The Time I Almost Lost an Eye on the Appalachian Trail

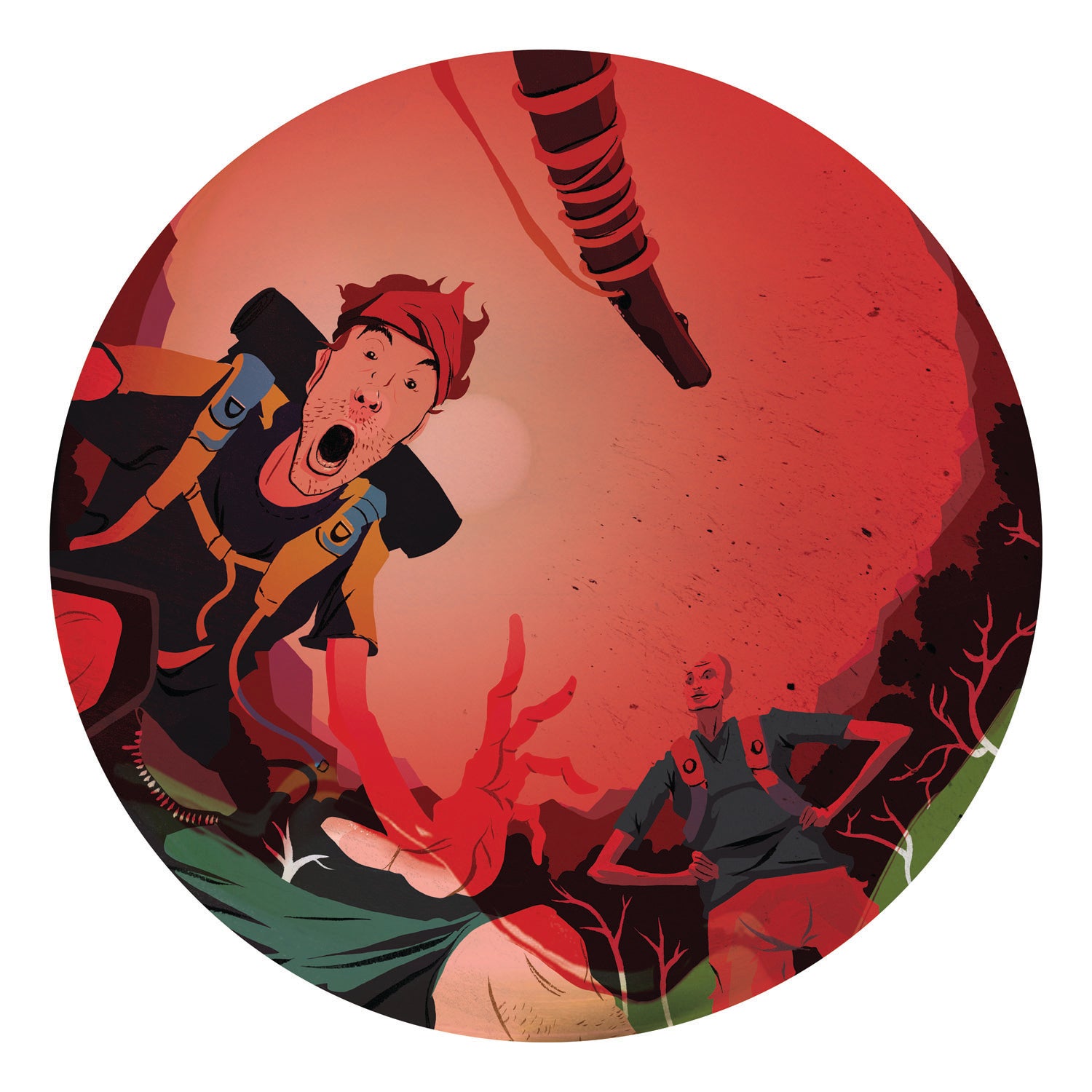

'Illustration by Ryan Garcia'

It was supposed to be a mellow hiatus from the myopic intensity that had defined my southbound thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail. Two buddies were set to join me in Hot Springs, North Carolina. One—whom I’ll call Red—would be with me for a week, the other—whom I’ll call Modern Man—for 12 days.

Neither amigo was in trail shape. Red, though experienced, had been working the previous six months on a boat on the Mississippi River. Modern Man, a self-avowed city boy, had never placed a pack upon his back until we cinched up and made our way uphill out of Hot Springs.

We planned short, leisurely days, which would provide a welcome respite before my final push to Springer Mountain.

As scripted, day one went smoothly. We hiked a mere 8 miles, set up camp early, and relaxed around a campfire while sipping tepid vodka-Tang screwdrivers.

Day two did not go as scripted. When Red and I arrived at Groundhog Creek Shelter, located on a side trail a quarter-mile from the AT proper, we realized Modern Man was not with us.

