Growing Up on the PCT

My daughter, Caroline, was striding far ahead of me as dusk settled on the Pacific Crest Trail in Southern California. After hiking 25 miles that day, over a rocky, hilly desert, I was exhausted and felt the weight of my pack—but Caroline, 17, kept charging into the horizon, with a load just as heavy.

“Hey, Caroline, wait up!” I called. “Don’t get too far ahead!”

No response. She couldn’t hear me.

“Caroline!” I shouted, louder this time. “Slow down for the elderly!”

It was too late, and since shouting had slowed me down she was now even farther ahead. My mind conjured cougars pouncing on her, rattlesnakes biting her. And as I trudged along after her, I thought of the first time she had carried her own pack. It had been a decade earlier, although it seemed as if only 10 minutes had passed.

Caroline’s take: I often wonder what my dad thinks about while hiking. I’m pretty sure it’s more along the lines of “what snacks can I eat from Caroline’s pack without her noticing,” or “what dangerous country should our family spend next Christmas in?”

She was 7 years old and insisted on carrying a backpack herself on one of our family’s overnight hikes in Oregon. The rest of us laughed and suggested, a bit too patronizingly, that this would be too much for her.

“You really think you can carry your pack?” one of her big brothers needled her. “You’re too little!”

“First uphill and you’ll be begging us to take it back,” her other brother chimed in.

That settled it. “I’m carrying a pack,” Caroline declared firmly.

So we loaded a soft pack with her sleeping bag and some clothes, trying to keep it light. She bounced up the trail for the first few miles like a helium balloon, but then protested that her pack was getting heavy. I removed the sleeping bag, and she continued for a couple of miles—then paused and asked if something more could be taken out. So we took out everything, and Caroline now had an empty pack. That worked fine for another mile, but then she paused.

“Could someone carry my pack for a bit?” she asked in a small voice.

I stuffed it into my own, but her brothers had a good time teasing Caroline about that.

Lies! I didn’t ask for my pack to be carried. It’s true I lagged behind, but the story changes every year—next, my brothers will claim to have carried me and my pack the whole way!

Sadly, this is a favorite Kristof story. There are better tales—like when my brother removed his shoes to cross a creek and they disappeared over a waterfall. To this day, we know the spot as “Gregory Shoe Creek.”

Returning from my reverie, I noted that Caroline had now completely disappeared into the distance. The first stars were coming out, and I began to worry. Would she have the sense to stop before it became pitch black? What if she set up camp 75 feet off the trail and I walked right by her? Would we find a decent camp spot this late? I grumpily reflected that there were significant disadvantages to her growing strong and leaving her dad in the dust.

I tried to speed up to catch Caroline, but my legs wouldn’t have it. The trail wound over hills and I couldn’t see far ahead. Soon I would need to pull out my headlamp. Damn teenagers.

And now I had a bigger concern: What if she decided to hike the rest of the PCT without me?

My trail name is Scribbler (because I’m a writer who often covers global hot spots), and Caroline’s is Tumbler (because she’s a gymnast, not because she’s always falling over her feet). Scribbler and Tumbler decided in 2012 to section hike the PCT. Caroline was 14 that summer, and I was 53, and we both had backpacking in our blood. I grew up in Oregon, hiking chunks of the PCT, and wanted to transmit the experience to my own kids a generation later.

I thought Scribbler and Tumbler sounded good together, but I didn’t realize that on my own I’d just seem like a perennial incompetent who lacked basic motor skills. Worse, this is not entirely untrue.

The paradox, of course, was that an essential element of my own youthful treks was that there were no grown-ups along, while I selfishly wanted to participate as my kids enjoyed similar experiences.

You can imagine how horrified my friends’ parents were when, in middle school, I echoed my dad’s idea, suggesting that as a fun “girls’ night out” activity we could go on a no-grown-ups-allowed, 150-mile backpacking trip.

