ticks are especially common on the second half of the trail; long sleeves, long pants tucked into socks, and thorough body checks are the best way to ward them off.

The Trail

The 24.6-mile northern section of the trail sticks to the coast. Start from the trailhead at Mattole; The trail winds through dune grass until mile 2.5, when the defunct but scenic Punta Gorda lighthouse comes into view. Tidepools speckle this part of the trail; take a slight detour to look for anemones, hermit crabs, and barnacles. At mile 5.4 some larger wildlife waits at Sea Lion Gulch, a favorite hangout for sea lions and seals. Soon after you’ll reach a perfect first-night camp site, Cooksie Creek, at mile 6.8.

The next day, head onto a narrow strip of beach beneath sheer gray cliffs (this section of the trail is only hikeable at low tide, so make sure to consult your tide table before heading out). The Randall Creek campsite at mile 8.8 marks the end of the tidal section, but pushing on to Spanish Creek at mile 9 lets you take a snack break among bright orange California poppies. Pitch camp number 2 a few miles farther on at Big Flats (mile 17.1). Deer, black bears, and even bobcats frequent this meadow, so make sure your food is well stored. Finish the section at Black Sands Beach.

To link up with the southern half of the trail, take Beach Road to Shelter Cove Road to Chemise Mountain Road, where you can access the Hidden Valley Trailhead. Finish off the first night of this section at one of several campgrounds near Needle Rock, around mile 9. On day 2, head up into moss-hung redwoods and firs, then drop back down 7.5 miles later at Wheeler Beach, an isolated black sand cove with a scattering of scenic (though windy) campsites. The next section of the hike heads back into the woods for 3.7 miles, then drops into a grove of old-growth redwoods at Little Jackass Creek. Head up and over a couple forested ridgelines for 7.2 miles before heading back to the water at Usal Beach, where the trail ends.

Tahkenitch Dunes, Siuslaw National Forest, Oregon

Fancy waking up to the sound of lapping waves and the cries of gulls and cormorants? This trail may be for you. You’ll start under enormous spruces and sword ferns before emerging onto a sandy beach on this 6-mile loop. The hike to your tent site is only 4.4 miles, leaving plenty of time to wander the tideline in search of shells, storm-tossed driftwood larger than most of the trees you hiked through on your way in, and the occasional stranded jellyfish. It isn’t only marine wildlife you can spot on this hike either: The woods are filled with almost a dozen different salamander species, including the squirrel-sized giant coastal salamander.

Oregon’s coast is a popular destination for surfers, cyclists, and hikers, but that popularity means it’s rare to get a beach to yourself. The short hike to this backcountry spot, though, nets you a private stretch of sand right on the water. Less people means more wildlife, too: shorebirds can often be found feeding and nesting by the dunes, and during migration season you might even spot a gray whale.

Spot This: Brandt’s Cormorant

One of three cormorant species commonly found on the Oregon Coast, the Brandt’s cormorant is easily identifiable by its bright blue throat during breeding season (March to July). They nest on headlands and rocky areas above the beaches. Like other cormorants, they don’t have waterproof feathers, which allows them to dive for fish more easily due to low buoyancy. Other shorebird species commonly spotted on Oregon beaches include the tufted puffin, which nests on a few small islands along the coast; Cassin’s auklet, which digs burrow nests up to six feet deep; and the marbled murrelet, which has a nesting site so unusual for a shorebird—coastal old-growth conifers—that scientists didn’t find a single nest until 1974.

The Trail

Start from the Tahkenitch Dunes Trailhead, Turn right at the first intersection at mile .3 to stay on the Tahkenitch Dunes Trail. At mile 1.3, emerge onto the beach and reach a second intersection; go south on the Tahkenitch Creek Trail. At mile 4.2, turn left at the intersection with the Threemile Lake Trail. The campsite is .2 miles later in a stand of trees atop one of the dunes. A short trail leads from camp to the beach, where you can wander until sunset (always an impressive site on the west coast). Follow the trail along Threemile Lake to a junction at mile 6.6, then turn right to return to the trailhead.