Since the tread through that section was well worn and well marked, and since there were no trail or road junctions upon which he could have strayed, we could envision no scenario in which Modern Man could have become disoriented—except perhaps as a result of an especially intense reaction to the mind-altering substance we had consumed at lunch. He had simply vanished into thin air.

As darkness approached, Red and I began to consider the possibility that some mishap might have befallen our neophyte pal. Maybe a sprained ankle or snakebite. Or maybe he was sitting on the trail communing with a fern. So we walked back out to the AT and retraced our steps—all the way back to the last spot we remembered seeing Modern Man, some 6 or so miles. No sign of him.

We returned to the shelter, hoping that, by some miracle, our friend would be there. He was not. So, armed with flashlights, we yet again retraced steps we had already retraced, yelling until our voices were raw. It was a surreal experience, not least because our minds were still, um, altered, and the woods were alight with an intense display of firefly pyrotechnics.

Just before dawn, we staggered back to the Groundhog Creek shelter, caught a few restless ZZZs, and pondered our options. There was no other choice but to notify search-and-rescue. The closest road crossing was thankfully in the direction we were going—toward Great Smoky Mountains National Park. And so we headed on, not sure if we were leaving our friend behind, and feeling uneasy about it in any case.

Less than an hour later, we came across Modern Man. He was sitting forlornly under an improvised poncho shelter, his eyes bleary. He had simply walked by the side trail leading to the shelter and hunkered down when he knew he was lost. Such a possibility had not occurred to us.

Though we were weary and glad to be reunited, we had to stay on schedule because both Modern Man and Red had to return home on preordained dates. After agreeing that, henceforth, we would only experiment with hallucinogens after arriving in camp, we began the first serious ascent on our itinerary: directly up the switchback-free side of Snowbird Mountain. Near the summit, while crossing an otherwise innocuous little trickle, I slipped. My head snapped forward and eye came down directly on the pointed end of my chest-high hiking stick. My entire field of view exploded with bright red.

“HELP!!!” I screamed, which was tough, given that I was hyperventilating. When Red arrived, having run when he heard my high-decibel shriek for assistance, he was so winded he could scarcely stand. He saw my bloodied face, yelped, and spent the next few minutes freaking out, which did nothing to calm my nerves.

Modern Man was unruffled. He spoke reassuringly, directed me to tilt my head back, and said something like, “Well, you don’t see that every day.” My eyelid had nearly been torn off. You could pull it down and see the white of my eyeball, which might make for an amusing trick at a Halloween party, but, out in the middle of nowhere, it amounted to a stressful turn of events. Modern Man reattached my eyelid with a couple butterfly bandages improvised from duct tape and pronounced me patched up enough to continue.

For the next few days, whenever we passed other hikers, they would let loose with some variation on the shocked exclamation theme—things like, “OH MY GOD … WHAT THE F*** HAPPENED TO YOUR EYE???”

Red left us at Davenport Gap. He seemed happy to be departing for the relative calm of the Big Muddy.

Near Newfound Gap, a shoulder strap broke on my pack, forcing me to hitchhike into Gatlinburg in search of repair. During this time, I made a detour to a doctor’s office to have my now-oozing eye examined by someone who had perhaps washed his hands in the past week. You know you are in dire straits when a medical practitioner recoils at your appearance. After loading me up with antibiotics, the doctor told me the infection was bad enough that, had I waited another couple days, I would have gone through the rest of my life being a natural for roles in pirate movies.

Back on the trail the next day, we started into Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which is heavily regulated. When AT hikers apply for their permits, they have to specify at which shelters they will be staying. Modern Man and I arrived at our designated destination only to find that we would be bunking with a young couple on their honeymoon. This was awkward, so we hiked on to the next shelter—3 or so miles away—walking into a flash-and-boom thunderstorm that ripped through and soaked us down to our skivvies.

Next morning—the last Modern Man would be with me—we learned from a passing dayhiker that the shelter at which the honeymooning couple was staying had been hit by lightning the previous evening, likely during the same squall that had drenched us. The young wife had been killed. The husband had been paralyzed on one side. He barely survived. It was all over the local news, the dayhiker said.

Before taking his leave, the dayhiker looked at me and asked, “What the f*** happened to your eye?”

At that point, my injury seemed mighty inconsequential.

It is an understatement to say our descent into Fontana Village was somber and reflective. Though the day was beautiful, and though the birds were chirping brightly, there was no way to mentally tamp down thoughts regarding the cruel interface between fate and coincidence.

Modern Man and I drifted apart after that trip, as if the distance might bury the bad memories. And my eye? It took a long time, but it eventually healed. Though sometimes I wonder if that trip caused other lasting effects. I maybe spend more time glancing toward the heavens than I used to, but that’s something that likely comes with age, whether you’re on the trail or not.

M. John Fayhee, one-time editor of the Mountain Gazette and author of 12 books, advocates whittling the ends of trekking sticks until they’re nice and round.