The Source of All Things

'Paolo Marchesi'

All my dad has to do is answer the questions.

Just four simple questions. Only they aren’t that easy, because questions like this never are. We’re almost to The Temple, three days into the craggy maw of Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains, and he has no idea they’re coming. But I have them loaded, hot and explosive, like shells in a 30-30.

It’s July, and hotter than hell on the sage-covered slopes, where wildfires will char more than 130,000 acres by summer’s end. But we’re up high, climbing to 9,000 feet, and my dad thinks this heat feels cooler than the heat in Las Vegas, where he lives. Four days ago, he met me in Twin Falls, a town 140 miles south of here where I grew up, after driving north across Nevada, past other fires, including one on the Idaho border. The air is thin, the terrain rugged, and his body—64 years old, bowlegged, and 15 pounds overweight—seems tired and heavy to me. He struggled the last half-mile, stopping every few feet to catch his breath, adjust his pack, and tug on the big, wet circles that have formed under the armpits of his shirt, which reads Toot My Horn.

At sunrise this morning, we slid out of our bags, washed up, made breakfast, and caught a few fish. When we finally starting hiking, we climbed out of one basin and into another, inching up switchbacks sticky with lichen and loose with scree. When we came to the edge of one overlook, we saw smoke rising on the horizon from a fire that was crowning in the trees. And when we arrived at the lake with the dozen black frogs, we called it Holy Water Lake, because it was Sunday and we did feel a bit closer to God.

I know my dad is hurting, because I’m hurting, too—and not just my legs and lungs, or the blisters on the bottoms of my feet. We have barely spoken since we left the dock at Redfish Lake three days ago, left the boat and the worried Texans who looked at our 40-pound packs and said, “You’re going where?” I’m sure we seemed an odd pair: an old man and his—what was she? Daughter? Lover? Friend? When we stepped off the boat, I wanted to turn back. But The Temple was out here somewhere, and, besides, I still hadn’t decided if I was going to kill him outright or just walk him to death.

We continue climbing above Holy Water Lake until, a few hundred feet from a pass, we turn off the trail. In front of us is a cirque of smooth granite towers, sharp and fluted, like the turrets on the Mormon Tabernacle. The Temple shoots out of a giant boulder field. Loose rocks slide down vertical shafts and clatter to the ground. Quickly but carefully, my dad and I crab-walk across the jumbled blocks, insinuating ourselves into tight slots and willing our bodies to become lighter, so the boulders won’t shift beneath us and break our legs.

When we get to the wide, flat rock that looks like an altar, we stop. He slumps over, sips water, and chokes down a few bites of food. His eyes, the color of chocolate, begin to melt, and the corners of his mouth tremble, like he’s fighting off a frown.

Hunching next to him on the granite slab, I squint into his red-brown, sixteenth-Cherokee face. I dig into my pack and take out my tape recorder.

That’s when the questioning begins.

If we’d thought about it, back when I was a kid and my dad first joined the family, we might have nominated him for an award. Idaho Dad of the Year. Or the Elks Club Father’s Day prize. In the mid-’70s, after he married my mom and before the trouble set in, he built us an Idaho dream.

We had a RoadRunner camper, and every Friday between Memorial Day and the end of hunting season, my dad would leave his job at Van England’s store in Twin Falls, change into his camping clothes, and load his new family into his bright yellow Jeep Cherokee. While we sipped root beers and adjusted our things, he’d grease the ball on the tail of the Jeep, pull up the trailer steps, and ease us back until the hitch on the RoadRunner took hold. By the time the other dads on Richmond Drive were cracking their first weekend beers, we’d be chugging across the Perrine Bridge, past the lava flats with their searing heat, and approaching the cool, clean air of the Stanley Basin, where the Sawtooth Mountains top out at 10,800 feet.

If my dad loved being outside—hunting, hiking, and fishing Idaho’s pristine mountains and streams—he quickly taught me to love it, too. I was 4 and my brother was 8 the year my parents married, following a blistering whole-family courtship that included picnics at Shoshone Falls, ski trips to Soldier Mountain, and drive-in movies watched from bean bags in the back of my future dad’s 1949 Willys Jeep.

My real dad, a U.S. Navy man who held a kegger outside my mom’s hospital window the day I was born, died when I was 7 months old after an aneurysm exploded in his brain. My brother and I were too young to feel the gut-punch of his death—the disorienting, life-sucking loss that shook my mom so violently the doctors sedated her. But when lanky, bell-bottomed Donnie Lee walked through the door of our military-pension house, it was as if we remembered to miss something we’d never known. By the time my parents were married, the family honeymoon was already in full swing.

My new dad’s pride and joy—after his new family—was the RoadRunner he bought in 1976. On Thursdays, and sometimes as early as Wednesdays, he’d start loading it with supplies: bags of chips, Tang mixed with tea, and 12-packs of mini-cereals for my brother and me. One spring, he painted a yellow swoosh on the side to match his Cherokee. It came out looking like a streak of mucous, but we all told him we liked it anyway.

During the winter, when the roads were too snowy to pull the trailer, we feasted on elk steaks and venison stew made from the bucks my dad had harvested near Rock Creek and Porcupine Springs. But come mid-June, we were in full summer-camping mode.

In the long shadows of the Sawtooths, we built castles in the freshwater sand and swam out to a giant rock a few hundred feet from shore. Sometimes, other families came with us, and all the kids would hike together, searching for bird nests along wooden walkways that stretched over primordial wetlands, or climbing on top of beaver lodges before taking off our clothes and jumping into the murky ponds. At the time, the streams pouring out of Redfish Lake teemed with sockeye salmon on their way home from the mouth of the Pacific Ocean, 900 miles away.

