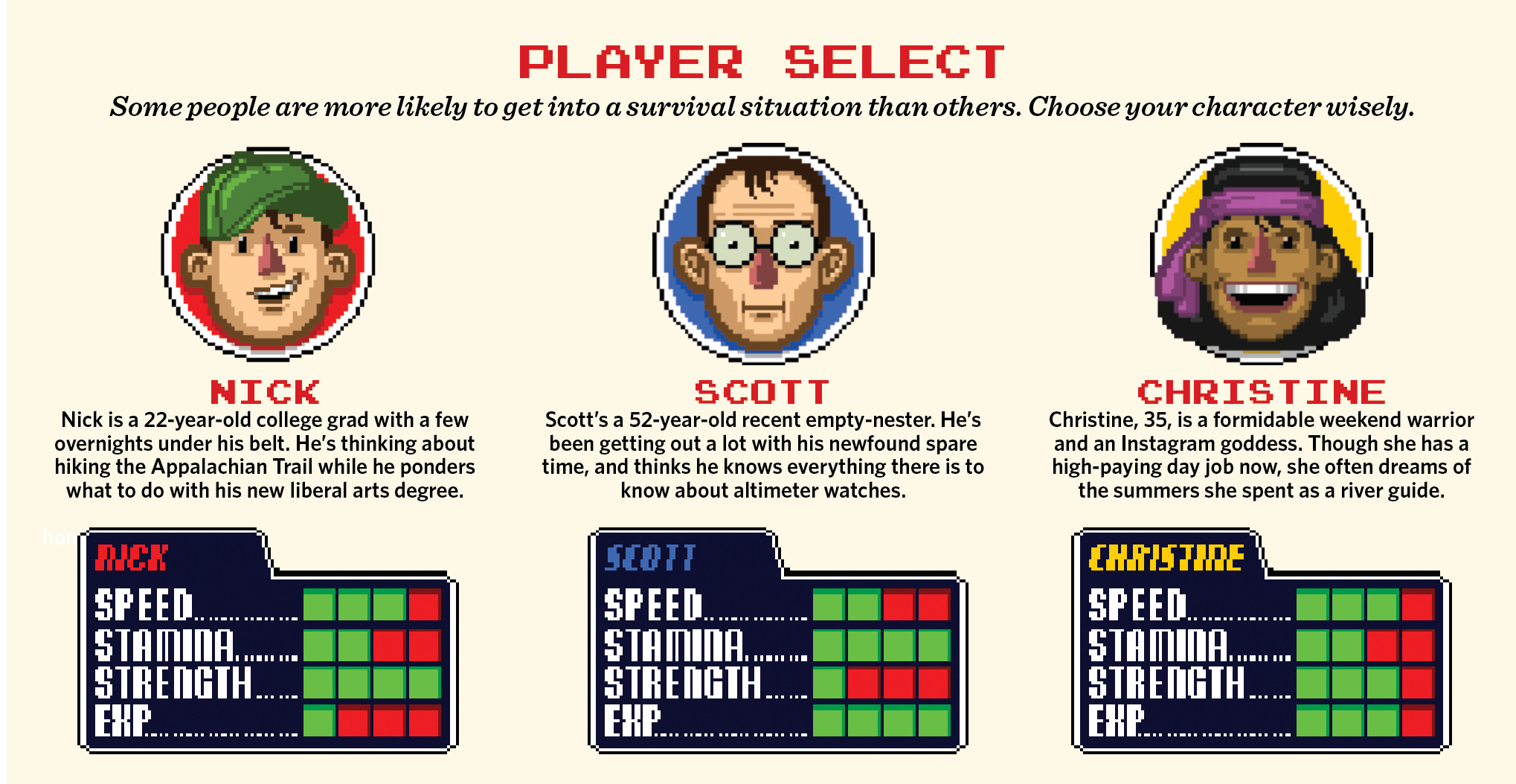

Could You Survive?

Level 1: Surviving the First Hour

Lightning. Flash floods. Falls. To advance in this game, you first must survive the immediate threats. Here’s how to think fast, avoid panic, and make the right decisions in the critical first hour.

It Happened to Me: Struck by Lightning

Mary Chandler, 29, and three friends got caught in a lightning storm on a Colorado Fourteener in 2015.

Where’s Will? I woke up on the side of Mt. Bierstadt, soaked, shaking, and buzzing with electricity. I could smell burning hair, and my hiking partners—including my fiancé Will—were gone.