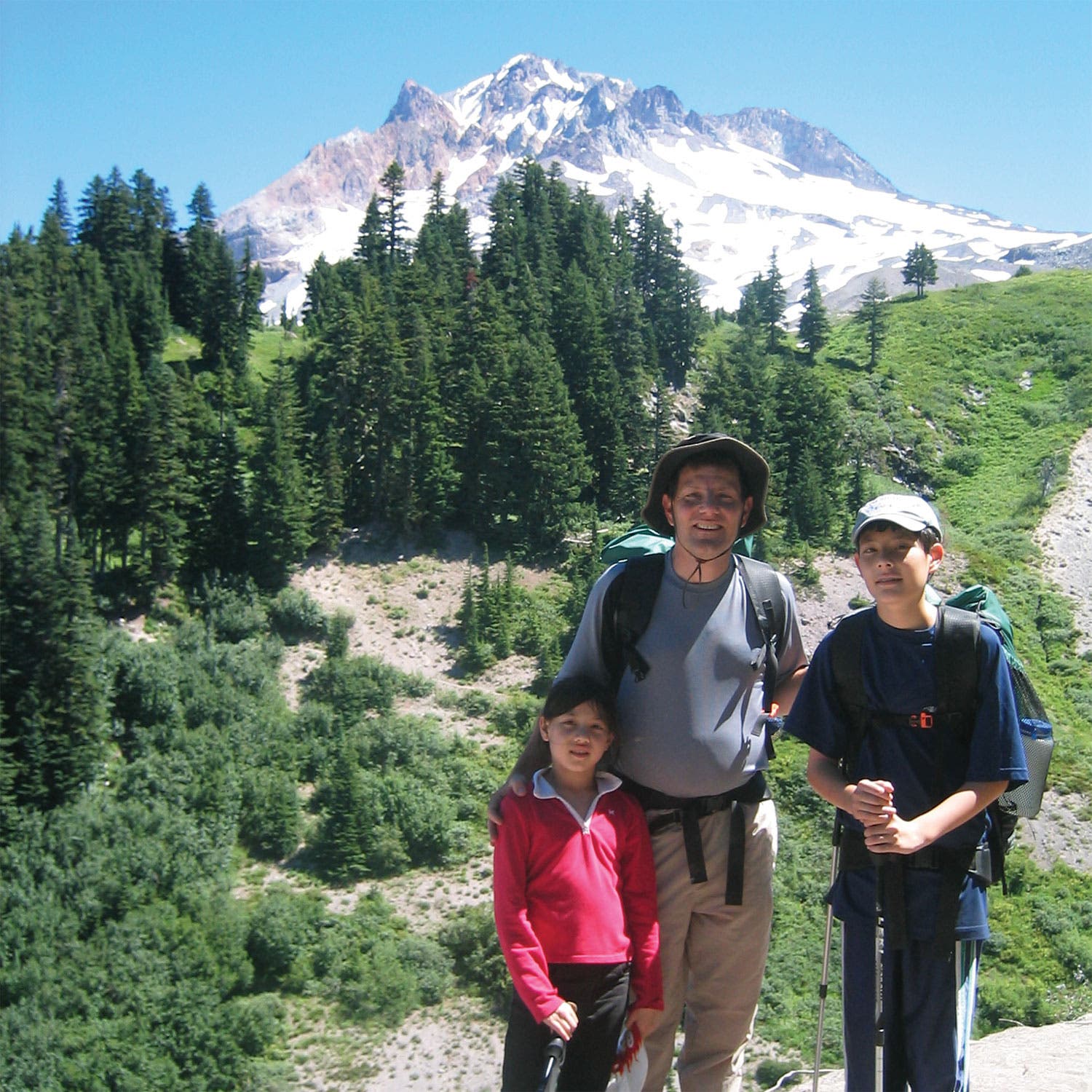

My wife and I began taking our kids backpacking when they were young. We brought Caroline on her first overnight trek when she was just a year old, and then every summer after that. When she was in elementary school, we took her on a three-day, 40-mile hike around Mt. Hood, and later on a 100-mile hike on the Oregon PCT. While the boys enjoyed hiking, they developed other priorities in their teens, but Caroline’s enthusiasm for backpacking only grew as she got older.

At first, our section hike was intended to traverse only the 455 miles of the PCT in Oregon: That seemed doable and would take us over new stretches of trail. Very quickly, we decided to add Washington as well—but I had some doubts about whether we would manage this. Our sons were becoming busy with college and summer jobs, and I worried that Caroline would fall prey to the real world as well.

Well, I am now on LinkedIn and very employable.

