Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

A few weeks ago, I was at home, sitting in a remote work meeting, when I got a text from my mom.

“I just got a message and I think it’s probably a scam, but it’s about an emergency rescue beacon going off and I’m the contact person,” she wrote. “I doubt this is real, but please let me know you’re OK.”

I couldn’t blame her for thinking it was a scam—I was safely at home, and definitely hadn’t sent out an emergency signal. I brushed it off, until a few minutes later when I got the same voice message from someone at the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center, quickly followed by one from the Colorado Search and Rescue Association (CSAR) asking if I was in distress. I live in Washington, but I used to live in Colorado. If this was a scam, it was an elaborate one. As soon as my meeting ended, I called back.

The personal locator beacon (PLB) in question has been sitting in my storage unit, in a box of old hiking gear, for the past two years. When I got the device, I registered it with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), inputting my mom’s phone number for emergencies, and my own as the owner of the device.

I told the rescue coordinator that I was, in fact, safe and sound. Since I’d be unable to access the activated device and it would be difficult for responders to locate it among my stored items, he told me that we could just let the battery run out.

When CSAR called me, Colorado was enduring a brutal summer heat wave. The SAR coordinator I spoke with hypothesized that soaring temps in my storage unit were the likely culprit for activating my beacon, but no one else I spoke to was able to corroborate this theory. ACR units like mine are designed to withstand temperatures up to 160°F. On the day my beacon activated, the peak temp was around 99°F; even if it got hotter inside my unit, it’s unlikely that the device was exposed to temps even approaching this upper limit. More likely, a box fell and compressed the unit, or maybe even a critter somehow set it off. It’ll remain a mystery until I go retrieve the device from storage.

I’ve covered dozens of rescue stories for Backpacker, and I’m well aware of the benefits of devices like PLBs and satellite communicators. But I’d never considered the impact of non-emergency activations. If my unattended beacon could trigger an emergency response from inside a storage unit, I wondered how often accidental activations send SAR teams on wild goose chases, and if this causes resources to be diverted from people who are actually in need of help.

As it turns out, false alarms aren’t uncommon when it comes to SOS devices. I spoke to Bruce Beckmann, a state coordinator for CSAR, to learn more. At the time of our call in early August, CSAR was monitoring two suspected accidental activations. Beckmann told me he was aware of 12 false alarms across the state of Colorado so far in 2024.

How PLBs work

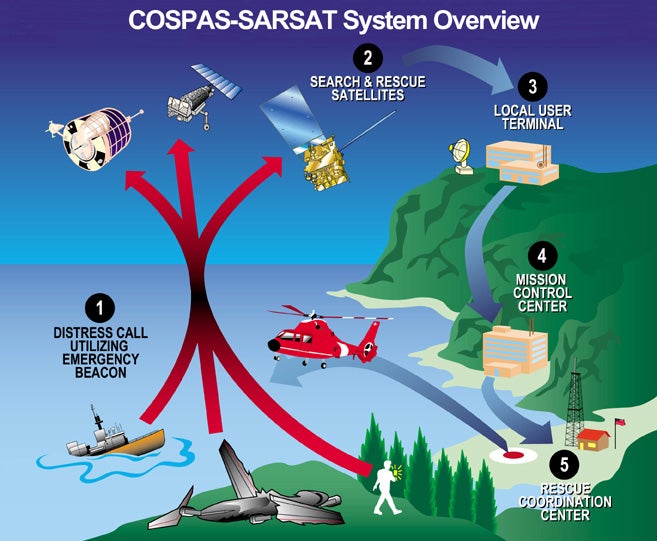

Personal locator beacons, like the ACR ResQLink or McMurdo FastFind, rely on a network of satellites to inform SAR teams of a victim’s location in the event of a distress signal. Unlike many satellite messaging devices, like the popular Garmin inReach, PLBs don’t have the capacity for two-way communication, and they don’t require a subscription, so they’re always ready for deployment in an emergency.

When a hiker activates the SOS function on their PLB, the device pings a satellite, which alerts a rescue coordination center such as the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (AFRCC) in Florida—the same one that called me. The AFRCC then alerts state or regional SAR authorities, giving them coordinates for the alert and any information they can access about the device’s registration and emergency contacts.

