Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

This is the story of an alleged kidnapping and rape on the Pacific Crest Trail. No charges have been filed against the alleged perpetrator. The accuser died on February 7, 2019. Prior to the alleged crimes, the alleged perpetrator was accused of mistreating a number of other women, but was never criminally charged or convicted for such behavior. This story is based on statements the accuser made prior to her death, interviews with more than 20 witnesses, and a review of public records. The alleged perpetrator has not responded to requests for comments.

At first, he seemed like a nice guy. “He struck me as solicitous,” Kira Moon said. “A giving, caring person. You got the impression he was service-oriented.” James William Parrillo, 53, had an intriguing past, as well. He said that he was a retired Navy SEAL and that he’d worked as a deep-sea diver for Greenpeace. He was fairly wealthy, too, he added in an understated way. He’d just sold a home in Santa Cruz for $4.5 million. He didn’t have access to the money just yet, however—it was still in escrow—and he was in physical pain. In a windstorm earlier that month, March 2018, he’d been blown off a cliff in Mt. Laguna, California, he told Moon. He’d broken some ribs and punctured a lung.

So now Parrillo, an impeccably neat, balding man, 6’1” and lean, with a salt-and-pepper goatee and a steady, shark-eye gaze, was temporarily living, along with Moon and a dozen other would-be thru-hikers, at Carmen’s Garden, a Mexican restaurant in Julian, California, 77 miles from the southern terminus of the Pacific Crest Trail, where Moon had begun her hike 10 days before. Did anyone wonder why a professed multimillionaire was crashing at a cheap hippie restaurant? Well, the vibe at Carmen’s was loose and trusting. By day, the hikers waited tables and washed dishes. In the evening, they quaffed beer, then unfurled their sleeping bags to sleep clumped close together on the floor. The vague scent of unwashed human pervaded the room, along with the easy, good-humored kinship that imbues so many hiker gatherings. Moon felt happy, at ease. She began to like James Parrillo—and in time, it seems, he sensed this.

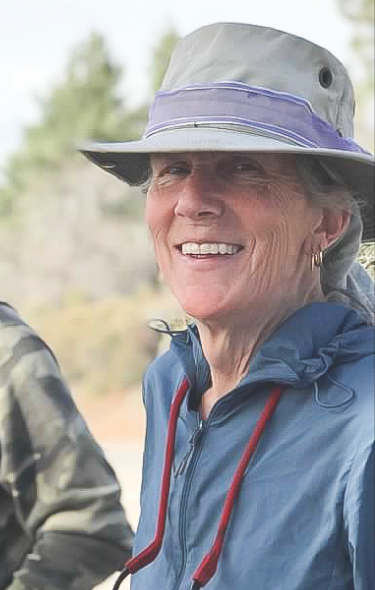

After three days, according to Moon, Parrillo suggested that the two of them hike the PCT together—when he healed up, that is. Couldn’t she wait there in Julian just a couple more days for him? The proposal didn’t seem amorous. There’d been no flirting, according to Moon. She was 62 at the time, eking by in San Francisco on a $900 monthly disability payment, and was still trying to figure out exactly how she felt about the guy. She wasn’t sure at first, but she would eventually write to a friend about the younger Parrillo to joke, “I’m joining the cougar club.”

Moon waited in Julian for Parrillo, and then after a few days at Carmen’s they began hiking north. Stored on Moon’s phone was a photo she’d taken of him. She wanted to post it on Facebook.

“Wait a few days,” Parrillo told her.

She waited a week. Then, as they hiked north, she posted the photo. Parrillo went berserk. At a remote campsite, he screamed at her for hours. He insisted that she stare him square in his eyes as he berated her, and he laid out a wild rationale for his rage. He was gay, he told Moon, and he’d come to the PCT to escape a host of pursuers. The Navy was after him because he’d lied about his sexual orientation, and the media was after him too because a rumor was afloat that he was Caitlyn Jenner’s lover. Why, why had Moon tipped them off with her Facebook post? “You’re ruining my life,” he said, according to Moon, who tried to meet all of Parrillo’s outbursts with an unruffled coolness. “I come from an Italian family with a lot of dignity, and now you’ve put a black mark on my family. I can’t go back to them because of you.”

