ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT

'(Photo by Brian Mockenhaupt)'

(Photo by Brian Mockenhaupt)

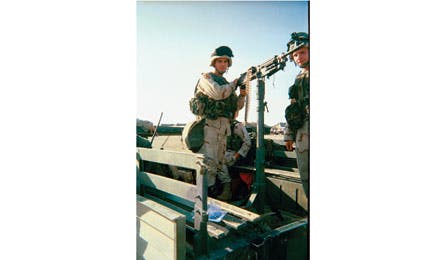

Rivera in Iraq in 2003 (John Rivera)

After the PCT. (Brian Mockenhaupt)

(Photo by John Rivera)

Approaching Mt. Rainier. (John Rivera)

Rivera washes off trail dust. (John Rivera)

A shelter atop Mt. Whitney. (John Rivera)

Breakfast on Fire Creek Pass. (John Rivera)

Getting the last resupply box. (Brian Mockenhaupt)

2,000-mile marker in Oregon. (John Rivera)

I had walked 25 miles in a single day once before, years earlier, and I was with John Rivera on that day, too, back between our first and second deployments to Iraq. We started in the morning,with rain clouds gathering.We carried M4 assault rifles and wore camouflage fatigues and black leather boots, helmets, and Kevlar vests with thick plates on the front and back that can stop high-power rifle rounds.Together, with more than 100 other soldiers, we snaked down the roads of the vast wooded training area in upstate New York’s Fort Drum, home of the Army’s 10th Mountain Division.

Several times throughout the day, other soldiers playing the enemy shot at us from the woodline with blank rounds, simulating an ambush. With our 40 pounds of gear, we’d dive for cover, return fire, and maneuver on the enemy, then continue our walk down the road. The rain started in the afternoon, and by nightfall we were soaked through and shivering and still a couple of miles from home. I trudged through the darkness on sore feet and wondered if the march would ever end.

That long, wet trek was easy—and flat—compared to my first day on the Pacific Crest Trail with Rivera. Over the day’s 26 miles through Washington’s Cascades, we climbed more than 5,500 feet, broken up by steep descents. Rivera, a 29-year-old former Army sergeant from Palm Springs, California, had already been on the trail more than five months, and he moved with an easy, steady rhythm. My technique more resembled an interval workout: several minutes of hard effort, then a long pause to catch my breath.

With water, food, sleeping bag, tent, clothes, stove, and too many odds and ends, my pack neared 40 pounds. Rivera, who carried about 10 fewer pounds than I did, had spent months working out weight-saving strategies—like hiking dry in areas of plentiful water. Better to guzzle a bottle and walk to the next stream carrying just some emergency water, he reasoned. At about 2 pounds per liter, no sense carrying the extra weight.

I thought about this on the day’s first climb: 1,200 feet up steep switchbacks, with more than 20 miles to go before camp (and another 170 miles in the following days as we hiked toward the trail’s end at the Canadian border). What extras were weighing me down?

Which reminded me of an email Rivera had sent me weeks earlier, during a brief resupply stop along the trail.

“One must divest one’s pack of all but the essentials,” he wrote. “And, in a similar way I feel like whatever a soldier might bring home from a war eventually must be discarded along these 2,663 miles of trail.”

It seemed Rivera had stumbled upon something important—a novel means to reconcile who he was before the war and who he is now, an attempt to dive into himself and resurface with a better understanding of where he had been, and where he is headed. But why does thru-hiking appear so effective? I came to the Washington wilderness to see what Rivera had learned over these months on the trail, and what this sort of deep, prolonged immersion in nature, coupled with a monumental physical task, had given him and might give other veterans. Myself included.

Another Army friend, Lloyd Hensrude, picked me up at the Seattle airport the day before my trek. We drove out to Stevens Pass in Wenatchee National Forest, 60 miles northeast of Seattle, to link up with Rivera. I hadn’t seen either of them since leaving the Army in 2005, after our second deployment.

Hensrude, 28, looked much the same as I remembered him—lanky, with a loping walk and easy smile. But I barely recognized Rivera when we met him. He hadn’t shaved since starting the trail near Campo, California, on the Mexican border, and now sported a long beard and shoulder-length black hair. His pants and shirt were worn thin from daily use. On his feet, a pair of desert- tan Lowa boots, the same type issued to soldiers in Afghanistan. This was his third pair.