It was a beautiful June morning, and I’d wanted to make the most of it. Will and our friends Jonathan and Matt decided to grab our dogs and climb Bierstadt, an easy Fourteener near Denver, and set off around 7 a.m. I always wonder what would have happened if we’d left just 30 minutes earlier.

We reached the summit under partly cloudy skies, took some photos, and started down. Then a dark cloud rolled in. It started hailing. Suddenly, a flash of white light swallowed everything.

Next thing I knew, a stranger was wrapping my head in his T-shirt. I was confused and panicked, and my heart was beating so fast I thought it was going to rocket out of my chest. My forehead was damp with blood. Did I fall? I scanned the scene for Will. He was OK, sitting and surrounded by other hikers, as I was. He must have fallen, too, I thought hazily.

Then I heard Jonathan screaming. He was badly injured, and his dog, Rambo, was dead. Thunder clapped in the distance. Only then did it occur to me: We were struck by lightning.

Storms kept the helicopters away, so we hiked down. Matt, Will, and I walked on our own, but a group of hikers had to help Jonathan, who’d taken the brunt of the strike and had a bad head wound.

We all suffered spotty vision and migraines for months after the strike. Now those symptoms have faded, but the lesson never will: Everything can change in an instant. —As told to Morgan Mcfall-Johnsen

How to Beat Panic

Your brain is lazy. Or, more charitably, your brain is efficient; it learns to do something, then codes it in what neuroscientists call a “script”—a task you can do without thinking, like tying your shoes. The trouble with scripts?

“According to the research, when you’re put under extreme stress, you’re not going to invent new behaviors to deal with it. You’re going to do what you’ve done in the past,” says Laurence Gonzales, author of Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why. When you panic, your brain essentially turns off your prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive decision-making, and looks for shortcuts. And those automatic reactions—like lunging for a dropped camera during a river crossing—can be dangerous.

To skip the autopilot phase, Gonzales recommends practicing some neurological exercises, like tying your shoes a new way every day or moving your cups to a different cabinet. The more you can avoid creating scripts, the faster your brain will redirect to the prefrontal cortex when you’re in trouble—giving you back precious seconds that could save your life.

Quiz: Test Your Survival Skills

In a true survival situation, any mistake can be fatal. How would you deal?