Anyway, what teenager wants to spend quality time with her dad, year after year, getting bitten by mosquitoes? I could already see that Caroline was growing more independent and inclined to spend time with friends rather than family. I wasn’t sure that we could sustain our trek summer after summer and complete the trail.

Somehow, vacation in the wilderness seemed luxurious after Thanksgiving at a Haitian cholera hospital!

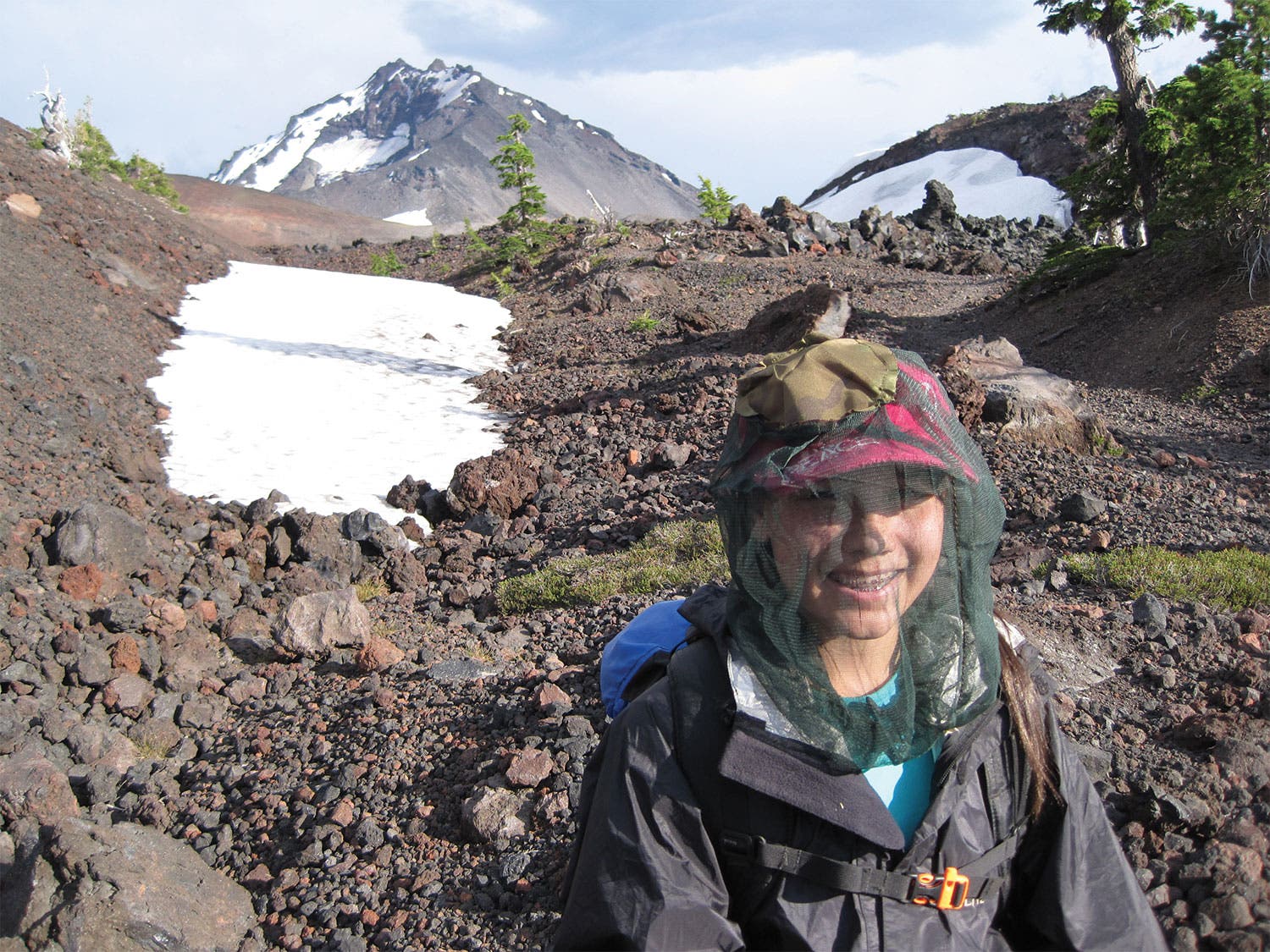

Our hiking window that first year was early in July in what turned out to be a big snow year, and we hadn’t appreciated how much of it there would be. We completely lost the trail under 3 feet of snow in the Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon and headed north by map and compass. Back then, we didn’t have apps like Guthook and Halfmile to locate the trail, so it was the most difficult hiking I’ve ever done. On top of that, it poured so much that at one point we were hiking up a mountain and not entirely sure if we were on the trail or in the stream that descended beside it. When it wasn’t raining, the mosquitoes were on the hunt and particularly targeted Caroline. She wore DEET repellent and a head net—and they didn’t help much.

“Dad!” she exclaimed excitedly as we passed Elk Lake. “I just counted—I have 49 mosquito bites on my forehead alone!”

That moment reflected two nice things about hiking with Tumbler. First, mosquitoes loved her so much that they didn’t bother me as long as she was nearby. Second, she was talented at finding silver linings—like setting a new P.R. for mosquito bites.

Despite the bugs, rain, and snow, we were hooked.

Dad’s like: “Oh, you have 49 bites? That’s weird. Even though I haven’t put on repellent I don’t seem to have any. But I did scratch my leg once a couple of days ago, so I can relate.”

