Higher Calling: Adventure in Valencia, Spain

'Guide Jose Miguel Garcia in the Aitana Mtns.'

Photos by Michael Lanza

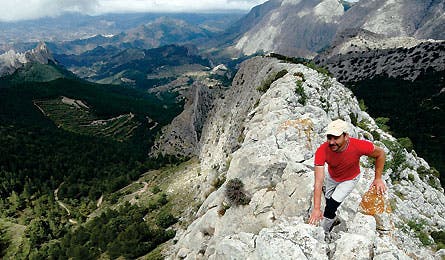

Guide Jose Miguel Garcia in the Aitana Mtns.

A climber on Ponoch Via Ferrata.

Jan Novotny tiptoes Bernia Ridge.

A hiker ascends a ridge above Guadalest Valley.

Biking towards Clifftop Castle ruins.

I’m standing on a rocky ridgetop amid the crumbling ruins of a castle built by Moors during their seven-century rule over most of Spain. It seems like a safe spot to dig in: Beyond these broken walls, the ground plunges hundreds of feet over cliffs and mostly treeless, 50-degree slopes. Today, though, there’ll be no rain of arrows from attacking marauders–only me and my guide, José Miguel Garcia, hiking through a sea of craggy limestone mountains. Below us, bleached terracotta villages dot the landscape, ensuring that a post-hike feast of paella, tapas, and wine is never hard to find.

It’s the second morning of my five-day trek across a chronically sunny range of mountains so obscure they lack a unifying name. Forming a compact cluster about 30 miles long by 10 miles wide (similar to Wyoming’s Tetons, minus the snow and ice) in the central part of Spain’s east coast, they’re known only informally as the Aitana Mountains, for the area’s highest summit. After the Christian Reconquista drove out the Moors in the late 15th century, this area’s population shrank by two-thirds, and even now, few people travel the highland footpaths.

Located in Spain’s Valencia region, the soaring cliffs and razored ridges of the Aitanas loom within sight of tourist-flooded Mediterranean beaches; from every high point, the shimmering sea fills the southern horizon. But because the peaks reach just 5,000 feet–mere nubbins compared to the Alps and Pyrenees–they remain largely unknown. In fact, their adventure potential has been mined only in recent years by a trickle of hikers and climbers who’ve discovered multisport gold–in the form of mountain biking, climbing, and trekking.

My goal is to sample it all. Over the coming week, I’ll tackle a 60-mile village-to-village trek, then mountain bike to a hidden castle. I’ll scale an iron ladder bolted onto an 800-foot cliff, and scramble along a wildly exposed knife-edge ridge that Euro climbers compare to the headiest traverses in Scotland’s revered Highlands. And in good Old World style, I’ll feast every evening on Spanish delicacies like stuffed aubergines, paella, and olleta de blat (a stew containing various pig parts from ribs to hooves). I’ll wash it all down with enough vino to float a Spanish galleon.

It’ll be a spectacular decathlon of recreational, cultural, and epicurean excess. The only question is what will cause me to drop first: complete physical exhaustion or severe caloric overload.

“See that crack in the cliff?” says José, pointing to a barely discernible slot 400 feet above us. “That’s the pass.” On the third day of my quest, José and I are hiking up the area’s highest peak, 5,128-foot Sierra de Aitana. So far, we’ve climbed Sierra d’Aixorta, marched for several hours over Sierra de Serrella, and eaten half our weight in paella. Now we’re hoping to traverse Aitana’s long alpine ridge. But to get there we have to access the cleft–and from here, that looks close to impossible.

Once we’re climbing, though, it’s easier than it looks. We scramble across boulders, airy ledges, and tilted slabs, then step through the shoulder-width mail slot, emerging onto a plateau carpeted with brilliant wildflowers: purple-flowered Cistus albi, wild thyme and rosemary, and the golden, sofa-like cushions José calls “nun’s pillows.” To every horizon stretch white, gold, and gray limestone buttresses rising high above valleys terraced with almond and olive orchards.