As a little girl, I stared down at their rotting bodies, the wild look in their bulging eyes, and the long, hooked jawlines dotted with razor-sharp teeth. Though I couldn’t have articulated it then, I wondered what demon drove them to travel so far inland—without food or rest, for weeks—to decompose and die at Redfish Lake.

It’s early June, dusk, and the whole family is naked. We’ve stopped off at Russian John hot spring on our way to Redfish Lake.

Our clothes—my mom’s silk bra next to my size 6 flowered panties, big jeans and little jeans in a heap, a kid’s down vest, and a grown man’s hunting cap—are piled near the steaming pool that’s just past the ranger station on Highway 75. One by one, we slip into water that smells less like sulphur and more like infused sage. My parents slide down the algae-covered rock and laugh—at the urgency, the cold air, and the slight, acceptable indiscretion we are committing, uphill and just out of range of the car beams passing below.

We soak until the last rays of sun paint the mountains pink. We all scan the hillsides for deer. Spot one, and you earn a dollar: my new dad’s rule. A star—my new dad points it out—burns itself into view. “Wish on it,” he says, and we all do. When we begin to prune, we get out, tug on underwear and shirts, and rush back to the Jeep, where our black lab, Jigger, awaits.

When I think back to those early moments, I see a family, newly formed and on the front end of a great adventure. I see the four of us, back on the road after soaking in the springs. We are dried off and warming up, the blast of the heater drowning out Lynyrd Skynyrd on the radio. It’s dark now, and I have moved into the front seat. My dad and I are calling truckers on the CB using our handles, Pinky Tuscadero and Coyote. Outside the window, the Sawtooths rise into the night.

In my last, best memory of 1979, autumn light reflects off a golden Redfish Lake. Decaying aspen leaves smell good, in a sad, slowed-down way. Though I am only 8, these trips to the mountains have already become a foundation upon which I will build my identity. I’m telling my dad how I want to go into the Sawtooths, next summer maybe, on a real backpacking trip. He stomps out a cigarette and puts it in his pocket, then smiles tenderly. Because I don’t know what’s coming, I think this is how it will always be.

He takes my hand and leads me back to the trailer, where my mom and brother are fixing dinner. We crunch hard-shell tacos and guzzle cups of milk. Later, at the foldout table, we play cards—Spoons or Go Fish. My dad drinks beer and my brother begs for a sip. When I go to bed, my mom does, too, on the foldout couch directly below my foldout bunk. She reads for a while, then drifts off. I listen to my dad and brother. “Pair of jacks,” says my dad. And I fall asleep.

When I wake up, sandpaper is crawling on my skin. At least that’s what I think it is, until I feel hot breath against my cheek. The bunk bed where I am sleeping is two feet from the camper ceiling, and it’s coffin-dark. I can’t sit up, so I lay perfectly still, while my 8-year-old mind tries to understand sandpaper and beer-soaked breath. At first, I think someone has broken into the trailer. I must be alone, or my mom would jump up and scream. My dad would grab his rifle and start shooting. My brother would run out of the trailer and hide in the trees.

The sandpaper keeps moving, five round pieces the size of dimes. It scrapes my stomach, sliding along the top of my pajama pants, where it hesitates, then dips down. Completely disoriented, I try to scream, but no sound comes out. Holding my breath, I force myself to buck—away from the beer and abrasion, into the tightest ball I can make. The sandpaper stops moving. The breath grunts away from my face.

I’m swimming in tar. I will suffocate. I lay awake listening to the wind beat the trailer for hours.

The next morning, my dad and I walk to Fishhook Creek. I lead, he follows. I find a log, whitewashed and slippery, and inch across it to the center. My dad scoots behind me, lights a Camel, and sits down so that the soles of his black work boots just skim the ripples, which are metallic and bright.

I feet itchy and sick to my stomach, like I’ve been sunburned from the inside out. My dad puffs on his cigarette, exhaling streams of smoke that hang in the frosty air.

“I know what you’re thinking,” he says. “I know what you think that was.”

I consider asking him what he thinks I’m thinking, because what I am really wondering is how the salmon, struggling against the current below my feet, breathe in the murky eddies that disappear under the grassy bank. I am imagining, in some abstract and childish way, that I will dive in the river and let it flush me downstream. I hold my breath and let my dad continue. He puffs on his cigarette, then throws the butt into the creek.

“I mean it, Tracy,” he says. “I was only tucking you in.”

“What’s a pretty girl like you doing hiking alone?”

The guide at the cash register asks this when I step up to pay for my maps. It’s early October, 2006, and the thermometer reads 41°F. I’m standing at the counter at River One Outfitters in Stanley, Idaho, a tiny town at the base of the Sawtooths. Two months earlier, a congressman’s kid had gone missing on a solo hike. A search was mounted: helicopters, volunteer ground crews, and rangers all picking and flossing the granite teeth. There’d been no sign of him until a couple of days ago, when a corpse dog got onto—and then lost—a scent. This afternoon, I will hike eight miles into the Sawtooths.

“I’m prepared and conservative,” I tell the man as he rings up the maps. But it’s only a brave front. Two days ago, I flew to Boise, rented a car, and started driving east. On the freeway, the early October sun seemed too bright. But as I wound through Lowman, big stands of trees diffused the light, until the air took on a golden hue that I associate only with southern Idaho.

