If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

‘Surviving The Trail’ Is the New Guidebook Even Our Editor Needed

(Photo: Emma Veidt)

Although quite rare, unintentional death is a tragic possibility on hiking trails. Between 2014 and 2019, the National Park Service reported 1,080 unintentional fatalities, resulting from accidental drownings, falls, hypothermia, thermal burns, and more. That’s a small percentage of hikers overall, but to prevent adding to it, it’s important to know the risks of outdoor recreation. Too often at Backpacker do we cover stories about hikers all throughout the country who drowned, died of hypothermia, or perished due to heat exhaustion.

Arming yourself with know-how is the best way to confidently go into the backcountry without fear. There are thousands of books out there on the topic, but many are outdated and more are extremely dry. However, Surviving the Trail: Five Essential Skills To Prepare Every Hiker For Adventure’s Most Common Perils, published earlier this month by Falcon Guides, breaks down common backcountry dangers in an easy-to-follow, relatable way. The author, Dr. Robert Scanlon, is a board-certified pulmonary medicine and critical care physician with over 20 years of practice, yet the book isn’t saturated with medical jargon. He writes in a way that the average hiker can understand.

Dr. Scanlon’s mantra is, “preparation is the ultimate survival skill.” As hinted in the book’s title, he emphasizes the five skills that every hiker should master to tackle the most common dangers outdoors: Hydration Strategy, Weather and Managing Body Temperature, Crossing Waterways, Awareness Of Heights and the Risk Of Falling, and Land Navigation. Each section uses real-life examples, critical visual references, and scientific explanations that I (a non-scientist who once got a C+ in chemistry) can actually understand. Here’s a peek inside.

Skill 1: Hydration Strategy

A common survival axiom is “drink 1 liter of water for every 5 miles on the trail.” That guideline, however, is short-sighted. What if it’s humid? What if you’re a slow hiker? What if the terrain is steep? These factors—and more—play into how much water you’ll need on trail. Dr. Scanlon created a chart that outlines how much water you should consume per hour on the trail based on pace, terrain, forecasted temperature, and humidity. Turns out that, depending on these conditions, your fluid needs could range from 16 ounces to 40 ounces per hour. I’ve grown reliant on the 5 miles per liter ratio, but now I’ll consider all the variables when packing for a hike.

Similar Reads

Skill 2: Weather and Managing Body Temperature

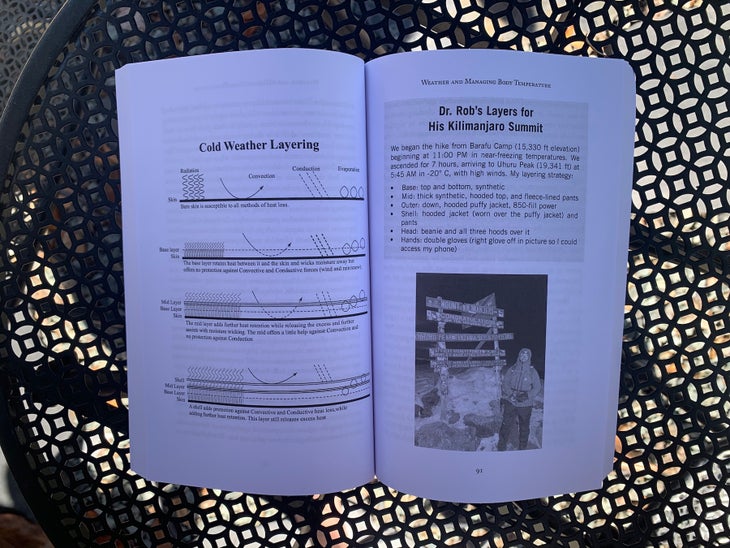

They say there are three learning styles: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. I say there’s a fourth: learning through examples. Dr. Scanlon humanizes complex topics by bringing up scenarios where he himself had to use survival skills in a real-life incident. These anecdotes were especially salient in the weather and body temperature section of the book.

Here, Dr. Scanlon details what it was like to develop an early case of moderate hypothermia due to monsoon-like rains on Kilimanjaro, plus how he layered his clothes to prevent it on his summit push in windy, near-freezing temps. We’re learning from someone who has certainly been there in Surviving The Trail.

Skill 3: Crossing Waterways

Even though I’m a Backpacker editor, I consider myself average at water crossings. Most of my backpacking occurs in southern California, where we’re lucky just to get a reliable puddle to filter water during the summer. It’s been a while since I’ve needed to actually ford a stream.

In this chapter, it was as if Dr. Scanlon was one step ahead of me the whole time. Any “what if” I could think of while imagining crossing rushing water, he addressed in a hypothetical scenario, explaining how to avoid or survive it. Because of this, Surviving The Trail quelled some of my anxieties about backpacking in wetter landscapes. He even included helpful resources to research current water depth levels, which is something that every hiker should do before hitting the trail.

Skill 4: Awareness Of Heights and the Risk Of Falling

On a rooty, rocky trail, minor trips and falls are common occurrences. Most of the resulting scrapes require minor TLC, but large falls—such as slipping off cliffsides or overlooks—are one of the more common causes of deaths in the backcountry, according to Dr. Scanlon. They account for 20 percent of national parks deaths and are more common in parks with sheer dropoffs like Grand Canyon and Yosemite.

He addresses common risk factors (did you know that those who engage in risky behavior are likely to be male, over 21 years old, and traveling in a group?) plus, with sections like “The Fatal Selfie,” he also addresses risks that are unique to the modern era. For the medically curious, this section also explains how rapid deceleration, such as landing after a significant fall, causes internal whiplash that fatally damages bones and crucial organs. Although medical facts like that aren’t necessarily going to be the things that save me in a pinch, I feel smarter and better off as a hiker knowing them.

Skill 5: Land Navigation

When it comes to knowledge retention, map and compass skills are the hardest for me. Years ago, I learned everything. Now, thanks to a reliance on digital maps, I would not trust my ability to recall how to adjust for declination, certainly not in a panicked survival situation.

It’s easy to assume that these skills belong in a crypt with other pre-GPS relics. But, batteries die, signals can be spotty, and online maps sometimes don’t have the same topographic detail as paper ones. So it’s crucial for all hikers to learn how to manage both navigation methods, and this book is an excellent way to start. Dr. Scanlon takes his time in this section, the longest in the book by far, for clear step-by-step instructions (with pictures) that outline all of those easily perishable compass techniques. This includes accounting for the difference between magnetic north and true north, finding your location on a map, and some habits that Dr. Scanlon personally uses to hone these skills.