As we hike, José explains how 10 years ago he envisioned a multiday trek across the mountains between the villages of Castell de Castells, Guadalest, and Sella. And how he used interviews with old sheepherders, as well as GPS and Google Earth research, to link trails built centuries ago by farmers, traders, hunters, and nevaters, who harvested ice blocks from stone wells (still intact today). Steep, rocky, and largely forgotten, the paths often take the most direct lines over peaks with 3,000 feet of relief. Which explains, at least in part, why we walk for hours without seeing anyone.

The wild boar tracks grab my attention, but José assures me that the 300-pound feral porkers do their rampaging after dark. Then the cliffs come into view, and I forget about kegs of ham with dangerously pointy tusks. On the fourth morning of our trek, crossing the mountains between Guadalest and Sella, we’re approaching the Piña Roc–literally “rock rocky outcrop,” according to José. (Don’t laugh: The redundancy seems appropriate to the ocean of limestone spread out before me.)

With necks craned skyward, we walk below a series of vertical walls and amazingly thin fins, some 400 feet or taller. Their chalky faces spring from a lush carpet of low trees and bushes. José, a longtime climber, gets a beatific expression and looks for a moment like he might break out in song. Ten hours and eight technical miles later, at a restaurant in Sella, we tuck into fistfuls of Marcona almonds, wash them down with a local Merlot, then binge on a dinner of steak and potatoes in a Roquefort-and-pepper sauce served on a platter with the diameter of a California redwood.

Afterward, I’m too full to stand up and too buzzed to remember how many miles or vertical feet we’ve logged. But one thought burns through: This is one of the most gorgeous treks I’ve ever taken–and I still have several days of climbing and biking ahead of me.

“Up, up, up,” Toni Serrano Ortuño says, emphatically repeating one of the few English words he knows. The morning after ending my trek in Sella, I’m back in Guadalest mountain biking with Toni, owner of Cases Noves B&B. An avid rider with legs like poplars, Toni is training for a 50-mile race that climbs 7,000 feet. As a gesture of cross-cultural solidarity–or maybe just to put a hurt on the Yankee–he’s invited me on a ride onto the flanks of Sierra de Aitana.

We grind up steep gravel roads, rolling past medieval farmhouses, then turn onto singletrack and climb steadily higher. At a pass 2,000 feet above Guadalest, we leave the bikes and hike in our cleated shoes up a rocky footpath so steep we have to grab handholds. Our destination: the ruins of a castle perched atop the narrow crest of this ridge. Panting, we enter what remains of it–decaying walls and a turret overlooking Aitana’s miles-long ramparts, with the Guadalest Valley’s terraces of neatly pruned almond and olive trees falling away far below. I’ve done hard, beautiful rides all over the States–but never one that ended at a mountaintop fortress.

Our descent drops us through endless bends on narrow mountain roads. We fly back to Guadalest, where–as if there was no conceivable alternative–Toni and his wife Sofía take me to a small restaurant in the town’s obligatory castle. One of the perks of traveling in such an undiscovered area is that you’re treated more like visiting royalty than a faceless tourist. Eating with Toni and Sofía feels like an impromptu festival. They know everyone in the restaurant–staff and diners alike–and gesticulate wildly as they banter in rapid-fire Spanish. The kitchen produces a delicious chicken-and-garlic dish and Sofía keeps my wine glass full.

Kicking back in a creaky wooden chair, contemplating whether my health insurance will cover stomach pumping, my eyes glaze over when Sofía turns to me and declares more than asks, “You will have dessert, yes?”

The ladder of iron rungs appears to rise endlessly into the sky, but José insists it only climbs 800 feet up this cliff.

The morning after my bike ride, we’re standing at the base of a peak named Ponoch to climb a via ferrata–Italian for “iron road.” Like its counterparts in the Dolomites, where the first vie ferrate were built to help move troops through the mountains during World War I, this one has a steel cable bolted into the rock, paralleling the rungs. Wearing climbing harnesses, we clip into the cable with a tethered carabiner for safety.

