China: The People's Hiking Revolution

'Nan Ping Village.'

Nan Ping Village.

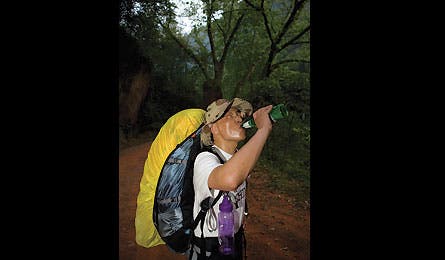

Changhui downs a beer.

Shatuo River campsite.

Hiking behind the Chinese flag.

Peasant-built trails.

Nationalism runs deep.

Hiking through a garden.

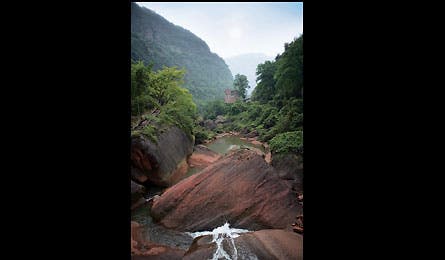

A waterfall on Shatuo River.

Liquor shotguns his first beer at 10:29 a.m.

We’ve been hiking up a steep trail in southwestern China’s Guizhou province, a place that looks a lot like Kentucky with bamboo. Fir, pine, and rhododendron also thrive here, at an elevation of 900 feet and roughly the latitude of Orlando, Florida. But there’s nothing gentle about Guizhou’s chaotic canyon topography–the result of India pushing into Asia, and dozens of rivers cutting through soft sandstone and limestone. Where the hillside isn’t dead vertical, it’s covered with dense, pack-grabbing vegetation. The temperature has climbed into the upper 80s, and the next ridge disappears into white-cotton humidity.

Liquor is a 20-year-old Chinese university student with a protruding stomach and soft, round features. This is his first backpacking trip, and it took only a few minutes on the trail before he questioned the wisdom of packing six cans of beer, especially since he’s also carrying several large bags of fried rice, a jar of pickled chilies, and eight raw eggs. So he pops the tab on a Snow-brand beer, lifts it to his puffy lips, and tilts his head back. After draining the can, he knocks the top off a glass vial of glucose, drinks the syrupy liquid, and tosses the empty container on the ground. It rolls to a stop at the base of a pine tree.

Ultralight and Leave No Trace clearly aren’t part of the program for Liquor and his seven companions, a local group I’ve joined for a five-day trek in Guizhou. But that’s hardly a surprise. It took decades for those ideas to evolve among recreational hikers in the United States. Like American backpackers in the 1960s, China’s new homegrown trekkers have only recently gained middle-class means–money and leisure time–to explore wilderness. And like our forebears, they have a lot to learn by trial and error.

A more pressing question is whether China’s budding outdoor culture will promote a broader conservation ethic sorely lacking in the country today. China’s cities and rivers are famously polluted, its factories contribute to smog and dust that reach American skies, and in 2008 the country surpassed the United States as the world’s leading contributor–in total volume–of new greenhouse gases. I’ve lived in China for nearly a decade and have watched its exploding middle class embrace the trappings of prosperity–imported cars, bigger houses, flat-screen TVs, designer clothes–at a speed that can only make these well-known problems much worse. What’s almost unknown, however, is that its burgeoning back-to-nature movement could change the way Chinese see–and protect–the environment. It was hikers and campers, after all, who ignited America’s own environmental movement.

Will these nature-loving citizens push the country in a new direction, just as cash-hungry masses oiled China’s shift toward capitalism? I had joined Liquor and his companions to find out what was happening at the leading edge of China’s newest cultural revolution. But only one thing was certain after a few steps on the trail: Backpacking in China, like everything else in the country, would be unlike anywhere else in the world.

I live in Beijing, which means I had looked forward to my upcoming trek simply as an opportunity to clear my lungs: Beijing’s air is abysmal–a miasma of sand, dirt, smoke, and car exhaust. My anticipation was also heightened because I’ve racked up some of my all-time favorite adventures in remote parts of China–a trek to Mt. Everest’s eastern basecamp, hikes to secluded Buddhist pilgrimage sites in western China, a long bike ride along the Laotian and Burmese borders–and this exploratory trip promised more of the same.