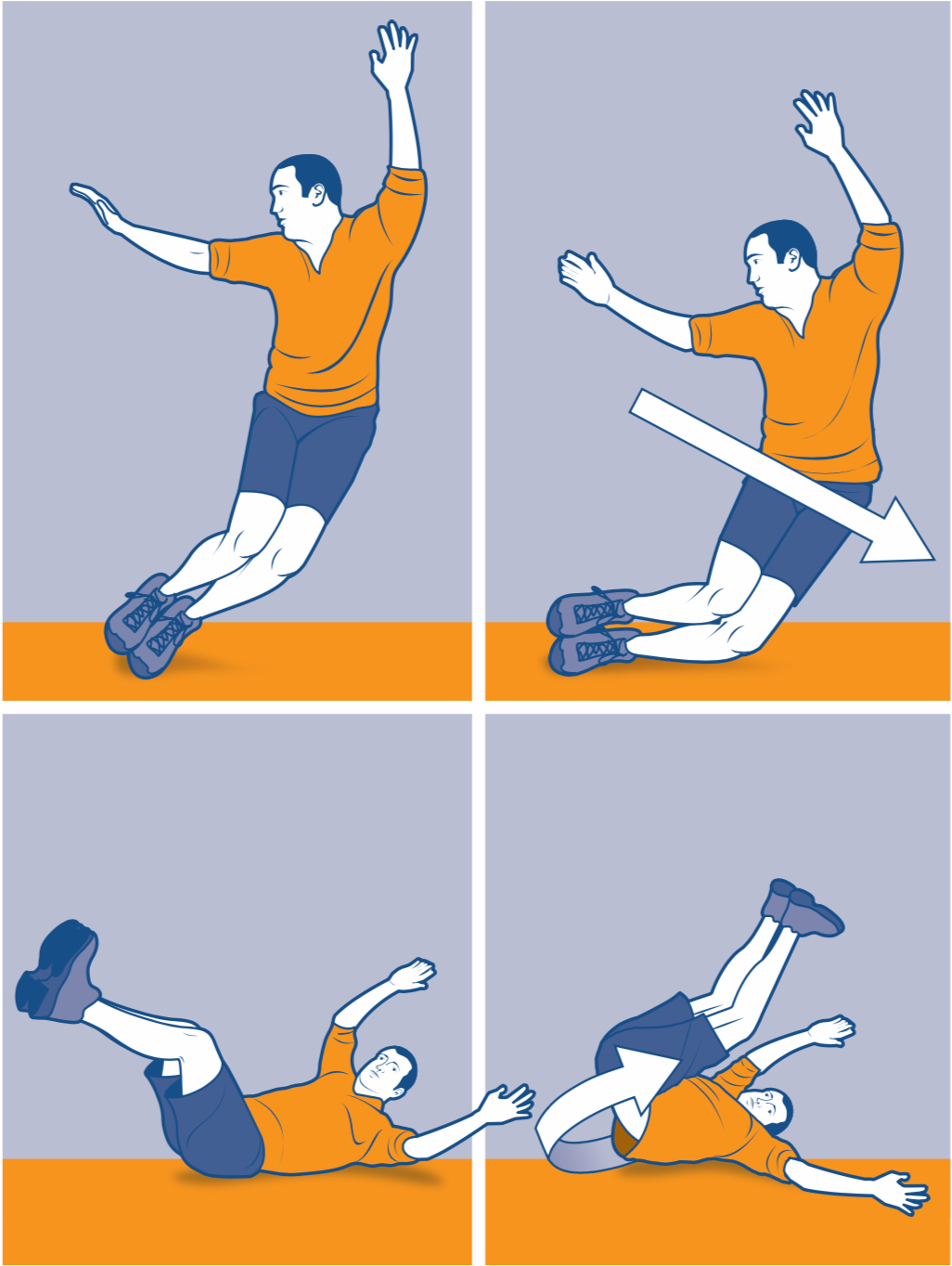

Key Skill: Roll Out of a Fall

After drowning, falling is the number one killer in the backcountry, and even a non-lethal plummet can leave you with broken bones. To improve your odds, relax your joints and take the hit like a paratrooper, rolling away the momentum and letting your thighs and shoulders absorb the brunt of the impact.

Survive a Bear Encounter

Reality check: Fatal bruin attacks are pretty rare. There were 46 reported occurrences in North America from 2000 to 2017, or an average of three per year. But we get it; you don’t want stats, you want to be prepared. So here’s how to handle a bad-news bear.

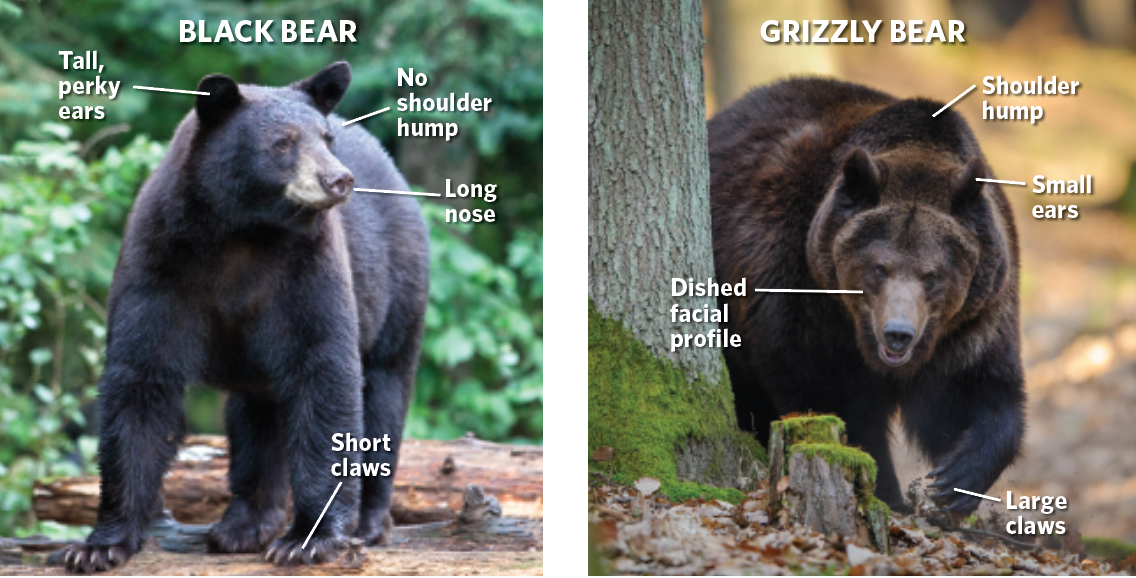

Color and size can be misleading. Black bears often sport a brownish coat, and young grizzlies can be small. Knowing the difference is important: Grizzlies have been known to attack humans to defend their young, which means backing off or playing dead could spare you a mother’s wrath. Black bears are more often responsible for predatory attacks—meaning playing dead for too long could get you eaten. Learn the right identification to help you predict the bear’s next move.

