Over The Edge

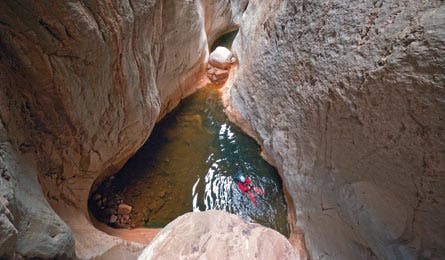

'(Photo by: Dan Ransom)'

(Photo by: Dan Ransom)

(Photo by: Dan Ransom)

(Photo by: Dan Ransom)

(Photo by: Dan Ransom)

(Photo by: Dan Ransom)

Rich Rudow has never been trapped in a slot canyon. He’s never had a partner die in one, either. Which should offer some comfort as I watch him construct an anchor by wrapping a rock with a sling, then stuffing it into a water-filled crack at the lip of a 60-foot drop. But it doesn’t. The foot-long chockstone wobbles in its niche as Rudow carefully lowers his full weight onto the sling. I can’t help but remember the last loose rock I tied myself to, during a climb in the Swiss Alps: It exploded from the cliff, and I felt lucky to survive the fall with only two broken feet. As I dangled under a rescue helicopter en route to the hospital, I vowed never to trust another loose rock. But now here I am, eight months later, about to do just that.

Falling is only the most immediate of my concerns. The winter light is fading fast, and we don’t know if we can get through this unnamed and unexplored slot in the Grand Canyon even if the anchor holds. We entered the limestone crack a half hour earlier, at 4:30 p.m., and found a string of glittering pools filling the canyon bottom. At the initial drop, Rudow rappelled 100 feet into waist-deep water. Then he waded to the far side and lowered himself into another pool. At the distant end of the third water crossing, he was about to drop out of sight when he yelled up. “Hey guys, when the rope goes slack, bring the 120-footer down. But don’t pull this one until we know for sure it will go!”

Will it go? Will we be able to descend all the way to the canyon’s exit? The question echoed inside my helmet as I took my own plunge over the first edge. Rudow, who has spent more than 450 nights in the Grand Canyon exploring secret slots like this, has learned to study maps very, very carefully to judge how much rope to bring on a first descent. But the map tells you only the length of the canyon and the elevation of the entrance and exit. What lies between is always a mystery. We know this sharply cut fracture drops a total of 500 feet through the Redwall formation, but we don’t know if the elevation loss comes in a series of stair steps, allowing us to rappel it in stages, or if we’ll encounter a cliff that exceeds our longest rope, a 250-footer. What if it doesn’t reach?

Sliding down that first rappel, I was mesmerized by the glassy smoothness of the limestone, the gem-like quality of the pools, the 100-foot walls squeezing to just five feet wide at the bottom. And struck by the absolute impossibility of climbing back out once we pulled the rope. I could almost feel the quality of the air change as I descended, like the oxygen molecules themselves were buzzing with nervous energy. Good thing I didn’t know, until later, that Rudow himself was experiencing a rare moment of “high anxiety” as we descended into this unknown slot so late on a February day.

When I reached Rudow, he wrapped that chunk of rock to make an anchor for the next rappel. He tested the chockstone, and despite the wobbling it looked like it would hold. I supplied what canyoneers call a “meat backup” (his rope was hooked to me as well, so I could use my body to stop his fall if the anchor failed), then Rudow belly-slid over the edge. He rappelled to a pool, where he disconnected from the rope while treading water, then swam to the edge and continued downcanyon.

A few minutes later, I suppress my misgivings—the anchor held for Rudow—and follow him down the rope. Every yard I descend chips away at my anxiety, but I don’t dawdle. After I complete my own open-water disconnect, I’m left alone, jogging in place to stay warm in my wetsuit. Steep, smooth cliffs pinch the sky above, while sculpted bowls hold water still silty brown from the most recent flood. For the first time, I can stop concentrating on doing and start seeing, and it hits me that only Rudow and I have ever passed these polished gray and coarser red walls. The rock comes alive as I marvel that we’re the first humans to enter this slice in the Grand Canyon’s Redwall formation. Ironically, we’ve dubbed this remarkable canyon Plan B, because it was our second choice for the day. Which is why we’re in such a precarious position at twilight. Looking up, I notice that the sky is growing darker by the minute. Dusk is settling with winter speed. And we still don’t know if it goes. Then I hear a shout from below.