The location accuracy can vary widely, and sometimes SAR teams have to wait for satellites to make additional passes before they have enough information to initiate a response. Additional satellite data can help rescue coordinators determine whether a device is moving, and the locations often give insight into whether an SOS is real or inadvertent.

Common causes of accidental activations

Many PLBs require multiple steps to initiate a signal, like extending an antenna and holding down a button. These steps are intended to mitigate the risk of inadvertent distress calls, but accidents still happen. Both Beckmann and Mikele D’Arcangelo, VP of global marketing, product management, and customer support at ACR, told me that my case was the first they’d heard of a device activating from inside a storage unit. According to D’Arcangelo, the vast majority of false alarms are the result of human error.

According to Beckmann, any number of factors can cause a PLB to send a false signal. Sometimes, kids playing with their parents’ device accidentally hit the SOS button. Jostling in a pack or pocket can sometimes do the trick. Often, activations occur after someone has thrown the device away.

“We’ve had a couple of landfills where in moving and pushing dirt or trash around, it’s activated,” Beckmann said. “What are the chances of straightening up an antenna and hitting that button for a couple of seconds?”

In one surreal case, Beckmann said that a satellite signal led authorities to a zoo, where the activated device was buried in an 8-foot-tall pile of elephant excrement. It turned out the device had been reported lost a few years prior. No one was able to answer how it ended up in the poop.

Beckmann theorizes that PLBs that don’t allow for two-way communication will soon become obsolete, especially as satellite messaging becomes widely available on smartphones. While this will reduce the risks of false alarms, it likely won’t solve the problem altogether. Satellite messaging devices, which allow users to send pre-programmed or personalized notes to loved ones and authorities, come with their own potential complications. In one case, Beckmann witnessed an entire backcountry rescue operation that resulted because a user failed to sync his device with his computer after updating his pre-programmed messages.

With the click of a button, the man thought he was repeatedly telling his wife “I love you.” In reality, the device had sent multiple messages saying, “need help, send help.” A handful of rescuers and a military Black Hawk helicopter responded in the middle of the night, only to discover the man was fine.

With accurate location information, some cases are clearly false alarms (like when coordinators can see that a device is at a recycling center).

“If they’re in a car going through three different counties, it’s not very likely that they’re in distress,” Beckmann said.

In other cases, they’re unable to get accurate coordinates and must monitor the situation. Whether or not to send SAR teams ends up being a judgment call for rescue coordinators and the local sheriff. Responding to false alarms puts unnecessary risk on rescue personnel and diverts resources from true emergencies.

What to do if you accidentally activate your beacon

If you are aware of an accidental activation, you can get in touch with rescue coordinators before they deploy emergency resources. For PLBs, NOAA suggests calling the Air Force at the following number: 1-800-851-3051. A coordinator will flag your signal as a false alarm, and instruct you on deactivating the device.

Proper storage and disposal

Properly storing and disposing of PLBs can help mitigate the risks of accidental activations. As I learned, a non-climate-controlled storage unit isn’t the best place to keep a PLB. Instead, store your device in your house, or somewhere where temperatures won’t fluctuate into extremes.

Federal regulations require that satellite beacons be registered with NOAA, which is crucial both for fast response in case of an emergency and to mitigate the effects of false alarms. New devices come with registration instructions, or you can follow them on NOAA’s website. You should renew your registration every two years; failure to properly register a device can result in fines from the Federal Communications Commission.

When your device reaches the end of its life, decommission it by dismantling the device with a screwdriver, removing the batteries, and properly recycling them. Never chuck the entire device in the garbage—that’s a recipe for a false activation. Update your registration to reflect that the device is out of commission. If you ever lose your PLB, contact NOAA at the following number: 1-888-212-7283. They’ll ensure that your registration is properly updated.

PLBs save lives

To ensure proper function of a personal locator beacon, Beckmann recommends carrying it any time you venture into the backcountry—no matter how far you’re going.

“I wish I had a dollar for every time somebody said, ‘but I’m only going to the lake. I’m only gonna go a half mile,’” he said. “Once you’re immobile, you need help.”

Beckmann also recommends keeping your beacon within reach at all times, rather than stuffed into the bottom of a pack. That way, you’ll be able to easily access it in case of an emergency. Keeping your device handy may also reduce the risks of it accidentally going off in your pack.

From 2024