Alone in a Crowd: Hiking Yosemite's North Rim

'Yosemite Falls (Scott Mansfield)'

Yosemite Falls (Scott Mansfield)

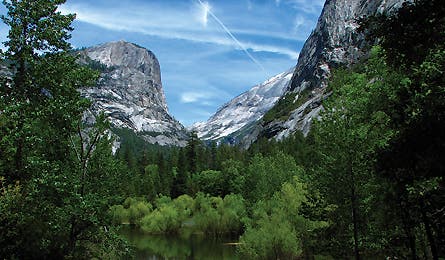

Mt. Watkins (Dave Miller)

Giant boulder slides (Thomas Atkins)

Black bear (Dave Miller)

I’m standing by myself on top of El Capitan with a lump in my throat as big as Half Dome, but heights aren’t my issue: It’s the complete absence of another person. All alone on the most photographed rock face on the planet? Impossible! Even crazier: I hiked here on a Muir-worthy trail that threads through the heart of Yosemite Valley and hasn’t appeared on a map since 1990. I’d always wanted to hike in the Valley, but had avoided joining the legendary throngs: Yosemite attracts 3.6 million visitors annually and sells out of popular backcountry permits from Memorial Day to Labor Day. My boycott would last until I discovered a way to find real solitude–not just smaller crowds. Then I caught wind of a secret trail, an unknown, heart-of-the-valley path that was dropped from park maps almost 20 years ago. It helps that I’m here in October, after the summer rush and before the late-autumn snows. But damned if I didn’t find it: the perfect backpacking adventure–complete with starry skies, staggering views, and crowd-free streamside campsites–smack in the middle of America’s third-busiest national park.

Since I arrived in Yosemite Valley yesterday, I’ve managed to elude the crush of humanity that’s as much a part of this place as its supersize waterfalls and granite monoliths. Each summer some 95 percent of park visitors squeeze into the Valley’s seven square miles–an area that amounts to less than one percent of the park’s total size. That’s 13,571 people per square mile, per day–and about 13,570 more than I like to include in my backcountry adventures. But in two days of hiking I’ve passed just a couple other hikers, and I’ll encounter only a handful more over the next several days. My secrets: a local named Pete Devine, and that invaluable, out-of-date map.

A 25-year resident and outdoor educator with the Yosemite Association, Pete had regaled me with stories of a secret trail known only to a handful of locals. With the flatulent name OBOFRT–for Old Big Oak Flat Road Trail–it isn’t officially a trail at all, but an abandoned road. Once the main tourist route used by travelers coming from the west and dropping into the Valley, the OBOFRT became a secondary byway after the current Big Oak Flat Road was built in 1940. Then, in 1943, rockslides buried portions of the historic road beneath truck-size boulders, and the OBOFRT was retired. Today, occasional patches of asphalt are all that remain of this idyllic, unsigned footpath.

“Even in August, you’ll almost never see a car parked here,” Pete says, as he edges his minivan into a nondescript pullout on the main Valley road. A ranger had scrawled “Rockslides” on our permit as our originating trailhead, but no sign marks the spot where we start our trip. We’re just west of El Cap Meadow, where scores of people are gaping at the climber-dotted monolith. But here–no one. In fact, I’ll see just 12 people on my entire four-day trek, which follows the OBOFRT for 4.5 miles before connecting with the informally named North Rim trail and heading east, past El Cap, Eagle Peak, and Yosemite Falls. Even without our sneaky start leg, though, this version of the North Rim traverse would be life list-caliber: Solitude extends all along the North Rim, except for pockets of people at Yosemite Falls and North Dome, accessed by shorter spur trails from the opposite end. It also helps that most backpackers favor routes that beeline away from the Valley. But hike above the crowds instead of racing away, and you’ll enjoy some of the most epic views in the park.