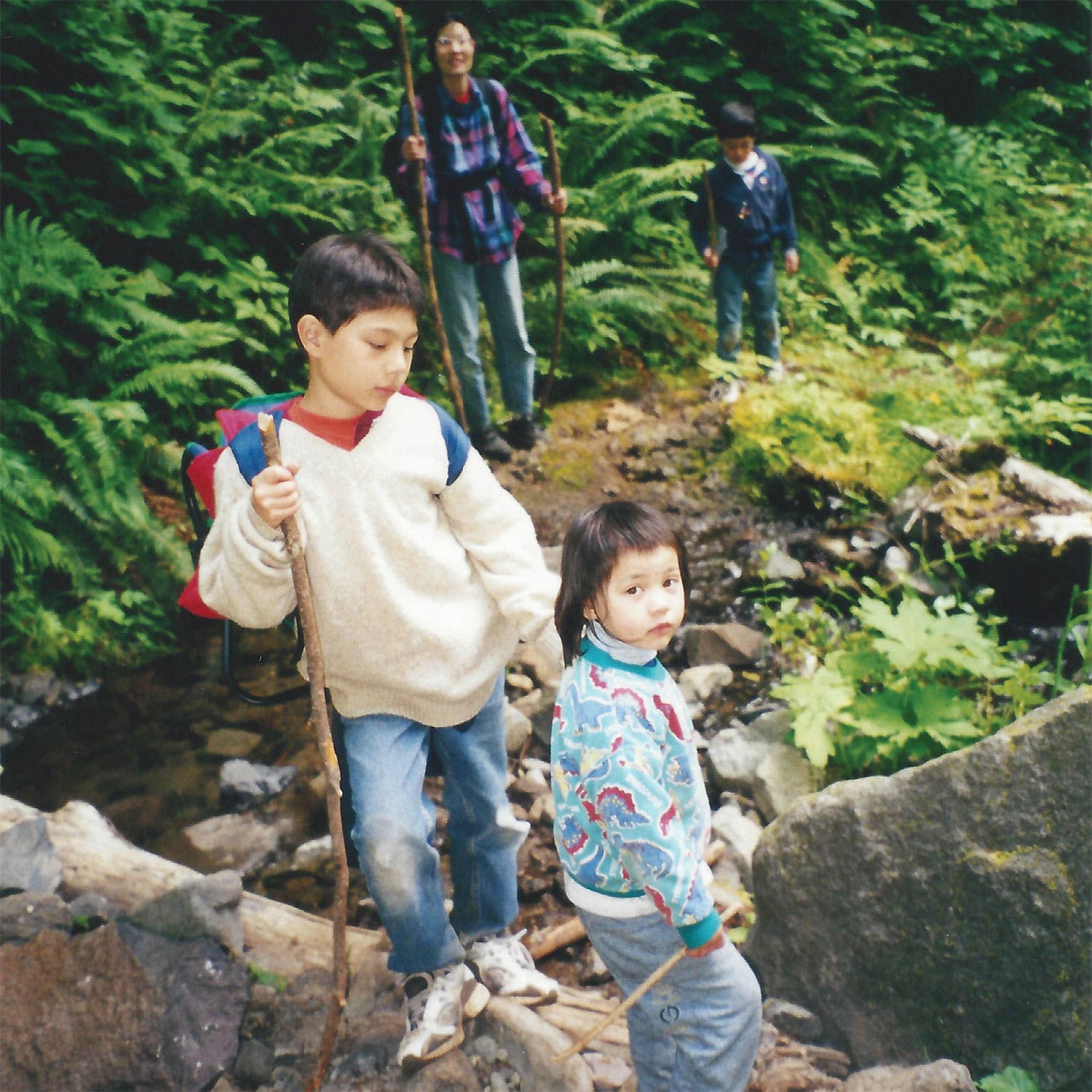

Caroline on her mom’s back on her first overnight trek at age 1.

With her brother Gregory on Oregon’s Eagle Creek Trail

Backpacking around Mt. Hood with her dad and her brother Geoffrey

Nick and Caroline circumnavigated Mt. Hood, Oregon, in 2007, when Caroline was 9 years old.

Caroline and Nick in the Three Sisters Wilderness, also in Oregon.

Nick in the High Sierra in 2016

Mosquito defense in Oregon’s Three Sisters Wilderness

Father and daughter hit the 1,600-mile mark—as measured from the Mexican border going north—on the their final section hike in 2018.

Nick and Caroline reached the PCT’s northern terminus in 2014, then spent four more years knocking off the California section.

Caroline at the PCT trail register on the Oregon/California border at age 16.

Caroline on the PCT at age 14, in the Goat Rocks Wilderness, Washington

The pair’s PCT odyssey ended at the California/Oregon border in 2018, when Caroline was 20.

Early on in our hiking partnership, I was the insufferable sage, taking advantage of my half-century of hiking experience to guide my youthful apprentice. Part of my calculation was that I could win street credibility in the wilderness that would carry over to daily life and my warnings about, say, alcohol-fueled parties.

I won’t say if this was a successful strategy.

When we were lost in the snow, I instructed Tumbler to look for blazes and old footprints. At one point, I triumphantly showed her some tracks ahead, and we eagerly followed them, thrilled that we had found the trail again. Sometime later, Caroline noticed that the footprints had toes. And claws.

“Dad,” she said, “I think that’s a bear you’re following.”