I didn’t plan to be driving down this road, concealing an open beer, listening to Zeppelin on the radio. I have a husband and two kids at home. It’s coming on three decades since my dad put his hands down my pants in the family trailer at Redfish Lake. I’ve been to therapy—years of it—and energy workers, astrologists, and priests. I’ve even been back to the Sawtooths, including once with my parents and kids. I thought it would be romantic to show the boys my favorite childhood place. They were babies, and they dug in the sand near the dock. We took off their diapers and let them wade among tiny flickering minnows that flashed like silver paperclips between their chubby legs.

Yesterday, I drove out of Sun Valley and pulled off the road at Russian John hot spring. I walked to the small, steaming pool where my family used to soak, and stood there imagining us naked under the stars. I didn’t get in. After an hour, I walked back to the car and drove toward Redfish Lake. I stopped at our favorite campsite near Fishhook Creek. And I found the spot where my dad and I once balanced on a log in the early autumn light.

Some people say you can heal yourself just by returning to the scene of a crime. They do that at the World Trade Center: put roses on the approximate spot a husband or sister landed after jumping out a window 100 stories up. I sat on the bank of Fishhook Creek for maybe half a day, thinking about the sandpaper, the cigarette in the water, and the chance my dad had to fess up.

He could have done it, told the truth right then and there, and avoided this whole damned mess. But he chose to pretend I was out of my head, a little girl confused by a scary dream. I can’t remember if he tried to hug me after we talked, but I know I instantly stopped trusting him.

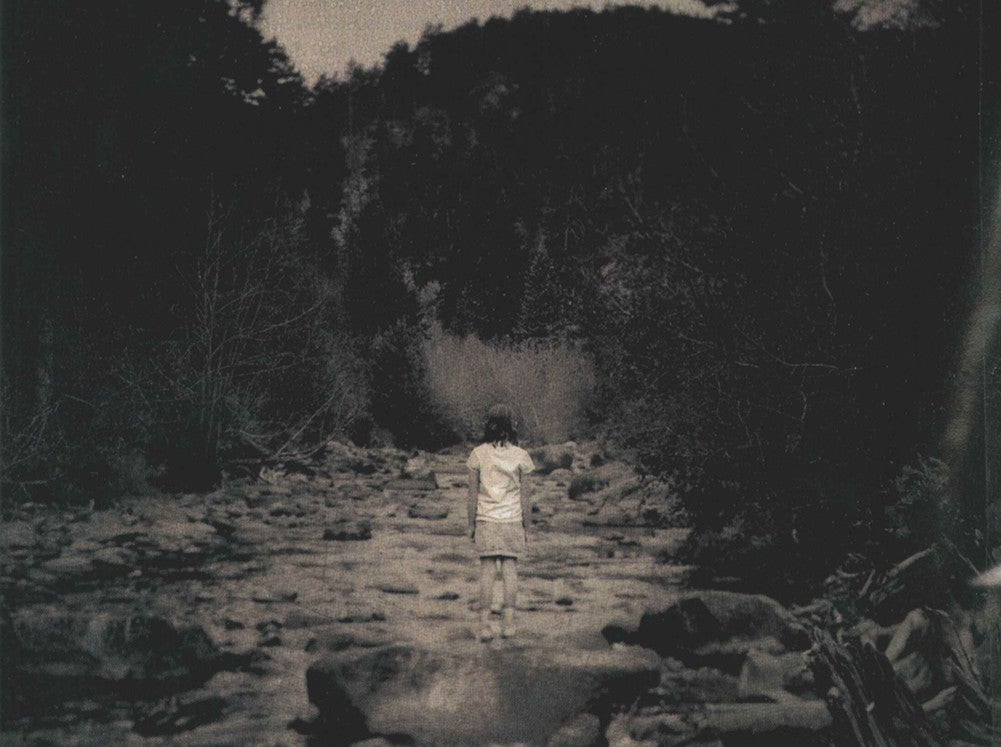

Sometimes, I take out a picture of myself from the early days at Redfish Lake. I am pigtailed and pink-cheeked, holding a Dixie Cup with a tadpole inside. I am beaming into the camera, proud of the new life I cradle in my hands.

I became a sad kid after that picture was taken. I’ve been a sad kid ever since.

I pack up my things and head toward the Sawtooths, where I hope to hike some happiness back into myself.

Looking back, there were no signs or indications to tell us my dad’s desire was unraveling inside him, dragging him away from my mother, toward me. For a long time after we stood on the log across Fishhook Creek, he didn’t touch me. But at age 12, as I began to climb the wave of puberty, he came back.

At first, he really was tucking me in—just thoroughly. But later, he let his hands wander. Sometimes, he watched me undress through the blinds he half-opened after dinner, when he went outside to smoke. When I sensed him in the backyard pretending to rake the grass, I would crouch and freeze, like a deer that tries to become invisible in broad daylight. Night after night, he ranged across my body, exploring this place and that. And sometimes he sat in a corner shining his flashlight on my exposed abdomen and thighs. The effect was so bewildering, I stopped knowing what to think.

For the growing-up victims of sexual abuse, every day becomes a test of personal perception. According to Darkness to Light, an international non-profit dedicated to child sexual-abuse awareness and prevention, one in four girls and one in six boys are sexually abused in the United States annually, and only 30 percent of all cases are reported. Most girls are molested by their fathers or stepfathers, and almost always inside the family home.

