The Quest: 1 Man, 439 Wilderness Areas

Gila National Forest (Photo: Teresa Kopec via Getty Images)

They say you only get one chance to make a first impression.

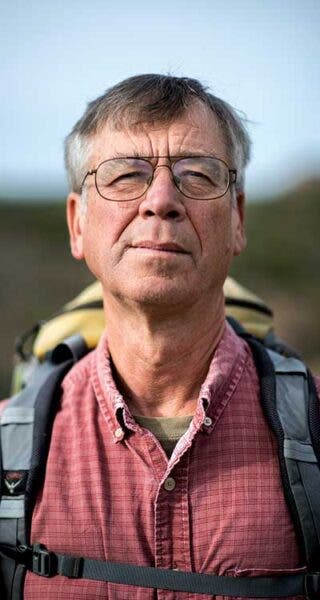

Fortunately, Steve Brumbach had two the night we met. I encountered him by chance at a dinner in Rock Springs, Wyoming. Bespectacled and deeply tanned, he was taciturn at first. But he left me with his business card, which reads: “Chemical and Nuclear Sciences (retired), Very Serious Hiker” and is printed with an atomic energy symbol and a pair of hiking boots. The card said something about the man that his demeanor didn’t, and who self-identifies as a Very Serious Hiker, anyway? I wanted to know what he meant.

I used that card to start a correspondence and convinced Brumbach to join me on a hike. He, his partner Maya Spies, and I planned a trip to New Mexico’s famed Gila Wilderness. It wouldn’t be his first visit. Brumbach has hiked an astonishing 430 of the 439 U.S. Forest Service wilderness areas. On the eve of the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, he must know the country’s wilderness system better—in a boots-on-the-ground way—than anyone else alive.

On the first day of a four-day, 36-mile loop, we hiked through pleasant ponderosa forests, stepping around dozens of helmet-size mounds of mustard yellow scat composed of the stomach-churned remnants of huckleberries and pine nut kernels. Nudging a mound with his boot, Brumbach speculated that the big fires along the Mogollon Rim last year, “perhaps combined with the heavy floods of the central canyons this fall, must have pushed around a lot of bears.”

Brumbach keeps track of geographical changes like these and deduces trends at every wilderness he visits. I asked him if he’d ever had problems with bears on his journeys. His reply: “Never.”

This surprised me, given Brumbach, a super-fit 70-year-old, has hiked in Alaskan wilderness areas where bears far outnumber backpackers.

Brumbach stopped on the trail a short distance farther along and cocked his head. “Flicker,” he said, identifying a faint bird call. “They like to make noise.” He paused contemplatively, head back, looking in the direction of the sound. But he was still thinking about bears. “The most dangerous animal in the wilds,” he said, “as in the rest of the world, walks on two legs.”

Brumbach speaks slowly, in complete, declarative sentences with emphatic annunciation, like a man accustomed to thinking before opening his mouth. Not surprising for a scientist. Brumbach got his Ph.D. in chemistry from Penn State, worked as a physicist for Argonne National Laboratories for 20 years, and later became a chemistry professor at Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs (hence the first part of his business card).

On our second day in the woods, while negotiating the upper reaches of Turkey Creek, I noted his steady, confident, long-striding gait and asked how long he’d been hiking. “That has two answers,” he said. “All my life, and since 1978. I have been exploring on foot my whole life, and was in the Boy Scouts in the 50s, but it wasn’t until a 12-day trip into the Wind River Range in 1978 that I got hooked. It was my first trip in genuinely Western terrain and the sheer beauty of the place astounded me. Thereafter, serious hiking became an important part of my life.”

Brumbach left a good job in Illinois and moved West. But it wasn’t until the spry age of 57 that he began his quest to hike all U.S. Forest Service wilderness areas (the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also manage wilderness areas, but the USFS claims the lion’s share of them by number of units, if not by area).

“I’d visited about 50 wilderness areas, and from my limited experience at the time, I decided the Forest Service wildernesses had the best to offer. The motivation to do them all was elementary: I wanted to experience the most scenic, most aesthetic natural places.”

It was no accident that Brumbach, Spies, and I had chosen to hike in the Gila. It’s the world’s first official wilderness area, designated on June 3, 1924, due largely to the intense commitment of a young man named Aldo Leopold. The Forest Service set aside more than 700,000 acres of the Gila River headwaters with the simplest of management instructions: “Prohibit roads and hotels, and then leave it alone.” (The administrative act establishing the Gila Wilderness foreshadowed the congressional act that followed four decades later.)

