Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The Victim Marcia Rasmussen, 53, plummeted into the ice-choked waters of Franklin Creek while running in Sequoia National Park on June 14, 2011.

The raging, snowmelt-fueled current swept me downstream, and I grasped at the featureless white walls slipping past, desperate for hand- or footholds—anything that would keep the waist-deep creek from pushing me over the 10-foot waterfall downstream. By the time my chilled fingers caught a protruding branch, the current had swept me 60 feet down a tunnel of ice. I gripped my pathetic lifeline, a pencil-size twig, with all my strength and crawled out of the rushing water into a cave barely large enough to keep my curled, 5’4” frame out of the raging stream. I felt like a captive, but lucky to be alive.

At 11:15 a.m., two hours earlier, I’d set out on a high-altitude training run in California’s Sequoia National Park in sunny, 70°F temps. I was prepping for an ultramarathon and had come to the park for a scenic workout, and to see how close I could get to the 10,500-foot passes atop the Great Western Divide. The Franklin Pass/Farewell Gap trailhead at 7,800 feet was snowfree, and I climbed five miles and 1,000 vertical feet before the trail’s surface became snow-covered and treacherous enough that I had to turn around.

On my outbound run, I’d noted the potential instability of the five-foot-deep snow bridge over Franklin Creek, but I’d prodded the surface with a hefty stick, and I’d knelt to examine it. There were no visible signs of weakness, and the surface was rock hard—I guessed it could support a truck. Though I didn’t have skis or snowshoes to distribute my weight, I crossed without incident.

Conditions past the creek stayed cool for the duration of my run, but I expected the lower-elevation snow to soften as the day warmed. So when I approached the snow bridge again on my return trip, I examined it thoroughly.

(…continued on next page)

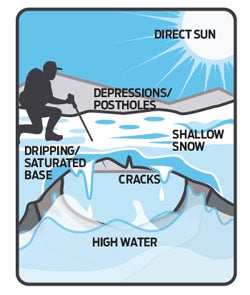

I poked at the surface again and knelt to scan the snow for cracks or depressions— telltale danger signs. From my vantage, however, I couldn’t see the bridge’s base, which was losing strength as the creek swelled with meltwater that splashed the icy structure from below. Had I used a probe or pole to test deeper than the frozen surface, or had I been able to see its base, I might have noted that it had weakened.

I was two miles from the trailhead when the bridge collapsed beneath my feet. Plunging into the fast-moving, 40°F water, I struggled against the powerful current, trying to stay afloat and slow my passage through the tunnel. Thankfully, I was able to crawl into my tiny alcove before going over the falls or being pinned underwater. But the stream lapped my toes, and my running clothes offered little insulation. I craned my neck up- and downstream looking for a way out, but the tunnel extended as far as I could see. In an attempt to calm myself and think clearly, I lay back and stared at the cave’s ceiling. Sunlit teals and blues shone through, the palest spots hinting at the thinnest layers of ice. Wise or not, my only choice was to punch through the roof of this icy tomb. I scratched at the ice with my bare fingers, which soon numbed with cold. It was like defrosting a freezer barehanded, but as I clawed at the ceiling, it thinned and brightened. After two hours of digging, I’d tunneled through several feet of ice and snow, finally breaking the surface with a finger-size hole.

After another hour, I’d stretched the window’s width to six inches, but the tunnel was still too narrow to crawl through. Digging had helped keep me from succumbing to the cold, but I was exhausted, struggling to stay conscious, and getting hypothermic—physically incapable of further widening it. Knowing I had to draw attention to myself, I thrust my daypack through the vent and onto the surface, hoping it would be a beacon to passersby. The last-ditch tactic worked! Just moments later, my legs frozen and my muscles seizing as I looked desperately through the hole, a pair of eyes popped into my field of vision and gazed back at me. A hiker had come to investigate my blue pack, and within minutes he and his companions freed me from the icy vault. Ten days later, the snowbridge was gone, but my frostbite scars remain.

Key Skill:Cross a snow bridge

Assess the consequences of falling through, especially over waterways. Look for indications of weakening snow (see right) and change your vantage so you can scrutinize a bridge’s sides and base. If possible, cross where bridges are supported from beneath by rocks or fallen trees, or in low areas where a fall won’t hurt or trap you. Time your crossing for the morning, when the bridge will be strongest, and the water volume flowing beneath it will be lower.

Skill:Signal for Help

3 key ways to attract rescuers

- Make noise. Use a whistle (carry it on your person) and blow three consecutive blasts every several minutes. Yell if you can hear rescuers calling for you.

- Increase visibility. Place bright items where passersby, search parties, and rescue helicopters will see them. Reflect sunlight or shine your headlamp.

- Point the way. If you move, leave signs or create marks indicating your travel direction. For more signaling gear and techniques, visit backpacker.com/signals.

Stop Sliding Cutting steps can help you cross icy slicks or hard surface snow without slipping. Learn how at backpacker.com/cutsteps.

–> Watch this video of the view under Franklin Creek’s Snow Bridge shot by one of Rassmusen’s rescuers, Stefan Barycki.