Guizhou, our destination, has a growing reputation as a hiker’s paradise. Only 3 percent of the Missouri-size province is flat, and it contains probably the highest concentration of waterfalls in China. Guizhou’s forests protect rare mammals, including clouded leopards and snub-nosed monkeys. And while wealthier provinces have unsightly, overbuilt tourist infrastructures, Guizhou sees only a trickle of visitors. So when a Chinese friend introduced me to Guan Hongqing, a 28-year-old interior designer, and Guan mentioned that an informal hiking club he runs was planning the trip, I signed on.

The Tianya Backpackers Club (the name refers to a mythical Chinese paradise) gathers on a May morning in Chongqing, a megacity near the center of China. We meet in a restaurant at the bus and train depot. Guan has an athletic build and moves with quick intensity. He wears a battered baseball cap pulled low over his forehead.

Then come two businessmen, each looking for a break from hectic workdays. Zhou Changhui, a rail-thin man with sharp, angular features, sells stoves to hotels and is the group’s elder at 38. His friend, Xu Junjie, is shorter and bulkier and markets disposable products available in hotel rooms–packages of toothpaste and toothbrushes, combs, slippers, soap, and shampoo. Guan introduces me as a journalist interested in hiking and the environment, and Xu immediately apologizes. He has tried, without success, to convince hotel managers to provide high-quality toothbrushes that guests can buy and take home. Perhaps hoping to deflect future questions, he says, sheepishly, that he knows his work isn’t environmentally friendly.

Liquor’s real name is Chen Xiang. He studies engineering and business management at Chongqing University but prefers traveling. Because his father is a government official, he figures he’ll get a good job regardless of his grades, so when he saw the trip mentioned in an online chat room, he signed up.

The rest of the group works in real estate: Two of them are interior designers, one is in sales, one in advertising, and the last an architect. Together, they represent a cross-section of China’s middle class, a demographic that consists of 100 million people with annual incomes between $5,000 and $15,000. Guan makes $500 a month, enough to share a rented apartment with his brother and indulge his passion for travel and hiking. The architect, 28-year-old Guo Shanchuan, earns almost $900 monthly and is considering buying an apartment. He Xiaoqing, a 30-year-old real estate saleswoman who tells us to call her Little Qing, picked me up at the airport in a new Mazda 6 that cost $33,000.

All of the trekkers except for Guo wear T-shirts printed with the English statement, “Tibet WAS, IS, and ALWAYS will be part of China!” Two months before the trip, violent riots broke out in Lhasa over the issue of Chinese rule in Tibet. Nationalism runs deep among Chinese yuppies, and the shirts appear to be a coordinated effort to send a message to a Western audience. I don’t debate the point. Instead, I ask Liquor how he got his nickname.

“I always bring alcohol when I travel,” he says, his giant aviator sunglasses reflecting a soaring web of elevated highways behind me.

“What did you bring this time?” I ask.

“Beer.”

“How much?”

“Six cans. But it’s not enough.”

We board a new, air-conditioned bus and ride six hours to Jinsha, a town of 3,600 people near the start of our trek. Our plan is to hike through the Chishui Alsophila National Nature Reserve, a wilderness area at the heart of 33,000 acres of protected forests. The reserve includes one of the world’s last pockets of alsophila spinulosa, an endangered fern that has existed for about 100 million years, but when we arrive I don’t see any ferns, just thousands of disposable chopsticks drying on the side of the road.

While Guan looks for a local guide to help us improvise a route, I watch villagers feed sections of bamboo into machines that cut them into smooth, white sticks. A woman bent over one of the contraptions says that a skilled worker can make 8,000 sets each day–enough for a profit of about 21 renminbi (just over $3). I ask if locals hike in the reserve, and she gives me the universal what-kind-of-idiot-are-you look: No one has time to walk in the woods, and if they do take a vacation, most people would rather go to a city.