Back in 1909, Leopold, one of the nation’s first Yale graduates in the newly created field of forest management, was assigned to hunt bears, wolves, and mountain lions in the territories of New Mexico and Arizona. But on the ground, he quickly began to rethink the balance of predators and prey needed for a healthy, functioning ecosystem. Leopold was one of the first land managers to recognize that a sustainable ecosystem was an exceedingly complex web of intricate interactions among all species. Aldo Leopold is now famous as the father of the modern conservation movement, cofounder of The Wilderness Society, and author of the seminal, very personal biodiversity treatise A Sand County Almanac.

Leopold didn’t live long enough to see his dream of a national wilderness system realized. But 16 years after his death in 1948, following an eight-year struggle and 66 drafts, Congress passed the Wilderness Act, signed by President Lyndon Johnson on September 3, 1964. Today there are 758 wilderness areas in the National Wilderness Preservation System, comprising more than 109 million acres, all governed by this poetic definition:

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor and does not remain.

In 1964, one could imagine hiking in all of the wilderness areas. The new law established 54 designated units in 13 states. Fifty years later, hiking in even a quarter of them looks nearly impossible. But Brumbach set about his quest methodically, like any scientist would. On one road trip to the Eastern U.S., he hiked in 25 wilderness areas in 33 days. (To mark it off the list, his minimum visit is a hike of at least a few hours.)

“Most of them were dayhikes because the wildernesses are just so small in the East. And they all look so damn similar. I started to ask myself, ‘Didn’t I do this exact same trail yesterday?’”

That’s not to say he didn’t come to appreciate these smaller wilderness areas. “I was in West Virginia at the Spice Run Wilderness trailhead when a grizzled old guy roars up in a service pickup and jumps out. He was curious why someone from Wyoming—he saw my plates—would care about this remote, little piece of land.” The man took Brumbach to a small hunting camp and shared stories and photos of how generations of his family had explored and hunted in the hushed dales—a wild slice of oak and hickory and maples. The experience helped Brumbach appreciate the value of all wilderness—even if he remains biased toward the West.

“In my view,” expounded Brumbach, the third day in the Gila, “there’s nature on the grand scale—the Wrangell-St. Elias Wilderness in Alaska, for example—and nature at the detail level, like squirrel tracks and brilliant oak leaves in the Joyce-Kilmer Slickrock Wilderness along the border of Tennessee and North Carolina. I enjoy them both, but my heart is drawn to the majesty of the big Western wildernesses.”

Brumbach has spent more than 1,200 days hiking in wilderness areas—not including getting to and from his destinations. He acknowledges the wildernesses in Alaska, which invariably require a bush pilot flight, have been expensive. Last year alone he spent $9,000 on bush flights. “But everything in the Lower 48 is extremely cheap,” he says. He never stays in a hotel, just sleeps in his Nissan Frontier pickup bed at the trailhead or a nearby campground.

One afternoon in New Mexico, as the three of us were making a steep, ankle-turning ascent of Granite Peak, I asked him if he’d ever been hurt on his adventures.

“Never. I am a cautious person. I am not impulsive.”

We stopped to catch our breath.

“To tell you the truth,” he added, “I’ve never had a single negative experience on the trail.”

Pressed, he admitted that he once left his tent poorly staked in Indian Basin in the Wind River Range on a windy day, then climbed Jackson Peak. When he returned, his tent was floating in a lake. “The wind eventually blew it to the far shore. Surprisingly, my sleeping bag, which was inside, was still dry.”

All those wilderness areas and no snakebites or scorpion stings, no broken legs nor lost-for-days, no near-drownings during river crossings or nasty glissades during pass crossings. And most of them done solo to boot.

Brumbach doesn’t deem going alone the least bit dangerous.

“You simply need to know your limits, mental and physical, and not become so goal-oriented that you lose your rationality.”

I suppose you can’t take the scientist out of the hiker. Still, the hiker in Brumbach has his say on the final day. “In modern society, we’re used to living in material comfort and getting our way,” he said, “but in the wilderness, we have the chance to revert back to a simpler life and must accept the day on nature’s terms, not our own. There’s a valuable lesson in that. Wilderness returns us to rhythms that are ancient parts of ourselves that have been lost living in cities.”

Do anything long enough, with enough passion, and you will become a connoisseur of your subject. Keep doing it, keep thinking about it, and you become a critic.

