Thoreau Slept Here: The Thoreau-Wabanaki Trail

'West Branch Penobscot River'

West Branch Penobscot River

Ray Reitze prepares breakfast on Umbazooksus Stream

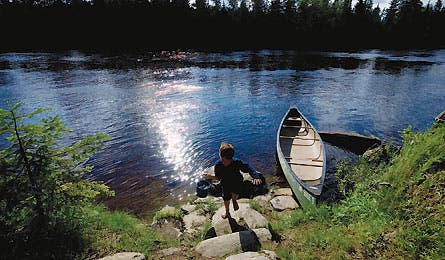

The author’s son running up from West Branch Penobscot

Charlie Clynes new the Canvas Dam Campsite

“We struck it lucky,” Ray said, echoing my thoughts. This July night had it all: a half-moon shimmering over misty water, steady breezes to keep bugs away, laughing loons, and plenty of good, witty company.

It was our final night on the West Branch of the Penobscot River, which runs through upper Maine northwest of Bangor. We had spent four days paddling in the wake of America’s first great naturalist writer, Henry David Thoreau, and his Penobscot Indian guides. Our journey was a small part of the recently inaugurated Thoreau-Wabanaki Trail, a network of paddling and hiking routes through what was then–and still is–New England’s largest expanse of wilderness. The 200-mile path forms a rough circle from Bangor to the northern border of Baxter State Park.

Thoreau journeyed to northern Maine several times in the mid 1800s, traveling with friends and relatives, river men, and Native American guides. He talked and wrote often of the “numerous forest-clad islands, extending beyond our sight both north and south, and the boundless forest undulating away from its shores on every side, as densely packed as a rye-field, and enveloping nameless mountains in succession.”

Though the forests are no longer uninterrupted, most of Thoreau’s descriptions hold true. This has to be one of the few places in New England where you can read an account of a place written 150 years ago and know exactly where you are.

The series of essays, lectures, and magazine stories that resulted from Thoreau’s travels in Maine were collected in The Maine

Woods, published posthumously in 1864. It would take nearly 150 years before Thoreau’s routes would be stitched together into the Thoreau-Wabanaki Trail by a nonprofit called Maine Woods Forever, which is dedicated to protecting the legacy of the largest officially uninhabited area in the Lower 48–some 10 million acres of rivers, lakes, ponds, hills, and mountains.

Our 30-mile paddle would take us from Hannibal’s Crossing, just downstream of Moosehead Lake on the West Branch Penobscot, to Umbazooksus Lake. Our group of 11 included Maine outdoor educators Ray and Nancy Reitze and photographer Bridget Besaw. And I had brought along my son Charlie in celebration of his fifth birthday. The trip would be Charlie’s first deep exploration of the northern wilderness.

The upper West Branch is an intimate, narrow path of river cradled by thick forests. Thoreau descended this section twice, in 1853 and 1857.

We paddled past Thoreau Island (called Warren Island in Henry’s day), where the author camped. We glided by a stream he fished, and another he ascended in hopes of sighting a moose. Thoreau was interested, more than anything, in seeing moose, which looked, to him, like “great frightened rabbits, with their long ears and half-inquisitive half-frightened looks.” He searched many of the West Branch’s tributaries, such as Moosehorn Stream, usually returning to the main waterway frustrated. But within an hour of launching we had caught sight of a moose cow splashing in the river.

We paddled to the beats of chattering kingfishers, rasping mergansers, and tail-slapping beavers, whose dams held back ponds at river’s edge, a forested backdrop speckled with red and yellow flowers.

A few puffs of cumuli added character to an otherwise seamless sky, reflecting off the water. It seemed unlikely, as we glided down the river, that a more brilliant day had ever stretched across the bow of a canoe.

We had chosen the West Branch for its remoteness and because it is largely flat water with no portaging–a perfect pick for a five-year-old’s first multiday canoe trip. With the river running reasonably high, we could make good speed without working up a sweat, though Charlie quickly learned to enjoy challenging lily dippers with spirited calls to “throttle up!”

In Thoreau’s day, Pine Stream Falls was wild enough that he chose to get out and walk around it. Now, the whitewater is gone, thanks to Chesuncook Dam, completed in 1904, but a mile or so of Class I quickwater was enough to give little Charlie a thrill.

The waterway slowed and widened as we approached the convergence of the West Branch, Umbazooksus, and Caucomgomoc streams. The meadowy junction that had been called Chesuncook–”a place where many streams empty in”–is now Chesuncook Lake. Here, the river’s intimacy opens into a chaos of lakes, valleys, and mountains. Towering above it all is Mt. Katahdin, the 5,267-foot “cloud-factory” Thoreau tried to climb, unsuccessfully.

Pulling 12-foot-long sticks of ash from the canoe, we poled our way into the Caucomgomoc’s slow-flowing waters, past Thoreau’s camp of July 26, 1857. We continued up the inlet, past rocks still adorned with pins and rings that supported giant “boom chains” that once held back millions of logs waiting to float to sawmills downstream.

Even in 1857, Thoreau was disturbed by the battalions of loggers moving into the north woods, whacking down trees and building dams to bring up water levels so that logs could be floated to mills downriver. The men inundated forests, he wrote, “without asking Nature’s leave.”

As we approached the Canvas Dam campsite, sending a pair of mergansers into flight, the outside world seemed very far away. Above the shore, white pines swayed in the wind, backed by tremendous stretches of forest.

