The Last Best Place

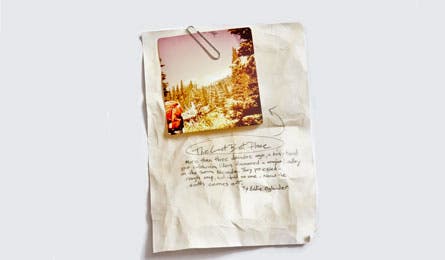

'The original article, sent to backpacker in 1983. (Julia Vandenoever)'

The original article, sent to backpacker in 1983. (Julia Vandenoever)

Restored photos show hidden peaks in the Sierras.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Hikers have long sought hidden trails, secret valleys and lush, untouched mountain meadows. A young man discovered such a place deep in California’s Sierra 35 years ago. Eight years later, in 1983, he wrote about the place and submitted it to BACKPACKER—then he disappeared. The story never ran, because we didn’t think it was true. We changed our minds after seeing this wire report.

August 20, 2010, Mammoth Lakes, Calif. (AP): United States Forest Service officials are refusing to comment on reports that a hiker recently discovered a journal buried near a stone cabin deep in Inyo National Forest, in the southern Sierra Nevada, or on speculation that the journal and cabin both belonged to John Muir, who died in 1914.

“There are lots of things buried in the mountains,” said a Forest Service official who requested anonymity, “and there are probably huts and cabins that only a handful of people have ever seen. That doesn’t mean they’re important, or anything to get excited about.”

Jim avoided the customers. He avoided smiling, too, and talking, and whistling. Jim stayed in the back of the store, behind the thick green woolen blanket he had strung from the ceiling, far from the Thinsulate and the polypropelene and all the other materials and inventions whose names, when uttered aloud, made Jim grunt and hammer whatever he was hammering with extra attention.

He was a tall man, almost 6’5”, and skinny, with a long brown beard and thinning hair and the glowing brown eyes of a madman, or a rich evangelist. He could have been 35, or 60. He wore faded jeans and work boots and a wool button-down shirt, even in the summer, and he spent the better part of every day bent over the wooden bench in the back of the store, hammering nails into a boot, or sewing up a rainfly, or straightening a tent pole. Whenever a customer came in and asked one of the employees out front if he or she might suggest a good camping spot, invariably one with “nice views and clean water, and no bears and not too far,” the hammering took on a terrible, joyless cadence and the store rang with hammer blows and Jim’s grunts, and many times the customers’ eyes widened and they scuttled hurriedly out of the store without buying anything.

Why any merchant would ever hire Jim to work within earshot or eyesight of customers was a mystery the other employees discussed often. It was the spring of 1975, and they all worked at Sierra Designs, on the corner of Alma Street and University Drive, in Palo Alto, California. They were students at Stanford University, most of them, and they did the things college students did: They traveled to Grateful Dead concerts in San Francisco; threw Frisbees in the parking lot during breaks; and they drank beer and talked about how they would never compromise themselves. At lunch, over hamburgers and milkshakes at Peninsula Creamery, just a few blocks away, they swapped theories about what had broken Jim, what had turned him into the thing in the backshop.

He had been a millionaire, one of the college kids said, but gave it all up after his wife had left him. No, another said, Jim spent his boyhood striding the Sierra, with nothing but a stick and a piece of fishing line, and he lived off the land until a woman brought him to civilization, and then to emotional ruin. No, no, no, another said. Jim grew up poor and he was still poor. He came from the hills of Kentucky and he had attended Stanford on a basketball scholarship, but his college career came to an end when he was out for one of his midnight strolls and he saw a man beating his dog and he killed the man, choked him with his own dog collar! After his six years at Folsom Prison, Jim couldn’t get hired anywhere but here. That wasn’t the real story, either, someone else said. Jim had been a brilliant mathematician at Stanford, on the verge of his Ph.D., spending hours after hours in the library, working on Fermatt’s Theorem. Then late one night, when he was gazing at a harvest moon sinking toward the foothills, then down at some equations he was scribbling, then back at the moon, something snapped. The way this particular student heard it, Jim rode his bicycle to his apartment, burned his math books and math notes, planted a garden, and had been spending weekends in the Sierra Nevada ever since. He paid for his rent and his garden and his gasoline with the money he made repairing stuff in the back of Sierra Designs.

There were as many stories about Jim as there were flavors of milkshakes at Peninsula Creamery, and just like the creamy drinks, one was as delicious as the other. None of them was exactly accurate, as it turned out, but all of them were partly true.