Brumbach has ranked all 430 USFS wilderness areas he has visited according to a rating system, which he admits is subjective, hiker-biased, and sometimes based on limited experience. For example, he has spent more than 200 days in the Wind Rivers on some 40 trips, while only a few hours in sundry small Eastern wildernesses. Here are his criteria:

- Is it wild? Traffic noise, crowds, litter—signs of civilization—diminish wildness.

- Is it scenic? Face it, some landscapes are more appealing than others.

- Does it have unique biological or geological features (i.e. is it interesting)? Fjords, brown bears, spires of granite or cactus?

- Is it hikable? Swamps, thickets, briar patches are not hikable.

- Is it overrun with domesticated livestock? Livestock push out endemic species. Besides, sheep chew the grass to dirt, and cows shit everywhere, especially in sensitive riparian zones.

Although the Wilderness Act is now 50, there has yet to be a legal definition of “wilderness character.” In a paper in Park Science that investigates the issue, the authors identify five fundamental traits of wilderness that match Brumbach’s criteria remarkably well: naturalness (“free from the effects of modern civilization”); the opportunity for solitude; undeveloped (“wilderness retains its primeval character”); untrammeled (ecological systems are “unhindered by human control”); and contains “unique features” of some kind (such as geology, culture, or history).

But Brumbach goes even further—he has ranked each wilderness from one-star up to five-star. The one-, two-, and three-star rankings aren’t worth mentioning. In the four-star category are some classics—Frank Church in Idaho, Emigrant in California, Maroon Bells-Snowmass and Holy Cross in Colorado—but also some surprises, like the Garden of the Gods in Illinois.

There are only 22 places on his five-star list, which according to Brumbach means, “Go. Go out of your way to visit this area.” Click Here to see the complete list.

Curious, I asked Brumbach to name his top three wilderness areas.

“Bridger, Fitzpatrick, Popo Agie. Does that make me provincial?” he asked rhetorically. All three are in Wyoming, his home state. “I don’t think so. Remember, I am a hiker. I want to hike in the wilderness. Accessibility matters to me. I don’t have to book a bush pilot or a commercial plane to visit these wildernesses.”

On the final afternoon, we were walking along conversing about the visionary foresight of the Wilderness Act and the ecological ignorance that is now pervasive in the U.S. “The Act’s founders knew what was coming down the road, literally and figuratively, and knew they needed to do something about it,” Brumbach said. “The Wilderness Act could never pass through Congress today.”

Engrossed in conversation, I managed to lose the trail. We halted in an open forest, pulled out the topo, and checked the GPS. I suggested that we were still going the right direction and should just bash onward. Brumbach looked at me quizzically, obviously perplexed by such an ill-conceived notion, and quietly advised that we merely follow the GPS bearing back to our last waypoint. Which we did and quickly located the trail.

On our last night, around the campfire, satiated by a dinner of rice and beans, I asked Brumbach about the remaining Forest Service wilderness areas on his list.

He has nine more to hike. Five are in Alaska, and there’s one each in Pennsylvania, Michigan, California, and Puerto Rico. Brumbach departed for Alaska as this issue went to press, and should be well on his way to finishing his quest by the end of summer.

“I already have my bush flights booked,” he said with a wide grin.

I asked him if he thinks his quest is an obsession.

“Well, I guess that is the right word,” he replied, almost reluctantly. “In my defense, I can say that it has given me the magnificent opportunity to see nature up close and personal, undisturbed, in solitude.”

In Alaska, Brumbach plans to visit the Warren Island, Tracy Arm-Fords Terror, Chuck River, and Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands wilderness areas on one trip, and Endicott River Wilderness on a separate adventure, later in the summer, when stream crossings are safer.

“I’m told the Endicott, because of its extreme inaccessibility, might be the least-visited national forest wilderness.”

And then what? What does a man do who has hiked all 439 Forest Service wilderness areas? A man who is fitter and sharper than most men half his age, and who is committed to hiking through the most aesthetic landscapes in America?

Brumbach was sitting on a log, his face glowing in the firelight.

“There are 61 national park wilderness areas, and I’ve already hiked in 31 of them. Thirty to go!” he said with anticipatory delight.

Now that’s a Very Serious Hiker.

Mark Jenkins has hiked, hunted, climbed, or fished in all 15 wilderness areas in his home state of Wyoming.

The National Wilderness System

439 Forest Service

221 Bureau of Land Management

71 Fish and Wildlife Service

+61 National Park Service

758* total areas