Fight Right

If you know a bear’s not acting defensively, or if you’re playing dead and it starts chewing on you, it’s time to start swinging. Aim for the eyes and nose.

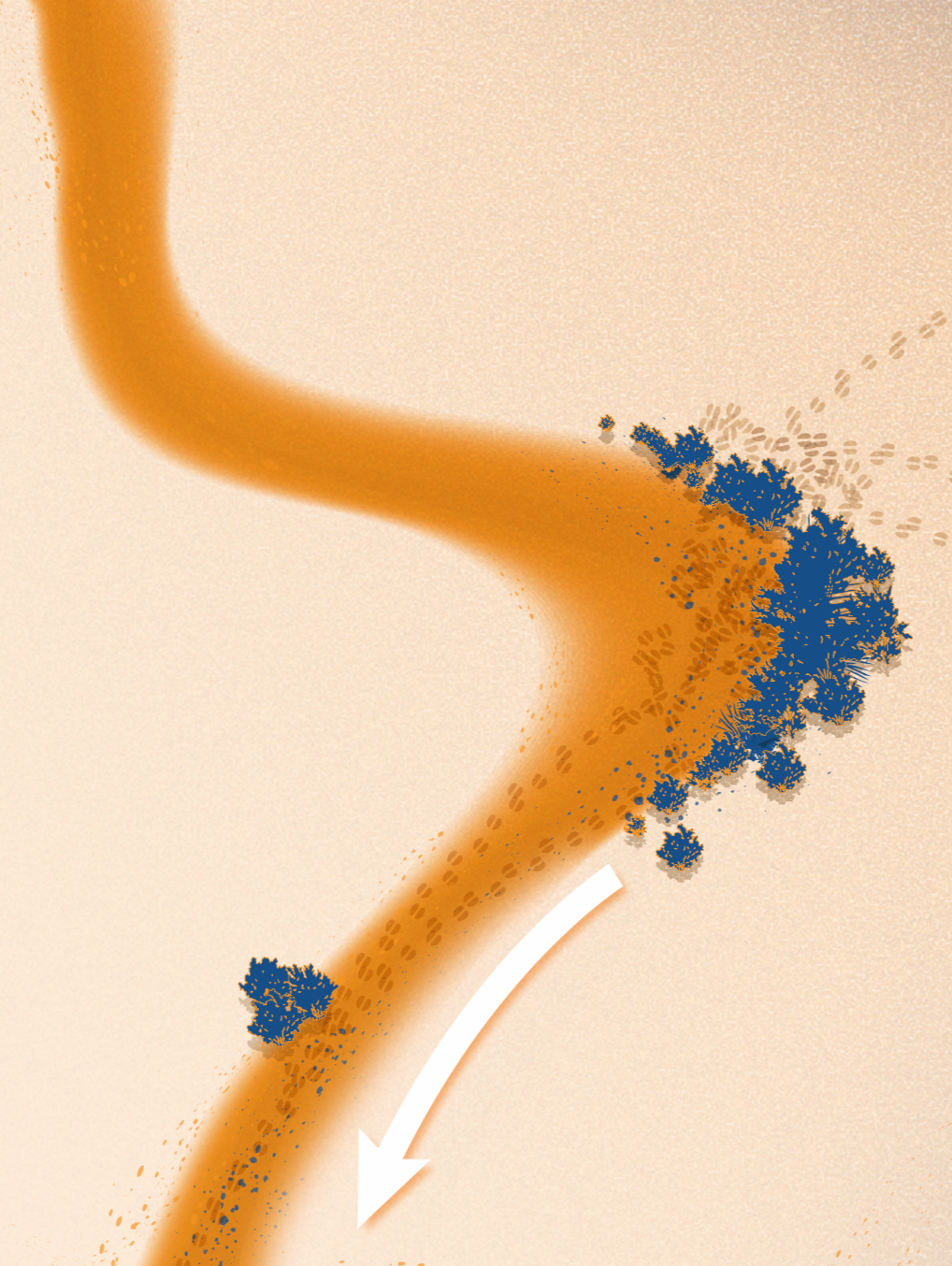

Survive an Avalanche

On average, there are 28 avy fatalities each winter in the U.S. Nine of those are hikers, snowshoers, and skiers. While careful planning and navigation can prevent most accidents, sometimes the slope still rips.