It’s almost six in the evening when Guan finds our guide, a 56-year-old beekeeper named Luo Zhixia who maintains hives in the nature reserve. Still, we have time to hike to the park entrance, and our little band strides out of town on a quiet dirt road that winds through a canyon. A thin tributary of the Red River gurgles softly beside us. A waterfall tumbles over a cliff, its spray catching the late-day sun.

With packs on our backs and boots on the ground, it strikes me as strange to be traveling with a group of Chinese hikers at all. When I first arrived in China in 1996, few locals hiked. I taught college English in western China’s Sichuan province, and with friends I often trekked in the Min Mountains, a range famous for protecting many of the world’s remaining wild giant pandas. But we rarely met anyone on the trails. As we came back with euphoric stories of clean air and quiet nights, some of our students ventured out. But most returned clutching sore legs and never went back.

So it’s heartening to hear Guo Shanchuan, the architect, talk about his love for the outdoors as we walk through a thick pine forest. Guo has a wiry frame and long bangs that shadow his eyes. When I ask why he hikes, he offers philosophy. “Everyone is essentially good, but in society we’re corrupted by outside influences like money and sex,” he says. “In nature, we can return to a more natural state.”

We reach the park gate in high spirits, full of anticipation for tomorrow’s hike, and we drop our packs in a clearing that looks ideal for a camp. But the mood dampens when a black Volkswagen Santana–the ubiquitous car of Chinese officials–appears from the darkness. Word has spread that a foreigner passed a nearby village, and a park officer examines my passport and says I need official permission to enter the wild heart of the reserve. “There are poisonous snakes and wild boars. It’s not safe,” he says, adding that with the Beijing Olympics three months away, “it would be bad for the nation if a journalist is hurt or lost.” Park management is still evolving in China.

We pitch our tents in a tight cluster like circled wagons; we’ll consider our options over dinner. Good to his name, Liquor finds a local villager willing to sell beer at 45 cents a bottle and we pop off the caps and light butane stoves. Little Qing heats a canister of homemade red-braised pork, the cubes of meat simmered with soy sauce and sugar. Zhou boils bread in milk, a traditional dish in northern China.

We discuss our next move. No one had foreseen a problem since several of Guan’s friends had trekked to the preserve’s inner sanctum a year earlier, and there are typically few restrictions on hiking in protected areas. The cadre’s insistence on getting official permission for me, however, makes things difficult. In China’s top-down infrastructure, low-level bureaucrats rarely take initiative or responsibility. As a result, approval can take days as requests work their way up a chain of command. We don’t have time for that. Guan announces that, in the morning, we’ll hike over the next ridge and into an unrestricted part of the reserve. We crawl into tents after a calming round of Son of Heaven cigarettes.

Mainstream Chinese weren’t always so disconnected from the wilderness. Before World War II, there was a tradition of going to wild places to paint, write, and meditate. But Mao Zedong, Communist China’s first leader, saw nature as a resource. One of Mao’s top-down directives was to open farmland by clearing forests and draining marshes, an order that left much of China barren. Logging across eastern China left only tiny pockets of primary forest. In Hubei province–once the Chinese version of Minnesota with thousands of lakes–the area covered by water decreased by 75 percent.

Mao would be shocked, to say the least, by today’s China. Literally thousands of hiking clubs have sprung up. Two million Chinese climbed Yellow Mountain, the country’s most popular pilgrimage site, last year. A surge in the number of outdoor stores is also telling: In 1996, Chinese hikers bought army surplus tents and prayed it didn’t rain. Today, there are well-stocked outfitters in most Chinese cities.

Before my trip, a friendly employee at Beijing’s Sanfo–an outdoor retail chain that over the last decade has grown from a single back-alley shop to a franchise with 23 outlets–helped me clean my camp stove and showed me how to flip the fuel tank to empty the line and prevent clogs. While I waited for the stove to cool, I looked at a flyer about trips run by an affiliated hiking club. Last year, the group led 35 treks longer than five days, plus 200 day and weekend trips. Dozens of twentysomething and thirtysomething Chinese browsed racks stocked with everything from titanium sporks to The North Face apparel and $2,000 Suunto wrist computers. The quality and selection was high, even on the budget racks. You could outfit a beginner with homegrown brands for only $300, and it’s decent stuff–a testament, perhaps, to what Chinese manufacturers have gleaned from assembling American outdoor products.