The college students learned something about truth that spring, and something else about the heavy burden of responsibility and the delirious and unexpected joy of running from it. They learned about consequences, too, and how the more time passes, the heavier those consequences become. We all learned something that spring.

It was an odd time, or maybe it just seems odd now, in hindsight. Maybe now, 1983, will seem odd in a few years. Maybe all times are odd. Back then, a light plane had crashed in, or near, Yosemite National Park earlier in the spring, supposedly carrying a load of marijuana. Every week or so, someone would come into Sierra Designs looking to buy a sturdy pair of hiking boots and all the topo maps he could find of the area. The employees joked about gangs of backpackers headed into the mountains, searching for the legendary and reputedly hyper-potent “Yosemite Lightning.” That definitely qualified as odd. An heiress named Hearst was calling herself “Tanya,” pulling stick-ups in San Francisco. Odd. The Vietnam War was ending and Mitchell, Ehrlichman, and Haldeman were going to jail. Werner Erhard was charging rich people hundreds of dollars to sit in hotel ballrooms and get yelled at. Would anything ever be odder than that?

And more than ever before, people were driving to trailheads, tromping into the backcountry to reconnect with something they thought they had lost. Lawyers and doctors and dentists pulled into the Sierra Designs parking lot in their Volvos and BMWs and they strode into the store and asked about beautiful waterfalls and secret campsites that weren’t too terribly far from trailheads. Though sometimes they heard the awful hammering and left.

The college kids only saw Jim come out of the back once. It was a drizzly Thursday afternoon. A slim, red-headed woman wearing sneakers and a tired frown came into the store with two boys. The oldest looked about 12, and he lurked in the store entrance, scowling, smoking Camel cigarettes, pulling up the collar on his leather jacket, and glaring at people who walked by. His little brother sniffled and wiped his nose on the sleeve of his oversized sweatshirt and stared at the floor. She wanted a school coat for her sniffling kid, but only had 15 dollars. Did the store have anything? While one of the college kids tried to figure out how to tell this woman she was in the wrong store, that 15 bucks would barely get her a ground tarp, the blanket parted and out strode Jim. He didn’t say anything to the woman. Jim sidled up to the young boy, who was studying a giant picture on the wall, a picture of a waterfall and wildflowers and big, furry marmots. The boy was tracing grimy lines on the poster with soft, dirty fingers.

Jim bent down and whispered something to the boy and the boy whispered back—the mother was still talking to one of the college kids—and Jim walked back to his bench, grabbed something flat from the bottom of a giant cardboard box filled with old boots and shoelaces and nails and bits of nylon, then returned and thrust the object into the little boy’s hands. He looked at it, then folded it and jammed it into his hip pocket. At that moment, the mother said something that caused the college kid to blush and stammer a string of apologies, and then she marched out of the store, but not before smacking the smoking, leather-jacketed kid on the back of the head and hissing at the kid by the wall to stop his daydreaming, what the hell was the matter with him anyway, was he stupid, or just slow? As she got into her side of the car, the smoking kid punched the daydreamy kid in the arm, but the little boy didn’t say anything. It looked like he was used to it.

A week later, the woman was back, and this time she marched into the store, and when one of the college kids asked if he could help her, she slapped him across the face. The manager saw it and asked what the problem was.

“The problem?” the woman asked. The problem!?!? The problem was one of his dirty, drug-addicted, hippy workers had been putting dreams in her kid’s head, and there was already something off about the boy, and now he wouldn’t shut up about the magic place, and did she look like she was someone who believed in magic?

The little kid was standing by the car, playing with a daffodil, humming. The kid with the motorcycle jacket was standing in the doorway, smoking another cigarette.

The manager said, “If you would explain what…”

She shoved a wrinkled piece of brown paper at him. There were mountains and valleys drawn on it, and rivers and waterfalls, and a skull and crossbones next to a circle of blue touching a dotted line. And at the end of a red dotted line, a few inches past the blue circle, dancing golden fish and a little stone house with smoke curling from its chimney. The smoke curled into letters that said, “Magic Lives Here.”

“Look outside,” the woman commanded, pointing past the kid in the leather jacket, at the little boy talking to his daffodil. “Does that look like someone who needs more dreams cluttering his head? Do I look like I need it?”

“But,” the manager said.

“Does that look like a child who needs another fairy tale from another man?”

“I see…” the manager said.