Pete and I set out on the roadbed late in the afternoon. We revel in its gentle grade (the rest of the trails out of the Valley are elevator shafts) and make good time striding along manzanita-covered hillsides. Berry-studded bear scat is everywhere, indicating Yosemite’s bruins have been gorging themselves before winter puts the kibosh on good eats. Pete smiles as he points to the faint outline of a bear track headed in our direction.

Everything–not just bears–seems to thrill Pete, who possesses a scholar’s curiosity about the entire natural world. But his muscular legs suggest his learning isn’t all logged at a desk: His 6-foot-5-inch figure practically floats over the landslides we encounter, leading the way until we arrive at the hike’s first overlook–a gem of a vista juxtaposing the impossibly sheer faces of Half Dome and El Capitan. “What I love about this view is the way it hides all traces of development,” Pete says, pointing out how campsites, houses, and even the Valley Loop road remain obscured from our vantage point.

Continuing on, we camp near Cascade Creek, still on the OBOFRT and not far from where John Muir himself traveled during his first visit to Yosemite. For nearly 150 years, people have been coming here to admire this place–longer if you consider the Native American tribes that once migrated to and from this oasis along the Merced River. So after a dinner of Indian curry, as we perch on our bear canisters and count the stars, I ask Pete if he ever feels the Valley’s many visitors are loving it to death.

“Oh, some people think there should be a daily quota on the number of visitors allowed in the Valley,” he says. And yes, those crowds have an impact. But Pete says the bigger threat to the landscape is generated far beyond its granite domes. “Climate change has the potential to impact the park more negatively than the cars or hikers,” he explains, adding that 25 percent of the park’s pollution comes from China and its appetite for coal. He sees the effects of that carbon output every time he visits Lyell and Maclure Glaciers, where he’s been measuring the ice’s retreat since 1999. Compared to 100 years ago, their surface area has shrunk by 60 to 65 percent. “The factors causing the biggest changes here may be the hardest for us to control,” he reflects.

The next day, we leave the OBOFRT and pick up the North Rim trail, following it east toward El Capitan and Yosemite Falls. We cross open expanses of glacier-crushed granite where the blue sky blazes overhead, then enter a forest of giant sugar pines.

In a few hours, we arrive at the top of Yosemite Falls, the tallest verified fall in North America at 2,390 feet. Now, in mid-October, Yosemite Creek is a string of placid pools, and it’s difficult to imagine it as a mammoth firehose capable of blasting me off the cliff. Yet even without the crushing torrents of water I’d see during peak runoff in May and June, I still shiver when I lean out over the precipice and gape at the falls. From below, when runoff is low, the water can break up into wispy curtains and blow across the granite face in a rainbow of colors.

At the top of the falls, I bid farewell to Pete: This is where he must peel off, hiking back to his car via the Yosemite Falls Trail so he can spend tomorrow in the office. Tonight I’ll camp alone, a little upstream from the falls. “But tomorrow night,” Pete says, “you’re in for a treat. I wish I could stay out with you,” he sighs before turning for home.

The next morning, I pack quickly and follow the cairns up Yosemite Point, a smooth lump of granite that looms high enough above the falls to catch the morning’s first rays. I bask for a minute to warm my chilly fingers, then continue east along an open ridge affording 360-degree views: On my right is the Valley, 3,000 feet below; to my left, the rounded mountains of the Sierra present a montage of gumdrop-shaped hills of granite. I don’t meet another hiker for 4.5 miles, until I come to North Dome, a 7,542-foot promontory and a popular nine-mile dayhike from Tioga Road. A scant six people bask on the rock–a tiny fraction of the numbers you’d encounter on other, shorter dayhikes. Continuing on, I travel another six miles through sun-soaked forest so dry my boots stamp puffs of dust from the trail. The afternoon’s heat releases the pines’ pleasant fragrance, but by the time I reach Snow Creek and the gravelly bench where I’ll camp, salt and grit plaster my skin, so I strip for a bracing bath that’s almost as invigorating as the scene from my tent.

