10 Questions Thru-Hikers Hate Answering

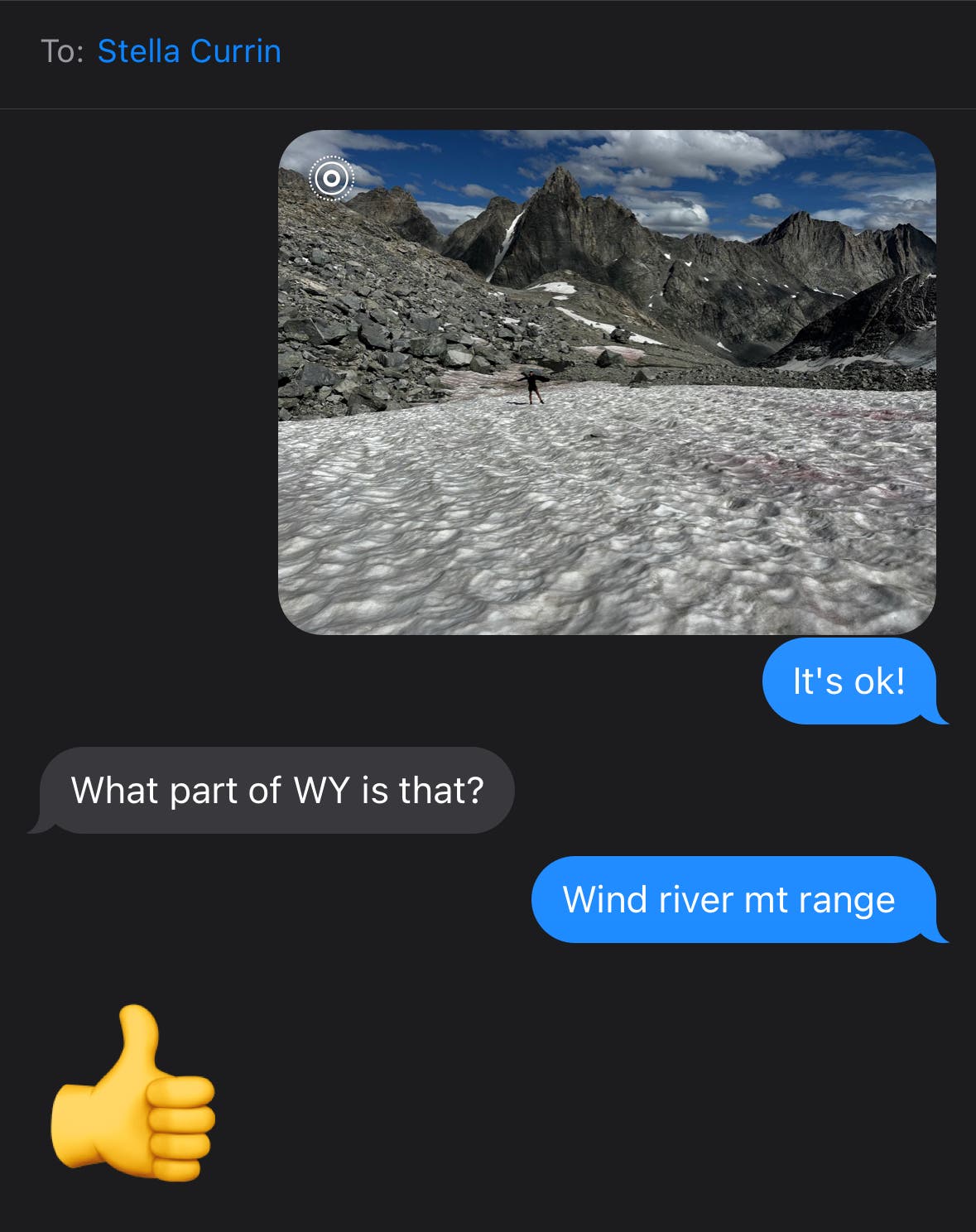

Count it! (Photo: Grayson Haver Currin)

A few days ago, I asked my wife, Tina, to rattle off the most common questions she’s heard in more than 11,000 miles on trail. Just minutes earlier, I had written down the first seven queries that came to my mind. Without any hints or urging, she named the exact same seven questions, with the exact same verbiage, in almost the exact order. That is how frequently thru-hikers hear the same set of frequently asked questions—where do you get your water, food, money, and so on.

We also hear these questions so often that we—or I, at least—begin to daydream about sarcastic responses, answers so cynical or reductive or stinging that they could almost be true. Over the years, I have collectively passed hundreds of miles conjuring my hypothetical ripostes, giggling at my own jokes as I make my way up a trail.