Unlike with rock climbing, there’s no time spent figuring out moves and fussing with gear, so we move quickly, pausing only to snap photos of massive cliffs against a blue Mediterranean backdrop. I’ve climbed for almost 20 years, often on bigger walls than this–and without a ladder. Yet for the entire two hours we spend aloft, I feel climbing’s familiar tongue-swallowing exhilaration. This is no amusement-park thrill. Dead-vertical to overhanging in places, Ponoch’s via ferrata is extravagantly exposed. After topping out, we descend into a valley splashed with the bright greens of May. A snaking mountain road leaves only a faint fingerprint of civilization.

Bernia Ridge looks like it was ripped out of the Dolomites and planted on this hilltop above Spain’s coast. A jagged scrawl of razor-sharp limestone juts up to 400 feet high and stretches for nearly three miles. On my final day in Spain, José and I are joined by his climbing buddies, Laszlo, a Hungarian Frank Zappa lookalike, and Czechs David and Jan. We’ve come to make the technical traverse of Bernia, a full-day adventure that’s a rite of passage for locals.

A cave entrance at the ridge’s base reveals the most unlikely karst formation I’ve ever seen: A tunnel three feet in diameter bores about 100 feet straight through the ridge. Crab-walking, we inch toward a tiny circle of daylight at the far end, at times contorting our bodies to avoid dunking our hands into the shallow puddles littered with sheep dung.

We scramble onto the narrow ridge, then walk and crawl for the next four hours along its undulating, fractured spine. On the steepest sections, we rappel down short cliffs; at the crux, we belay each other across a 30-foot tightrope walk.The awesomely exposed fin is barely wider than my shoe.

Standing atop Bernia, with the Ponoch, Puig Campana, Sierra de Aitana, and other now-familiar peaks visible in the distance, I’m awed yet again. I’ve crammed a summer’s worth of world-class adventure into a week–and all of the scenery, incredibly, is unknown back home. And I’ve only scratched the surface. Before leaving, I’m already scheming a return visit to investigate the hundreds of rock-climbing and canyoning routes, not to mention an out-of-the-way restaurant where–according to José–they serve a really great paella. And likely some vintage Merlot.

Michael Lanza gained five pounds during his weeklong adventure in Valencia.

Trip Planner

Getting there

Numerous airlines fly to Valencia via Madrid, and Delta plans to begin direct flights from New York in June 2009. From Valencia, it’s less than two hours’ drive to Castell de Castells.

The trek

The author walked from Castell de Castells to Guadalest to Sella along a 60-mile route marked with white and yellow signs. Bring trekking poles for the steep trails and scree, and light pants or zip-offs for the thorny vegetation. See “Guidebook and Maps” below for details on this route and additional trekking options.

Multisport

The Bernia Ridge traverse is marked with red blazes and arrows; give it a full day. A 40-meter rope is required for the rappels (from bolt anchors) and about 50 feet of bolted 5.7 climbing. Learn more about Bernia Ridge, Ponoch via ferrata, and area canyoning at geocities.com/costablancaclimbing/otheractivities.html and ryanglass-mountaineering.co.uk/html/topos.html.

Season

You can hike here year-round (the region gets 300 sunny days annually), but fall and spring are best; avoid the heat of July and August. Hiker traffic is always low.

Lodging and Food

A room in a village hotel or B&B (like Cases Noves B&B in Guadalest, destinoguadalest.com) starts at $120/night for a double (depending on the exchange rate). Local restaurants include the Hotel Serrella in Castell de Castells; Restaurante la Montaña in Benimantell; and Bar Paco and Isa & Toni’s in Sella. Learn more about area lodging choices at muntanyadalacant.com. Backcountry camping is permitted, but the rocky terrain and thorny vegetation can make sites difficult to find.

Outfitter

Terra Ferma (José’s outfit), terraferma.net

Cost

DIY: $$$ // Guided: $$$$