Out Alive: Lost in the Desert

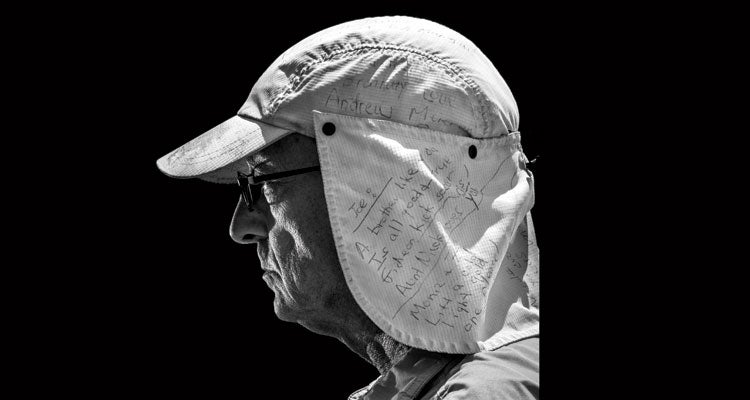

'Rosenthal wrote goodbye notes and poems to his friends and family on his sun hat. (Michael Darter)'

I could see the lights of civilization 10 miles in the distance, promising salvation. But i was too thirsty and tired and sun-baked to answer the call. i could barely move. No one knew where i was. The lights glimmered like a cruel mirage.

I had set out solo four days earlier, on Friday morning, for a celebratory hike up to 4,900-foot Warren View, a peak in Joshua Tree National Park—my longstanding ritual after closing big real estate deals. I knew it was only an hour and a half—less than 3 miles—to the top, so I didn’t bother to top off the half-quart of water left in my hydration pack or bring maps. I grabbed my daypack, which had most of the 10 essentials, but left my jacket and layers in the car, and soaked in the cleansing 90°F September sun as I climbed.

To the southwest, 10,834-foot San Jacinto peak dominated the horizon as I ate lunch at Warren View, and I scanned the contours of the San Andreas Fault to absorb wide desert vistas and the feeling of being on top of my game. But then, when I turned to head back, something wasn’t right.

I couldn’t make out the little-used, rocky trail. I had passed a sign on my way up that read West Trail, but when I descended I missed it. I couldn’t clearly recall the landmarks I’d used to navigate back before. Everywhere I looked appeared unfamiliar. I scurried the quarter-mile between Warren View and Warren Peak and finally spotted what looked like a terraced ravine that ran toward where I thought the trailhead was. I went for it, thinking it would intersect the main trail.

I wove downhill between cacti, leaning hard on my hiking pole on the 40-degree slope. Three times I had to jump down rock faces, each time realizing the climb back up would be impossible. After the last 15-foot downclimb I admitted that I was following a dry creekbed—no trail in sight—and I had no clue where I was going.

But the answer had to be downhill. I stumbled along for another half mile, when suddenly, miraculously, I stepped out onto a real trail. It’s going downhill, I thought. Out of the mountains! I followed it for three hours, charging ahead in pursuit of fuchsia and yellow prickly pear blooms that I mistook for hikers’ shirts. Each time I turned a corner my hope was swallowed by the vastness of the folded terrain. I could see the desert changing form ahead, flattening out into a sea of dust and scrub brush shimmering in waves of heat. I knew I’d transitioned from the Mojave into the Colorado Desert—a hotter, more hostile land.

I turned around and worked my way off-trail to a sandy depression where, six hours after I started my dayhike, I hunkered down for the night. I could see airplane lights blinking rhythmically overhead and I signaled to them by flashing my headlamp against my emergency blanket, but it was no use. No one even knew I was lost; I wasn’t supposed to check in with my wife until Monday (I was on a dayhike, but planned to be away longer), and that was two days away.

Dawn prodded me awake and I tried eating some dates I had in my pack. I chewed and chewed, but without saliva, they stuck to the roof of my mouth like peanut butter, gagging me. I was already dehydrated and I’d finished my water the afternoon before. I tried sucking on pebbles to create saliva, but nothing happened. I tried to drink my urine, but spat it out.

I retraced my route back down to the trail, and stood at the mouth of a red-hued canyon, trying to discern where to go. Thirty or more trails spun into the desert. I picked a path that looked like it was made by humans. I knew I could backtrack and try another trail if this one led nowhere, but wasn’t sure I could stand much trial-and-error—I was thirsty, tired, and depleted. (I later learned I’d hiked 18 miles.)