China’s park system has kept pace–at least in terms of land acquisition. The amount of protected space in China has doubled since 1995, to 374 million acres. Some parks have begun to maintain short trails. And the central government established the first official national park–Tangwanghe, in the far northeast–in October 2008.

For China’s few longtime hikers, the shift has been dramatic. A few days before I flew to Chongqing, I had coffee with Li Shuping, a former director of the China Mountaineering Association. Li started hiking the way Chinese did everything under Mao: He had studied to be a doctor, was reasonably fit, and in 1975 his work unit assigned him to accompany the government’s second Mt. Everest expedition.

“We were climbing for the glory of the state,” Li, now 62, said between sips of cappuccino. “No one chose to trek then, but now young Chinese have time and money. It’s different. They want to hike.”

Two officials escort us back to Jinsha the next morning, and we hike east on a two-lane road, past a government propaganda poster urging us to “improve the quality of the population” by having few or no children. Before the trip, Guan made us sign a contract that required each member to “possess physical strength, adequate supplies, willpower, a willingness to take orders, and a strong sense of the collective.” Jiang Wei, a 28-year-old advertising designer, makes good on both the second and fifth requirements–and sends another nationalist message–by pulling a Chinese flag from his backpack, tying it to a stick, and carrying it in front of our small brigade.

An hour later, we hike back into the forest on a narrow trail that climbs out of the valley. Small black-and-red birds dart between tall stands of jade-colored bamboo. Alsophila spinulosa, with thick woody trunks and crowns of radiating fronds, poke between spruce and pine trees. Beyond the distinctive ferns, distant ridges collapse into haze.

But Chinese peasants are economical, and the steep path offers few switchbacks–they’ve carved the shortest but hardest route through the forest–and our group soon fragments. Little Qing mops sweat off her forehead and tugs at her tight black jeans. I turn a corner to find Jiang Wei sitting on a limestone outcrop drinking from a vial of brown liquid that I guess is herbal medicine. “It will prevent me from going into a coma,” he says, deadpan.

Zhou, the stove salesman, rounds the bend shouting into his cell phone, “You think you’re busy? I’m even busier!” It’s his first trek, and he bought his gear–including a $60 Lover Ice Rock sleeping bag–a few days earlier. Like most of the group, he packed too much, and now he pays our guide a few renminbi to carry his pack.

“My lungs aren’t good,” he explains. “I smoke and I don’t exercise. I just drive around in my car all day.” Liquor shotguns that first beer.

After a full, hard day on the trail, it’s beginning to feel like a real backpacking trip. The fit hikers charge ahead; the stragglers lag behind. Liquor and I stop to wash our faces in a cool stream tumbling from beneath forest shrubs. I continue up the trail and turn to see Liquor–alone in nature possibly for the first time–sitting on a rock, smiling like a Buddha.

An hour later, we scramble up a steep, overgrown slope in search of a cross-country route into the valley, where a river and waterfall await. But almost as soon as we leave the trail, our guide backtracks to find a better way. By the time he returns, Guan has decided it’s too late to continue.

Instead, we pitch our tents in a farmer’s field. As with many Chinese parks, the boundaries of Chishui Alsophila Reserve were drawn between centuries-old villages, making terraced fields of rice and wheat part of the landscape. Farmhouses with white walls and gray tile roofs sit between towering oaks and carefully tended patches of cabbage and leek. It could be Nepal–without the teahouses and trekking hordes.

That sort of beauty is common to many Chinese villages. But earlier, when I suggested to a farmer that he was lucky to live in such an enchanting place, he shook his head.

“We hope the government builds a road soon,” he said. “Then we can open a hotel.”