It’s Rudow, yelling from somewhere out of sight. “Tell Sonny to pull the rope!”

I’m the messenger between Rudow and Sonny Lawrence, who holds our lifeline to safety if the route ahead proves impassable. I hesitate for a moment, then shout the instructions up to Lawrence. He severs our connection with the rim.

While no one expects to get trapped in a canyon on this month-long expedition, no one expects it to be easy, either. The previous night at the campfire, when Rudow had announced the looming 4 a.m. coffee call, a collective groan arose from the darkness. Rudow fired back his standard response, which had become a running joke: “Didn’t you get the memo?”

It had been a long memo, sent to a lucky few. And it pulled no punches when it came to the type of expedition Rudow, 46, was planning. It would be no beer-fueled joyride down the Colorado River. For Rudow’s trip, the floating basecamp would simply provide access to the myriad undiscovered slots that lie in a remote no-man’s land between river and rim. We would launch in early February; water bottles would freeze at night. Most days, the crew would climb as much as 3,000 vertical feet through some of Grand Canyon’s most forbidding terrain, hike a few miles across the desert, then drop into a crack in the earth. And as the infamous memo spelled out: “We’ll set up camp and cook dinner in the dark. It will be cold and miserable at times. There will be suffering … Please bail out if this doesn’t sound like your cup of tea.”

No one bailed. We had been invited to make history. And we’d do it in the heart of one of the country’s most popular national parks. The Park Service estimates that 180 million people have visited Grand Canyon since it was established in 1919, exactly 50 years after John Wesley Powell made his pioneering descent of the Colorado River. But despite the rafting and hiker traffic that has followed, no one has ever seen what’s inside many of Grand Canyon’s innermost recesses. Powell himself anticipated this when he wrote in 1874, “You cannot see the Grand Canyon in one view, as if it were a changeless spectacle from which a curtain might be lifted, but to see it you have to toil from month to month through its labyrinths.”

Few have risen to the challenge, and of those who have, only Rudow and his main partner in exploration, Todd Martin, have focused their energy so obsessively on penetrating the park’s secret world of slots. Approaching these hidden canyons from the rim requires long and arduous hikes, mostly off-trail, to reach a single one. That slowed Rudow’s quest to explore them, but then he hit on the idea to approach from the river. With a month of raft-and-rappel travel, he planned to make a record number of first descents for one trip.

“This was a chance of a lifetime,” says Lawrence, a 58-year-old veteran canyoneer from Redlands, California, without any fear of overstatement. Sixteen people—the maximum allowed on a rafting permit—signed up before Rudow even knew the dates.

On February 5 last year, the group gathered at the Lee’s Ferry put-in. The expedition included legendary figures within the tight-knit community of canyoneers—including Tom Jones. The 54-year-old owner of Imlay Canyon Gear and author of Zion: Canyoneering is simply known as The Emperor to canyon aficionados. On his website, he sums up the pursuit like this: “We go down canyons. And find out what is there. And have fabulous adventures. We use ropes, often. Our hands and feet, quite a bit. Our shoulders, elbows, hips, thighs, calves, backsides—also quite a bit. Our cleverness, our wit, our fortitude, our sense of humor, our pluck, our desperation, our relationships with one another, our spirit of adventure—all these at times, we use.”

The team also includes Dale Diulus, 51, who was Rudow’s first Grand Canyon hiking partner. They met in the 1980s, when Rudow was what Diulus describes as a “long-haired, motorcycle-riding, rock- and metal-music-loving young man” who had just married Diulus’s sister. Their backpacking trips went increasingly off-trail and finally down a few canyons, where Rudow discovered his calling. His first slot was Rider Canyon in 1998, which required some aggressive scrambling, but no ropes. Then came longer, steeper drops. “Pretty quickly we were doing short rappels and my wife got very uncomfortable with our trips,” Rudow remembers. “She bought us rock climbing lessons because she was convinced that we had no idea what we were doing.”