The three of us hiked a couple of miles and made camp. Rivera built a fire and we drank a few Pabst Blue Ribbons and caught up on each other’s lives.

Like many veterans, we missed the camaraderie of the military, and were glad to reconnect out here in the woods. Part of this, of course, is the shared experience of serving in a combat zone. But there’s more: The world seems different after those experiences, or maybe you seem different, and those who best understand that are often far away. Learning how to cope with this feeling of isolation is just one of the challenges we all faced.

“It’s not a matter of just keeping busy. You have to find something that gives your life meaning,” Rivera said. “Trying to fit in, trying to find meaning, trying to put your life back together or start a new one—it’s tricky.”

Some make the transition from the battlefield just fine, or with a few bumps. Some don’t. We knew that. We knew Dacus.

Nine months earlier, on November 29, 2011, Sean Dacus, 31, who was in our infantry company, walked into a Grand Forks, North Dakota, emergency room and asked to borrow a marker. He sat on a bench outside, wrote “do not resuscitate,” his blood type, and “donate organs please” on his arm—then shot himself in the chest.

In the years after Dacus’s Iraq tours, his life had fallen apart. He’d been exposed to the same war as the rest of us: a few roadside bombs, occasional mortar and rocket attacks, and some sad and gruesome scenes that linger in the mind. And always the endless tension of waiting. Waiting for a trashpile to explode. Waiting for bullets to snap overhead. Waiting for home.

“When he came back, he was not the same person who went over there,” an uncle told a local newspaper reporter after the suicide.

Over these many years of war, the news has spiked with incidents like this and other heart-wrenching tales. Much attention has focused on veterans disfigured by bullets and bombs, or so mentally damaged that they’re unable to hold regular employment or maintain healthy relationships with friends and family. And some would argue that the shocking number of suicides—last year, 349 active-duty service members killed themselves (more than died in combat) along with hundreds of veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan— has not received enough attention.

But there is a vast swath of combat veterans that isn’t often talked about: those who may not bear the outward scars, and who may have decent support networks and coping skills, but who nevertheless struggle to find their place after they come home and quietly try to fit back into their old lives.

So it was for Hensrude, Rivera, and me: The war didn’t take our legs or our eyesight—or our will to live—but the war very much left its mark on us. After leaving the Army, I spent years writing about the military, traveling several times to Iraq and Afghanistan, in part because I felt more comfortable being around those in uniform than those who didn’t have firsthand experiences of the war. I didn’t need a psychiatrist to tell me that wasn’t the healthiest way of reintegrating, and I was intrigued when I heard about Rivera’s journey. Could hiking a trail fill in missing pieces?

“You’re supposed to get out of the Army and the world’s your oyster,” Rivera told me. “But all you’re doing is applying for jobs you can’t get, or getting jobs you don’t want. Maybe you have a girlfriend who doesn’t want to be with you anymore. Your self-confidence is eroding every day, and you’re surrounded by people who don’t understand where you’re at. You have no control over whether your family will understand you or not,”he said, “or whether an employer will hire you or not.”

But the trail, he said, can provide a sense of purpose. “You’re in control of everything on the trail. The route, mileage, food, shelter. Whether you hike alone or with others.”

In the morning, Hensrude walked back to his car, and Rivera and I headed north, higher into the Cascades, with stunning views of sparkling glaciers, rocky ridges, and alpine meadows. But toward day’s end I didn’t notice much of that, and the hike felt just like a road march: feet burning, shoulders aching, and head bent, watching the feet of the man to my front.

“The soldier’s mind-set is perfect for this trail,” Rivera said. “You get beat up every day and you take it.”

We camped that night next to an alpine lake, and after dinner Rivera squatted at the water’s edge, refilled his bottles, and stared at the mountainside that rose up from the lake.

“Only six days left on the trail,” he said.

“Are you excited?” I asked.

He waited a moment before responding. Snowmelt trickled over rocks across the lake.

“I’m a little sad,” he said. “This has been my life for the last half a year.”