Parrillo, who did not respond to repeated requests for an interview, is of Italian descent. But nearly everything else he told Moon is a lie. According to interviews with 20 people who know the alleged perpetrator or his victims and a review of public documentation, the man is in fact a drifter, and poor. It’s very unlikely that he broke any ribs last spring. The U.S. military has no records indicating that Parrillo ever served. Rather, his past suggests a lone wolf, a charming but violent con artist who, over the past 30 years, has roamed the country under myriad aliases, leaving fear and wreckage in his wake. At least seven women have accused him of kidnapping and rape. Two of these women said Parrillo held them captive for more than a year, and that he sired a child with them.

Parrillo has never been charged for mistreating women, but the accusations that women have made against him—to me and to others—are remarkably consistent. They depict him as a dangerous man and fantastical liar who survives by scamming anyone he can. But Kira Moon didn’t know any of this as she hiked down the Pacific Crest Trail with her new friend.

Aside from the occasional rattlesnake and lightning bolt, we think of long trails as safe. And while they generally are, they do, every so often, attract criminals eager to capitalize on the trails’ seclusion and the casual trust that builds up between hikers along routes such as the AT, the CDT, and the PCT. Since 1974, there have been 12 murders, including one in May 2019, on the nation’s most popular footpath, the Appalachian Trail, which draws roughly 3 million visitors a year. But how many sexual assaults? It’s impossible to say. Unlike murders, which lead to investigations, rapes often go unreported out of the victim’s confusion, shame, or fear to come forward.

No reliable statistics size up the prevalence of rape and crime on the long trails, but nationwide, 77 percent of all rapes go unreported. Of the ones that are reported, only about one-fifth are prosecuted (trials are long and costly, and lawyers don’t want to gamble on long-shot cases). Only half of all prosecuted cases result in convictions. All told, only about .7 percent of all rapes and attempted rapes end in a felony conviction, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network’s analysis of U.S. Justice Department statistics.

Kira Moon’s story of sexual violence is one of the many that will never be prosecuted. It begins in 2007. Moon was working as a sculptor’s assistant in San Francisco and frequently lifting large chunks of bronze—a strain upon her slender, bony frame. (A gentle and elfin individual, Moon was 5’8” and weighed 115 pounds.) One morning, she wrote on her blog, she woke up with “my back, neck, shoulder, and arm half paralyzed, burning, buzzing, and numb.”

The pain was never diagnosed to Moon’s satisfaction. It persisted for years, and Moon began to rely on a motorized wheelchair to navigate San Francisco. Unemployed now, she survived on her disability check as she inhabited the opiate haze of her pain meds and bunked down in a substandard $600-a-month basement apartment, obliged to toil upstairs to use the bathroom or cook.

It was a difficult existence, but not without love. Back in the 1980s, when she was romantically partnered with a woman who had a young son, Moon formed a relationship with the boy, Jason Storm. Now 40, Storm lives in San Francisco and works as social worker and drug treatment specialist, and sings in a punk rock band, Space Toilet. Moon described him wryly as “the un-son.”

“Kira was there throughout most of my childhood,” Storm said. “She was the one who taught me about music and art. She was a huge influence.”

Moon spent her days going to medical appointments until, in 2016, she found herself contending with a new doctor who refused to renew her oxycodone prescription. She suffered through cold-turkey withdrawal, drinking red wine to patch herself through. And eventually, she rejoiced on her blog, she began feeling stronger “mentally and physically. I quickly regained the stamina I had lost during my convalescence, and then some. I was regenerating.”

By early 2017, Moon told me, she was still unable to sit or stand for prolonged periods. She could walk with ease, however, and abandoned the wheelchair. She even frequently hiked the strenuous 10-mile round-trip from her home to the summit of San Bruno Mountain, elevation 1,319 feet. The walking was a bright spot in an existence that was still, even after Moon conquered her addiction, a little rootless and solitary. “I was very unsettled,” Moon said of that time. “I wanted a new life.”