Learn the basics. First things first: Get certified with an AIARE Level 1 course, which offers instruction on snowpack and terrain hazards. Pack a beacon, probe, and shovel into the backcountry—and know how to use them.

Avoid steeps. Don’t cross on or below slopes between 30 and 45 degrees—those are the ones most likely to let loose.

Get to stable ground. If the snow starts sliding under (or above) you, try to escape the avalanche path and reach for a tree or plant a ski pole or ice axe beyond the break line. Move fast—slabs can hit 80 mph within five seconds. Far from the fracture? Start ditching potential anchors like skis and poles.

Stay above the snow. Only 40 percent of victims survive after being fully buried for 15 minutes. Keep your pack—bigger objects tend to “float” in an avalanche, and it may protect your backside. Fight to keep your head above the surface, using your arms to “swim” upward.

Create an air pocket. If you’re caught in the flow and likely to be buried, tuck your face into the crook of your elbow (do this before the snow stops moving—once it does, it’ll set like quick-dry concrete). If you can thrust your hand upward, it’ll make you easier to find, but digging yourself out isn’t an option; save your energy, and rely on your partners for rescue.

Key Skill: Escape a Tree Well

Skiers and snowshoers who fall in often end up head first and can suffocate within 15 minutes.

1) When sliding into the well, grab the tree’s branches or trunk to remain upright.

2) Too late? Move your head slowly from side to side to look for air pockets. Avoid sloughing in more snow.

3) Shout for help. If you’re alone, your chances are slim. Try to pop out of your skis or snowshoes and slowly and methodically feel for a branch or trunk. Grab on, try to shuffle your feet sideways, and haul yourself upright.

Expert Advice: Be Aware

“Remember, a lot of these crises happen to people who aren’t aware of their surroundings. You’ve taken the responsibility to put all kinds of stuff in your pack, but ask yourself: Have you taken the time to turn on all the mental switches? It isn’t enough to just know that flash floods, predators, and potential hazards exist. You need to move that awareness to the front of your consciousness. Don’t get complacent—that’s what will get you into trouble.”

–Shane Hobel, founder, Mountain Scout Survival School

Level 2: Surviving a Day

You escaped the immediate threat, but as the minutes stretch into hours, your ordeal is just beginning. Choose your next moves wisely.

Coax Flame from a Spark

There’s no better heater, S.O.S. signal, or morale booster than a crackling fire. No lighter? Start one the old-fashioned way.

1. Gather

Sparks are tiny, fragile things, and they won’t last long without the right environment. Collect dry grass, frayed wood shavings, shredded birch bark, cattail fluff, or dried ferns, which all take a spark particularly well. Build them into a loose nest big enough to fill two cupped hands. Set it aside. Then, gather bundles of sticks of varying thicknesses—pencil-, thumb-, and wrist-size—and build a teepee with the smallest sticks on the interior and the largest on the outside. (Leave enough room between sticks for plentiful airflow, and leave an opening in the center of the teepee to insert tinder.)

2. Scrape

If you’ve got a magnesium or ferrocerium rod, scrape a dime-size pile of shavings into the center of your tinder bundle. If you don’t, go to the next step.

3. Spark

Kneel as close to the bundle as possible. Hold your ferro rod or flint palm-up in one hand, and brace that hand against your thigh. The end of the rod should touch the tinder. Scrape the back of the knife blade (the straight edge just behind the tip works best) down the rod in a firm, even stroke to throw sparks onto the tinder bundle. Repeat until the tinder catches.

4. Breathe

When the tinder’s smoldering, lift the bundle. Blow gently, careful not to extinguish the spark or send shavings airborne. If the ember fails to grow after a few exhales, throw more sparks.

5. Build

When you have a small flame, tuck the tinder into the teepee. Blow gently if it starts to fizzle. When the smallest sticks light, close the door of the teepee. Add bigger kindling as the fire grows.

Key Skill: Find Water in the Desert

1) Look for a wash. Dig at the outside of a curve in the waterway—it may yield subterranean water. If the soil’s not damp a foot deep, try elsewhere.

2) Walk downstream. You might find surface pools or wet spots (dig there).

3) Look for green. Vegetation is often a giveaway for the presence of a nearby spring.