Rivera started at Drexel University in Philadelphia in 2001 on an Air Force officer training scholarship. Riding the train in his cadet uniform in the weeks after the September 11 attacks, passengers constantly thanked him for serving. But I haven’t done anything yet, he thought. If this was to be his generation’s war, he didn’t want to spend it sitting in a classroom, so he quit school, joined the Army, and trained as an infantryman.

I wasn’t thinking about service and duty when I joined; I was drawn by the physical and mental challenges of military training and a long-standing curiosity about an American subculture about which I knew little. But our different paths brought us to the same place. Rivera and I arrived at Fort Drum at the end of 2002, and prepared for war. By early April, we were patrolling the streets of Mosul in northern Iraq, where we steeled ourselves for attacks that never came. Troops pushing up from the south had the hard fight, the real war. We were shot at just a few times, and roadside bombs hadn’t yet become the insurgent weapon du jour.

We were deployed to Iraq again in 2004, for another year, and that was more like the war we’d seen on the news, with bombings and shootings and the very real possibility of death. Rivera spent several months of that deployment as a guard at the interrogation facility where suspected insurgents were questioned before they were released or sent to Abu Ghraib prison. He watched over men accused of killing his comrades and became familiar with the thunderous crack and concussive punch of rockets landing nearby.

After leaving the Army in 2005, Rivera returned home to southern California and joined a Riverside National Guard unit, which was deployed to Iraq for a year in 2008. This time he was doing convoy security, protecting the trucks that shuttled vital supplies between the sprawling bases and small outposts. Though major combat had ended in the cities, Iraq was still dangerous, particularly the roads, where insurgents often planted improvised explosive devices. Rivera earned three commendation medals during the deployment, one for each of the roadside bombs he spotted before they could explode. Several bombs did hit his truck and others, and his company suffered a few injuries.

But it was the monotony and boredom, not the danger, that took a toll. “We had nothing to do,” Rivera told me. “We were only on missions half the week, and on those missions, more often than not, nothing happened. You sit in the truck for 12 hours, on the radio, repeating the same commands over and over, calling the same people and giving them the same information you gave them last time.”

Along with the oppressive tedium, Rivera felt a growing sense of futility. On one mission, after transporting pallets of bottled water to another base, Rivera spray-painted an X on a few pallets, on a hunch that some of the missions were just busy work. Several days later, while escorting trucks from that base back to the first, he found the pallets and water bottles with his mark. In that moment, he said, he felt like a character in Catch-22, Joseph Heller’s satirical novel about the absurdities and contradictions in war.

During those endless miles crisscrossing Iraq, Rivera hatched a plan for the thru-hike. He first heard about the trail in 2006 while working at the Mataguay Boy Scout Ranch outside San Diego, where he was the shooting sports director. He met two other counselors who had thru-hiked the PCT, which ran through areas he backpacked as a Boy Scout. They sent him a card with the PCT map while he was in Iraq, and this planted the seed. Planning the hike gave him purpose and something to look forward to once he returned home, but Rivera didn’t yet understand that the trail would help him in ways far more important than staving off boredom in Iraq.

“I used to be such a happy-go-lucky person,” he said. But after the last deployment, “I was bitter, and easily annoyed. I would get short-tempered over stuff. I’d get pissed if people didn’t pay attention to the fact that there were wars going on.” And he felt disconnected and behind. While he was away at war, his friends were starting their careers or finishing graduate school. He worried that he’d lost prime years of his life.

He started the PCT in the spring of 2010 and hiked the length of California, through the desert and the High Sierra, and into Oregon. He learned he’d been accepted to the University of California at Santa Barbara and couldn’t finish the trail before the school year started, so he abandoned the path after 1,726 miles. But he already knew he would return, after completing his political science degree, to hike the whole PCT, beginning to end. He’d discovered that a thru-hike offered much more than he’d imagined while pondering that PCT map in Iraq.

Walking a marathon every day through the mountains with a backpack takes a long time. Rivera typically hiked 2.5 miles an hour. With a few breaks, he was on the trail at least 12 to 14 hours a day. Even if he had a couple-hour conversation with another thru-hiker, that left many hours of solitude. Sooner or later, he said, he would run out of things to think about. After remembering movies and favorite foods, taking in the scenery, or planning future trips, his mind would feel empty, save for the boxes he’d tucked into the back corners, and they would demand attention.

