The Alaskan Non-Profit Saving State Parks

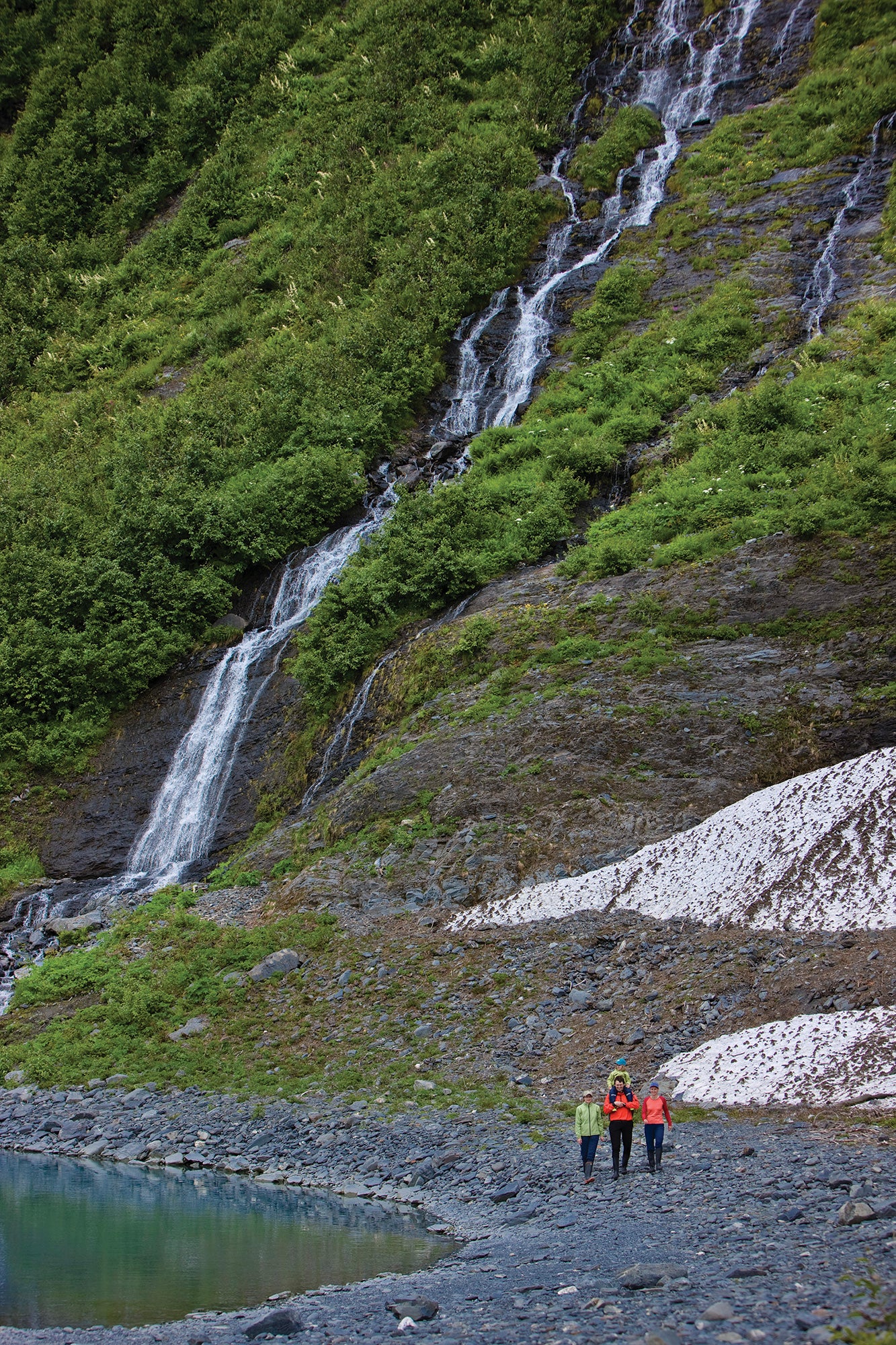

'Alaska Stock Images / Agefotostock.com'

At its best, the Shoup Bay Trail is a sampler of what makes Alaska great. For 10 miles, the route traces the shoreline of Valdez and Shoup Bays, passing through alder forest and flower-filled meadows on its way to views of Shoup Glacier. But last summer one thing was missing: the trail.