Thoreau chose to travel with Native Americans to deepen his understanding of this environment. On one trip, he made a pact with Penobscot guide Joe Polis–”Indian Joe”–that each would tell the other all he knew. Our journey’s leader, Ray, was also influenced by a Native American named Joe. In fact, he spent most of the first 18 years of his life under the tutelage of a Micmac elder he called Grandfather Joe, who taught him about wild edibles, hunting, and trapping.

As soon as we arrived at the Canvas Dam campsite, Ray displayed the skills he’d learned, combing the surroundings for sarsaparilla and chaga, also known as tinder mushroom, a birch-loving fungus whose burnt-charcoal appearance belies its mellow and flavorful taste. Soon, he returned with handfuls of both.

“And if anyone gets sick, I’ll boil up some pine needles,” Ray said. “A cup of pine-needle tea has more vitamin C than a cup of orange juice.”

Rising early the next morning, I read a passage from Thoreau (how can you not?) that could describe our setting 150 years later: “Cold morning. Silk veils of mist rising from the lake. Mergansers swimming. Light strikes the mountain first, coloring its green slate-gray. Hills beneath are black. Sky beyond, pure azure. A cloud rests on the pinnacle’s west end, a white ribbon pausing on its passage in the wind.”

After breakfast (wood-smoky pancakes with local maple syrup), some of us leaped into the tannin-tinted water to wash the last cobwebs from our heads. Upriver, a big bull moose had the same idea; he splashed in the shallows on the opposite shore while, overhead, a lone eagle circled and dived for his breakfast. Then we made the short paddle to Langley Creek campsite, our last of the trip. From our vantage point a couple of miles across the lake, we could see Chesuncook Village, which Thoreau knew as Ansel Smith’s logging camp.

Accessible only by floatplane, boat, or four-mile hike, the “village”–just a cluster of camps and cottages–has a general store that’s famous for its homemade root beer. We had planned to make an after-supper run, but then the loons started calling.

It’s hard to find a lakeside campsite in these parts where you won’t hear at least one loon. Joe Polis told Thoreau that yodeling loons predict an approaching wind–and, sure enough, an offshore breeze began to build in late afternoon, postponing our side trip to the village.

Without taking its customary sunset break, the wind blew hard all night, and by morning it had worked the lake into a froth. With a headwind coming at us directly off Chesuncook Village, it would be almost impossible to paddle there in a canoe.

“Oh well,” Ray muttered. “Would you believe me if I said Chesuncook Village is more interesting to read about than to visit?”

But we still had to get to our take-out. Standing on the shore and studying the map, we soon worked out a plan. We would sneak along shore, hiding in the lee of several small islands, then make a crosswind dash for the entrance to Umbazooksus Lake.

Once we launched, the wind proved quite manageable, so we decided to quarter through the swells and into the middle of the lake. We caught a hard crosswind off Moose Pond, then curved around to put the wind at our backs. From there, we raced down the middle of the lake, tearing into the take-out at Umbazooksus Lake.

At the end of his “Chesuncook” essay, Thoreau arrived at an idea that was as yet unheard of in America: setting aside wild lands “not for idle sport or food, but for inspiration and our own true recreation.” Although the conservationist movement inspired by Thoreau has often been outflanked and outfought, it has managed to preserve for America many of its most valued treasures.

On our final night, we waited until Charlie was asleep before we talked of the bitter struggle in northern Maine between developers and loggers and environmentalists. Certainly, I hoped to pass along an ethic of environmental stewardship to my own children. But that would come later. For as environmental educator David Sobel has written, “Let’s first teach our children to love the outdoors, before we ask them to save it.”

Our campsite that night seemed like a good place for a life-long love of the wilderness to take root. Before turning in, I went for a final swim, then reclined against a warm rock, watching the half moon rise over the mountains. A low mist formed atop the lake, filtering the last of the orange light from the west. Finally, I joined my son in the tent and drifted into sleep with an extraordinary feeling of privilege, my mind rinsed by the sound of lapping water and wind in the trees.

“We’re paddling in heaven,” Ray had said earlier that day. “The world just doesn’t know it, though they’re looking for it every day.”

PLAN IT | Thoreau-Wabanaki Trail, ME

When To Go

The months from July through October offer the perfect combination of stable weather and declining insect hordes. Summertime brings highs in the 70s and lows in the 50s.

Gear

Pack your gear in a drybag like the NRS 3.8 Heavy Duty Bill’s Bag ($80, nrsweb.com); it has shoulder straps for portages and is so bomber it should last a lifetime. Pack bug spray with DEET (we like 3M’s Ultrathon lotion: $6, rei.com) and a headnet just in case (try Sea to Summit’s Mosquito Head Net: $8, seatosummit.com).

Map and Books Pack Quiet Water Maine: Canoe and Kayak Guide, by Alex Wilson and John Hayes ($18, Appalachian Mountain Club Books) and Northern Forest Canoe Trail Map #11 ($10, The Mountaineers Books).

Outfitter

Join a guided trip (or rent canoes and supplies) and arrange a shuttle with Northwoods Outfitters in Greenville. (866) 223-1380, maineoutfitter.com

The Way

From Millinocket, take Bates St. 0.8 mile north to Millinocket Rd., and turn left. After 7.5 miles, Millinocket Rd. becomes Golden Rd.; stay on Golden for 45.6 miles to the put-in at Hannibal’s Crossing, a bridge where Golden Rd. crosses the West Branch Penobscot River.

Contact

thoreauwabanakitrail.org