Out Alive: Caught by a Strainer

'The Victim Judy Joiner, 59, fights for her life on August 20, 2011, in Alaska’s Gates of the Arctic National Park. (Illustration by Johnny Dombrowski)'

The VictimJudy Joiner, 59, fights for her life on August 20, 2011, in Alaska’s Gates of the Arctic National Park.

I only lost control for an instant, but the fast-moving water swung my boat sideways and within seconds, the current glued me to a submerged barrier of downed trees. I was living every kayaker’s nightmare: a bramble of branches or a fallen tree (aka a strainer) acts like a sieve, trapping a boat as building water pressure pushes it underwater—sometimes with the boater still inside. Within seconds, most of my 13-foot inflatable kayak—and half my body—was immersed in the 55°F river. Would the current trap me against the wall of 2-inch-thick branches? My mind reeled. Am I going to die?

About a week earlier, my husband Ralph and I joined two friends, Barb and Henry, for a 10-day trip of a lifetime along a remote stretch of the Koyukuk River, deep in Alaska’s Brooks Range. A ranger at Gates of the Arctic National Park warned us the river was running high and fast, but we weren’t fazed. We had chosen the Koyukuk because of its “family friendly” reputation. Though we expected to encounter swiftwater on our 113-mile route, the river’s average drop is fewer than 8 feet per mile—nothing compared to 30- to 50-foot-per-mile whitewater runs—so we expected plenty of lazy-river-style paddling.

On day one, we realized we’d underestimated the wet summer’s impact on the current. Within hours of setting out, Barb and Henry’s canoe capsized and they lost both their paddles. (Luckily, they had one spare and we were able to jury-rig a second out of driftwood.) Their scary swim was a wake-up call for all of us; we grew anxious about unanticipated rapids, the fast-moving flow, and our route’s remoteness. But over the next week, we navigated the river’s upper reaches conservatively, with few incidents.

On day eight my luck changed. I was eyeing two paths around a small island and veered toward one with the hidden strainer. As I realized my mistake, the river sucked me toward the blockage. Within seconds, I broadsided it. I thought my limbs would get stuck in the loosely spaced branches if I climbed atop the strainer, so instead of trying that standard escape tactic, I grabbed a bough overhead and hoped that I could pull my boat from the tangle. I leaned hard to the kayak’s high side, trying to keep the upstream edge from getting pushed under, but I was no match for the force of the current. Within seconds, my legs were almost completely submerged.

Downstream, Ralph was able to beach his boat and run back along the shoreline to help me. Neither of us had swiftwater rescue training, so we’d never tried best-practice techniques like rope rescues. Eventually, Ralph opted to take a huge risk: enter the water himself. He decided the waist-deep, 8-mph current was slow and shallow enough for him to wade out and help.

Ralph fought his way toward me through the icy-cold water. (We both would have been much safer if we’d had our entire group to help with a rope-assisted rescue.) When he was within reach, I grabbed his hand and stepped into the river. I knew that one false move might put us both underwater, trapped against the bushes. But I fought the current, and reached shore safely. Ralph freed the boat before a hypothermic chill set in. Later, as we regrouped and warmed up next to a campfire, I was finally able to relax. Our final day would be short, and we’d pass through a broad, slow valley en route to the pull-out. Good thing: I’d had plenty of excitement for one trip.

Lifesaving Skill Escape a strainer

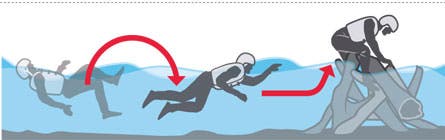

If you can’t avoid an obstacle, fight to climb on top of it as your boat hits. If there’s no one nearby to assist with a rescue, get off the strainer as soon as possible; dismount on the downstream side and get to shore. In the water heading toward a strainer? At the last second, switch from a foot-first to a headfirst position and swim hard, trying to launch yourself atop the tree to escape the current (see above). Don’t let your body swing parallel to the trunk, or allow your boat to pin you.

Never Forget

Groups are better for rescues and can more effectively scout safe passage, so keep boaters together. Individuals should each carry a throw bag, whistle, and river knife. Split critical group gear—such as rescue supplies, signaling devices, fire-starting materials, bear spray, medications, and first-aid kits—among different boats.