Rudow learned how to handle a rope, but he says the technical challenges weren’t what motivated him. “I didn’t really care if rappels were involved or not,” he says. “I was—and still am—fascinated with the beautiful microenvironments and the sense of accomplishment that comes from getting to a place that few people—if any—have seen before.”

In 2006, Rudow met Todd Martin, then 42, who was already an accomplished canyoneer. Martin and Rudow together became the Lewis and Clark of slots in the Grand Canyon. Martin, an engineer and guidebook writer, is tall, thin, and too introverted to join our crew. Rudow, by contrast, is almost short, a fireplug of muscle, and so unabashedly extroverted that he leads our expedition like a benevolently demanding CEO (indeed, he runs Trimble Outdoors, a GPS technology company in Phoenix).

As of last year, at the start of the expedition, Rudow and Martin had descended 117 canyons in the park—about half of them first descents—with another 80 on their ever-growing to-do list. What remains has never been seen. Even Google Earth can’t offer a hint of what lies below the rim. There’s only one way to discover what’s inside one of these narrow gorges: Go in, and hope you can find your way out.

Rudow may downplay the technical side of canyoneering, but you won’t survive long in sheer, wet, slick, cold canyons without becoming an expert at improvising protection. I’m amazed—and ultimately impressed—by what he and his crew do on vertical rock. I’ve been climbing mountains for half a century, and have notched first ascents from the Alps to Tibet, but none of my alpine travels fully prepared me for this. When I first joined the expedition, their ropehandling immediately put me on the exciting edge of trust.

We were on the rim of a slot we dubbed Plan A, because on the topo map it looked long, skinny, and deep—all the earmarks of a five-star slot. Of the two options that day, it was the consensus first choice. The canyon split the ground in front of us, but it was so narrow we couldn’t peer into the blackness until we stood at the rim—and even then we couldn’t see the bottom.

Instinctively, I looked around for an anchor, something from which we could rappel down the first 50-foot drop, but I didn’t see anything that looked safe. Then Lawrence picked up a rock the size of a kiwi. He wrapped a piece of sling around it, and jammed it in a crack. This makeshift chockstone was our rappel anchor. Most climbers would be horrified—I’ve used knots and pebbles like this in desperation, but never as a first choice. Lawrence tested the protection. It failed. But he repositioned the rock, and this time it held.

We dropped one by one into a waist-deep pool. But after the initial water, boulders and broken rocks littered the canyon floor. Soon we discovered why: A massive chockstone blocked the canyon, preventing flash floods from flushing the debris to produce the polished, marble-like floors that make the best slots so elegant. We bypassed this chockstone with a short rappel, hoping to find clean rock below. But smooth stone and reflective pools came few and far between. Mostly we hiked on rubble sandwiched between sheer but unremarkable limestone walls. We imagined greatness. We only got pretty.

But real exploration has no guarantees—especially when it comes to these unknown slots. Sometimes you discover cathedrals painted cherry and gold by sunlight bouncing off limestone walls, with glittering pools overhung by magical rock formations. At those moments, it feels like fairy dust opens the stone as you go. Other times? Well, a canyon can look tantalizing on paper but turn out to be just scrub and dust. True exploration, as John Wesley Powell surely knew, includes the boring as well as the beautiful.

Unfortunately, Plan A yielded more of the former than the latter. At the exit, wetsuits came off and the mood took a downward turn. It was hard not to bemoan the unrewarded effort. On an earlier, similar hump, Aaron Locander, 32, from Phoenix, at least found some dark humor in the struggle. “I don’t actually like canyoneering,” he’d drawled sardonically, his large waterproof camera system thumping against his chest as he stepped over chaparral. “My true passion is carrying scuba gear through the desert.” Now, he remained silent. The others talked of dinner and sleep.

