Out Alive: Broken Leg, Lost, and Alone

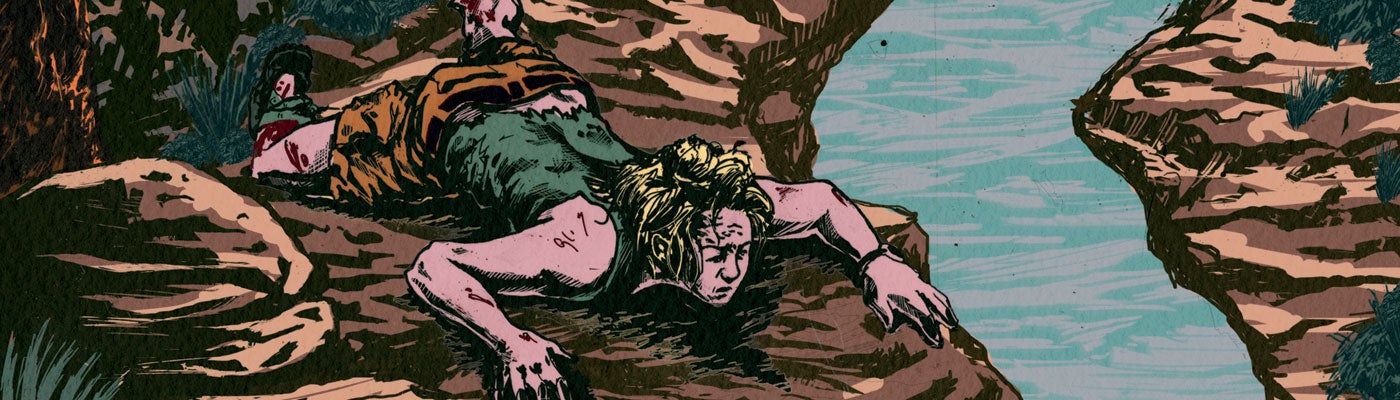

'Illustration by Justin Oon'

When I came to after I fell off the 50-foot cliff, I looked at my broken and bloody legs and realized I was in big trouble. I was lucky to be alive, but I was alone, without supplies, and no one knew where I was.

I had set out with my boyfriend the previous day to sneak in an overnight while the late-summer Oregon weather was at its finest. Our first choice for a campsite on Mt. Defiance was crowded, so we redirected to nearby Bear Lake, a smaller, less popular location with only one established site. But when we reached the lake we were underwhelmed. So we decided to leave our packs on the trail, split up, and search out a prettier, more secluded spot. Of course it wasn’t smart to leave my pack—and map, compass, headlamp, water bottle, everything—behind, but who hasn’t done something like it before?

Almost as soon as I left the trail, I got turned around in the thick forest at dusk. I should’ve called out to my boyfriend, but I didn’t believe I could really be lost. Instead, I walked to a high vantage point to reorient myself.

As the last of the light faded, I beat a path back toward the trail. I was scanning for our packs when I stepped right off of the ledge and fell 50 feet into a narrow canyon. I heard a snapping sound as I landed legs-first on a pile of rocks, and in the brief moment before I passed out from the pain, I remember one thing: bewilderment.

The next day, the agony was unimaginable. My left leg was broken at the tibia and I could see the bone bulging against the skin. My right leg was covered in sticky, drying blood from a 5-inch-long laceration that needed immediate cleaning. I felt for—and found—a pulse below the break in my left leg. I was relieved since I didn’t have splinting supplies close at hand, though splinting would have reduced pain and increased mobility.

Instead, I crab-walked 150 feet to the stream in the bottom of the canyon, where I cleaned my wounds with icy snowmelt and drank the unfiltered water. I was lucky it didn’t make me sick or infect my open cut, but my wound was filthy, so I took a chance.

I decided to crawl downstream and find help in the Columbia River Gorge, 8 miles northeast. While following water downstream can lead to civilization, staying put would have been smarter—but I didn’t realize my boyfriend would have gone for help. By pulling myself deeper into the canyon, I was moving out of earshot of the calls of rescuers. I just couldn’t calm my mind enough to wait.

As I went, I munched on salmonberries and huckleberries. I figured I was unlikely to starve, but eating gave me a mental boost. I avoided white berries since most of them aren’t safe, and looked for aggregate-style berries such as blackberries and raspberries. I tried to eat a large, brown slug, but it suctioned to my tongue and I coughed it out. I also tried sucking the soupy guts from a caterpillar that left a metallic taste on my lips. I knew to avoid bright colors and hairy bodies, which can indicate the bug is poisonous.

Darkness fell fast in the canyon, and I piled moss over my body to stay warm when temperatures dropped to 40°F. I used pieces of my clothing to keep my laceration covered and clean from debris. Still no one came.

On the third morning, I woke up to the sound of a helicopter. I heard it pass overhead and enthusiastically waved a sock in the air to attract attention. Rescuers reached me by early afternoon, and I recouped in the hospital for a week. I didn’t once complain about the food.

Never Forget Get Rescued

Stay put when someone knows your itinerary and will call for help if you’re late; you have adequate supplies; you’re near a well-used trail; you have an immobilizing injury.

Make tracks when no one knows where you are; you’re in immediate danger; your position isn’t visible to others; you don’t have the right gear to wait.

Key Skill: Improvise a Backcountry Splint

(1) Check for a pulse below the break. Reset the bone if you can’t find one (hold the bone on the far side of the break and pull it away from the break until you feel it align properly). (2) Use a sleeping pad—tent poles (shown), sticks, or pack stays work in a pinch—to immobilize a broken leg if you don’t have a SAM splint. (3) Fix the splint so it covers the joints above and below the break (over ankle and knee for tibia fracture, for example). (4) To maintain circulation, keep a slight bend in the knee by stuffing the space behind it with extra layers or leaves. (5) Use cord, pack straps, or clothing to fasten the splint on both sides of the break—don’t tie directly over it. (6) Inflate the sleeping pad and check the victim’s toes and foot for pulse and sensation. The splint should be snug, but it shouldn’t restrict circulation.

Cut bad? Learn how to clean deep wounds.