National Parks: Capitol Reef

Slickrock traverse in Capitol Reef National Park (Kim Phillips)

Waterpocket Fold’s sliced up sandstone (Kim Phillips)

View of the Henry Mountains (Kim Phillips)

Slickrock bowl in Capitol Reef (Kim Phillips)

Henry Mountains form the backdrop to this route (Kim Phillips)

I thought the rope would solve my problem, but as can happen with ropes, it only led me deeper into trouble. I was trying to extend an unproven route through Capitol Reef, solo, and the rope had enabled me to descend one more rotten cliff band. But rigging an anchor in loose boulders had eaten up time. Now I was standing on an isolated sandstone fin that protruded out over a yawning canyon, with no way forward. Dead-ended again.

Fortunately, I’d long since learned that getting stymied in the Waterpocket Fold was never a true failure. I knew that finding which routes didn’t work would eventually help me zero in on ones that did. And I’d discovered yet another site to put on my personal, expanding map of Capitol Reef. The table-flat mezzanine that had thwarted me was easily the most spectacular campsite I’d ever stumbled across. To my east was a poster view of the snow-capped Henry Mountains, risinglike abandoned pyramids. To the west, 1,000-foot cliffs of blonde sandstone slammed in close, their walls like overlapping El Capitans, interweaving to pinch off the gorge’s headwaters. But I had no overnight gear, my water was long gone, and the late October temperature was quickly skydiving from warm to frigid. So as sunset dimmed toward darkness, I dug my headlamp out, rigged my ascenders, and began the long, black retreat toward home with a bittersweet pang of regret. I had not succeeded, but I had not failed. I’d punched the route a few more miles. And I’d be back.

It was a cold January in 1990 when I decided, on the spot, to make Capitol Reef National Park my backyard. A friend and I had backpacked into the deep, ochre cleft of Spring Canyon, post-holing down the sandstone gorge through month-old snow that didn’t have a single footprint. We camped in a narrow sandstone hallway underneath a corkscrew pinnacle that reared defiantly overhead like it was giving the finger to the gods of erosion. We tucked deep into our bags as the stars came out and the canyon became a sandstone freezer. Around midnight, I crawled out of the tent into a scene painted by glowing moonlight, so still my heartbeat sounded like war drums.

I’d visited Capitol Reef before, in warmer seasons, and been staggered by the audacious geology of the Waterpocket Fold, a brick-red Wingate escarpment topped by whimsical cones of blonde Navajo sandstone. But it wasn’t slickrock scenery alone that compelled me to move to the nearby hamlet of Torrey. Capitol Reef is special in other ways. There are only a handful of developed trails. Most of the landmarks remain unnamed. The roadside attractions are so-so. The wildest topography lies concealed, accessible only by tough foot travel. In order to find Capitol Reef’s best places, you have to follow your curiosity through crisscrossed gullies, over anonymous slickrock saddles, and across crumbling boulder fields. You almost never reach your goal on the first try. My kind of place.

I spent untold hours running along sandy washes and countless days scrambling through the deep, meandering canyons of my new backyard, often returning by the dim glow of a headlamp. Atop the tortured geology of the Waterpocket Fold, in this place Ute Indians named “land of the sleeping rainbow,” I discovered tans and oranges and shades of vermilion I’d never seen before. And I found my own personal paradise.

The routefinding was more complex than anything I’d ever encountered. Gorges pinched off into dead-ends or died in pouroffs. Cliff bands hid between the contour lines of topo maps. Even aerial photos didn’t have enough detail to resolve the maze of crag and canyon, ledge and gully. Simple out-and-back hikes often turned into mini epics. I learned to rely on obscure signposts like odd-shaped trees and individual boulders. Each trip felt so much more personal, and wild, than it would if I were following signed trails. I reveled in the childlike joys of real exploration. And the more I probed, the more I wanted to find a route through the northern Waterpocket Fold’s soaring domes and faulted canyons—in one side, out the other, witnessing all the geologic mysteries that lay in between.

Capitol Reef is a long, linear park, running 100 miles north to south from the badlands of Cathedral Valley to the narrow canyons of Halls Creek and the Muley Twists. In the south, it’s defined by a long, narrow series of tilted sandstone flatirons, in places less than a mile across. But I was always drawn to the northern reaches, where the Fold is thicker, twisted and broken into a jumble of weathered sandstone peaks crisscrossed by knife-straight faults. It’s a dense desert mountain range, much of it impassable—unless you like to climb dangerously soft rock with zero protection. Slowly, I became obsessed with finding safe ways through the forbidding maze.