His wish, while not entirely unexpected, serves as an abrupt reminder that China’s environmental problems could soon become much, much more severe. While only 2 percent of Americans work on farms, 60 percent of China’s 1.3 billion people live in rural areas–and most of them dream of moving to cities. If China’s ratio approaches the U.S. figure, the environmental impacts will resonate around the world. China already is the world’s top consumer of steel, coal, meat, and grain, and it’s widely considered the world’s largest market for endangered wildlife and illegally logged timber. The conservation group Wild Aid estimates that most of 100 million wild sharks, skates, and rays killed each year end up in Chinese soups. In its most recent annual report, the group states that “all the biological studies, the international treaties, the valiant efforts of the enforcement agencies, the billions of dollars spent on wildlife conservation will be for nothing if we cannot turn off [Chinese] demand.”

The potential environmental costs of China’s development have spurred green groups to aim conservation campaigns at average citizens. Wild Aid has run television ads showing basketball star Yao Ming swearing off shark fin soup. Environmental disasters are also changing views, as happened in the U.S. in the 1960s. When Cleveland’s polluted Cuyahoga River caught fire in 1969, the environmental movement gained some of the momentum that led to passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. China will need more than one Cuyahoga River disaster to reach its tipping point. But that will likely happen. In 2005, an explosion at a chemical factory in northern China spilled 100 tons of carcinogenic benzene into the Songhua River, China’s fourth-longest waterway. In 2007, Lake Tai, China’s third-largest freshwater lake, became so polluted that the government shut off tap water to millions of people.

A groundswell of public anger about the disasters has pushed Beijing to pass more stringent environmental laws. In September 2007, officials declared that 15 percent of China’s energy should come from renewable sources by 2020. Last June, the government enacted a nationwide ban on certain kinds of plastic bags. Real progress, to be sure, but at the local level, where statutes are enforced, officials allow profitable industries to pollute at will.

Most Chinese don’t see a way of bridging the chasm between national laws and local enforcement without the bottom-up controls of a free press, aggressive advocacy groups, and an independent legal system, things the Communist Party has so far not allowed. Before my trip, I asked Zhong Yu, a Beijing-based Greenpeace staffer, if China has an emerging version of David Brower, the fire-and-brimstone Sierra Club president who helped push environmental awareness into the American mainstream. She shook her head. “Our NGOs face too many restrictions. The government doesn’t want us to create ties with other groups, so there isn’t any national coordination.”

“The government isn’t willing to let someone become as influential as Brower,” said Zhong’s friend, Tsering Norbu, a Tibetan who had worked for The Nature Conservancy. “They want to keep control.”

I wake up to crowing roosters and make a cup of coffee as others perform morning rituals. Liquor cracks a raw egg into his mouth. Little Qing picks at a plate of leftover noodles. Guan–not a morning person–swears as Xu Junjie shakes his tent.

The sun has crested the ridge by the time we start hiking. We follow a dirt trail south through a series of small villages and after four miles hit the Shatuo River, another tributary of the Red River. Our progress moves us out of cell phone range, finally silencing Zhou’s frantic sales calls. The only sounds are birdsong and our group’s quiet conversations.

As hikers often do, Guan and I swap stories about trips we’ve taken. I describe a 1998 trek to Mt. Everest’s Kangshung face basecamp. He tells me about a 2007 trip, when he walked for three days between ranger stations in Kekexili, a protected Tibetan wilderness bigger than Maryland.

“It was absolutely desolate, but it was the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen,” he says.

When I ask if he thinks China can protect such landscapes, he shrugs. Even remote scenic areas have been overrun with hotels and restaurants. “There are too many Chinese,” he says simply.

That’s not apparent at the moment, though: We have the trail entirely to ourselves. In the afternoon, Guan finds a wide section of the river wedged between steep cliffs and we pitch our tents on dry, flat rocks. We strip to our underwear and–with schoolboy yawps–jump into a deep pool of clear water. Soon almost everyone is floating and splashing, enjoying the kind of rejuvenating moment that resonates for months after a trip. It’s Liquor’s first time swimming in a river, and he floats in the pool, staring up at the sky.

The others are also, finally, immersed in nature. Xu Junjie finds a blue frog and calls Little Qing to take a picture of it. Zhou checks again to be sure his phone has no signal and puts it away.

