Out Alive: Mauled by a Grizzly Bear

'Grizzly bear cubs typically stay with their mothers for two to three years. Photo by Tom and Pat Leeson'

The two bear cubs bolted past me, one on either side. Everyone knows what follows cubs, and when I looked up from where I was sitting against a small pine, I saw the golden brown hump of a grizzly’s shoulders. She stepped clear of the underbrush 15 yards away. When her eyes fastened on me, I saw the hair on her hump rise as she laid her ears back.

I didn’t get a chance to wonder how she had gotten so close so quietly—or anything else. She charged as soon as we made eye contact. I didn’t even have time to get the bear spray out of my belt holster. The sow was on me in seconds.

I put my forearm up to block her and she bit that first, sinking in her teeth. Then she clamped me across the temples, ear to ear. I heard bone crunch and thought, I’m done.

This wasn’t my first time in bear country. Each fall for the last 12 years my wife Diane and I had traveled from our home in Pennsylvania to backpack into this remote Montana wilderness and others like it. We were always well prepared: On this trip, we carried a beefy med kit; noted the make, model, and license plate of our rental car in case we needed to give it to rescuers; left detailed plans with friends; and brought along a satellite phone, which we went so far as to test for reception.

That August day, we were in a meadow, less than a mile from camp. I was using a cow elk call, staying low and hidden, hoping to call in a bull. We had often seen tracks and scat from mountain lion, wolf, and black and grizzly bears, but had never encountered the animals themselves. We were aware of dangerous wildlife, but, owing to our preparations, never felt nervous.

But you can’t prepare for a mauling. When the bear was on top of me, I could hear Diane screaming. She was about 20 yards from me when the attack started, slightly screened by brush. She had moved away from her daypack, with its bear spray holster, to see what was happening, and then screamed at the sight. Maybe her loud yelling helped, because the bear stopped biting me and backed off.

“Bear spray! Bear spray!” I shouted, bleary-eyed and dazed.

The noise seemed to agitate the bear; she bounded back at me. I tried to defend myself by kicking her in the nose. But she was too powerful; the blows glanced off. I thought I should “play dead” and that lying still might be the best thing to do, but that’s easier thought than done. I saw the bear open her mouth and instinctively I tried to duck and fend her off. The bear grabbed me across the skull again, her jaws spanning my head front to back, scraping and gnawing. Diane screamed again and the grizzly was off me and gone.

The entire encounter lasted only two or three minutes. The bear melted back into the underbrush, but we weren’t sure she had left the area. We couldn’t wait long. Diane raced to my side. I looked up to see her white and worried face.

Then Diane went into action, retrieving a packet of blood-clotting agent from her daypack (she’d packed it in our first-aid kit just in case). She gently pulled the sections of my hanging scalp as much back into place as she could. She laid the clotting agent against my worst wounds, applying pressure. Then she wrapped my head with gauze and secured it by knotting her shirt.

By then I was sitting up. Diane asked me if I could walk, and I said yes. We were both keen to get away from the attack area and back to our camp. When we got there, Diane got me settled at the tent, and used the satellite phone to call for help. Rescuers told her that every step we could get down the trail would make evacuation that much easier.

We stripped our packs of nonessential items and abandoned camp. The going wasn’t hard at first, but, soon, the shock of what had happened started setting in. The pain intensified, especially in my forearm, where the bear had clamped down her jaws. Diane tied our two bandanas together to make a sling for my arm.

About 3 miles from the trailhead, I looked up and saw the incoming rescue team. We stopped and they checked my condition. I was doing well enough that the rescuers didn’t need to carry me, but I did accept a ride on a mule one of them had brought in. From the trailhead, an ambulance carried me to the nearest hospital 25 miles away.

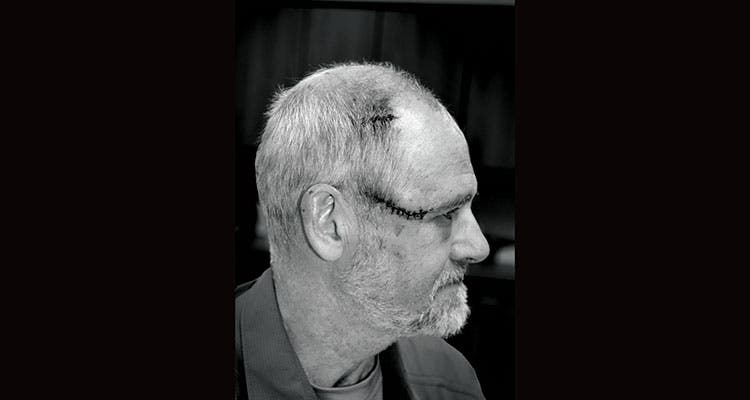

The staff there tallied my wounds. I had been raked by her claws and one gash in my neck was dangerously close to a major artery. As for my head injuries, the bear had cracked my orbital bone (that was the crunching noise I’d heard). My arm had puncture wounds from the grizzly’s bite, and my scalp and arm wounds took 35 stitches and nine staples to repair. I was given rabies shots.

Today, I have fully recovered. Everything has healed with hardly a scar. A year after the incident we went back to the same meadow where the attack took place because I felt I had unfinished business there. To return was another kind of healing.

Since then we’ve camped in the same area and visited the site of the attack each year on our annual wilderness camping trip and have not seen another grizzly. We enjoy wildlife and I look forward to seeing another bear some day. Just not that close.

Bear Country Safety

1. Ready, aim. . .

We’re going to assume you have bear spray here (because you should). As soon as you see a bear, remove the safety clip and be prepared to fire. Spray only if the bear becomes aggressive and is closer than 60 feet away. Aim slightly downward using a side-to-side motion to create a cloud barrier between you and bear.

2. Vocalize

Sing or speak in a calm and monotone voice. You’re not trying to scare it away; you just want to show you are human and not a prey animal.

3. Back away

The trick here is to walk slowly, not run, even though every fiber of you wants to sprint. Mother grizzlies are extremely protective, so they might pop their jaw, swat at the ground, or bluff charge at you if they feel you are too close. Keep calm and retreat slowly.

4. Play dead

If the bear attacks, fall to the ground, lie on your stomach, and cover the back of your head and neck with your hands. Wait on the ground until you are sure the bear is gone (even if it takes 30 minutes or more). Caveat: If the bear starts to feed, fight for your life, going for eyes, nose, and ears.

5. Take a detour

Give bears a wide berth and avoid any behavior that might be interpreted as aggressive. –Carolyn Webber