Heros: Becca Stubbs, 21

'Becca Stubbs (Photo by: Ben Fullerton)'

Becca Stubbs (Photo by: Ben Fullerton)

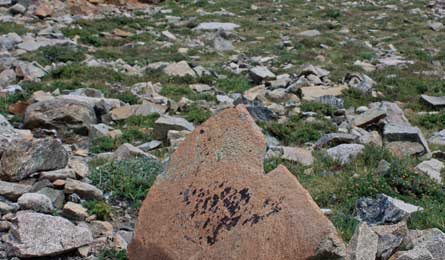

Doghouse-size rock (Courtesy Photo)

Becca Stubbs Severed Sacrum (Courtesy Photo)

Deep gash (Courtesy Photo)

Level platform (Photo Courtesy of Rocky Mountain National Park)

Becca Stubbs (Courtesy Photo)

Becca Stubbs and four partners strapped on their snowshoes at 2 a.m. on a calm January morning at Long’s Peak trailhead in Rocky Mountain National Park. They climbed 3.5 miles by headlamp to Chasm Junction, 1,100-feet above treeline. There they cached their snowshoes, banged a left, and “started getting pretty stoked” to be nearing their objective: the Iron Gates route, a class 2/3 scramble on 13,911-foot Mt. Meeker. Recent stiff winds had blown most of the snow from the route, exposing rocks leading to the summit.

“The sun was coming up, and there wasn’t one cloud,” she says. “It was a stunning day to be outside.”

Thirty minutes later, above Peacock Lake, Stubbs stumbled and started sliding down a 45-degree snow slope. “I tried to self-arrest, but the snow was so hard that I lost my axe,” she says. She struggled in vain to dig her elbows into the sidewalk-tough crust. About 50 feet later, her left leg hit a rock, and she flipped from belly to back. Then things went from bad to horrifying. She began skidding, almost like a skipping-stone, quickly covering another 120 feet. “I was sliding at 30 miles per hour,” she estimates, when her body slammed into a doghouse-size rock, in a field of jagged boulders. “The collision severed my sacrum from the rest of my spine,” she says. “I could feel the impact reverberating through my body, and I began to hyperventilate. Then I realized that I was the only Wilderness First Responder in the group and the injured one. I had to be patient as well as doctor. It was time to make myself calm down and assess the situation.”

After throwing the switch on their emergency beacon, two of Stubbs’s partners began hiking back to cellphone range, and two made her a nest of sleeping bags and waited. The first responders arrived in just two hours. They discovered a deep gash in her thigh, a pint of pooling blood, and signs of a spinal injury. Two more SAR crews arrived two hours later. By dusk, they’d rigged a complicated network of pulleys to raise Stubbs up to a level platform where the 22 rescuers could begin hauling the litter down the rocky trail. They returned Stubbs to the trailhead 15 hours after her fall.

A year (and countless hours of physical therapy) later, Stubbs is back in school as a geography major and back on the trail, leading trips for her club and even testing gear for BACKPACKER. “I’m now a stronger hiker and a big safety advocate. I just secured a grant for the Hiking Club, my school’s oldest student-run organization, that will give our members deep discounts on avalanche safety and Wilderness First Responder training.”

Take it from me…

>> You always hear that pain is temporary, and glory is forever. Well, pain can last a damn long time.

>> There are all types of risks. Don’t fixate on just one. Backcountry travel is unpredictable, which is part of why we go there. It’s rewarding to figure out how to move and live in the wilderness safely. My mistake was having tunnel vision—the only danger I had on my radar was avalanche. I pinpointed every possible avalanche path, but ignored the conditions on a 45-degree slope I should’ve known would be difficult if not impossible to self-arrest on.

>> “Walk long enough in the hills, and you will find the tiger.” It’s cheesy, but this proverb means a lot to me now. I logged 800 miles in Rocky Mountain National Park and the Indian Peaks Wilderness before my accident. Evaluate every step. Experience doesn’t protect you from disaster.

>> Five is the ideal group size. If one is injured, you have two to stay and two to go get help.

>> A recovery period is an opportunity. I thought about how to make a difference in the outdoor community. Hiking is fun, so I decided I didn’t need to play marketer—I needed to make it more accessible and safer. That’s why we have a free gear-rental program, experienced trip leaders, and now subsidized medical and avalanche training. I’m also in SAR training.

>> Banana bread is almost as good as morphine. A rescuer gave me a homemade piece. The gift did so much to lift my spirits.