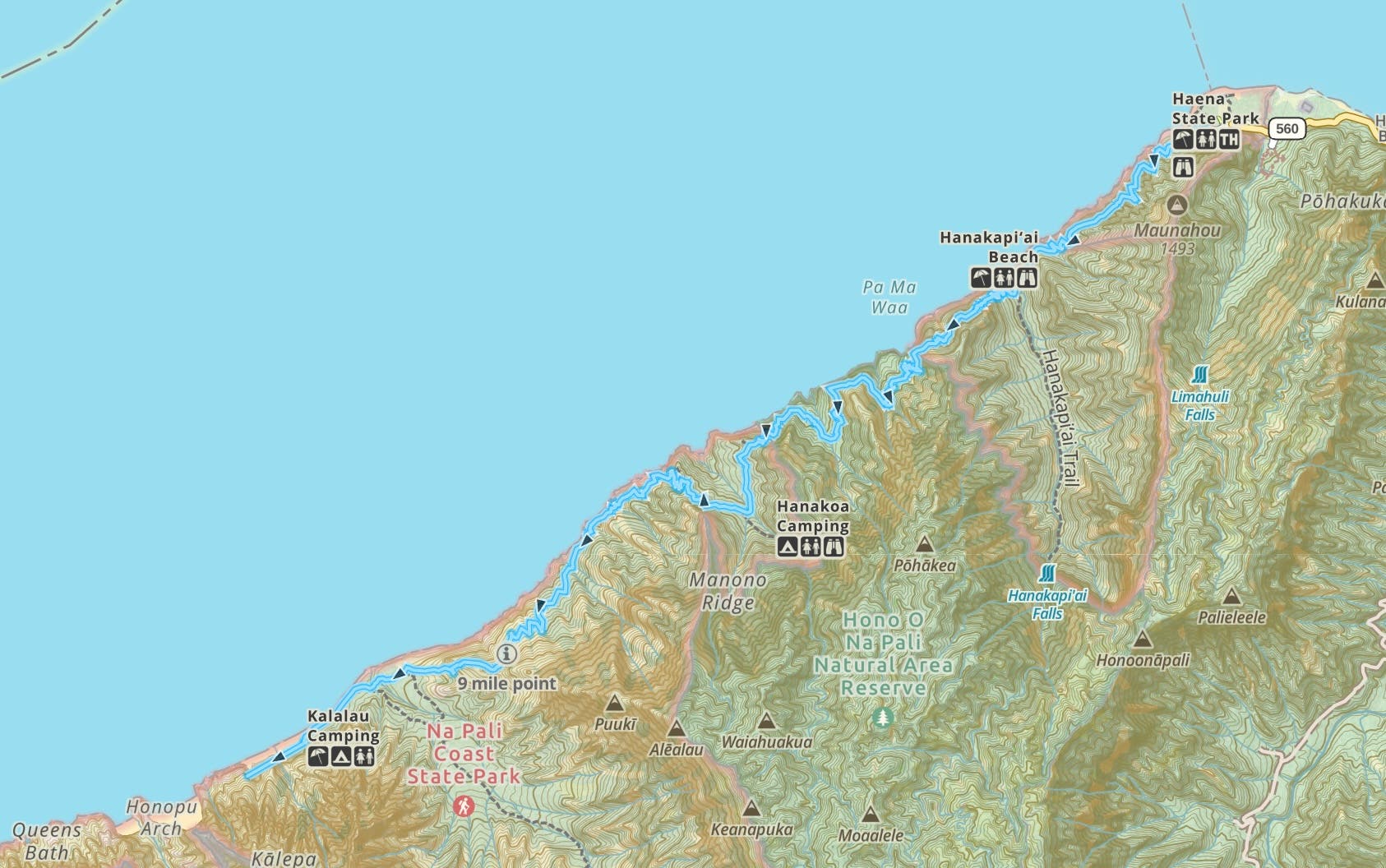

Kalalau Beach, Hawaii

The permits for this stretch of coastline are hard to get, but the experience is remarkable: vertiginous jungle-clad cliffs plunging straight into the tropical sea, perfect crescent beaches, and long-abandoned coffee plantations now growing wild, all to the accompaniment of rolling surf. This trail is the only way to access Hawaii’s Nāpali coast from the land, and offers everything from short day hikes to multi-day backpacking trips where you can explore spur trails up into the narrow valleys. Nāpali is a popular spot for helicopter and other airborne tours (and for good reason: seen from above or out to sea, the spiny mountains look out of this world), but going on foot is the only way to really experience the feel of the place—the jungle, the damp earth, the precipitous cliffsides.

There’s more to this landscape than just natural beauty, though. The Nāpali coast is culturally significant to native Hawaiians, so take care to be a respectful visitor, especially when visiting archaeological sites in the spur valleys off the Kalalau trail. The village sites were once important trading centers for the native people of the islands, who arrived by canoe to trade goods and produce up and down the coast. Stone walls for terraced fields where locals cultivated taro and other foods can still be found in many of the valleys on the Nāpali coast.

Adrenaline Rush

Hope you’re not afraid of heights: At mile 7 of the Kalalau Trail is a spot called “Crawler’s Ledge”. The trail narrows onto a cliff traverse over an 800-foot drop to the ocean, where those who don’t like to be high above the sea might find themselves using the section’s namesake technique. The cliff the ledge is carved from is solid basalt, and extremely solid, but that doesn’t always help when you’re staring down an abyss. Not up for facing that particular fear this summer? Hanakapi’ai Beach and 300 foot Hanakapi’ai falls are both before the ledge, and just as scenic as the later sections of trail.