4) Follow animal tracks. They may lead to water.

Shake Off Stress

After the adrenaline wears off, there’s just you, holding your life in your own hands.

Think of stress as a cloud. It inhibits decision-making in ways scientists haven’t quite figured out, but most agree that too much of it almost always breeds bad choices. Stress makes us act before we’ve considered all options. It wakens a chattery inner voice that explains away “missing” lakes or mountains—a phenomenon called “bending the map.” It tells us to keep going lest we be forced to admit that we’re lost.

So your best first move is to breathe, observe your surroundings, and do simple tasks (like making a snack) until the panic subsides. “Check your pulse,” suggests Robert Koester, the CEO of search-and-rescue research company dbS Productions and author of Lost Person Behavior. “If it’s in the normal range, 60 to 80 beats per minute, the adrenaline rush has died down.” Only then is it time to make a plan.

The good news? Research suggests that stress turns us all into risk managers. So while you might not make the best decisions, your psychology is firewalled against making those likely to kill you. Find that reassuring.

Game: Survive in the Alpine

It Happened to Me: Falling Through Thin Ice

In December 2013, Samantha Robbins fell into an icy lake near her family cabin in Cle Elum, Washington, and lapsed into hypothermia. As told to Stasia Callaghan

It was a clear, 21°F December morning, and I had just gotten a new camera, so I strapped my snowshoes on for a quick hike down to Kachess Lake to test it out. It was just over a mile, but the path was steep and filled with deep snow.

At the shore, I found a few stumps sticking out of the water. If I could climb onto one, I figured I’d get some cool shots. So I set down my pack and camera and stepped onto one stump that appeared wet from snowmelt, just to test it out. But what I thought was a sheen of water turned out to be a layer of ice, and I slipped, plunging into the lake. The ice-cold water ripped the breath from my lungs as my head submerged. I fought for the surface, then the shore.

I shed my wet jacket and shirt and burrowed into the dry coat in my pack. Still shuddering, I began the adrenaline-powered hike back up the trail. My ears were ringing and my pulse was racing so violently I could hear it thumping in my head. I slogged uphill for 20 minutes and was about halfway back when the adrenaline started to drain from my system. I sat down, sagging into a snowbank. My muscles refused to work. All I could do was lie there.

I could feel my heart rate dropping and breaths slowing. I wanted to sleep. After five minutes, I tried to move again and found my pants had begun to freeze to the ground. That scared another jolt of adrenaline out of me—enough to peel myself up and keep hiking. At the cabin, I immediately put on dry clothes and climbed under the covers. My brother took my temperature: 93.8°F—any colder, and I might not have been able to get up out of that snowbank at all.