Even if my dad had stopped molesting me after that first night in the trailer, I would still carry wounds. Incest victims suffer from a wide range of maladjustments, including alcoholism, drug addiction, and promiscuity. Some experts believe that a child’s emotional growth is stunted at the age of the first attack, and that he or she will not begin to recover until adulthood, if ever. As adults, many survivors (or “thrivers,” as they’re now being called) find themselves unable to trust. They suffer from low or non-existent self-esteem. And they almost always have deeply conflicted feelings about sex.

As my dad frequented my bedroom, a creeping disintegration set in. It attacked my self-image, then spread, disease-like, to my sense of morality, ambition, and trust. I now think my entire family felt ill, though no one acknowledged why. We stopped camping, drew the curtains, and hardly ventured outside. Any connection I may have felt—to the mountains, my own potential, the world—began to erode.

Stacey, Tina, and I are speeding down Highway 75, passing a giant bottle of peach wine cooler between us and cranking Depeche Mode. I’m the only one old enough to drive. As we pass the turnoff for Fairfield and 70-mph wind rips through our hair, I turn to Tina and say, “Who’re you gonna screw tonight?”

It’s early fall. We take acid and smoke cigarettes. We lie to our parents and drive to Ketchum, across the Perrine Bridge, away from the dairy farms of Twin Falls, to a place where nobody knows us, except for the guys who’ve heard.

We wait outside a gas station begging people to buy us beer. In a couple of hours, we’ll go to a guy’s house whose name I don’t know, but who we met the last time we were here. I’ll stand outside on the porch, smoking a Camel Straight. Someone named Sam will walk out the door, push me against the wall, and smash his mouth against mine. By the end of the night, I will have consented to a certain kind of rape.

I started contemplating suicide on a regular basis when I was 14, as it dawned on me that no one was going to help—no matter what I said or did. My grandmother, a stoic with her own skeletons, refused to get involved. She listened to my reports at her kitchen table while she prepared elaborate duck or pheasant dinners for her hunting friends. But she never confronted my dad. And my mom, who’d already lost one husband, wore her denial like a heavy coat.

I can still remember the look on her face when I handed her a poem I’d written, one morning after my dad had been in my room. She read half of it—I can’t remember what it said—then folded the paper over. My dad was standing close enough in the kitchen to intercept the missive, but he didn’t see it. Why I didn’t give her the poem in private, I don’t know. But when she peered up, her eyes burned their own message back. “Please, please stop telling me this,” they said. And so, one night in the middle of August, 1985, I ran away.

It’s late, and I’m lying stomach-up on the living room floor, with one leg sticking out of a faded yellow nightgown with Tweety Bird on the front. I’m pretending to sleep as the wind screams across the lava flats, rattling the windows of our house. And my dad, dressed in a terrycloth robe and reeking of Old Spice, hovers a couple of inches above me, so that I can feel the heat coming off his chest.

I squirm, and he backs off. I roll over; he inches on. I jerk my head and lurch my body—still pretending to sleep, but showing him that I know what he’s doing and that it’s making me sick. My dad and I twist around like this until he decides I’m too restless to lay on top of tonight.

He gets up and stares at me, then goes outside for a smoke. When he comes in, he turns out the lights and heads to bed. I listen. Teeth brushed. Covers back. A little moan. Asleep.

When I hear him snoring, I put on my pink-and-black Vans and slip out the front door, careful not to let the wind slam it shut. I run to the end of our driveway and turn north, toward the Perrine Bridge. This is the night, I think, that everyone will remember, but no one will understand. I am running to the bridge, which stretches across the Snake River, nearly 500 feet in the air. When I get there, I will walk to the very center. I will climb on top of the railing. And I will jump.

The nights I was abused have become like dreams, some locked in a vault and others softened around the edges so that they sometimes seem almost tender. But there are others, terrifying aftershocks that flash out of nowhere—visceral as if they’d happened yesterday.

Lying in my sleeping bag a half-mile below Sawtooth Lake, I can’t get the bridge, the Tweety Bird nightgown, or my desperate 14-year-old face out of my head. It’s 3 a.m., and I’m staring at the roof of my tent. A thin layer of condensation has turned to ice, which keeps shearing off into my face.

Yesterday, I’d left the trailhead near Stanley and headed north, out of the showering aspen leaves and past the hillsides covered in scree. Even if I couldn’t find answers at Redfish Lake, I thought, I would still hike into my favorite mountains to clear my head. When I got to the dead ponderosa overlooking the limestone pipes, I’d taken a picture of myself and my pack. And when I reached the lake surrounded by snow-capped peaks, I’d tried to pitch my tent, but it was slushy and muddy and I started to cry.

Around 6 p.m., I packed up my things and turned down the trail. It’s okay to go to pieces, I thought, and then I started to run. I ran until I reached the lower basin, where I found strangers camped by a lake. Their closeness soothed me, so I laid out my gear, cooked some oatmeal, and went to bed. An ice cloud formed around the moon. The next 12 hours felt endless, like how I imagine solitary confinement would be.

The summer of 1985, I stood in the middle of the Perrine Bridge and didn’t jump. It might have been that the wind was howling so hard I couldn’t balance on the rail. I might have remembered the cat my brother told me he threw over, after he dipped it in gas—how it didn’t light on fire but seemed to scream. I stood there for a long time, and then I turned around and walked to the house of a friend whose mother was dating a cop.

The next day, the police knocked on my parents’ door and asked them for my things. When I later testified against my dad, I learned he had denied everything, then refused to take a lie-detector test. At the hearing, my mother wept quietly in the second row. I was moved into a foster home and became a ward of the state. My dad, who continued proclaiming his innocence, was sentenced to a year of abstinence—from me.