The Trail

Start from the Kalalau Trailhead at Ke’e Beach. Head immediately into tropical forest, climbing to views of the entire Nāpali coast at mile 1’s 500-foot high point before dropping to Hanakapi’ai Beach at mile 2. You can turn around here for an easy dayhike, or head up a 2-mile spur trail to 300 foot Hanakapi’ai Falls. There are four stream crossings on the way but the rocks tend to be extremely slippery, so pack shoes that can get wet. Cross back and forth between inland forest and exposed oceanside cliff until mile 11, when the trail drops to the campsites at Kalalau Beach. From your oceanside base camp you can backtrack .5 mile along the main trail to a spur up Kalalau Valley, which holds a former settlement and its re-wilding taro fields as well as natural waterslides and enormous mango trees.

False Cape, False Cape State Park, VA

White sand beaches that seem to go on forever, tents pitched right on the beach, the Atlantic rolling in a few feet away. No, it’s not the Caribbean; it’s Virginia. False Cape State Park is only accessible by foot, bike, or paddle craft, giving it a quiet and tranquil feel that’s hard to match in any coast in the Lower 48. One of the last remaining undeveloped stretches on the American east coast, this park is home to ibises, red foxes, and in May, loggerhead turtles laying eggs on some of the six miles of beach. Connect the Little Island, Dike, Sand Ridge, and False Cape Landing trails for a 13.4-mile weekend overnight.

Though wildlife are now the only permanent residents of False Cape, signs still remain of former human habitation. The abandoned town of Wash Woods is now part of the state park. Abandoned in the early twentieth century due to a combination of flooding, hurricane damage, and new legislation prohibiting hunting of the area’s migratory birds, it remained a lifesaving station for shipwrecked sailors until the 1950s.

Graveyard of the Atlantic

The extreme weather that eventually drove out the Wash Woods settlers contributed to this section of coast’s reputation as the “graveyard of the Atlantic”. Harsh weather, difficult to navigate shoals and sand banks, and rough seas have combined to sink over 5,000 ships here since the 1500s. Wash Woods was originally settled by shipwreck survivors, who built their homes from lumber washed ashore from yet another shipwreck. It wasn’t always nature at fault, though: During World War 2, German u-boats would sit just offshore along this stretch of coast and take out ships silhouetted against the lights of onshore cities.

The Trail

Start from the Little Island trailhead. Follow a spit 1.6 miles south beside the water, then veer inland at an obvious opening between the dunes. Pick up the Dike Trail (east trail or west trail depending on what’s closed for migratory birds, which come through in the thousands every summer and winter) and follow it 3.2 miles to False Cape State Park trailhead. Pick up the Sand Ridge Trail for 1.3 miles, heading into coastal marshes that form prime habitat for migrating songbirds and shorebirds like the whimbrel (which nests in the Canadian arctic) and the threatened piping plover. Next, take the False Cape Landing Trail until the junction for the campsites. On windy days you can camp in a stand of live oaks, but most days the best place to pitch your tent is right on the beach. From camp you can retrace your steps to the False Cape Landing Trail and go 1.7 miles south to the abandoned town of Wash Woods. The next day, head back to the trailhead.

Ocean Path Trail, Acadia National Park, ME

At just 4 miles round trip, this dayhike is the shortest jaunt on this list. But what it lacks in length, it makes up for in scenery, packing the granite coastline Acadia is famous for into a path that you can easily take your family and friends along on, too, no matter their age or hiking experience. The precipitous rock formations run right down to the water in most spots, with evergreen forest crowding right to the cliff’s edge. A few spur trails detour to gravelly beaches, where you can wade into the Atlantic or go hunting for shore crabs among the pebbles. The highlight, though, is the end of the trail at Otter Point, where you can poke through tidepools and watch the sunset over the water.

Tidepooling, like the rest of this trail, is great for all ages: The sense of discovery when you find an anemone or a crab doesn’t fade with age, and getting to know more of the science behind the unique intertidal ecosystem only enhances the experience.

Feed the Barnacles

If you wait long enough by a tidepool, you’ll see what looks like a feathery fan emerge from each barnacle in the water. That’s actually the animal’s foot, and they use it to filter plankton and other food particles out of the water. Early in their life cycle barnacles have a planktonic stage, drifting through the ocean with the currents. As they near maturity they find a place to secure themselves—most often a rock or piling, but sometimes a whale or other slow-moving marine animal—and attach their head to the surface, then build their shell around themselves. There are plenty of other critters to spot in these pools, too: mussels, periwinkles (a type of snail), and another type of snail called a dog whelk. The whelks are actually carnivorous, and often eat barnacles and baby mussels.

The Trail

This is a popular trail, so it’s best to arrive early. Start from Sand Beach Parking Lot, less than half a mile south of the park entrance. Head up the stairs above Sand Beach, where the trail itself starts. Pass several small beaches (you can take use-trails down to most of them), then reach Otter Point at mile 2. This is where the trail officially ends, and is also a great spot for tidepooling, photo ops, and watching the sunset before heading back to your car.