Soon she began to dream of hiking the long trail from Mexico to Canada. Never mind that she had no backpacking experience, or that Jason Storm thought she was crazy. She is at heart an adventurer. When she was 16 and living a quotidian middle-class life with her parents in San Francisco, she ran away for eight weeks, hitchhiking to New Jersey and back. Moon identified as male at the time. When she was 20, she took another bold move and underwent sex reassignment surgery, changing her legal name from Keith Marchington to Kira Marchington-Moon.

Eventually, Storm relented and created a GoFundMe page for Moon’s hike. He raised $785 for gear, and on March 18 she showed up at the Mexican border, determined to walk 2,650 miles to Canada. She wasn’t ready, exactly, but she was willing to take a gamble. “I was poor,” she said. “I was starving. And I thought that maybe the trail would lead me to a new life—to new people, a new living situation in the countryside, even. I’d done this before—gone out on God’s little fingertip, I mean, and dared Him to flick me away. I was ready to take a risk.”

The first 100 miles were challenging for Moon, who quickly assumed the trail name Steel, on account of her unusual shoes—light metal slippers made out of stainless steel mesh that she liked because they were artisanal.

Hiker Renee Schmetzer, who started the trail with her, remembered, “She was very competent about water and food, but she didn’t know how to set up her tent. One night, she left to go to the bathroom and got lost coming back. She had to sleep in the bathroom.”

Moon’s frail appearance compounded her problems. At the Mexican border, said hiker Thomas Moore, a trail angel told him, “Stick with Kira. She looks so unprepared she’s going to kill herself.”

Along with his friend, Moore hiked with Moon for 10 days. She struggled, according to Moore. She did some hitchhiking en route to Julian. And when she arrived at the Mexican restaurant there, she was weary and weak. Did Parrillo take notice? Well, he’d certainly gone after vulnerable types before.

In 1988, Parillo was 22 and visiting Pasadena, California, when he met a young woman interning as a youth minister. He posed as a refugee from the Mafia and said he needed help, the woman recalled. In time, he beseeched this woman, who requested anonymity out of fear, for a ride to the airport. Somehow, he convinced her that a vengeful Mafioso was chasing them. After he pressured her to marry him—“for your own safety,” he assured—he allegedly raped her. He stole her address book and then forced her to call everyone she knew, to beg for money that would keep them afloat as they scrambled about the U.S., living, the woman said, at 20 different addresses over the next three years. At one point, she said he told her, “If you leave me, I’ll hunt you down and kill everyone in your family.”

The woman never reported her abduction to the police, but was able to escape Parrillo in 1991, when she gained the courage to sneak out of a hotel room as he slept. In 1993, she had her marriage to Parrillo annulled.

A year later, Parrillo showed up in a Daytona, Florida, hospital, claiming he’d tried to kill himself by overdosing on anti-seizure pills. He was the first-ever patient of a nurse who had started the job that morning. Parrillo faked seizures, the nurse told me in a 2018 interview, but she was too enamored to detect his deception. “He was incredibly attractive,” she remembered, “and intelligent.”

When Parrillo asked the nurse for a ride to Orlando, 75 minutes away, the nurse breached professional standards and said yes. Another high-speed “chase” ensued—this time the make-believe pursuers were Navy police after Parrillo for going AWOL. The nurse escaped after three days, she said, only “because I used his story against him. I told him, ‘If they’re after us, we need to leave the U.S. You need to go steal a boat so we can escape to the Caymans.”

Early the next morning, Parrillo did as the nurse advised. Wielding a .38-caliber pistol, he boarded a yacht in a Fort Lauderdale marina and held nine people at gunpoint during a four-hour standoff that police quelled before anyone got hurt. According to a story in the South Florida Sun Sentinel, Parrillo placed his gun under the chin of the ship’s captain, Scott Schneck, and said, “I want to tell you goodbye.” Later, pleading insanity, Parrillo was acquitted of all charges and put back out on the street. In time, for reasons only he knows, he found his way to the Pacific Crest Trail.