“If something’s bothering you out here, you have to deal with it,” he said. “At home, you might have something on your mind when you’re at work, out with friends, or washing the dishes, but out here it’s different when your mind is facing a void.”

Had he been hiking with a group or on a shorter trip, he might never have reached this point of deep, stripped-down introspection. But alone on the trail, he’d find the same thoughts popping into his mind over and over, gnawing and relentless, the same hurts or frustrations. Tamped down for a while, they’d soon resurface. “Maybe it’s a conversation you had, something you’ve lost, or things you regret, things that have been unresolved,” he said. “You’re thinking This is stupid or It’s my fault. At some point, you realize you’ve been mad about it so often that it’s making you grumpy and sad. You have to leave it alone and drop it,” he said. “You can’t carry it forever.”

Since his first PCT hike in 2010, Rivera says, he hasn’t stayed mad about anything for more than five or 10 minutes, and he’s more accepting of himself. He let go of the frustrations that dogged him during the last deployment, that sense of futility. He couldn’t change the war; he could only make peace with his small role. He focused more on positive experiences from the deployment—close bonds he developed and his mentoring of several sub-par performers who became good soldiers.

“It’s about being okay with everything,” he said, “with who I am and where I am.”

Indeed, it was that quest that pushed America’s first thru-hiker. World War II veteran Earl Shaffer hiked the entire Appalachian Trail in 1948 to “walk off the war” and flush from his mind the sights, sounds, and sharp memories of loss. In recent decades, science has backed up the psychological benefits Shaffer sought, with research that shows wilderness solitude and extended hiking can reduce stress, improve understanding of purpose, and increase both mental well-being and connectedness with the world.

And for veterans, the wilderness may offer additional unique benefits. “Exposure to war and trauma can disrupt the most basic beliefs about safety, trust, and control,” says Jennifer Romesser, a clinical psychologist with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Salt Lake City who is studying the effects of taking veterans on outdoor activities. “Nature can help reconnect veterans with the experience of positive emotion, and develop a renewed sense of awe and appreciation for the outdoors.”

Shaffer wasn’t the only vet heading to the woods after World War II. Veterans from the 10th Mountain Division—the unit with which Rivera and I served—played key roles in developing outdoor recreation in America, using their training in skiing, mountaineering, and backwoods survival. Paul Petzoldt founded the National Outdoor Leadership School, David Brower led the Sierra Club, and other veterans established ski resorts across the northeast and the Rockies.

Nature no doubt brought them healing, but taking war veterans into the outdoors specifically as therapy didn’t arise until after the Vietnam War. And the idea has gained significant momentum in recent years. As part of the explosion in veteran services over the past decade, scores of programs have sprung up to take vets surfing and fly-fishing, paddle boarding and climbing. Many of these are short, weekend-type courses, with some stretching to a week or longer. The programs can give participants new toolkits for life challenges—and confidence from overcoming physical obstacles and learning new skills—but they don’t offer the deep solitary introspection Rivera experienced on the PCT. Neither are they long enough to be habit-forming—the difference between a yoga retreat and months of regular practice.

Like thru-hikers, soldiers are not made over a weekend. Unlearning old ways and forging new habits—of the mind and body—require weeks of repetition, reinforcement, and the steady, repeated confrontation with obstacles. Months on the trail offer this opportunity for change.

Hiking the PCT made Rivera an evangelist for thru-hiking and deep immersion in nature, and he believes other combat vets could realize the same growth he has. But he knows there are many who need a different type of help. For them he’s raising money—through public speaking before the hike, and soliciting donations along the trail—for the Wounded Warrior Project, which helps injured service members and their families with everything from job placement and physical rehabilitation to combat-stress programs that take veterans rafting, rock climbing, skeet shooting, and skiing. Before the 2010 hike, Rivera started a blog called Help Feed Starving John, with a list of food-drop dates and locations, along with sample menus. Friends and family covered more than half the food drops. If people were willing to buy him food, they’d likely donate money for a charity, he figured.

For his 2012 thru-hike, Rivera teamed up with a high-school friend and Marine, Tyler Blauvelt—Task Force PCT they called themselves. They walked together through much of California, but parted when Blauvelt slowed down to hike several days with his brother, who wasn’t accustomed to the high mileage. When I met up with Rivera, Blauvelt was still a week back.