Somehow, in those darkest days when I was being shuttled from home to home and finally back to my mother, my parents decided that it would be best if they got back together. I moved to Oregon to live with a relative so my dad could go home. Several months later, when the year of our separation was over, my parents came to pick me up.

They thought they could jump-start our family and forcibly undo the damage that had been done. On the eve of their arrival in Oregon, my dad granted me a sparse admission over the phone—something like, “I did it. I’m sorry.” But it felt halfhearted, and I knew he was holding out. For the next year, I unleashed my hatred upon him, daring him to touch me so I could have him locked up. I mocked him for being an Idaho hick. And I meant it when I told him I’d kill him if he weren’t such a worthless fuck. A year after we reunited, when I was 16, I used my military pension to pay for boarding school in Michigan, planning never to return.

It almost worked. In following years, I extricated myself from my family by disappearing for months at a time. I went to places that didn’t have phones, like the Utah desert and Mexico. I enrolled in college several times—and dropped out when the urge to disappear became stronger than the need to fit in. But through it all, I continued to fragment.

Some people fall into the snakepit of their lives and reach their arms, like a baby, toward God. Others discover long-distance running or opium on a back street in Bali. When I realized that there was no escaping my pain, I turned my compass north and followed it until I reached a place where it was light all day.

Alaska. I went there after a friend told me that people in the 49th state partied till dawn in the endless gloaming of the Arctic summer. Our plan was to hike up glaciers and hang out on the banks of rivers loaded with salmon rumored to be as big as small dogs. We might work; we might not. The town we were headed to, McCarthy, didn’t have phone service and was accessible during the winter only by plane. It was a place where nobody knew you or cared if your story was true.

I took to Alaska like I’d been born there. By December 1994, my first winter, I was living in a 12-by-16-foot cabin, just off the McCarthy road in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. The cabin was eight hours northeast of Anchorage near the Canada border, with 10 million acres of wilderness out the front door. I was 24 years old—a baby. Even if they’d known where to look, my parents couldn’t have found me.

In the mornings, I wake up, stoke the barrel stove, and haul water from a pond after chopping a foot-thick hole in the ice. All day, I ski giant loops through stands of birch and black spruce on waxless cross-country boards. I glide along the moraine of a wide glacier that recedes at a geologic pace, skiing so hard my body sweats—even in thin layers when it’s -20°F. The miles rack up: 15, 30, 100. When I ski, some of the rage and sorrow seeps out of me.

Throughout the winter, I meet people who don’t care where I’ve come from, how long I’m staying, or when I’ll move on. My neighbors share homemade bread, store-bought cheese, and other prized possessions. We sit in wood-fired saunas drinking nearly-brewed beer, planning climbing trips, and watching the northern lights. I stare into their winter-rough faces and think I see something I can trust.

After McCarthy, I move to Fairbanks, the coldest spot on earth, to work for a sprint musher who spends $30,000 a year on 70 huskies that never win. I am in charge of something—four litters of puppies—for the first time in my life. I will make big decisions, like who will lead us out of the dog yard, who will get extra food, and who will live or die.

Solstices and equinoxes pass. By June 1996, I’m living in Talkeetna, on the southern edge of Denali National Park. I am building a cabin on two acres of land with a dog trail out back. I make friends who admire my tenacity. I start to believe they might be right. One day, a neighbor asks me to help with her dogs as she trains for the Iditarod. She, too, is brave and afraid; her boyfriend is dying of cancer. When I meet her at the start of another long race, she is crying, but she pushes 150 miles to the Kuskoquim River, then turns around and brings her dogs across the finish line. When I get home, I write a story about her on the back of a grocery bag, then take it to the local radio station and read it over the air. Weeks later, on the eve of the Iditarod, my story is broadcast on radio stations across the state, and months later wins an award. A light goes on in my head.

When I look back on the years I spent in Alaska, I see a more perfect version of myself emerging. I am stronger, more trusting, and kind. In 1997, I score a job as a backcountry ranger in Denali. I roam the park protecting grizzlies from people and people from bears. Against all odds, the hikers trust my advice. I’m promoted. One day, I find myself hiking with Bruce Babbit’s secretary, talking about the power of wilderness and how it changes lives—how it’s saving mine.

Mid-conversation, I flash to a moment my dad would have loved: soaking in the kettle ponds hidden in the muskeg below 20,320-foot Mt. McKinley. Maybe I think of him out of gratitude, for showing me how wilderness can shape and define. Maybe it’s just the hazy mellowing of distance and time. But by September, when I leave Alaska for the Lower 48, I am ready to embrace the world—and perhaps even my father.

It would be great if a few years in the wilderness could wipe away our pain. But of course it isn’t that easy. For a long time, through my late 20s and into my 30s, my dad and I airbrushed the abuse out of our family photo. We got so good at pretending, we almost convinced ourselves that we had moved on.

Truth is, my dad and I got on well together—in part because he tried hard to be good and normal again. He flew to Anchorage once, when I needed a partner to drive with down the Alcan Highway, too scared of the frost heaves and endless stretches of road between gas stations to do it alone. Over the years, he has given me cash and co-signed on cars. He has picked up the phone when I called to talk about my loneliness—or the weather—at 3 a.m. And it is he, not my mother, who has saved all of my stories, in big, black binders at home.

