Canyon Confidential: Utah's Grand Gulch

'Hikers ascend slickrock benches in Grand Gulch.'

Hikers ascend slickrock benches in Grand Gulch.

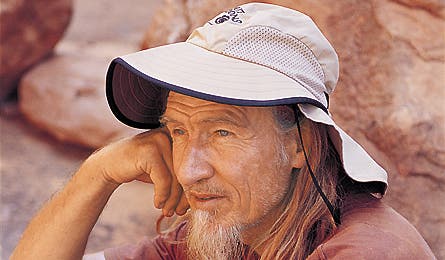

Guide Vaughn Hadenfelt in a moment of repose.

Floating the slow and easy San Juan River.

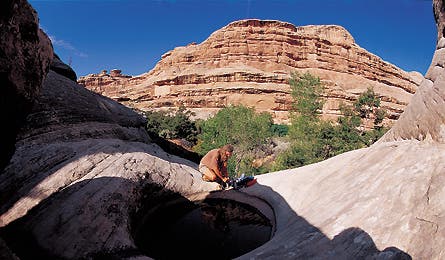

Vaughn pumps water from a pothole.

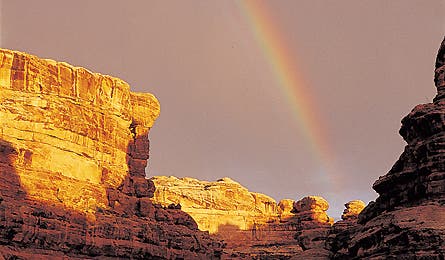

A rainbow emerges over Grand Gulch.

700-year-old Puebloan ruins.

Kim Brandeau follows the trail through Shaw Arch.

Hikers follow the dry creekbed to a bend in the canyon.

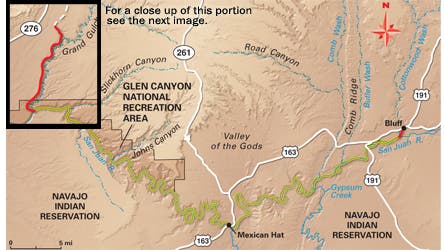

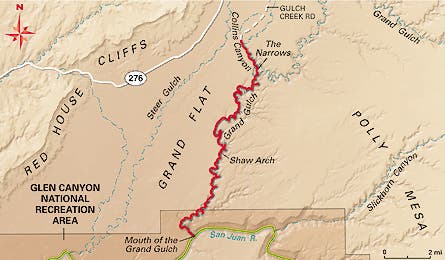

Map by International Mapping Associates

May by International Mapping Associates

It’s a sunburned September day in southeast Utah, and I’m following 10 parched hikers through a jumble of burnished boulders and sparsely spaced cottonwood trees on the floor of a sinuous canyon called Grand Gulch. Amber-tinted sunbeams filter into the 700-foot-deep chasm and light up our lanky, long-haired, bird-legged backpacking guide, Vaughn Hadenfeldt. He’s hunting for potable water, but the only pools we’ve found so far are a speckled latte brown. “A flash flood ripped through here two weeks ago,” he tells us, “and these pools still aren’t settled. If we don’t find one that is, we’ll be pickin’ grit out of our teeth all night.”

Flash floods tear through this spot a couple of times a year here in Grand Gulch Primitive Area, a 37,580-acre maze of protected canyons 30 crow miles from Bluff, Utah. Most hikers enter the 52-mile Gulch from the top of the canyon, via a handful of trailheads off UT 261, but our group of three women and eight men, a mix of lawyers, medicos, a retired sociology professor, and an environmental engineer, started walking at the mouth of Grand Gulch. This is the farthest point from those trailheads and the least visited section. Our crew was just halfway through a journey that would rank as my favorite in years of exploring empty corners of the Southwest.

