Six Decades Ago, Glacier Grizzlies Killed Two People in a Single Night—and Changed How We Thought of Bears Forever

Scratches on a tree in Glacier National Park (Photo: Mark Newman / The Image Bank via Getty)

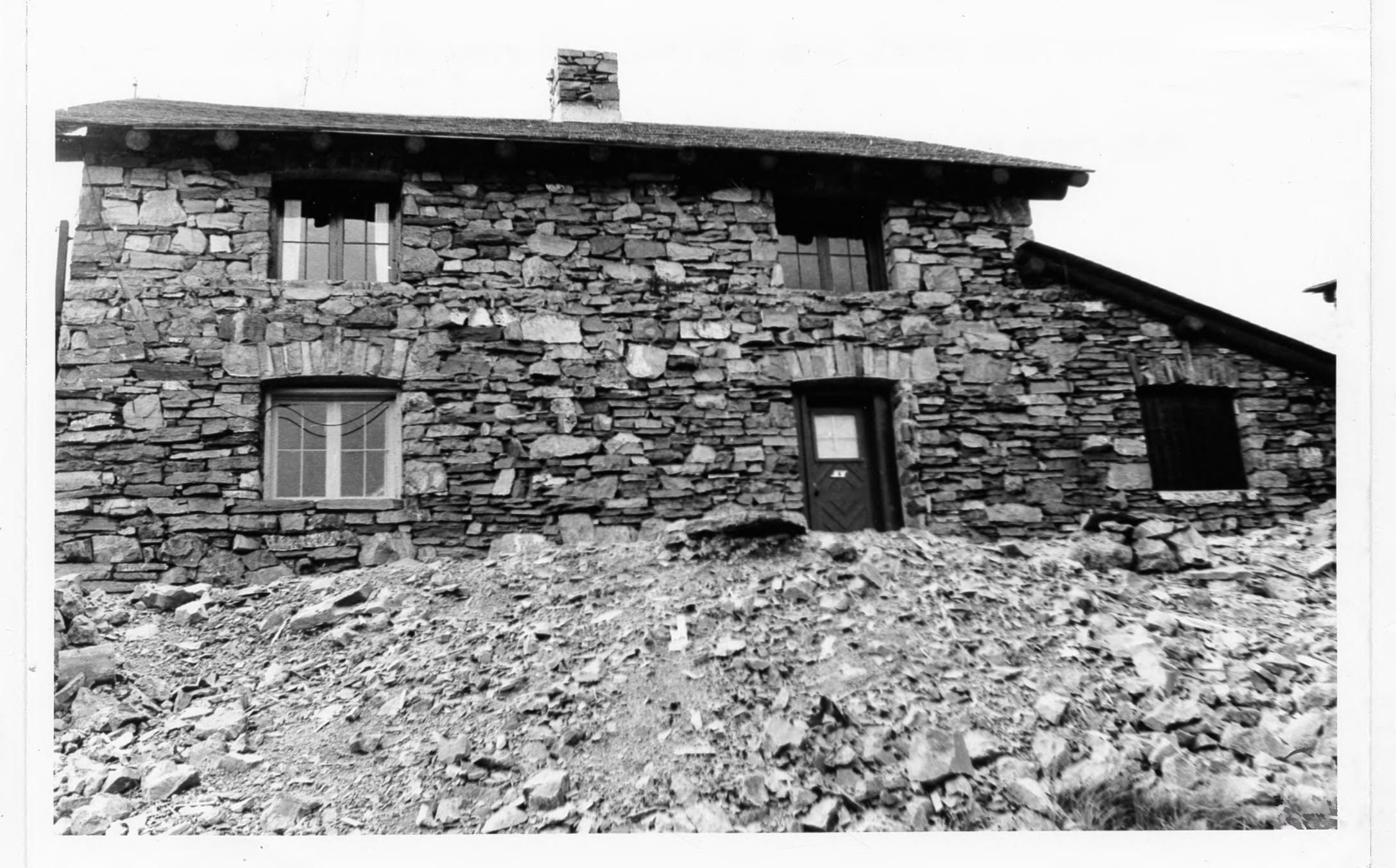

It was August 12, 1967, and Julie Helgeson was a bright, happy 19-year-old who was working in east Glacier for the summer. Helgeson and her friend Roy Ducat had decided to spend the day hiking to the Granite Park Chalet, a rustic stone building perched high on the west side of the Continental Divide. After a few beautiful hours on the trail, they arrived and spread their sleeping bags out in the open air at the campsite near the chalet.

About 10 miles away, Michele Koons was setting up camp at Trout Lake. Koons, also 19, had joined some of her friends who were working in the Lake McDonald area for an overnight hike. They had likely heard stories of a bear that had been harassing visitors there, but they weren’t worried. Everyone working in the park knew that bears could be pests, but ultimately, no one considered them dangerous.

By the end of the night, both Koons and Helgeson would be dead, mauled to death by Glacier’s largest predator, the grizzly bear. The women were the first victims of a fatal grizzly attack in the 57 years since the government had formally established Glacier National Park. What really separated these incidents from every prior North American bear encounter was that these two women were attacked by different bears on the same night, 10 miles apart. The double fatality would forever alter our perceptions of grizzly bears’ relationship with humans in the national parks. That evening would pass into history as the ‘Night of the Grizzlies.’

The Granite Park Chalet sits along Glacier’s Highline Trail, a roughly 11-mile route that connects Logan Pass to the lower Going-to-the-Sun Road. If you start hiking the trail at Logan, you get to enjoy 7.5 miles of alpine vistas, glacial bowls, wildflowers, and wildlife like mule deer, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, marmots, and the occasional black or grizzly bear. The chalet itself sits on the treeline, at the top of about 4 more miles of trail that connect back down to the Going-to-the-Sun Road.