It has comforted and humored me, then, to learn that other hikers do the same. I’ve spent many days at diners in trailside towns and nights at lean-tos laughing with other hikers about what we should have said when a dayhiker asked the same old question earlier that afternoon. Maybe it’s rude, but it’s also a safeguard against the insanity that thru-hiking’s tedium can bring.

As the start of thru-hiking season arrives, I’ve compiled the 10 most common questions that we hikers get, plus my favorite sarcastic response to each. I’ve also added some honest answers: All snark aside, we thru-hikers have an opportunity to help break down the barriers that keep people inside. Why not use it?

Question: Where do you get your water?

How I Want to Answer: I carry it. A few decades ago, NASA invented dehydrated water for space exploration, and it’s so light that it weighs practically nothing, as if it’s nonexistent. To drink it, all you need to do is rehydrate it—with water, from a stream or lake or even a mud puddle.

What to Consider: This is the question that bums me out, because it illustrates how much we’ve separated ourselves from the world that keeps us alive. Water just comes out of faucets and bottles and cans and glasses, right? More than once, while explaining that hikers simply drink out of creeks and rivers and springs and lakes and the occasional trailside spigot, I’ve seen people’s eyes widen with an epiphany, as if they are relearning that the water they drink at home first comes from somewhere in the wild. I tell people about the wondrous advancements of water filters and how, if you treat it well, a Sawyer Squeeze can keep you hydrated for a very long time. Maybe next time, they show up with that, not a bag full of disposable bottles.

Question: Do you carry all of your food the whole time?

How I Want to Answer: Honestly, what I can’t carry I kill or steal. I stuff every available corner of this 55-liter Hyperlite backpack with as much food as I can manage at the start of a hike, but that lasts maybe a week. And then I’m either trapping small game or playing a small game with day-hikers like you. I wait until you put your pack down and then pilfer every protein bar you have. Hey, have you ever seen Yellowjackets?

What to Consider: This is an opportunity not only to remind people that the distance between hiking trails and small towns or even legitimate cities is often not that great, but also to introduce the concept of trail magic. I have walked 100 feet off trail into a town to buy groceries for the next several days, and I have hitchhiked more than 100 miles into a town to do the same. The former is easy, while the latter takes patience, commitment, and trust in absolute strangers. I tell people that we go into a town every few days to rest, eat, and resupply, so that we rarely have more than a week’s worth of food strapped to our backs. And if the time for an exit is near, I tell them that, if they give us a ride, they will have performed their first act of trail magic. This works almost every time.

Question: Do you get scared?

How I Want to Answer: <takes long drag off a joint rolled in birch bark found on trail> Yeah, man, but doesn’t everyone? Climate change, the international rise of strongmen, the United States’ failing social safety network, wars, famine, disease, pandemics, the inevitability of death—it’s a wonder people still bring kids into this world, you know? Aren’t you scared, bro?

What to Consider: Actually, what’s above is entirely true. The world off trail is pretty scary for a lot of reasons, no matter your political persuasion or your relative trust in science and/or God. But the trail itself is rarely scary. True, I was three miles away from a murder scene on the Appalachian Trail in 2019, and Tina and I once sprinted down a highway in the dark to escape the wrath of a true-to-life Florida Man on the Florida Trail. But moving from one blaze to another, the world becomes a kind of cocoon, the decision about what is next already made. I rarely feel more at home than when tucked into a tent under a tree. I tell people this, and they don’t believe me. But they go home and lock the doors I don’t have.

Question: Do you ever see bears or snakes or wolves or mountain lions or alligators or any other beast that could kill you?

How I Want to Answer: In the past, yes, that happened. But a few years ago, thru-hikers unionized and pooled our resources to hire a massive team of wilderness tamers who march up and down the trail every day of the year, capturing any wild beast they see and taking it to the zoo at Bear Mountain State Park in New York. Have you seen any beasts on your walk today? No? You’re welcome.

What to Consider: This is the same question as above, simply in a different form. Its essence is “Do you get scared?” And while the danger from any of these animals is obviously real, part of the continuing thrill of thru-hiking is having and then navigating inevitable encounters with things that could kill you. A Florida panther can be a fearsome hang, but seeing one of the 120 or so that remain in the wild is a highlight of my life, despite a split second of panic. The same is true for grizzly bears in Wyoming and Montana and even one particularly vicious cottonmouth in Florida, which rose from its coil to hiss its warning like a goddamn dragon. I tell people that the hope is to see some of these animals and to have the sense, skill, and luck to stay out of their way. That’s part of the adventure.