We have, as they say in psychotherapy circles, reconstructed our house of relationship. In 2000, he came to see the ultrasound of my first baby. When Scout was born, and 16 months later, Hatcher, my dad found a new reason to live. Indeed, my sons have become the brightest spot in his diminished life, and they love him acutely. He even babysits when my husband and I go skiing at Whistler for a week.

This easing of relations was good for my dad, and easy for me. But I still didn’t trust him—not completely.

“I can’t do this,” I tell my husband. “I can’t hold up the weight.” I am lying on a trail with my legs twisted in my mountain bike, and I can’t force myself to get up.

It’s Memorial Day, 2006. We are riding down Winiger Ridge when I miss a turn and grind into the dirt. The sun is shining on tight blue buds that will soon flower across hillsides covered in sage. The boys are at home with a babysitter. I am falling apart.

“What happened?” my husband asks. “You were flying back there. You looked good.”

Most things are looking good these days. After Alaska, I moved to Winter Park, Colorado, and skied five days a week. I kept writing, too, and landed a position at a big magazine. I live on two wooded acres at 8,500 feet on the outskirts of Boulder. My family hikes out the front door. On summer nights, we sit on our deck and watch satellites cross the sky, and in the winter, with snow blanketing the ground, we listen to a quiet so vast it creates its own sound.

And yet the weight had crept back, so heavy I felt it would crush me.

It started last spring, after an exhausting stretch of work-related travel. I felt wretched and broke out in cold sores. When I went for a check-up, a physician’s assistant prescribed the antidepressant Lexapro, and I took it even though I wasn’t depressed.

Instead of making me feel better, the pills made me groggy, irritable, and profoundly morose. After a week, I stopped sleeping almost completely and couldn’t concentrate. I laid in bed staring at the ceiling. A bobcat wandered through the backyard; I didn’t try to get up. I couldn’t understand why I was feeling so down. I kept saying, My life is a million times better than it should have been. And then I thought about my dad, and my head began to hurt.

In recent years, his apologies had become more frequent, though he still talked euphemistically about “hurting me” or “making my life hard.” He suffered openly when I refused to let him give me away at my wedding, and has cried man-size tears while we’ve sat at breakfast joints and bar stools across the West. But he never truly came clean—to me or anyone else in the family—about the extent of my abuse. No one knew the capacity for incest he still had. I couldn’t be sure he didn’t harbor fantasies about me. And I began to worry about what he could do to my kids.

In the haze of my antidepressant detox, I decided I had to go back to the Sawtooths. I believed I could find answers there, at the scene of the crime.

It didn’t work. I laid in my sleeping bag at Sawtooth Lake. I waited for the ice cloud to burn off the moon. By the time the sun spread over the peaks, I knew I couldn’t reconstruct the past by myself. I needed my dad to complete the story. And I knew we could only do it in the one place that had formed us both.

My dad was born on March 12, 1943. His mom was 17. One day, her husband went deer hunting in the mountains above their Colorado home. She wanted to go with him; she’d bring the baby. He said, “No, a woman’s place is in the home,” and she divorced him because of that.

A year later, my grandmother married Baby Donnie a new father. He worked as a wire-stringer for the phone company. The entire family—Les, Lorraine, and little Donnie Lee—traipsed up and down the Rockies eavesdropping on people’s conversations zzztzing through the line. By the time my dad was 6, his family had lived in seven states, moving across the country like well-dressed gypsies.

Life was good on the road. My dad slept in hotels and ate out every night. He was resourceful and obedient. He made boats that he floated down gutters along empty backroads in New Mexico, Arizona, and Idaho. And when he was 5, he was sodomized.

It was an older cousin at a family gathering. My dad says the kids were just being kids. And besides, it only went on for a couple of years. He doesn’t think he was mentally scarred, but admits it formed his attitude toward sex. “It showed me sex wasn’t something you should be afraid of,” he told me once. “It was how you showed your love.”

I’m afraid. My dad and I sit at the picnic table on the far side of Redfish Lake. The boat has left, and so have the worried Texans, who didn’t offer to help with our packs but waved as they motored away.

Today, we will hike through the yarrow and sage, stopping every 10 minutes for my dad to catch his breath. When we get to the slippery rocks in the river, I’ll take off my boots and slide 50 feet into the emerald pool. And when we pass the giant face under the Elephant’s Perch, I’ll realize that this is going to take more out of us than I had expected.

After the Lexapro, and the vision, and the truncated solo that ended with a sleepless night, I called my dad and asked, “Will you come to the Sawtooths with me?” I was in the loft, at home, and felt overheated, confused, and slightly brave. He said, “Yes. Of course. I think so. Let me think about it.”

Now we are heading into a mountain range that looks imposing and mean. When I called my dad months ago, this trip seemed noble, necessary, and in a twisted way, fun. This will be the first and last time we go on a multiday backpacking trip, just the two of us, in the place we love most on earth.

I’m scared because when I am with my dad I am 8 years old. We will walk for days up forested valleys. We will camp in places so lovely we’ll want to weep. Fish will rise to the surface of a dozen glassy lakes. And he might try to lie on top of me when I fall asleep.

“I’ve made some rules for myself,” he announces, then rattles them off. “I won’t ask questions. I won’t speak out of turn. I won’t be vulgar or too descriptive. I won’t get pissed off at you.” I stare at him. You won’t get pissed at me? What the hell is wrong with you? Then I check off the questions I will ask him when we get to The Temple, three days from here.

When did it start?

When did it end?

How many times did you do it?

And why?