That summer, Tom and Nancy Walton were running the Granite Park Chalet. The young couple was in their early 20s and upon arriving at the chalet, park officials instructed them on the new protocols for removing food waste. In the past, the park had simply placed leftover scraps in a pile not far from the lodge, and visitors would watch as bears showed up at night to feast. Now, the NPS was changing its attitudes toward feeding bears and other wildlife, and Tom was told to incinerate all food waste. But the Waltons ran into a problem: The incinerator that the park service had purchased for the season was far too small to handle the refuse of even a handful of guests. Before long, the staff at the chalet was dumping the food waste in a gully not far from the lodge. It only took a few days for the grizzly bears to start showing up every single night.

Roughly 10 miles away, at Trout Lake, a grizzly bear that had spent the early part of the summer feeding on human food in trash cans at a small village on the north end of Lake McDonald had moved up to the lakeside campsite. Throughout the summer, the relatively small and mangy grizzly bear tore through tents, backpacks, and lunchboxes in its search for high-calorie human food, terrifying dozens of visitors in the process. Many of those visitors complained to authorities, but from what we can tell, the park largely ignored them. Most of the rangers still saw grizzly bears as nuisance animals, creatures that had the potential to be dangerous but weren’t likely to actually do harm to people, and they had 50-plus years of data to support that idea. The bear would continue its escalating harassment of visitors until the night of August 12.

That night, Julie Helgesen woke to the sound of a large grizzly bear walking around their campsite. Just as she came to, the bear bit into her friend Roy, shaking him back and forth like a dog toy. Helgesen screamed, and the bear turned its attention to her. The animal went back and forth from one screaming teenager to another before settling on Julie and dragging her into the woods until her screams faded in the darkness.

Ducat ran to find other campers, and then sprinted up to the chalet for help. It would be hours before rangers arrived and rescuers finally felt secure enough to go back to the attack site. There, they found Julie, who had lost a massive amount of blood and was barely hanging on to life. She was taken back to the chalet where three doctors who happened to be overnighting quickly went to work trying to save the dying girl. But their efforts were not enough and Julie Helgesen was pronounced dead at 4:12 a.m. on a makeshift hospital bed in the chalet.

If the group at Trout Lake was certain that the bear that had been prowling the area wouldn’t be a problem, they found out otherwise when it crashed their dinner, forcing the campers to grab their gear and set up elsewhere. Still, the encounter wasn’t enough to change the group’s plans. Like Ducat and Helgesen, they eventually laid down to sleep under the stars.

Hours later, they awoke to hear the bear that had raided their dinner return to their site. Most of the campers were able to quickly scramble from their bags and climb nearby pine trees, but Michele Koons struggled to open her sleeping bag’s zipper and the bear pounced on her bag, pinning her to the ground. As it dragged her away, the rest of the group heard Koons scream that the bear had taken her arm off. The final words she said were “oh God, I’m dead.” After that, her companions said, they had to listen to the animal kill and consume their friend in the nearby woods.

Following the deaths, the park closed trails to and from the Granite Park Chalet and Trout Lake. Rangers immediately mobilized to hunt down the bears thought to be responsible. At the chalet, that process was relatively straightforward: From the safety of the building’s balcony, park personnel shot and killed all 3 of the bears that had been regularly feeding at the chalet. The bear at Trout Lake presented a much bigger challenge, charging the rangers tasked with hunting it down multiple times before they finally shot and killed it.

The fallout from the attacks didn’t stop with the bears’ deaths. The incident left the Glacier National Park community and the NPS as a whole reeling as officials tried to make sense of what had happened. Bear biologists around the country were quick to label two deaths in one night as a terrible coincidence, but that didn’t stop other theories from making it out into the news. Park officials, rangers, reporters, naturalists and armchair experts publicized their own hypotheses about lightning, wildfires and even menstruation. It seemed improbable that mere chance would lead to two deaths on one night after 50 years of relative peace.

But even though the bear attacks that killed Helgesen and Koons on the same night were a coincidence, the circumstances that led to them were not. Poor garbage disposal and food storage had created a powder keg of bear danger in the park. Bears that are able to regularly gain access to human foods become “food-conditioned” as the high caloric value of people’s provisions and the ease with which the bears get it lead them to start taking risks that wilder bears would likely avoid. The animals that killed the two teenagers had begun to associate humans with food, becoming both unnaturally comfortable and aggressive with people

The shocking outcome of the Night of the Grizzlies spurred the NPS into action. Almost immediately, the agency took measures to prevent food-conditioning in bears and to educate visitors about the potential danger of the wildlife with whom they shared the park. Dozens of new policies went into place: Parks began to close trails immediately following reports of bear activity, and staff killed or relocated problem bears after their first offense. Glacier brought in bear-resistant garbage cans, installed steel cables for campers to hang their food, and established a permit system for hikers spending the night in the backcountry. In a real way, that night and its aftermath set the groundwork for the bear safety practices we follow today.

As a bear conflict expert, I and many of my colleagues have struggled to find the right way to tell this story. Yes, it’s shocking, but that’s not all it is. The famous biologist E.O Wilson once said that rather than fearing predators, we “love our monsters” because our fascination with them helps us to stay prepared. That’s why stories of attacks and encounters with wild animals are riveting to nearly everyone, and have been throughout human history: They hold valuable information that can help people avoid mistakes while they are recreating in the outdoors. When we understand tragedies like this one, we can be more prepared while venturing into the backcountry and sharing space with its wildest inhabitants.

Wes Larson is a wildlife biologist specializing in human-bear conflict and co-host of the podcast Tooth and Claw. Listen to him discuss the Night of the Grizzlies in their series on the incident.