For Moon, Parrillo’s attention was an unusual but welcome detour. While she partnered with women in her twenties and thirties, she’d spent most of the past two decades alone, convinced that she could never replicate a brief, intense liaison she shared in the nineties with a female artist many years her junior.

Was Parrillo, in his guise as a can-do military man, a good match for this free spirit? One thing is clear: He seemed to her like a safety blanket, a guardian to stand by her as she got her bearings as a hiker.

Seemed is, of course, the key word. A few days after Parrillo gaslighted Moon for the Facebook post, just outside Big Bear, California, she suggested she might hike solo toward Canada. Incensed, Parrillo grabbed her by the neck and punched her in the head. After she fell to the ground, he kept beating her. “He had a smirk on his face the whole time,” Moon told me, “like this was what he’d been waiting for, like this was Christmas for him.”

In the five months that followed, the two continued to hike together, always with Moon in front and Parrillo vigilantly behind her. She said that he raped her repeatedly and forced her to give him oral sex. He confiscated the SIM card from her cell phone, cutting her off from the outside world, and each time she spoke of leaving him, he beat her again. On September 16, she said, he slugged her hard enough to break bones. The claim is backed up by a September 26 x-ray that found four fractured ribs.

Moon was, it seems, hiding her terror beneath a demure facade. “I knew,” she said, “that if I went against him, he could snap my neck in two seconds.”

Before Parrillo got violent, Moon shared stories from her life with him. She talked about Jason Storm and also Storm’s girlfriend Brandi Valenza. The couple resides, along with Valenza’s 16-year-old daughter, in a cramped San Francisco one-bedroom, scraping by on their two incomes (Valenza is a bartender).

Parrillo proclaimed that he could rescue the cash-strapped trio. What if he just cut them a check for $100,000 once his real estate money came through? He directed Moon to call them as he stood nearby. Moon thought the offer was a ploy to ingratiate himself with her family, but what could she say? Soon Parrillo got on the line himself, dazzling them with hope as he pretended to arrange a bank transfer.

With fellow hikers, meanwhile, Parrillo peddled another fiction. He told them that he and Moon had been married for years, and on June 29, using Moon’s bank card, he bought her a cheap garnet ring to buttress the tale. The purchase sickened her.

Probably to keep other hikers from studying him closely, Parrillo did not move Moon steadily north. Instead, the pair ricocheted about in Southern California, hiking only around 30 percent of the time as they hitchhiked between trail towns—Idyllwild, Warner Springs, and Big Bear. Often, they’d linger all day by their tent so that Parrillo could scrub clean his hiking boots or fix tiny tears in his immaculate hiking shorts.

In trail circles, though, the travel details got lost in the mix and a myth emerged: Parrillo was a stalwart and selfless hero. In his online journal, a hiker named Pause describes Parrillo, who had taken the trail name Medic, as a “former military field doctor who’s been taking care of so many others that he himself has fallen weeks behind schedule. Among them is a tanned, wiry woman named Steel, who seems dangerously unprepared for the PCT, unable to carry her own food and water or hike more than five to eight miles a day. Medic’s sticking with her, part pack mule, part guide.”

Not everyone bought Parrillo’s act. When PCT thru-hiker Dimitri Lenaerts crossed paths with him in Big Bear, California, in July 2018, he expressed doubt as Parrillo bragged that he was nearly done with the PCT—that he’d started in February, in Canada, and hiked south through two snowy mountain ranges in the dead of winter. “I said, ‘That’s not possible,’” remembered Lenaerts, a 32-year-old chemist from Belgium, “and he just stood up and started shouting at me.”

Lenaerts was struck by how domineering Parrillo was. “Kira spoke maybe two complete sentences in the two hours we talked,” he said, “but I didn’t intervene. I decided, ‘She’s a grown woman. She can run away if she wants.’”