The path, overgrown with spiky devil’s club and cat’s claw, represented one small portion of Alaska state parks’ $65.1 million in deferred maintenance, but the four-person crew that showed up to tackle it in the summer of 2017 hadn’t been sent by the state. Instead, they were working for Valdez Adventure Alliance, a local nonprofit experimenting with a new way of keeping Alaska’s public lands open.

Alaska’s state park system is the biggest in the country, managing some 3.6 million acres. Unfortunately, its budget—$14 million in 2017—is minuscule by comparison, a fraction of the $522 million that California will spend on its parks this season.

“Everybody’s been working to tighten their belts and do what they can to cut costs,” says Ethan Tyler, director of Alaska’s Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation. The division has turned to private operators, generally locals, to run 26 of its parks. Those that don’t find takers risk slipping into “passive management,” which is as bad as it sounds.

Private enterprise has been part of America’s public lands since 1916, when Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, introduced concessions to the national parks. They’re now commonplace, from hotels and restaurants to buses and backcountry guides. But in the past decade, a few politicians have gone further and proposed privatizing the operation of entire park units. Advocates argue that privately run parks like Alaska’s cut overhead and reduce the burden on taxpayers.

Some contend that the profit motive can be a force for good. Warren Meyer, president of concessionaire Recreation Resource Management, says that dependence on fees creates an incentive for commercial operators to put users first. “In our company, 100 percent of the revenues we receive is from visitors, which means that if we don’t run a good operation that is attractive to visitors, we don’t make any money,” writes Meyer on his blog, parkprivatization.com. Private operators don’t own the parks they run, and user fees are set by the government.

Opponents counter that private operators don’t pay their fair share of maintenance, allowing them to reap profits while leaving taxpayers to foot the bill. A review by the Center for American Progress found $389 million in deferred maintenance at concessionaire-operated facilities throughout the national parks. Others worry that privatization is the first step toward a stealth takeover of America’s heritage, such as in 2016, when Yosemite spent $1.7 million on new signs after the outgoing concessionaire, Delaware North, claimed trademarks on the names of several of the park’s iconic sites.

But there’s a third way. When Alaska state parks announced in 2015 that it was searching for permitees to manage three Valdez-area parks, including Shoup Bay State Marine Park, it was a local nonprofit, not a corporation, that answered the call. Founded just months earlier, Valdez Adventure Alliance’s mission is to promote outdoor sports as an economic alternative to extractive industries.

For Valdez, the parks represent income: Roughly 100,000 people visit them every year, contributing an estimated $5 million to the local economy. “We felt it would be devastating to have these park units close,” says Lee Hart, VAA’s executive director. Rather than allowing a commercial operation to cherry-pick the most profitable sites, VAA argued that the state should give priority to groups willing to manage the entire package. After some discussion, the parties inked a two-year contract.

Nonprofits have long lent cash-strapped states a hand in maintaining parks. But with this agreement, Valdez Adventure Alliance became the only one in Alaska to run all aspects of a park, from carting away trash and stocking bathrooms to collecting campground fees.

The most serious challenge, however, was simply keeping the trails open. “Valdez is a subarctic rainforest, and in the summer, vegetation grows incredibly quickly,” Hart says. In Shoup Bay, it took a crew of contractors three weeks of “heroic brush-cutting” to clear a 7-mile section.

Soon, VAA faced another crux: funding. It became clear to Hart that, without state money, user fees from campsite and cabin reservations wouldn’t be enough to cover their operations. Locals chipped in, with a few restaurants pledging to donate 1 percent of their profits. VAA also secured a $40,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation—cash unavailable to for-profit operations.

Today, Shoup Bay State Marine Park is in better shape than when VAA took it over; the trail reopened last summer, and the organization is in talks with the state to renew its contract for another five years.

Both groups agree that they don’t want the nonprofit to run the parks forever. But with Alaska’s financial future still uncertain, will the state be able to take them back anytime soon?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Tyler says