There was good reason to call it a day. It was already late on a winter’s short afternoon (and we’d been up since 4 a.m.). But still, I gave voice to my private hope: “What about Plan B? Maybe that’s the good one. Rich, do you think we could squeeze it in before dark?”

“Probably not before dark,” said Rudow, “but we can find out!” Four of us wanted to give chase. The rest of the group returned to camp.

Which is how Rudow, Lawrence, Todd Seliga, and I end up attempting a first descent through Plan B, with night falling, relaying messages to each other about when—and if—to pull the rope. Ten minutes after I call up to Lawrence, instructing him to pull our lifeline to the rim, he and Seliga join me and we follow Rudow in the gathering darkness.

We reach a point where the trickling stream plunges over an overhang. In the darkness we can’t see the bottom, but Rudow estimates it’s less than 250 feet—the length of our longest rope—to the talus. But he’s still anxious. “It was wet and cold, we didn’t have bivy gear, and I’ve never rappelled out at night,” he says later. “I didn’t want to get trapped.” Rudow rigs an anchor, this time with a webbing knot jammed into a half-inch-wide crack. This knot will be the anchor for our free-hanging rappel, along with a backup knot-in-a-crack a few feet higher. I want yet another backup. I don’t get one, but at least we tie a line to the rappel rope so three of us can be meat anchors while Rudow tests the system. He goes over the edge. The knots hold.

When it’s my turn for the free rappel, I spin in space. My headlamp stabs first the wall, then reflects off splashing water, then vanishes into the black void. For the first few seconds, I can only think about those knots-for-anchors, my life hanging literally by a thread. But my trust builds the longer I hang there and spin. These guys are real pros, and I’m slowly gaining confidence in their unconventional techniques. As the cycle repeats, I watch the rock come and go. It’s rhythmic, like breathing. I’m reminded of what Rudow calls these secret passages: airways in the Grand Canyon’s lungs.

And something else Rudow said hits me in a new way. As he’s become more skilled at finding and navigating these canyons, he’s been able to focus on the real rewards and less on the technical dangers. As he descends, he says, he mostly just thinks, What’s around the next corner? It sounds simple, but it’s really a sign of true exploration—the kind Powell did almost 150 years ago. And that’s exceedingly rare these days. I’ve pioneered new alpine routes, but mountains can’t hide from cartographers, satellites, and binoculars. Go online, and you can print out a pretty good topo to nearly everywhere on the planet—even zoom in for remarkable photographic details of remote corners of Tibet. Twenty-first-century climbers know the route. The only question is if their ability and gear will get them up it. This is different. This is traveling uncharted terrain. And when a canyon goes—when we come out the other side—we’ve added new territory to the known world.

Over the following two days, we move camp downstream toward the next set of slots on Rudow’s list. After bouncing down thunderous Lava Falls—no spills—it’s party time. Rudow shows up at the riverside celebration in a pink bodysuit and is dubbed Canyonman. The festive atmosphere isn’t just for running the rapids. Lava also marks a transition point where the Colorado River emerges from its constrictive canyon and opens into a broad desert valley. The warming spring air magnifies the sense of openness.

But the change also signals the coming end. We’ve notched 19 slots in 21 days. There are only three virgin canyons left on Rudow’s list. After finding another dud in Indian Creek, the day after running Lava, it’s hard not to wonder if the best is behind us.

It sure feels that way at one of the last camps, which looks like a scene from Apocalypse Now. Sightseers’ helicopters swarm from the Hualapai Indian Reservation on the south shore of the river. Away from the arid, buzzed-over campsite, the mood improves; after all, this is the Grand Canyon. But the ravine ahead is wide, gravel-bottomed, dry, and hot. Rudow has targeted a sister canyon to this one just a few hundred yards over. How different can it be?

Nobody knows, of course, which is why Rudow is compelled to look into every one. The Grand Canyon’s sandstone and limestone layers evolve in unpredictable ways. Rather than eroding into V-shaped valleys as typically occurs elsewhere, sometimes the layers—mostly the limestone ones—crack open. Water scrapes away at the bottom, which dissolves straight downward, leaving vertical walls on both sides.