“A year ago, I didn’t understand why people would hike,” he says. “Why sleep in a tent and carry so much weight? But in the city it’s all about work and getting somewhere. Here, I’m finally able to relax.”

After dinner, we build a fire by the swirling river. We lie back and admire the wash of stars. Zhu Ying, a 24-year-old advertising writer with a quick smile and short-cropped hair, says she never sees so many stars in Chongqing’s sky. Until a camping trip last year, she hadn’t known there were more than a handful.

Experiences like that–literally discovering nature–have prompted individual Chinese hikers to change their behavior. Guan goes out of his way to recycle batteries; Xu would pay a 30 percent premium for a hybrid car if one was available.

But they’re also realists. “Twenty years ago we didn’t know what a company was,” Xu cautions. “We had never heard of a CEO. All we can do is look at how America got where it is and replicate that path. Once people’s standards of living are high enough, they’ll begin to think about protecting the environment.” The mystery, of course, is how soon that day will come, and if it will be soon enough.

On our final day, we hike farther along the Shatuo River, settling into a comfortable pace with plenty of rest stops. We dip our feet in the water, admire giant black-and-blue butterflies, and catch the spray of a waterfall cascading into a pine forest. On our last night, we camp near Tiger Head village, population 25, and celebrate the end of the trek with a feast. Liquor buys 36 Mountain City beers from a farmer, and Xu purchases and butchers two chickens to stew with vegetables and chilies. We make toasts as a crescent moon rises.

In the morning, we pile into the back of a white pickup. The road out is under construction and there are many potholes, but the group is in good spirits. We sit on our packs and bounce past felled trees and rockslides that score the hills. We sing Taiwanese pop songs and a rolling ballad Guan wrote to the tune of “The Internationale,” the anthem of communist parties worldwide. We pass workers building high-tension power lines, the steel towers rising over a dense section of pine and bamboo, and the Tianya Backpackers Club raises its collective voice over the noise of the truck and the workers.

It isn’t a pretty song, but it’s full of energy.

Beijing-based Craig Simons is the Asia bureau chief for Cox Newspapers.

China’s Top Treks

hike some of the planet’s most spectacular–and undiscovered–terrain.

- Mt. Everest Kangshung Face

See the Big E like few others do on this two-week trek. The route skirts villages, crosses two 17,000-foot passes, and traverses one of the world’s highest-elevation forests. DIY hikers should use Trekking in Tibet: A Traveler’s Guide, by Gary McCue. Beijing’s U-Do Adventure (udoadventure.com) offers guided trips. - Mt. Gongga Circle 24,790-foot Mt. Gongga–with a vertical relief greater than Everest’s–on this 12-day trek in western China’s Sichuan province. It loops around the mountain and crosses three passes, the highest at 15,095 feet, and leads through pristine forests and to remote Buddhist monasteries. The route follows unmarked trails, making guides a must. Wild China (wildchina.com) runs 16-day trips.

- The Great Wall The famous wall is actually a series of walls and towers built across northern China. The best three-day trek is along a section of 500-year-old wall in Shanxi province. The trail begins at Juchangbao, a now-crumbling fortress built by China’s Ming dynasty rulers, and ends at a tower 31 miles west. U-Do Adventure (udoadventure.com) guides this and other Great Wall trips.

- Mt. Khawakarpo This sacred Buddhist pilgrimage in a Tibetan area of Yunnan province crosses an alpine region rarely seen by Westerners. The two-week trek starts by the Mekong River and wraps around 22,241-foot Mt. Khawakarpo, ascending five major passes as it traverses forests inhabited by Asiatic black bears and red pandas. Tibetan-run Khampa Caravan (khampacaravan.com) leads trips.

- Mt. Tai Experience hiking the way locals do: Climb one of the sacred Taoist pilgrimage sites in the east. Yellow Mountain is the most popular among them, but Mt. Tai, in eastern Shandong province, offers better hiking. A 10-mile round-trip passes a dozen temples, ascends a staircase with 6,660 steps, and encompasses several hotels and restaurants on top. Info: travelshandong.us/taishan.htm