My most important wisdom concerned the weather. Nothing is more critical, I advised Caroline, than being prepared for the elements. Not only that, you must be ready for the worst rainstorm, the deepest snowfall, the coldest freeze. And above all, never let your sleeping bag get wet! We preferred to cowboy camp under the stars, so our evening ritual was to gaze at the sky and calculate whether it might rain. If precipitation looked imminent, we would pitch the tarp.

A tarp is not just a shelter; it is an art medium. I showed Caroline how to pitch it between trees or with hiking poles, how to angle it to protect from driving rain or snow, the paramount importance of “taut,” the cardinal sin of “sag.”

Once, in our first year or so, we were hiking on a forested ridge in the Oregon Cascades, towering firs all around us, when we found a small bare patch to camp on. It was a chilly, breezy evening, a bit overcast, but I assessed what I could see of the sky and pronounced us safe without the tarp.

“Are you sure it’s not going to rain, Dad?” Tumbler asked. Surprised by this challenge to my authority, I pointed out that the wind was coming from the west, where the sky looked clear. She said nothing.

Unlike some people, I wasn’t going to pretend I could predict weather by getting a glimpse of the cloud cover and “feeling” the wind.

Nothing, that is, until 3 a.m., when she shook me. “Dad, it’s raining,” she said.

Grrrr. I jumped out of my sleeping bag, grabbed my headlamp, and scrambled to set up the tarp by myself in the pelting rain. I didn’t have the heart to ask Tumbler to join me. Her contribution was to note sleepily that it wasn’t quite taut.

We finished up Oregon and Washington over three years. At that point, our motivation got a serious boost: We’ve hiked two out of three states. California, here we come! So in 2015 we set off from the Mexican border, winding north through the desert.