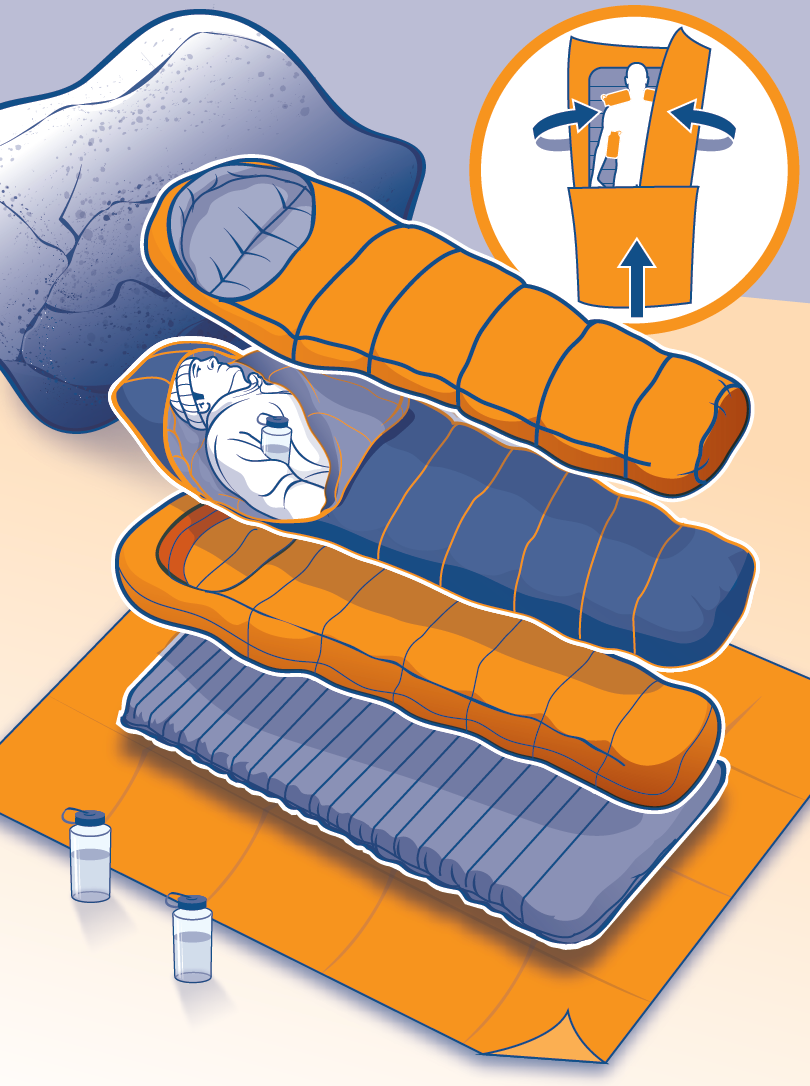

Key Skill: Make a Hypo-Wrap

Cold and wet? Body temperature can drop to 95°F in as little as 15 minutes. Here’s what to do for a severely hypothermic partner.

1. Replace wet layers with dry ones.

2. Lay down a tarp or tent fly, then a pad.

3. Stack three sleeping bags (if possible). Get your partner into the middle one.

4. Add hot water bottles (put them in socks).

5. Wrap up the tarp, burrito-style.

6. Get him or her to consume snacks and warm drinks.

Level 3: Long-Term Survival

Most search-and-rescue operations resolve within 24 hours, but some push both the clock and the human ability to endure. Play on to find your breaking point.

Get Unlost

Face it: You’re beyond “just a little turned around.” Try these strategies.

- Triangulate. Align the 0-degree mark on the compass with north on the map, then spin both together until your needle points north (adjust for declination). Match two landscape features to the map. Draw a bearing line from each landmark. Your location should be where they intersect.

- Backtrack. Retrace your steps to the last place you knew where you were. Do better next time: Compare your surroundings to the map every half hour and note waypoints like peaks, ridges, or lakes. On trail, mark off junctions and landmarks as you pass them.

- Sample routes. Can’t backtrack? Hike a short distance in several directions (take a waypoint so you can get back to your original position if you need to).

- Wait it out. No dice? Stay put if you expect a rescue.

Better plan: Don’t get lost in the first place. Take our Backcountry Navigation or Basic Map and Compass Skills online course from AIM Adventure U.

How I Survived

Three survivors share the stories of their ordeals—and what came after.

Frostbitten and Stranded

“Why don’t you just meet me down the hill? I think I’m going to ride down,” I told the dumbfounded National Guard medic. He had rappelled from a helicopter to save me. My body temperature, he’d just told me, was 86°F. Read the full story.

Mauled by a Mountain Lion

The animal sprang out of the brush in Whiting Ranch Wilderness Park in Southern California without warning, and the force tore me off my bike and off the trail I’d been riding. I fought, thrashing and punching as its jaws clamped down on the back of my neck, and then my face. I felt my left cheek tear away. Read the full story.

First, the Accident. Then, the Invisible Trauma.

I felt shaken for weeks. The accident affected each of us differently, and we mostly dealt with our trauma on our own. I blamed myself, especially at first. I knew it had been an accident, but I also knew that my friends wouldn’t have been injured if I hadn’t fallen. Read the full story.

Build Long-Term Shelter

You’re starting to realize you’re going to be here for a while. Here’s how to settle in for the long wait.

Scope your options. Find a spot close to water, under tree cover, and within walking distance of an open field or ridge for signaling. Avoid camping on game trails or in wind-exposed areas or cold sinks.

Erect a Shelter. With the door facing away from the wind, put up a tent or tarp, or build a lean-to or debris hut. For the latter (the most protective option), butt the end of a slender, 12-foot log against a rock, and prop up the other end about 3 feet off the ground using two planted Y-shaped sticks at a 90-degree angle to one another (rest the log where the two forks overlap). Next, lean adjacent wrist-size sticks against either side of the log at a 45-degree angle. Pile leaves or duff 3 to 4 feet thick against the ribs. (Gather all wood at least 200 feet from camp so if you get hurt or sick you’ll still have materials within easy reach.)