In early August, as Parrillo and Moon found themselves stalled by a forest fire, waiting a week in Mountain Center, California, Parrillo threw another public tantrum. “He was helping distribute bottles of water to fire victims,” remembers Pam Greyshock, a Mountain Center realtor, “and when somebody stole a case, he was outraged. He was pacing back and forth, talking to himself, throwing his arms in the air.”

Parrillo was mostly cool-headed in Mountain Center, though, and he took the reins as a small fire-refugee camp grew there, on the porch of the Paradise Valley Cafe. “He acted like he was God’s gift to everyone, but he was responsible,” said Neel Joshi, the cafe’s owner, who was away traveling during the 10-day power outage that the fire wrought. “He cleaned the bathrooms. He called me every morning to apprise me of what was going on.”

There were dozens of police officers in Mountain Center, lining the fire’s perimeter, and Parrillo prevailed upon them to give him special dispensation to drive into the fire zone to obtain provisions for the fire-stranded—a gas-powered generator, for instance. A horse got burnt, and Parrillo convinced a veterinarian he was capable of overseeing the animal’s medical care. “He had everyone fooled,” said Marlene Racca, a Mountain Center resident who allowed Parrillo and Moon to stay in her house for several days and then loaned Parrillo $1,000 she never got back. “He had a forceful, commanding presence.”

Racca added that, as Parillo worked his almost gymnastic con game, he often left Moon alone, sometimes for as much as an hour. “She could have just walked up to the police at any time and said, ‘Protect me from this dangerous man.’”

But by now, according to Moon, Parrillo had beaten her three times—and had sequestered her at a remote campsite each time to hide her black eyes. He’d seized control of her bank card, signing at one receipt, “Jay Moon.” She said he also told her, “I should kill you and bury you in the desert. I’ll kill your family. I have some shady friends who’ll come and take care of your kids.” He meant Storm and Valenza.

And there was something else, too: Parrillo was chummy with the cops. Once, after he hopped in Racca’s car to make a supply run, he asked the police what they wanted at Starbucks—and then came back with the requested beverages, along with some donuts.

Moon took no risks. She did not approach the police, fearful they would not believe her. In time, her reticence would elicit skepticism. One hiker, a construction contractor named Sydney Beck, said she saw Moon and Parillo kiss and hold hands. She was still a Parrillo believer even after I told her in late 2018 that Parrillo had multiple accusers. She followed up our phone call with a written message. “I think,” she said of Parrillo and Moon, “that it is very strange that they came back to Idyllwild at least twice. If there was something fishy going on with Jay, why would they do that?”

Janine D’Anniballe, a Colorado psychologist who often serves as an expert witness in rape trials, believes Moon’s claim that she faked affection for Parrillo. “When women find themselves in scary situations, gender role socialization kicks in,” D’Anniballe said. “It’s all about keeping everybody happy and not making a scene. If you run, you increase the risk of violence.”

After the fire died down, Moon was only sporadically in touch with Jason Storm and her notes were strangely detached and cool. “Far from being in danger,” she wrote to Jason that summer, “thanks to Jim, I am well fed, provided for, and having the time of my life. For the record, I’m surprised at your recent outpouring of ‘concern’ after all the years I lived in poverty and isolation and could barely muster a return call from you. It’s been literally decades since I actually felt like I had a family.”

Storm said he felt hurt reading that message. He thought, “We’ve built this great relationship and now you just want to throw it away.” But by now, after months of waiting for that $100,000 check, Storm’s girlfriend, Brandi Valenza, had a hunch that Moon was being manipulated. A heavily tattooed 50-year-old who describes herself as a “rocker chick,” Valenza kicked into detective mode. She plugged Parrillo’s name into internet crime databases. She talked to Parrillo’s relatives, and slowly she pieced together the man’s past.

In 1996, Valenza learned, Parrillo was the subject of a weekly TV show, Unsolved Mysteries. The episode described how he showed up at a Florida truck stop in 1993 and presented himself to a woman there, Valerie Earrick, as Angelo Anthony DeCompo, the millionaire scion of a Mafia family and also, thanks to a Gulf War combat injury, a deaf mute.