It was 140 miles into our first California desert hike that I saw Caroline disappearing into the gloaming and shouted ahead for her to slow down and wait. Just as I was working out how to break the news to my wife about Caroline being eaten by a cougar while tending her rattlesnake bite, I rounded a bend—and there she was.

Tumbler had set up camp, laying out the ground sheet and unfurling her sleeping bag, in a lovely sandy cove 30 feet off the trail. Boulders shielded the spot from the wind, and the sand looked soft and inviting. She was lying on her sleeping bag, doctoring her toes and waiting for me.

I looked around for something to complain about. In our hikes, I was usually the one to choose a good campsite. Alas, the spot looked annoyingly perfect. Quiet, aching, my pride as battered as my knees, I glumly complimented her on the site and rolled out my sleeping bag.

Dad’s idea of “a good campsite” doesn’t always align with mine. Dad will point to a vaguely level site dotted with rocks and elk feces and exclaim, “Caroline, this is perfect. All those weeds and roots will serve as nature’s mattress.” I relent, and then Dad whips out the air mattress he needs for his “sensitive back,” even though I couldn’t bring extra underwear because we’re “ultralight.” I have a fun night being jabbed by sticks and dad wakes up perfectly rested from “nature’s mattress.”

Caroline was now 17, and there was upheaval in our hiking relationship. Far from being empty, her pack was now about as heavy as mine, even though she is shorter and lighter than I am.

Which means that as a percentage of our body weights, I’m carrying 50 percent more than my dad. But who’s counting?

We each carried our own food, clothing, and water now. She carried the groundsheet, and I carried our medical and repair kits, water filter, and maps. When Caroline grabbed the tarp, too, I only thought about protesting.

Traditionally, I had mostly hiked in the lead, with Tumbler behind me, partly because I had hiked more quickly and could nag/coax/model a faster pace. Now everything was upended. Caroline often led, and she periodically zoomed off, especially on a downgrade, deriding me affectionately as “one-speed old dad” as she hurtled into the horizon.

Since I no longer set the pace, my own hiking idiosyncrasies began to show. I tend to hike more slowly than many other hikers but for longer hours and at a consistent pace. Tortoise-like, I prefer to get up at dawn and hike until dark, tottering slowly but with few stops and covering 28 to 30 miles a day. This made little sense to Caroline, who was now inclined to get up later and then hike faster.

I thought this dawn-to-dusk schedule was what every hiker did—I realized much later that it was just us and the freaks who attempt to break speed records.

Still, we relished these father-daughter days, even if we each contended that the other was a bit crazy. Normally at home, I’m on email and cell phone, and Caroline is buried in her phone, but the wilderness imposed quality time on us and cemented a powerful bond. Like all backpackers, we treasured the benefits of unplugging, the glorious scenery, the sense of accomplishment that comes from seeing a crag far in the distance in the morning, rounding it in the afternoon, and seeing it far behind in the evening.

Is he suggesting my phone use is less important than his?

We shared the blisters and dry stretches, the aches and the apprehensions of river crossings—oh, and the rattlesnakes. Our first rattlesnake made itself known as Caroline was returning from a bathroom break; it rattled indignantly as she was about to step on it. Later on, I was puzzling over a strange sound when I suddenly realized that it was a rattlesnake beside my foot; my contorted leap managed to break my trekking pole.

The rattlesnakes brought us together. So did the sunsets, the glacier-fed mountain streams, and the exhilaration of sliding down snowfields from Forester Pass, the 13,100-foot high point of the trail. There was a thrilling sense of accomplishment in fording snow-swollen rivers or in scoring our first 30-mile day together, and something of a spiritual reverence in passing through alpine meadows or seeing a herd of mountain goats.

Our bond deepened as the years passed and I became increasingly reliant on Tumbler. If I was in denial about our role reversal, it became abundantly clear one day in year five of our project. We were in the High Sierras, which were full of snow when we passed through in early July. It was bright and sunny, but my sunglasses didn’t fit well, so I didn’t use them.

Muir Pass was gorgeous, with a gentle slope, a blanket of snow, a stone mountaineers’ hut, and peaks as far as the eye could see, speckled with alpine lakes. We stopped at the hut to take a couple of photos, absorb the majesty of the scenery, and have a bite to eat. Then as we began to descend, both my eyes abruptly exploded with fiery pain. It felt as if grit were in my corneas, no matter how often I bathed them with snowmelt. There was some relief when I closed my eyes, but that didn’t help my hiking.