Two hours later, we are inching our way up the dusty switchbacks through spruce trees and lodgepole pine. My dad drags his legs. A week ago, at a party in Utah, he tried dangling from a rope swing that hung out of a tree. When he caught the edge of his shoe on a root, he held on and scraped himself over some rocks, rubbing the flesh off of his knees. Now the scabs are deep, dark red, and crack open when he walks.

We continue like this until we reach the sign for Alpine Lake, where we’ll spend our first night. We’ve hiked five miles and gained just 1,000 feet, but our campsite is still a mile away and another 800 feet higher. My dad looks weary, like he could lie down right here with his pack on and sleep until morning. I make him eat a Clif Bar and we load up, the trail becoming steeper with every step.

At the fifth switchback, my dad has fallen 10 minutes behind. I consider waiting, then clip along at my own pace. I know my dad is getting older and is out of shape, and that in his condition he could be back there somewhere having a heart attack. I keep walking until I reach Alpine Lake.

That night, after dinner, I change my clothes and worm into my sleeping bag. My dad heads to the lake and casts for rainbows. I scoot my sleeping pad as far from his as possible, until I’m lying in the corner of the tent.

I know it’s weird that we didn’t bring two tents, but this is my dad, my father, who took up the job of caring for us voluntarily when he married my mom. Like most little girls, I worshipped my dad. We snuggled in my parents’ double-wide Cabela’s sleeping bag. He let me brush and blow-dry his hair. And I don’t know how many hours I watched him load shotgun shells in the basement of our house.

I do know that any self-respecting woman would demand her own space. And yet my weakness isn’t just a longing for simpler times. As I have learned about my dad’s abuse, I’ve begun to see him in a different light. Once, after a bluegrass show when he imbibed too much, he cried in the car and told me that he would give anything if he could go back and make things right. For better or worse, I believed him. And before all that—before everything—there were the years at Redfish Lake. I hold those early memories carefully, like pressed wildflowers that, if jostled, would crumble to dust.

Still, the tent is an uncomfortable place, and so this too becomes a crime. One of backpacking’s greatest virtues is that it makes instant bedfellows out of strangers and friends. When else do we lie under a star-filled sky separated by a few cubic inches of down? In the tents of my past, I have fallen in love and whispered my greatest longings and dreams. My tentmates and I have laughed until we peed our pants, knowing that in the morning, we will have created a shared history at 10,000 feet. Herein lies one of backpacking’s true beauties, beyond the stunning vistas and close encounters with wildlife: It creates an intimacy that transcends normal friendship and even eludes some of the best marriages.

This is the first time my dad and I will lie shoulder-to-shoulder since I was a teenager in Twin Falls. I will wear all of my clothes and never really fall asleep.

The next morning, we pack up, eat breakfast, and head back down the switchbacks, which murder our knees. As we walk, my dad fills the silence I create. He reminisces about bird hunting with his friend Gary Mitchell and fishing for the eight-pound trout that used to feed on freshwater shrimp in Richfield Canal.

He sifts through his better memories, until we come to a big log on the side of the trail, where we break out our lunch. Then this:

“I was 16 the first time I killed a deer,” he says. A 4-point buck “that would have been an 8-point by Eastern standards” walked into the crosshairs of his gun. When he pulled the trigger, he got so excited he started shaking uncontrollably. It was buck fever, and he had it bad.

“You can hardly grab your breath,” he says, grinning mischievously. “Just knowing that you can actually kill something, it’s the height of excitement. It makes you weak in the knees.”

My dad scans the trees, inhales deeply, and smiles. I realize that I haven’t seen him in this setting, surrounded by rivers and trees, in years. In 1990, my parents moved to Nevada. They sold the camper and packed my dad’s shot-loading equipment in a box. One summer a few years later, he came to visit while I was living in Jackson, Wyoming. He said he’d bring his fly rod and camping stuff. When he arrived, he was under-dressed in a light wind shell and braced himself against the cold. We went to the Snake River and he sat down in a heap.

“Break out your rod, Dad,” I said. But he couldn’t. He’d forgotten to pack it.

My dad looks up the trail. “I got away from shooting does,” he says, “after I killed one with a fawn.” The fawn’s cries echoed through the South Hills, and he couldn’t stand the sound. So he put a bullet in its head.

We chat, nibble on sausage, and dry our sweaty shirts in the breeze.

Two hours later, we take off our boots and wade into a bottom—clear lake. The silence is back, bigger than it has been all week. A giant rock leads into the water, then drops off like a cliff. The fish are rising now, and my dad follows the ripples out to the edge of the lake. Watching him, I rehearse different ways to interrogate.

So, Dad. When was the first time you…abused me? (Too clinical. This isn’t an after-school special.)

…touched me? (Too real-time.)

…completely fucked up my bearings?

Yes, that’s it. That’s how I’ll start the conversation when we get to The Temple and he’s so tired he can’t defend himself. I join him by the water. He looks up and smiles. “Feels warm enough to swim.”

My dad collapses the second we reach the altar. We’re in the middle of the boulder field that threatened to break us in half. Sweat drenches his entire torso. His face looks punched and weak. Before we left the trail, he stopped to peer up at the stone minarets surrounding The Temple. I heard the bones cracking as he craned his neck. “Beautimus,” he whispered.

I crouch down, slightly behind him, and dig in my pack. This is the moment I’ve been waiting for: when the truth will shine down upon us and the heavens break open under the weight of a million dirty-white doves. I take out my dictaphone, test the battery, and push record. The entire conversation will last 13 minutes.