Had others done so before me? Maybe. Slickrock country is, after all, the kingdom of hermits, and people here treasure their supposed secrets to an amusing degree. But the more I advanced, the more I came to believe that maybe no one had ever wandered exactly here. There were no local legends, no mapped routes, no desert rat beta, no cairns or paths or even broken branches. The only prints I ever saw were cougar, coyote, and deer, later joined by desert bighorn sheep once they were reintroduced in 1996. Even now, 20 years later, I’ve never seen another hiker off-trail.

I became acutely aware of the consequences of a misstep, while alone, out in some obscure side canyon. Rocks roll, ledges crumble, branches break. I took to hauling bivouac gear, even on short jaunts and trail runs. While most places get tamer over time, Capitol Reef just got bigger and badder.

The first time I actually tried thru-hiking the 17-mile section across the Fold, between Capitol Gorge and Grand Wash, was in 1994, with four friends. We were all lifelong outdoor pros, but we only made it nine miles in three days before retreating down narrow ledges and sketchy sandstone slabs, headlamp batteries dying, tails between our legs. The next year, I managed to pull it off with a pair of New Zealanders, though certainly not by the best way. We spent most of our time in overgrown gullies, and used a rope repeatedly. The success left me surprisingly unfulfilled. It was an inelegant and risky route, stupid even. I wanted a more scenic, less technical path, with room to wander.

That search eventually turned into a 10-year, stop-and-go effort. Once GPS units and desktop mapping improved, I could explore and later see exactly where I had been, and how that related to neighboring peaks or gullies. It soon became clear I wasn’t looking for a single route, but a braided series of possibilities, weaving the best threads together into an original fabric.

With this revelation, it became less about finding a way through and more about finding hidden gems within. A ponderosa-ringed pothole here, a gymnasium-size slickrock bowl there, a pool of tadpoles, a vertigo-inducing overlook, or a bighorn trail through ancient, fragile cryptobiotic soil. I finally put all the links together and completed the point-to-point journey on a 2005 solo. But by then I knew I wasn’t done. The finish line changes. I’m still working on extending the route farther north and south, finding ever better campsites, imaginative detours, and hidden passes.

The best part? After all those years of exploration, I’m sharing my secret hideaway—yes, including all of that hard-earned GPS data—with you. But make no mistake: Even when you know the way, this backcountry demands respect. I’ve completed the traverse half a dozen times, and I still have to bail when conditions are bad, or improvise detours because of ice-slickened rock or flood-caused changes.

Of course, I want you to exercise good LNT etiquette, but I’m not too worried about newcomers messing up my backyard. Most of the route is on slickrock or sandy wash. With a little smarts, you can travel the entire way leaving literally no mark. Stay off the cryptobiotic soil, and follow game trails when you must cross small patches. Don’t build fires because they’re illegal. And don’t leave cairns or campsite rock piles because that spoils the adventure for the rest of us.

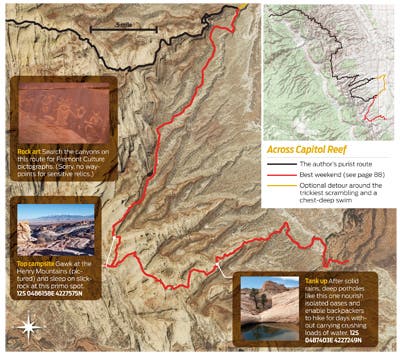

So come see why Capitol Reef is the national park system’s best-kept secret. Or better yet, discover your own private paradise here or in any other wilderness. I’ve found equally remarkable pockets of wild terrain in some of America’s busiest parks—deserted passes in Yosemite, vacant slickrock plateaus in Zion, secret rhododendron-lined swimming holes in Great Smoky Mountains. You can do the same: Just develop the skills and confidence to get off the trail, and forge your own route. Capitol Reef has taught me that anyone can discover a whole new level of adventure, wonder, and commitment simply by looking at a pass, a ridge, or a blank spot on the trail map, and wondering, “Can I get to the other side…?” Do it Author Steve Howe crafted this ideal 32-mile thru-hike (with a recommended detour around the trickiest section). Allow about five days. Start with the hike through Spring Canyon, and camp downstream from the spring. When you hit UT 24, turn left and go .3 mile to Grand Wash. After 1.8 miles through this canyon, arrive at an unmarked wash heading south. Here, you’ll begin 16 miles of off-trail hiking and scrambling, crossing the headwaters of 11 unnamed canyons.