I realized immediately that I had snow blindness—basically a sunburn of the corneas—because of my failure to wear sunglasses. Cooling my eyes with snow temporarily relieved the fire but didn’t help me see, and in the process of repeatedly bending over to grab handfuls of snow I somehow lost my main water bottle from an outside pocket of my pack.

As I staggered down from Muir Pass, pained, frustrated, slow, and blind, I was almost completely dependent on Tumbler. She wasn’t just guiding me down the trail; she was now the team leader. Which made me wonder: What was I?

I could make fun of dad’s rookie mistake here, but it was kind of cool to feel like a seeing eye dog.

I had worried that Caroline would lose interest in the trail as she grew older, leaving me without a hiking partner. Instead, the opposite happened. She grew more interested, leaving me without a hiking partner. Let me explain.

After graduating from high school in 2015, Caroline decided to take a gap year before college, and after a weeklong hike together in May, she insisted on continuing on her own for another month.

Disaster!

My mom was thrilled with the idea of me alone with the rattlesnakes.

On her second day by herself, Caroline joined a “trail family” of thru-hikers—and they quickly sabotaged all my years of careful indoctrination. I’m a believer in packing ultralight, so we don’t even carry a stove. Likewise, given that my constraint is usually time away from work, we never take zero days and spend little time in trail towns hanging out with other hikers.

Alas, Tumbler discovered what she was missing. “Child abuse” is how she dryly termed my previous approach to hiking.

“Who knew?” she explained. “Hiking can be fun.”

Ouch.

On the phone from the trail that summer, she recounted with excitement that one of her new hiking buddies carried baby wipes and let her use them each evening to clean up after a day on the trail.

“What!” I sputtered. “Think of the weight!”

“Dad! They’re wipes—they weigh nothing!”

Tumbler returned from the trail proposing the heresy of carrying a stove. I argued that this was impractical: As section hikers, we often had to fly to get to the trail, and you can’t carry stove fuel on a plane.

She relented. A close call.

Almost all thru-hikers fly to the trailhead as well, but they discovered this neat trick where you go to a store after landing and buy fuel! Still, I wasn’t driving, so I let it go.

On our next hike, the insidious effect of Tumbler’s experience hiking with others became even more evident. She suggested that a half day in a trail town, to get a shower and a nice meal, might not ruin our hike. She argued that occasionally setting up camp in the late afternoon to cherish a sunset, rather than frantically looking for a camp spot as night fell, might not be evidence of insanity.

I gritted my teeth. I understood the sense of shocked betrayal felt by any dictator faced with an insurrection. I tried explaining again how much fun it is to hike for 14 hours while eating only protein bars; I patiently outlined the moral superiority to be gained by stoically enduring foil packs of cold tuna for seven days in a row even as weaker creatures slink off the trail to enjoy a hotel shower and hot restaurant meal.

Horrifyingly, I’m actually the one who introduced Dad to these tuna packets, so he could switch off between tuna and his cardboard chocolate protein bars for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and every snack in between. Worse: This is not far from how he eats at home.

My logic failed to sway Tumbler.

So our backpacking style evolved. Caroline brought baby wipes, and I generously didn’t object when she handed me half of one at the end of a hard day. We dropped into trail towns a bit more, especially when my wife or the boys joined us for a segment. (My wife, Sheryl WuDunn, trail name Blueberry, enjoys backpacking but believes in showers every two or three days.)

Giving my dad baby wipes at the end of the day was often a greater service to me than it was to him.

This evolution of our hiking pattern was bittersweet. I was thrilled to see that Tumbler’s love for hiking continued as she moved into adulthood, and I could daydream about grandchildren being introduced to the trail someday. But hot meals? Really?

Our trail transition encompassed all of the complicated feelings parents invariably have—pride, dismay, bewilderment, helplessness—as they lose control over a child journeying toward independence, making a few mistakes along the way. Sometimes the mistake is an unfortunate boyfriend or girlfriend, or a dead-end job. Sometimes it’s just a baby wipe.