The Truth (a one-act play)

[The lights come up on a rock in the middle of a boulder field. Don, an attractive man in his mid-60s, sits slightly in front of his daughter, Tracy. She holds a reporter’s tape recorder in front of his face.]

Tracy: [Fidgeting; tugging at her shorts.] So…this is going to be hard.

Don: It’s okay.

Tracy: [Hands spread on the rock, absorbing its heat.] All I have are four questions. And I don’t want to know details. Because I know. I was there. And so what is important to me is to know your version of the truth.

Don: [Nodding, looking down.]

Tracy: Okay. When did it start?

Don: [Clearing his throat, composed.] On a camping trip up here at Redfish. I had been drinking. I lied. I was tucking you in. My hands went to a spot, which surprised me, and I kept them there. But the severity—it wasn’t that often at that age. Just periodically.

Tracy: [Agitated.] But I was 8. Couldn’t you see what that did to me and say, “Oh my God, oh my God, I did that. That was a mistake”?

Don: [Calmly; choosing his words.] A person who does what I did…you make things up. You don’t think of the other person. You just need that closeness. If I had ever known how it would have affected you, I probably would done something completely different.

Tracy: [Still agitated.] So…that day on the log. I wasn’t upset?

Don: I don’t think so. I don’t remember. I was trying to cover things up. I had feelings for you. I thought of you as my fishing buddy. The only thing I could do was lie. I wasn’t thinking of you.

Tracy: Just so you know…in case you were wondering…I was thinking about what would happen if I jumped in the river and died. [Starting to cry.] I was 8. That’s so fucked up.

Don: [Tenderly.] No, it isn’t.

Tracy: [Sadly.] Yes, it is. When you’re 8 years old, you’re a little kid. It wasn’t a physical thing?

Don: Not then, but later I was put in a position where you were going through puberty. This was your teen years, you were probably 12 or 13. Your mother stopped being intimate. I leaned to you for closeness.

Tracy: [Putting her hands up as if to say “stop.”] Okay, okay. So mom wasn’t interested in being intimate? Why didn’t you go have an affair?

Don: [Nodding.] That’s what I shoulda done. By all means.

[A break. Tracy takes a drink of water, shakes her head. Stands up, sits down. Don looks across the valley. A hawk skims the trees.]

Tracy: Okay. [Sigh.] Now, how many times did it happen? In various degrees of whatever it was. Coming into my room…whatever that was. Till it ended.

Don: Between 25 and 50 times maybe. You know, I never kept track.

[A long silence.]

Tracy: [Fighting tears.] You must have felt like shit about that, right? I mean, I didn’t want that, right? [Sitting down, hugging her legs to her chest.] I wasn’t a willing accomplice…right?

Don: You weren’t a willing accomplice. I didn’t expect you to be willing. I really felt screwed up. Why would I jeopardize my family like that? And I’m not using this as an excuse, but I was abused when I was real young.

Tracy: Did you do it to Chris?

Don: No, no. It’s never boys.

Tracy: [Her eyes squeeze shut, her face registering fear.] Who else then?

Don: I haven’t had those feelings for anybody, ever since.

Tracy: Since when?

Don: Since you. It ended when you left, when you ran away.

[They’re both crying now. The wind has picked up.]

Tracy: So one day it was just…over?

Don: No, it’s never over. You have those feelings, but they’re just like this tape. It replays but you learn how to stop it. You learn how.

Some people believe the truth will set you free. I think that’s too easy. When my dad made his confession at The Temple, a weight lifted, but only long enough for me to take a deep breath.

After 20 years of second guessing my own memory, feeling ashamed of my sexuality, and aching for the confirmation that others have always denied, I finally had proof. But the victory wasn’t entirely sweet. My dad’s confession also horrified me. I’d always hated that he put his twisted desire before a small girl’s suffering. Now that I had learned how often it had happened—50 nights lost, never to be regained—a new sadness gripped me. And yet, things had changed for the better at The Temple. By confessing, my dad has given me something back—power, the anticipation of a fuller future, maybe even my life. And finally, after all of these years in the wilderness, I’m might find the strength to truly forgive him.

In the dry, wild heart of southern Idaho, past Russian John hot spring and the ranger station on Highway 75, there is a small wooden sign, barely visible from the overlook on Galena Pass. Through a camera lens you might not even notice it, dwarfed as it is by the Sawtooth Mountains, which spread out before you and fall away somewhere in Utah. But if you know where to look, you’ll find the sign, and below it, a tiny spring buried in overgrown grass. These are the headwaters of the River of No Return, a creek that seeps out of the earth, gathers volume and speed, and becomes so fierce 100 miles from here that it cuts a trench in the earth 1,000 feet deep.

People say the river was named this because the current is so strong it’s impossible to travel upstream. But when I was a little girl, I stood on the banks watching sockeye struggling toward their ancient spawning grounds at Redfish Lake. Nine hundred miles from their starting point in the Pacific, they arrived redder than overripe tomatoes, their flesh already breaking apart.

In the early 1970s, thousands of fish returned here to lay their eggs and die. Then we put in dams along the Columbia and Snake Rivers. By 1975, eight concrete barriers stood between the Pacific Ocean and Redfish Lake, and by 1995, the sockeye population had dwindled to none.

Many people took this as a sign: that the world had become too corrupt for something so pure as native salmon to exist. I might have believed that, too, until last summer, when four Snake River sockeye made it home.

Tracy Ross published her full-length memoir, The Source of All Things, in 2012.