Tomorrow, I’ll descend into Yosemite Valley with its gridlocked parking lots and milling crowds. But tonight, blissfully removed from the traffic, I camp at Snow Creek, a grandstand spot with the best view ever framed by nylon.

Like the moon enlarged 1,000 times, Half Dome fills the sky above me, its circular sweep interrupted by impossible flatness. Its neighbor, Clouds Rest, contrasts Half Dome’s massive plane with random bulges and ripples that look like liquid, not stone. I’d expect to be over granite by now, after admiring it all week, but I’m more mesmerized than ever. As the slanting sun turns those monoliths orange, then pink, then an ominous gray, I can’t tear my gaze away. Maybe because there’s no one else here to bear witness, I watch with the eyes of 10 people.

Despite working and hiking alone, Colorado-based freelancer Kelly Bastone insists she likes people.

The North Rim: A Valley Tour de Force

Savor Yosemite’s icons in solitude on this 4-day exploration.

Hike it This 31-mile shuttle hike pieces together several trails and spurs for the best views and remote campsites in and above Yosemite Valley. From Rockslides trailhead (1), follow the now-defunct roadbed of Old Big Oak Flat Road Trail (OBOFRT). In the first few minutes, you’ll see the shaved granite wall of El Capitan piercing the skyline. At mile 1.7, where a massive rockslide blocks the road, follow cairns uphill (2) to the next intact section of roadbed. The upcoming 2.5 miles pass through dense manzanita; peek out at Bridalveil Fall, and end at a campsite near Cascade Creek (3). Top off water bottles and backtrack .6 mile the next morning to the North Rim trail (4). Turn left and climb through sugar pines, contour around El Cap Gully, and take the .3-mile spur trail to the 7,569-foot granite prow of El Capitan (5). Backtrack and head northeast for 1.8 miles to another spur up 7,779-foot Eagle Peak (6). Swing north, then east to Yosemite Falls Trail (7). Turn right and hike south to end this big 12-mile day at your second campsite (8). Catch the sunset glow at a nearby overlook of Yosemite Falls (9), a high-decibel whitewater ribbon falling almost 2,400 feet. On day three, see the sunrise from Yosemite Point (6,936 feet), then continue east for four miles to North Dome (10) for a front-row view of the cleaved granite face of Half Dome (see page 15 for photography tips). Hike north for 3.5 miles, passing a side trail to Indian Rock (11), a rare granite arch. In 3.8 miles, turn right onto Snow Creek Trail (12) and camp on a gravel bench (13) with oh-my-God views of Half Dome. The last day, descend 100-plus switchbacks over 2,500 feet into Tenaya Canyon (14). Follow the north side of Tenaya Creek, pass Mirror Lake, and pick up the free park shuttle (15) back to your car.

The Way To reach the unsigned Rockslides trailhead from Yosemite Village, take the Valley Loop road west to milepost 9 and park on the right, by the metal gate.

When to go Early summer for big, fat waterfalls (ask at the Wilderness Permit Station about creek crossings) or fall for thinner crowds and pockets of amber-colored leaves.

Go Guided Join Pete Devine and the Yosemite Association on a four-day, naturalist-led North Rim trip June 17-21, 2009. $340 per person ($289 for YA members); yosemite.org/seminars/index.html

Guidebooks and MapYosemite National Park: A Complete Hikers Guide, by Jeffrey P. Schaffer ($20; yosemitestore.com); National Geographic Yosemite National Park map ($12; natgeomaps.com)

Permits Required backcountry permits are issued based on your originating trailhead, and a quota system limits the number of permits issued each day. Sixty percent of each trailhead’s daily permits can be reserved up to 24 weeks in advance and cost $5, plus $5 per hiker. Download the application at nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wildpermits.htm, then fax to (209) 372-0739. Walk-in permits are free and available the day of or the day before your hike at any of the five Wilderness Permit Stations. Park entrance fee: $20 per vehicle.

Vacation Planner For travel beta inside and around the park, including hotel links and driving maps, visit myyosemitepark.com.