In August 2018 we set off on the final leg of our PCT odyssey, traversing the northernmost part of the trail’s California section. I had caught up with the miles that Tumbler had completed on her own, sometimes on hikes with Blueberry but mostly alone. And while I used to love my solo hikes, now I found they were marred by how much I missed Tumbler, both in the she’s-not-here way and in the she’s-growing-up way.

For our last 200 miles, from the little town of Castella to the Oregon border, we had fine weather, and the tarp stayed at the bottom of the pack. But forest fire smoke blanketed the trail, obscuring scenery like the jutting crags of the Trinity Alps and offering a reminder of a changing climate and environment. When I began backpacking in the 1960s and 1970s, trails were rarely closed because of forest fires, while now this happens all the time.

As we hiked through the Russian Wilderness, past the strange natural stone formation known as The Statue (it looks like a huge Trojan Horse on a cliff), we reflected on the continuity and change in the wilderness and in the hikers who pass through it. The geography hadn’t changed much in 1,000 years, but we had been transformed in just seven.

It was late in the season for thru-hikers, so the PCT was mostly empty. One day we didn’t see any other hikers at all. We talked—about music and politics, friends and history and books.

I had hiked a part of this segment, north of Seiad Valley, as a 15-year-old high school student with a 76-pound pack. I shared with Caroline memories of that old trip and of my high school days; she expressed a polite interest in this medieval history.

As we chatted, we disturbed a pine marten on the trail ahead of us—the first I had ever seen. It ran off into the woods, and we talked about the animals we had seen on the PCT: two bears, one cougar, one fisher, one lynx, and 14 rattlesnakes. We had also worn out about five pairs of shoes each and lost countless toenails.

Fun fact: I once found a pair of decent shoes in a hiker box and used them for about a month. It’s fun to tell people that I’ve literally walked in someone else’s shoes for 500 miles. Also, let’s be clear: My dad is the one who loses toenails, not me!

We had managed this joint project together, seeing so much wilderness, enduring so much cold and rain, feeling so much exhilaration and awe. She had grown from a little girl incapable of carrying even an empty pack into a capable outdoorswoman, either because of me or in spite of me. As we completed the last few miles of our seven-year section hike, it hit me that just when you think you’ve figured your kid out, it’s time to let go. I wanted to savor the memories and chat about all our adventures together—but then I buckled down, because I saw that Tumbler was waiting for “one-speed old dad” to catch up.

I wanted to finish as we started: one step at a time, side by side.

And the most gratifying part of that last section? We spent a good deal of it talking about what to hike next, together.

Nicholas Kristof is a columnist for The New York Times and winner of two Pulitzer Prizes. His next book, Tightrope, will be published in January. Caroline Kristof, his daughter, is a senior at Harvard.

Why Section Hiking?

Doing a long trail in chunks has obvious advantages over thru-hiking—it’s easier on families and jobs—but it has other benefits, too.

Conditions If you’re flexible with the route, you can hike sections during optimal times. In early May, perfect desert hiking season, we would sometimes do a week or so in the Southern California desert. In July or August, we would do a week in the mountains.

Crowd control We were able to time sections so as to avoid the PCT equivalent of rush hour, when thru-hikers are everywhere.

Recovery Most blisters or shin splints can be endured for a week or two if you know that afterward you’ll have a couple months of rest.

Scenery It’s the same terrain thru-hikers see, but it’s difficult to get blasé about radiant beauty when you’re exposed to it in brief bursts.

Logistics There’s no real advantage here, as getting on and off the trail is a challenge all hikers have to figure out. We sometimes found friends to take us to a trailhead, or we took buses, trains, Ubers or taxis, or we caught rides from trail angels, and of course we hitchhiked as well. Logistics are much easier on the Appalachian Trail and harder on the Continental Divide Trail.

Trail angels These heroes are an American treasure, and although I was originally shy about accepting their help—figuring their aid should be reserved for thru-hikers—we did rely on them several times, and they were a fantastic part of the trail experience.

Community One disadvantage of section hiking is that you miss the camaraderie of getting to know and grow with the same hiking pals over five or so months. On the other hand, section hikers stretch out the magic of a long trail over a number of years, meeting hikers and making friends across several “classes.”