Earrick’s parents, it so happened, owned a new Camaro. Parrillo packed her into it and then drove her wildly about on what Unsolved Mysteries’ promo material describes as a “six state, 2,000-mile journey of terror.” Earrick survived, despite being repeatedly beaten, and according to Unsolved Mysteries, “Tony DeCompo vanished and is believed to have victimized other people.”

In 1997, Parrillo was briefly jailed in Virginia for “threatening the president of the United States,” Bill Clinton. In 2002, he was convicted of allying with a Los Angeles woman, Laura Michele Lyde, to kidnap Lyde’s two young children away from their father. Lyde was later exonerated. Parrillo was sentenced to three years in prison.

Eleven years later, Parillo presented himself as a one-time Greenpeace ecoterrorist in an interview with Dismantle the Beam Project, a pro-gun, Christian, conspiracy-minded website. In a 68-minute videotaped interview with Dismantle, the interviewer marvels with no basis that Parrillo spent “almost two decades” in “the U.S.’s most secure SuperMax federal prison.” Dismantle’s interview is now marked with an update: “It has been determined that James Parrillo fabricated his story.”

Not surprisingly, Valenza’s research made her worried. It was now mid-August, five months after Moon had started hiking and a month since they last credibly heard from her. Valenza launched a Facebook page, “Find Kira Moon,” and also created a timeline that exhaustively detailed Parrillo’s prosecuted and alleged crimes.

Did Parrillo know of Valenza’s campaign? It’s unclear, but on August 13 he fled the PCT, claiming—falsely, of course—that he’d hurt his leg. (It “swelled real bad,” he wrote Marlene Racca, his former host, as he recounted a fake visit to the hospital.) Dragging Moon along with him, he took a series of buses west to the California Coastal Trail. Then, once he got onto that 1,200-mile path, his behavior became “more and more desperate,” said Moon. “Every morning he’d wake up and change his plans.”

Now, he and Moon scarcely hiked at all. They spent several days hiding out in the trees behind the little-used Salmon Creek Guard Station, a defunct firehouse that sits within Los Padres National Forest, in Monterey County. “All he did all day,” Moon said, “is look at porn on his phone and talk about how he hated everyone. The worst part of the whole experience wasn’t being beaten. It was being in his presence all the time.”

Moon pretended Parrillo’s depravity didn’t bother her. “I impersonated a meek, gullible person, just so I could make him feel that I was trustworthy,” she said. “But I never lost a sense of who I was.”

Eventually, Moon’s acting started to pay off. “He began to trust me more,” she said. “When we went to a supermarket, he’d leave me alone so he could shop by himself.”

Parrillo’s trust in Moon was not new—he’d left her alone several times during the forest fire—but Moon’s sense of agency was. She had begun to see her captor as desperate and fragile. He was being hunted. This was apparent to Moon even if she didn’t know of Valenza’s detective work. “He was running out of ideas,” she said. “He began talking of slipping out of the U.S.—of going to Arizona to borrow a car and $10,000 from his father.”

On September 21, Parrillo took Moon to tiny Morro Bay, California, a short hitch from their Salmon Creek hideout, and left her alone and bruised at the Starbucks as he shopped for groceries. She timed his absence. He was away, finding food at Albertsons, for eight minutes—and so when they returned to Morro Bay to resupply five days later on September 26, Moon knew how much time she had to escape. She ran out into the parking lot. She thought of throwing herself in front of traffic, so she could beg a driver for help, but then she spied an urgent care facility. She bolted inside. Using the desk phone, she called the Morro Bay police, and they moved quickly. They nabbed Parrillo inside the supermarket.

An hour later, after Moon got x-rays at urgent care, she wrote to Jason Storm. “Please forgive my treatment of you,” she said. “I was kidnapped and all my messages were dictated and controlled by this vicious man, in order to separate me from you. I never would have treated you that way except under threat of death. Tell Brandi I’m so sorry. I hope you can understand and forgive me. I love you, my dear brave son.”