At the Redwall rim, the earth splits and the group emits a collective Whooee! The feeling intensifies when water appears; it’s only a trickle, but flowing water almost always indicates good things to come. The squeaky sound of rubber wetsuits stretching over skin mixes with the gentle background tinkling of dripping water. Coral light reflects off the rock walls.

Lori Curry is first to go inside. Though the 54-year-old from Las Vegas is one of the most active canyoneers in Nevada, she’s not been out in front much on this trip. Now she’s eager to scout a few downclimbs and raps. But after only two twists in the canyon, she stops to wait, frozen by the remarkable sights. Water has polished the floor glassy smooth, with a 20-foot-wide channel dotted with reflecting pools. Light glows in the marbled hallway, painting the rock silver and gold, then shades from apricot to ocher. A sliver of blue marks the sky above. A few turns of the canyon farther, the walls transform to a brilliant blood-orange and a spring burbles through green and black stripes of moss.

Then it’s Rudow’s turn to stop in his tracks, also gobsmacked. “You will not believe what this canyon does next!” he calls back. The slot bends back on itself in a 270-degree twist—dubbed the Corkscrew Room. A 20-foot drop leads out of the Corkscrew and into a chest-deep pool. Then comes a sinuous stone floor so clean you could eat off it. Rudow says it’s one of the longest continuous Redwall slots he’s ever seen. “It’s unique in the Grand Canyon,” he says. “It has big, graceful lines, subway-like tubes, hallways, and colors that run from silver to lime. On a scale of one to five stars, this is definitely a six!”

Fittingly, the crew names it Climax. Needless to say, it goes.

It’s easy to imagine returning home now, the quest fulfilled, the treasure found. But after sampling just a few of these hidden slots—and seeing Rudow’s very long to-do list—I realize that the Grand Canyon’s innermost secrets may never be fully discovered. And we should all be grateful for that. The real prize, I’ve learned, is standing at the edge of the unknown.

Editor’s note: Rudow went on a repeat expedition in spring 2012. He returned just days before press time, and says, “We got in two more first descents and scouted two new must-do canyons.”

DIY Slots

Todd Martin, author of the new Grand Canyoneering: Exploring the Rugged Gorges and Secret Slots of the Grand Canyon ($30, toddshikingguide.com), recommends these routes to suit a range of skills, time, and fitness. Avoid all slot canyons when flash flood conditions exist. Permits required for all camping in the park (nps.gov/grca).

1) Havasu Creek “From Havasu’s famous waterfalls, experienced hikers can brave the chain-assisted sections and follow the aquamarine stream all the way to the Colorado River.” Stats: Strenuous, 3 days, 36 miles, easy navigation. ACA (American Canyoneering Association) rating: 1C VI*

2) Tuckup Canyon “One of the best long slots in the park that’s completely non-technical, though there are some moderately challenging climbs to get up and down a few boulders and pour-offs. The canyon features several natural arches and a particularly pretty section of Muav limestone narrows.” Stats: Strenuous, 2-4 days, about 30 miles depending on the route, moderate navigation. ACA rating: 3B V-VI

3) 150-Mile Canyon “This is the longest and most scenic Redwall slot in my book. Come prepared for wading or swimming in cold water (wetsuits recommended), short rappels, and fixing ropes on the way down. Rope jugging and challenging climbs are required on the return.” Stats: Strenuous, 2-4 days, 13.5 miles, moderate navigation. ACA rating: 3B VI

4) Garden Creek “This gem is hidden right next to the most popular trail in the park. The canyon is technical, featuring rappels to 200 feet, and it requires a mid-wall rope transfer to descend a stunning horsetail falls. Bring wetsuits.” Stats: Strenuous, 1-2 days, 13.5 miles, easy navigation. ACA rating: 4C IV-V

Note The first descents mentioned in the story were discovered after Martin published his guide.

*The ACA rating categorizes technical difficulty, water hazards, overall risk, and time commitment. See canyoneering.net/docs/ratings.pdf for details.