We got to the mouth via a five-day, 65-mile raft trip down the lazy San Juan River, a journey worth doing in its own right. This morning, we beached our rafts (river guides would take the boats downstream and out) and hoisted our packs to follow Vaughn, who owns a guide company called Far Out Expeditions. Over the next five days, we’d hike north 40 miles to Collins Canyon through the Gulch’s winding chasms, where at almost every turn lie the homes, tools, and art of the ancient Anasazi, or Ancestral Puebloans, as scientists now call them. This canyon is thought to be the most densely populated area in the pre-European United States. Like the majority of my hiking partners, I’m here because I’ve become an archaeology junkie. After three decades of scaling Himalayan peaks, I’ve traded frozen summits for canyon secrets. And I’ve quickly learned that–when it comes to timeworn red-rock terrain filled with ancient petroglyphs, cliff dwellings, and artifacts–Grand Gulch is the Southwest’s Everest.

Vaughn predicted we’d find good water in Shangri-La Canyon, and 20 minutes later, we catch up to him pumping clear liquid out of a natural cistern into a nylon bladder. The spring isn’t on maps, and it’d be easy to miss if you didn’t know where to look. We gather around the waterhole and guzzle long, cool, slaking gulps. Vaughn smiles. He doesn’t carry maps, yet every nook of the Gulch is imprinted on his mind like waypoints in a GPS.

A thunderhead rumbles as we begin setting up camp on a level bench a half-mile upstream from the waterhole. Though the storm cell whips up dust devils that spin through a posse of hoodoos on the canyon rim, we get only a tiny spray of cold raindrops, as if from a squirt gun. Even so, we make our camp high: The trees in the streambed wear necklaces of brush around their trunks, signs of the recent flash flood (we’d arrived just after monsoon season). I ask Hadenfeldt if he ever has mixed feelings about taking clients to these occasionally dangerous and always remote and fragile locations.

“I’ve seen these canyons flood in minutes flat, but I always watch the weather and only do trips when conditions are good,” he says, “and I’m not worried about leaving a few boot prints. I enforce strong ethics. No one grabs even a twig as a souvenir. No campfires. We pack out toilet paper. I worry more that if young people stop going to places like this, there’ll be no appreciation for wild lands and their history and no next generation to protect them.” Our conversation ends before he can elaborate, when the thunderhead passes and a rainbow forms across the canyon. Everyone gazes in silence, rapt in one of those ah-ha moments when you know with absolute certainty that you are in the right place at exactly the right time.

We’re five miles into our second day of hiking when Vaughn leads us to another ah-ha phenomenon: a circular stone kiva dug into a sandy bench beneath a cliff. Incredibly, two ladder rails protrude through a hatch in the log-and-adobe roof. I have the unnerving sense that the natives who built it are nearby, somewhere, watching us. It looks like a family walked away from here just yesterday.

I approach with the intention of going inside, but Vaughn vetoes all entry. The incredibly well-preserved structure is too delicate. “Plus, it’s a ceremonial chamber, and under the floor, beneath centuries of blow sand, there’s a hollow shaft called a sipapu, representing the place where humankind emerged from an underworld. You don’t want to fall through the floor into the underworld.” Convinced, we tiptoe around the site, seeing potsherds, corncobs, and quartz flakes from tool knapping. “It’s okay to pick them up and look, or take photos, but put everything back where you find it. Don’t take anything out of context,” Vaughn tells us.

Frankly, it amazes me that anything remains here at all, for the modern history of Grand Gulch is one of plunder. Four cowboy brothers who ranched around Mancos, Colorado, in the 1880s–the Wetherill boys–popularized the Ancestral Puebloan world when they discovered the ruins of Mesa Verde, the now-famous national park that attracts a half-million visitors annually. The trove of artifacts they found there spurred them on a quest into Four Corners’ prehistory, and by the 1890s they were horsepacking along Grand Gulch, digging up artifacts and “mummies,” as they called them. It was an era before archaeological discipline, when digs resembled hasty robberies and the booty was displayed in traveling road shows or sold to museums and collectors. By the time the 1906 Antiquities Act stopped the excavating free-for-all, thousands of artifacts and hundreds of disinterred corpses had been carted out.