Add insulation. To protect your body from the cold ground, add at least a 12-inch layer of leaves to the floor of your shelter. Using a tarp? Pile snow or dry debris around the edges to seal out weather.

Don’t Stop Believing

Emotional resilience can be the difference between enduring a long-term survival challenge, and succumbing.

Leave optimism to the rubes; it’s not as helpful in a survival situation as you might think. According to Steven Southwick, a professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, the overly optimistic can be just as dangerous as the pessimistic: They tend to overestimate their abilities and underestimate hazards.

Resilience comes from realistic optimism: acknowledging the negatives, then forcing yourself to look at the positives. According to Southwick, survivors of long-term trauma tend to be able to set aside their fear: They see it as a helpful guide rather than its own emergency.

To get to that point, Southwick recommends acknowledging your fear, then using positive self-talk to keep up your morale (and temper your stress response). “Tell yourself, ‘I’m a lot stronger than I think. I have a reservoir of resilience and I’m going to call on that,’” Southwick says. “Stay positive. Imagine that you’re going to make it out.” Do that and you just might.

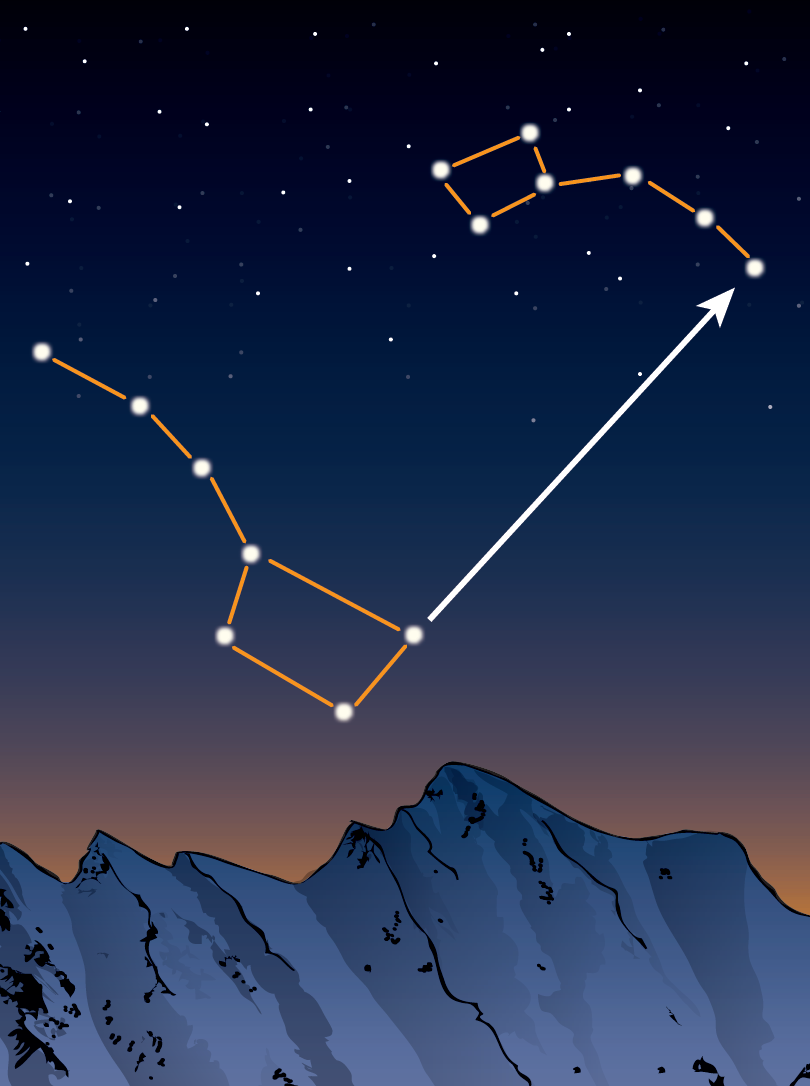

Pop Quiz: What Star Is This?

If you answered the North Star, pat yourself on the back.

Tip: If you can’t see the Big Dipper, find your direction using the moon. Draw a line through the two points of a crescent. You’ll find south where that line intersects the horizon.

The Final Level

These tips are a great start. Now take your lifesaving know-how to the next level with our online class, Outdoor Survival 101.

Your Instructor: Shane Hobel, founder of Mountain Scout Survival School

Course topics: Building shelter, making fire, finding and filtering water, foraging, crisis management, and more. Use the code BPMAG at checkout for a 20 percent discount.