But that’s the nature of the trail, everyone moving at his own pace and hiking for his own reasons, an endeavor both individual and communal. Take your time on the PCT and it might stretch to six months or more, but even a faster hiker needs about four months of sunrise-to-sundown walking.

“There’s no way to rush anything out here,” Rivera told me. “You can only go so fast. You’ve got to have patience to do this, and if you don’t, you are going to acquire it soon enough.

“Even when the trail seems determined to thwart you, you just have to accept it,” he says. “You can yell all you want, but there’s no one to argue with. Everything just is what it is. And if you finish the trail, you’ve put your mind through half a year of training at just accepting things as they are.”

He told me about one particularly frustrating week, leaving Cascade Locks in Oregon. With the next resupply a week away and a long, dry stretch in the immediate miles ahead, the extra food and water swelled his pack to 45 pounds. He hadn’t carried that much weight in six weeks and he was burned out from 30-mile days through Oregon. A heat wave pushed temperatures into the high 90s and the first miles presented a steep climb. “But the benefit of having done this long enough is that when I find myself cursing, I realize that’s just slowing me down,” he said. “I’m just losing my breath. So okay. Calm down. Just get it done.”

The trail soon gave me just such a lesson in patience and perspective.

In 2003, flooding knocked out the 265-foot Skyline Bridge over the Suiattle River. The Forest Service built a new bridge downriver, but that detour would add more than 5 miles. Instead, we could cross the river on one of the precarious-looking fallen trees and walk several miles of the now-disused section of the PCT.

When Rivera first told me about the reroute, on my first day on the trail with him, the extra miles didn’t seem so bad, and more prudent than a sketchy log crossing over a frothy, fast-moving river.

But by the third day, 75 miles in, I’d learned some simple trail math: Five miles is two hours, and two extra hours on the trail can be a very long time, when blisters rub raw and neck muscles seize, or my right big toe throbs so badly I’m sure it would be less painful to just cut it off.

We opted for fewer miles. We scouted a few crossing possibilities from the trail, then bushwhacked and slipped 50 feet down a steep embankment to Vista Creek, where two trees had fallen nearly side-by-side, creating a safe-looking bridge, which we crossed. After 200 more feet of bushwhacking, we found the trail and started down it, rather pleased with ourselves for having saved two hours.

But after the first mile, doubt crept in. This seemed to be the old PCT, but the map showed us gaining 1,500 feet, while we’d only climbed a couple hundred. Had we instead gotten onto one of the smaller local trails? Still second-guessing ourselves, we pushed on and soon heard whitewater.

The trail ended at the edge of a 200-yard-wide stretch of rock and sand. Here we saw the full destructive force of the 2003 flooding, with 100-foot trees pitched like cordwood and the embankment scoured away, leaving 100-foot drop-offs in places. We spotted the first of a half-dozen stone cairns marking a zigzag path across the sand and rocks. This must be the way. On the far side, the Suiattle River raged. We crossed on a fat log, stepping over strips of loose bark, and I pushed from my mind an image of falling 8 feet down to the water and being sucked under, weighted by my pack, bouncing off boulders.

We climbed into the forest and our optimism waned. For a half hour, we crawled over an endless tangle of fallen trees looking for the trail. If we went much farther, we could easily get lost. With the sun dipping behind the ridge, we finally turned back, recrossed the Suiattle, and backtracked 3 miles.

We made camp in the darkness, right where we’d started, next to Vista Creek. In trying to save 5 miles, we’d added an additional 6.

In the morning, we took the detour to the sturdy new bridge. Another hour later, we stepped into a clearing and there it was, a few hundred feet away, the tree we’d crossed—twice—over the Suiattle River. If we’d gone another 100 feet through the forest, we would have found the trail.