TRIP PLANNER

Trailhead/start From the park visitor center, drive west on UT 24 for 3 miles to Chimney Rock trailhead.

Shuttle/end From the park visitor center, drive 9 miles east on UT 24, then turn south on Notom Rd. Continue 6.2 miles (road becomes dirt). Turn east at 5560 South/Pleasant Creek Diversion Rd. Go 1.6 miles and park in a turnoff overlooking Pleasant Creek.

Permits Free; pick up at the visitor center’s Backcountry desk.

Water You need carrying capacity for 2 gallons per person in warm weather and a filter to treat sometimes murky water. Our GPS track includes waypoints for potholes that are typically reliable, but sources can come and go.

Cautions Expect scrambling, difficult routefinding, and uncertain water sources. Never trust the rocks, which are loose. Cell reception is nil in the backcountry, so don’t count on a speedy rescue.

Key gear High-cut boots or ankle gaiters to repel grit; trekking poles; water shoes or sandals; 40-foot rope for pack hauling.

Season Spring is popular for wildflower seekers. Late September and early October see far fewer visitors, calm blue skies, and gold cottonwoods. Summer highs reach the 90s.

Maps USGS 7.5-minute topos: Twin Rocks, Fruita, Golden Throne, and Notom ($8 each, store.usgs.gov)

Info (435) 425-4111; nps.gov/care

Trip data Get a complete tracklog at backpacker.com/hikes/reef

BEST DAYHIKE: SPRING CANYON

You don’t need to tackle Capitol Reef’s hardest terrain to see some of its best scenery. This 10-mile, cathedral-like hallway combines easy canyon hiking and foolproof routefinding (there’s only one way to go) with life-list sights, like lush cottonwoods backdropped by massive sandstone amphitheaters. From the Chimney Rock trailhead, good trail leads into the deep cleft of Chimney Rock Canyon. At mile 2.9 you intersect Spring Canyon and hang a right, leaving the maintained path behind. In a mile, the wash drops through a slot canyon. Explore it until an abrupt, sketchy downclimb; detour around on a trail along the left/north rim of the narrows. The wash-bottom route continues past overhanging cliffs to a spring with good water at mile 6.5. Continue beneath towering cottonwoods until you ford the Fremont River (usually knee to thigh deep) and pop out on UT 24. Leave a shuttle car here, or you can hitch or bike the seven-mile return west to the trailhead (but cyclists must finish with a steep, three-mile hill climb). Trip ID1073088

BEST WEEKEND: CAPITOL GORGE TO PLEASANT CREEK

campsites sit in the broad slickrock bowls between Capitol Gorge and Pleasant Creek. Exploring this country requires routefinding southward from the eastern park boundary in lower Capitol Gorge, up along anonymous piñon-juniper ridgelines, and past superb viewpoints of the Waterpocket Fold’s amazing geology. There’s no trail, but it’s a relatively short distance, with no hazards (if you encounter any technical terrain, you’re off route). After just two miles, break out onto naked slickrock, where you can wander almost at will, searching for flat tent sites, small ponderosa groves, and clear-water potholes. It’s easy to follow the stony saddles southward. Most highpoints offer superb vistas along the Reef, or southeast toward the distant Henry Mountains. Take extra food. You won’t want to leave. Find our favorite site here: 12S 0486158E 4227575N. Download the tracklog at backpacker.com/hikes/1079393.

KEY SKILL: HAUL YOUR PACK

Most of the scrambling on this thru-hike is straightforward for confident, experienced hikers. But you’ll still likely hit a few places where you’ll feel safer climbing without a heavy, water-laden pack, which can throw you off balance. Err on the side of caution: Remove your pack and haul it up (bring a 40-foot rope). First, empty the side and shove-it pockets, as any hard objects stowed there will cause significant fabric abrasion when scraped across rock. Likewise, repack hard items like fuel canisters and pots, so their hard edges won’t cause the same thing to happen to the pack bag. Next, tie one end of the rope to your pack’s haul strap (add a backup loop as well, but avoid dragging it by key hip or shoulder straps). Use a bowline knot*, which is easy to untie after being loaded by the pack’s weight. Now pull it straight up the fall line. (Learn more at backpacker.com/knots.)

*Tie a Bowline: The rope’s long end is the “tree” the loop is the “rabbit hole” and the rope’s short end is the “rabbit”. Make the rabbit jump out of the hole, go around the tree, and dive down the hole.