When she returned to San Francisco, Moon was haunted. “I keep seeing his fist coming at my head,” she told me in October 2018. “I have waking nightmares. I keep re-experiencing the beatings.” She contacted authorities in Monterey County, trying to get Parrillo convicted for the September 16 beating he gave her there.

A Monterey County Sheriff’s detective, Javier Galvan, interviewed Moon. According to Moon, he said that he would soon collect her backpack as evidence. Galvan never did. Investigators never asked for Moon’s medical records, and in all the interviews I did with more than 20 hikers, family members, trail angels, and friends related to Moon’s case, I did not speak to anyone who’d been interviewed by Galvan.

Jonathan Thornburg, a spokesman for the Monterey County Sheriff, declined to comment. He explained that the investigation is still open, but when I contacted a veteran prosecuting attorney, describing Moon’s case, she said, “It sounds like the investigators are done. There are two approaches a DA’s office can take,” said Alice Vachss, who is also the author of Sex Crimes: My Years on the Front Lines Prosecuting Rapists and Confronting Their Collaborators. “Either you go after every person you think is guilty, or you only prosecute if you think you have a good chance of winning the case.”

Monterey County is, Vachss conjectured, taking the latter, more prevalent approach. Moon “would not be particularly sympathetic to juries,” Vachss said. “She was with the guy for over five months, and in long-term situations like that juries will think, ‘It was a relationship. She could have fled if she wanted.’ Juries are always looking for the perfect victim,” Vachss added. “In this case, the prosecutor would need to get the jury past a whole bunch of things—her being transgender, her being on disability. It would be hard.”

Moon didn’t have much time to dwell on criminal justice. In the fall of 2018, in the wake of her kidnapping, she was homeless and drifting around San Francisco, from one friend’s couch to another. She’d planned on paying her rent from her disability money as she hiked, but Parrillo had spent it all, so she’d been evicted.

I kept in touch with her after my visit to San Francisco, and she seemed a bit lost. “I’m being treated for PTSD officially now,” she wrote to me. “It’s a long process … There’s a lot of mess to clean up in my head.” She moved into her sister’s home, a double-wide trailer on Bethel Island, near San Francisco. She retained her sense of humor, though, and on January 26, 2019, after giving me a weather report—“It’s been chilly here, and rainy”—she took a larksome swipe at Parrillo: “I hope that homeless son of the devil is freezing his ass off.”

It was the last time I heard from her. On February 7, Kira Moon died when an electrical failure caused the trailer to catch fire. Brandi Valenza blames Parrillo. Without him, she said, “Kira wouldn’t have been homeless. She wouldn’t have been in that trailer.”

James Parrillo is, in any case, still at large. After being nabbed at Albertsons, he spent only one night in the Morro Bay Jail. (The police didn’t have enough proof to charge him with a crime, and Moon never pursued a restraining order.) Not long after his release, he launched a new Facebook page using his real name along with an array of PCT photos Moon took of him. Last spring, Parrillo hiked portions of the Continental Divide Trail claiming to be a stage IV cancer victim. His Instagram feed, @walking_for_cancer_awareness (since deleted), once boasted more than 1,400 followers and scores of upbeat selfies that showed Parrillo grinning as he stood beside a succession of unsuspecting new acquaintances, though online groups like Missing on the PCT continue to track his movements and post warnings about him on Facebook.

But it’s another image, not on Instagram, that chills me most.

On November 1, 2018, I received, via email, a picture of Parillo taken that morning in Warner Springs, California, a PCT trail town. In the photo, shot by a woman who picked him up hitchhiking, he is shouldering a green backpack and wearing sunglasses, with the dry mountains rising behind him. He’s just a few weeks removed from the jail in Morro Bay, and his gaze seems shadowed by a vengeful distaste.

In a few hours, though, he’ll begin chatting with other hikers. He’ll meet someone, it’s almost certain, someone who expects nothing but the best from a fellow hiker. Someone who can’t imagine the worst of humanity encroaching on the best of the wilds.

Bill Donahue contributes frequently to BACKPACKER.

Correction: The original version of this story listed Kira Moon’s height as 5’6″. She was actually 5’8″.

From 2022