We saw the tree and laughed. As Rivera had told me, you can get mad, but the trail just is what it is. Besides, we experienced a little adventure, we didn’t get lost in the woods, and neither of us was swept downriver. I could have used that perspective while dealing with frustrations during my deployments. I played a tiny part in the war, with limited influence, and often the best I could do was to try to keep myself and the people near me safe. But, as it was for Rivera, that realization was slow in coming, only drawing into full focus after I left the battlefield. Which made me think how helpful this hike would have been soon after I left the Army and set about finding my place back in the civilian world. The trail isn’t a cure-all by any means, but it’s an amazing source of perspective and a refuge from a world that, for some veterans, can feel even more confusing than the war zone. By this point in the trip, I’d had enough time alone in my head for a first glimpse of the mental housecleaning Rivera described. Even if he and I spent two hours in constant conversation, that left another eight or nine hours of quiet hiking. Without life’s normal distractions, thoughts doubled back on themselves, refusing to be pushed aside, demanding attention. This may not be the most efficient way to work through an issue, but it’s effective. Some family stresses that had nagged at me before the trip started to seem far more manageable. After only a few days on the trail I knew I would be back. Even if I never made time for a full thru-hike, I would return for regular retreats and the sort of mental tune-up I hadn’t found anywhere else.

And as for my immediate circumstances, yes, the blister on my right heel burned, my back ached, and my right big toe throbbed. But what could I do? Put on some moleskin and just keep walking.

We hammered out 28 miles, made camp next to the rumble of a rushing stream, and built a quick fire that seemed wonderfully luxurious and decadent after such a long day. The next morning, we hiked a quick 5 miles into North Cascades National Park, where a bus took us and a half-dozen other thru-hikers into Stehekin, the last resupply point on the PCT.

We returned to the trail by mid-afternoon and put in 8 miles before nightfall, the last 2 under a sky that threatened heavy rain but gave us only a cold, light drizzle. We watched a patch of trees high on a mountainside burn like giant candles in the twilight—a small forest fire from a recent lightning strike.

On Rivera’s last day on the trail, we woke to an icy wind whipping through our campsite in a high pass, 26 miles from Canada. As a welcome morning sun crested a ridgeline, we hiked north, up and down, at times chatting, at times a quarter-mile apart. Ahead of us, the skinny, tan ribbon of trail snaked along the mountainsides. Through the afternoon, we walked together, but mostly in silence, on a long, 3,000-foot descent, from a mountaintop at 7,100 feet to Castle Creek on the Canadian border.

With just a few miles to go, I asked Rivera what he was thinking about. “To-do lists,” he said. Graduate school applications. Half marathons he would run in the coming months, training for a full marathon. Jobs. Thank-you cards for all the donations. Test dates for the State Department’s Foreign Service Exam. That’s his dream job, working as a foreign-service officer, and what a sight he must have been to dayhikers as he read The Economist and Foreign Affairs while walking the long, flat stretches through Oregon.

In another day, he would no longer be Oddball. Every thru-hiker has a trail name, which is given, not picked, often arising from a funny moment. Along the way I met Salty Snacks and Dump Truck, Spider and Pilfer. Rivera’s name was Oddball, for Donald Sutherland’s character in the World War II movie “Kelly’s Heroes,” whose lines he’d been quoting. Another hiker picked up on the reference and assigned the name. Tomorrow he’d be heading back to a world where everyone knew him as John. But, for now, he walked on, out of the mountains and deep into the forest. And then, in a small clearing, he was done.

Rivera removed the top of the border marker, a 4-foot-tall brass obelisk, and pulled out the trail log, where hikers can leave last thoughts. He stuck a black-and-white Wounded Warrior Project sticker in the book, wrote a few words about finishing the trail after the aborted 2010 try, then signed off: “Oddball, U.S. Army Infantry, ’02-’09.”

In the pale, fading light of early evening, he climbed to the highest post of the wooden, four-tiered PCT monument, balanced on the small perch, and stretched his arms to the sky.

Help a Hero Hike A new program encourages veterans to follow in John Rivera’s footsteps.

Rivera was in the vanguard of what could be a wave of veterans thru-hiking America’s long trails—and reaping the benefits. This year, Warrior Hike launches its Walk Off the War program with 13 wounded vets who will attempt to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail. Veterans Sean Gobin and Mark Silvers conceived the project—and enlisted partners like the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and Veterans of Foreign Wars—after their 2012 thru-hike on the AT. Participants get gear, food, transportation, and lodging support through program sponsors. Up next: In 2014, Walk Off the War will expand to the Pacific Crest and Continental Divide Trails as well. To apply for a spot, donate, or follow hikers, go to warriorhike.com.

No time for a thru-hike? Veterans Expeditions (vetexpeditions.com) connects vets with all types of outdoor activities.