In the early evening of our second day, we make camp by Shaw Arch, 11 miles from the river. The path, alternating between sandy streambeds and dusty game trails, leads under the span, opening magically onto a shaded and breezy grove and a spring. Dark red handprints daubed on the walls at head height and corn-grinding slicks atop boulders show that we’re not the first–by a long shot–to find this a good stopping point.

Vaughn dumps his pack, fetches water, and begins preparing hors d’oeuvres. “You know, there’s some controversy about this arch,” he muses while slicing cheese. “It’s named on maps for Merlin Shaw, a Mormon bishop and Boy Scout leader who died in 1963. Shaw’s admirers incorrectly persuaded the USGS that he’d discovered it, but locals have always called it Wetherill, or Grand Arch.” Vaughn petitioned the USGS to change the name, but Shaw Arch stuck. “Somewhere in these cottonwoods I’ve seen a log with an 1894 Richard Wetherill signature on it,” he says. “I doubt he missed seeing the arch.”

The next two days pass in similar fashion, with easy mileage (six to 10 up-canyon miles per day) through otherworldly geography. Side trips take us to more perfect ruins. At midday, when the temperature reaches 100°F and the air feels like hot syrup, we hug the shady canyon flanks. All I can think about is replenishing my water bottles.

Water, or lack of it, probably forced the ancient canyon dwellers out of here. Tree ring analysis of logs from ruins indicates a terrible drought from 1276 to 1299. The pressure on communities must have been extreme: A pot of water could have been worth more than life itself. Indeed, the archaeological record of the final phase of habitation in this canyon suggests warfare and even hints at cannibalism. By 1300, the canyons were empty, the inhabitants having marched south to the Rio Grande. Luckily, with Vaughn’s expertise, we find water in tiny springs and smooth, brine shrimp-filled potholes.

On our fifth and final day, I wake to another clear, cobalt sky framed by orange canyon walls. We haven’t seen another soul, and the only hint of modernity is a set of footprints in the sand. I slurp down a cup of acrid instant coffee, shoulder my pack, and fall into line with the group. Just past The Narrows, where the Gulch constricts to a 20-foot-wide slot, we veer west into Collins Canyon. We slog uphill for the last two miles on an old cattle trail that, at times, is literally chiseled into the canyon wall. A cliff dwelling’s dark and empty doorways look like ghost eyes peering down on us. The wall is covered with images of spear shafts and warriors that seem to guard the remainder of Grand Gulch, which winds ahead to the top of Cedar Mesa. And there’s the infamous line of musical notes india-inked on a cliff; researchers think Richard Wetherill’s wife, Marietta, penned them 110 years ago to mimic a canyon wren’s song.

Near the lip of the canyon, we file through a cave littered with saddle grease tins from the cowpoke era, then hit a 4WD road. Vaughn’s wife, Marcia, waits at the trailhead with the Far Out Expeditions van. She greets every sweat-stained body with a hug and aims us at a cooler packed with soda and Moosehead lager.

We sit on our packs with sighs of relief and knock back a few while looking out at the white caprock dotted with pockets of piñon and juniper. The depths of Grand Gulch vanish beneath the trees like a labyrinth of crevasses beneath a glacier. And I realize that nature’s best gifts are those that lie beneath the surface.

Plan It

Grand Gulch, UT

Season

March through mid-June and September through October are primo. July and August bring monsoons and heat.

Guides Far Out Expeditions (435-672-2294, faroutexpeditions.com) and Wild Rivers Expeditions (800-422-7654, riversandruins.com) team up for this trip annually from September 8-18.

Map

Pack Trails Illustrated #206 Grand Gulch Plateau ($12; natgeomaps.com)

Permits Required ($8/person/trip). Reserve up to 90 days in advance (435-587-1510), and pick them up the day of your trip at Kane Gulch Ranger Station.

Contacts

Call (435) 587-1532 for road, trail, weather, and water conditions.

The Way

From Mexican Hat, take US 163 four miles north to UT 261. Drive 29.4 miles to Kane Gulch Ranger Station.

Online Extras

For more photos and non-guided trip itineraries, go to backpacker.com/grandgulch.