The sun beat down, drying out my nose and mouth until they felt like rubber. Exhausted and panting, I stumbled to a lone evergreen set on a tall hill and crawled under its branches for relief and shade. I fell asleep immediately. Every hour or so the sun shifted enough to burn my legs. I crawled back into the safety of the shade and collapsed again.

When the heat of the day relented, I knew I had to find water. I’d been without it for more than 24 hours, and knew I wouldn’t make it much longer. I thought I could squeeze water from a yucca plant, and I pried at its pistachio-colored flesh with my knife to no avail. I couldn’t get it to produce a single drop.

As the sun set, I found myself hundreds of feet higher than the lone pine tree, and the air cooled fast. I tried to start a fire with my survival matches, but my hands were shaky and I couldn’t find enough fuel. No combination of flame and tinder could keep my pile of twigs lit, so I pulled a roll of toilet paper (I didn’t think to try it as tinder) from my pack and wrapped it around my arms and legs to substitute for the warm layers I’d left at the trailhead.

When the first shiver hit me I felt truly afraid. I didn’t think I was strong enough to fight hypothermia. I’d survived a heart attack several years before, and vowed to never get worked up again. It took all I had to calm myself through the night, and I spent hours watching Orion and Vega spin overhead.

The next morning brought me two goals: stay in the shade, and find a warmer place to sleep. I’d given up on self-rescue. I rose, weakly, and moved downhill. I attacked the yucca fronds again to no avail. (I’d later learn that yucca don’t produce drinkable water; neither do most cacti.) Within a mile I was too hot to carry on—each time I sat down I struggled to get up. I crawled under a rock and repeated my dance with the midday sun. Sleep, burn, crawl. Sleep, burn, crawl. I awoke once to notice a small canyon 50 yards away. I stumbled into it and collapsed in the shade, only moving when the sliver of sun at the bottom touched my skin.

Each time I moved I felt my strength leave me. I thought about my wife and 20-year-old daughter at home and how I missed them, and I scribbled messages to each of them on my hat in case someone found my body. I said the Shema Yisrael—a Jewish end-of-life prayer—and prepared my mind for the possibility that I might die soon.

When the stars faded above my canyon, I was too weak to move far. All I could do was crawl after the shade as it eluded me along the vertical wall. A fly buzzed around my head. It was the only living thing I saw, but it brought me comfort to know I wasn’t alone.

Tuesday I awoke to the sight of Orion in the morning sky, and I felt strong enough to try signaling rescuers again. I limped 40 yards to a clump of tall, dead grass against the canyon wall and lit it. I struggled back to the shade and watched it emit smoke for 15 minutes before the fuel was gone. I sat and waited for what felt like ages, but nothing happened. I was still all alone. I crawled back to my shade and fitfully slept. I was out of firestarters. I was out of options. I was spent.

When I awoke on Wednesday I couldn’t move at all. I lay on a rock and stared at the sky, praying for rain. Miraculously, it came.

Intermittent showers doused me with cool drops and soothed my parched mouth. I dozed between showers, thankful for a respite from the heat and sun. I didn’t have the energy to try to gather rain. I didn’t even try. All I could do was lay still, mouth open, at nature’s mercy.

The next morning I didn’t wake up with the light. My body resisted attempts to move. My eyelids felt glued shut.

It all ended suddenly when I heard the metallic whirring of a helicopter above my canyon, and a man’s voice ask, “Hey, are you that Rosenthal that’s out here?” He carried me out of there.

[Key Skill]

Signaling

Properly alerting rescuers is critical. Here, John Gookin, a SAR veteran and NOLS curriculum manager, explains the best methods to get found.

Short range

(200 yards)

Headlamps and whistles are best applied once search and rescue is close and you can either see people or hear them nearby.

Medium range

(up to 15 miles)

Use a mirror or any shiny surface (watch, spoon, or emergency blanket folded into hand-held size, etc.). Hold it with one hand, and outstretch the other in front of you, opening your fingers in a V shape. With your target between the V, flash back and forth.

Long range

(up to 25 miles)

Prepare one or more signal fires. Get instructions at backpacker.com/fire