Glacier's Gladiator: Harvey Locke's Glacier National Park Mission

'The Flathead Valley (Garth Lenz)'

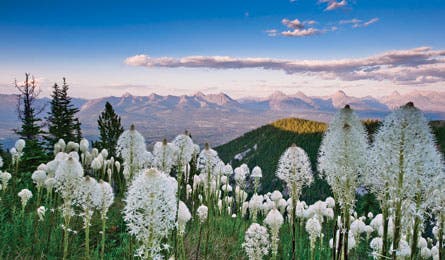

The Flathead Valley (Garth Lenz)

Locke with ILC photographers in 2009. (Garth Lenz)

Glacier National Park celebrates its 100th anniversary this summer, and festivities will be a lot more, well, festive thanks to the efforts of Harvey Locke. Until early this year, it seemed quite possible that a proposed coal-mining project in the Flathead River Valley, which lies north of the park in the Canadian Rockies, would spoil the party. The 78-mile Flathead River flows down the western boundary of Glacier, and proposed mining upstream threatened to dirty the park’s water and damage the 560-square-mile ecosystem that keeps Glacier’s wildlife so vibrant.

The story might have unfolded like so many before–big mining company (Cline) gets its way in remote wilderness while local government (British Columbia) rolls over–without Locke’s intervention. The 51-year-old vice president of the Wild Foundation, based in Boulder, Colorado, was hiking on the Continental Divide in 1989 when he first saw the Flathead, a stunning valley adjacent to Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park (formed by Glacier in the south and Waterton in the northeast). “When the open-pit coal mines were proposed, it was like World War I,” Locke says. “Miners and conservationists dug in for a long battle.”

Since then, Locke, who is prone to military analogies, has applied his take-no-prisoners brand of advocacy to saving the Flathead and greater Glacier. “Locke likes to make it very clear that he’s in charge, which can upset some of the independent-minded people whom conservation attracts,” says Casey Brennan, program manager of the British Columbia environmental group Wildsight. “But that’s also what makes the movements he leads effective.” To wit: Locke’s efforts have helped protect 10 million acres in three countries.

Last year, Locke fought Cline’s proposal by organizing a publicity project with the International League of Conservation Photographers. Eight shooters spent two weeks capturing photos–grizzly bears, bull trout, mines–that Locke and the Flathead Wild Coalition used to raise awareness among locals and lobby for wilderness over industry.

That set the dominoes in motion. In January, the United Nations World Heritage Commission reported that any large-scale mining in the Flathead would threaten the Peace Park. On the eve of Vancouver’s Winter Olympics, B.C.’s government announced that mining there was banned. And in April, ConocoPhillips voluntarily retired 170,000 acres of oil and gas leases in Montana’s Flathead Valley.

Locke is leading the next charge, so to speak, this August, when he hikes through Glacier and Waterton with 10 international conservationists. He wants the Flathead added to the Peace Park, with long-term protections against all logging and hunting as well. “We have the momentum,” Locke says. “We hope it’s just a matter of time.”