Question: What does your family think?

How I Want to Answer: I’m out here walking 3,000 miles in sneakers, wearing a stinking backpack and hitchhiking into small mountain towns with absolute strangers. It is safe to assume that my relationship with my family sucks and that I am running away from that problem, albeit very slowly.

What to Consider: When I am home, I work a lot, whether shuttling across the country to interview assorted musicians or squirreling away in my office to turn those experiences into words. I am not proud of this, but, while doing that, I have a tendency to shut out some of the world, to focus so much on work that I forget about the rest of life. (More on this with the next question.) But on trail, away from daily deadlines and calls, the time I fill with quotidian tasks back home opens up, and I start to call friends and family members, simply to catch up and hear about their lives and worlds. I tell people that my family has accepted that hiking is part of a lifestyle that makes me feel whole and that they even like it when I hike, because it means I’ll probably start calling.

Question: How do you pay for something like this?

How I Want to Answer: A: I don’t. George Soros does. B: I’m a man of wealth and taste. C: Bitcoin—ever heard of it? D: I don’t like to talk about my trust fund with strangers. E: When I was 18, I married an octogenarian for money, and now she’s dead. Anything else you want to know about my good choices?

What to Consider: Disappearing into the woods for six months at a time will forever be a luxury and a privilege. Any hiker who tells you otherwise, despite the material conditions of the rest of their lives, is a liar. That doesn’t mean that doing so comes without sacrifices, at least for most of us. My wife, Tina, and I work very hard when we’re off trail, setting aside money so that we can afford to live in the woods. We don’t have kids for a lot of reasons, including the ability to do just that. And our house and belongings are well within our means, so that mortgages and car payments do not dangle above us like the Sword of Damocles while we walk. I tell people that there are surely carefree thru-hikers with trust funds, but that, for most of us, we make difficult decisions about the rest of our lives so we can continue to do this.

Question: Do you get tired?

How I Want to Answer: Only of that question, really.

What to Consider: One of my favorite aspects of thru-hiking is how exhausted I feel at the end of each day, like I have poured every ounce of energy I have into the effort and now I need to eat and sleep and prepare myself to do it again. That can sound masochistic to the uninitiated, but I do think it speaks to how little we can get by with using our bodies in day-to-day life. I tell people that I rarely get more fatigued than I do when I’m on a long trail, and that it is a wonderful reminder of just how much our bodies can do.

Question: Where do you sleep?

How I Want to Answer: I have a bed frame in my backpack. Crazy, right? I make the mattress anew out of leaves every night.

What to Consider: I actually understand this question entirely. Less than a decade ago, I was not a camper, let alone a thru-hiker who carried a tent for thousands of miles at a time. Camping for one night, maybe two, seems logical and fun. Doing it for weeks on end can seem … daunting, terrible, impossible? I tell people that there’s nothing magical about how or when we sleep: Around dusk, we set up our tent or unfurl a ground cloth, talk until we fall asleep, and wake sometime before dawn to start walking again. And sometimes, we even get a room in a hotel or a bed in a hostel, just like anyone else on so-called vacation. As with most of this stuff, it’s a simple idea that, when explained, opens folks’ minds to new ways of living.

Question: Do you ever smell bad?

How I Want to Answer: All the time. Right now. In fact, I can smell your laundry detergent from here, and all I can think about at this moment is how I want to go home with you, take off my clothes, and climb into your big steam shower. Wait, that sounded wrong, didn’t it?

What to Consider: I love showers so much that it’s a punchline at our house. Tina loves to tell absolute strangers how many showers I take a day (not telling!), and I sometimes shower simply because I’m bored. But my level of filth on trail is also a punchline, how the grime seems to cake to my legs and face and backpack more than most anyone else we encounter. I enjoy the opposites, moving between them in different phases of my year and life. I tell people that, yes, I stink often, but that I try to revel in it, too, to recognize that this is a new way to live for a little while, so different than the domesticated me back home.

Question: When will you finish?

How I Want to Answer: Before I am dead, or at least I hope so.

What to Consider: Late last year, I had a work-imposed deadline for finishing a trail. It was the least I’ve ever enjoyed a thru-hike, not only because it meant that I had to walk a lot with very little rest but also because it seemed to comport with the rest of the world’s idea of time. You set a schedule, and you deliver. But on trail, you cede such a large measure of control—of the weather, of the terrain, of your body—that sticking to a strict timeline becomes an injury-inducing fool’s errand. I tell people that I have an idea of when I might finish and that I’ll be happy to do so, but that finishing with my sanity and health is more important than a due date.