And did she look like she could afford to take a weekend off and go gallivanting in the hills? Did she look like some fancy housewife who could take her son away whenever he got some fancy notion about make-believe in his head? What was wrong with that idiot with the hammer and the crayons, and why was he even allowed to talk to children?

As she yelled, the manager kept glancing toward the back of the shop, behind the canvas curtain, where the sound of hammering had fallen quiet.

“I’ll take care of this right now,” the manager said, and walked back toward the curtain. And as the lady was leaving, grabbing her chain-smoking kid by the ear and dragging him to the car, one of the college kids snatched the homemade map off of the counter. At closing time, for the first time any of the college kids could remember, Jim stayed late. The students played hacky sack in the parking lot, and drank Olympia beers, and they heard Jim rummaging through drawers and slamming things around and muttering. When he came out, he cut them all looks, but they ignored him. They were planning a trip to the place where magic lived, a trip that would change their lives in ways none could have guessed.

There were three of them, all Stanford seniors, and oddly matched the way college friends often are. Betsy was a blonde, blue-eyed film major from Kansas City whom the others called Mad Dog because of her early morning, pre-caffeine crankiness and grouchy demeanor even in good times. Betsy drank her coffee black and referred to the two male students with her as “punks,” as in, “Are you punks ready to get this show on the road yet, or what?” Betsy was only 5’2”, but she scared people much bigger.

Max drove. Max was studying political science, and had announced his plans to be a millionaire by the time he was 30. Max wore button-down shirts and loafers, shaved every morning, even on weekends, and called adults “Sir” or “Ma’am.” He had brown hair and brown eyes, was a shade under six feet tall, and he never seemed to worry about anything. The three friends were riding in his Jeep, a green Cherokee that had been a high-school graduation gift from his parents.

Roger sat in the backseat. Roger had started as an English major, switched to philosophy, and ended up studying Eastern religions. He carried around a copy of Baba Ram Dass’s Be Here Now with him at all times, and lately had taken to wearing a purple silk robe that he had found at a flea market and playing his harmonica, loudly and badly, in public places. His hair, parted in the middle, hung to his shoulders. He was the same height as Max, but thick with muscle where Max was lanky. Roger had been recruited out of high school, from Corvallis, Oregon, to play point guard on the Stanford basketball team. But after a week of practice, when he told the coach to “mellow out,” the coach kicked him out of the gym, and Roger never returned.

Roger had for the past six months been spending all of his spare time, when he wasn’t working at Sierra Designs, sitting in his apartment with the lights out. “I’m thinking,” he had told Betsy and Max, when they asked why he didn’t go outside more often, or answer his phone, or ever join them for beer and burgers at The Oasis in Menlo Park. (Roger had stopped eating meat midway through his junior year.) Roger’s coworkers worried about him. His parents worried, too, ever since the previous winter break, when, back home in Corvallis, Roger had refused to say anything unless it had been written in The Hobbit or Catcher in the Rye or Be Here Now. When his parents told him he had to eat his dinner, and wondered if being a vegetarian was really such a good idea, and he started talking about dwarves and elves and how time was just a man-made construct, they made him see a psychiatrist. The doctor told Roger and his parents that he was suffering from depression, and that he needed help. But Roger said he needed to think, that it was the world that was messed up, not him. Back in school, he didn’t show up for class, and the Sierra Designs manager had to remind him to cut his fingernails, and to wash.

“Don’t be a punk,” Mad Dog had told him two weeks earlier, in his dark apartment, as the trio studied the hand-drawn map that Max had grabbed from the counter at Sierra Designs.

Now they drove down the eastern spine of the Sierras, on 395, with loaded packs, and a map that promised magic.

They didn’t notice the motorcycle following them through the night.

Mad Dog, Max, and Roger arrived at the trailhead just before dawn. They carried sleeping bags and two tents, because Mad Dog insisted on one for herself. They carried no stove, because they planned to build fires at night. Max and Mad Dog studied the map while Roger sat cross-legged underneath a Jeffrey pine and chanted. He took off his clothes then, and pulled his purple satin robe from his pack and put it on. Max and Mad Dog exchanged glances—but Roger shouldered his pack so they did, too—and the trio hiked across a meadow and through a dense pine forest, and up a series of rocky switchbacks toward what Roger thought was Shadow Lake, or Cedar Lake—he could be fuzzy with details.

“No one told me this was going to be a death march,” Mad Dog said, after the group had been hiking straight up for an hour and a half.

Max grunted. “Maybe if you’d cut down on the cancer sticks, it wouldn’t hurt so much,” he said.

“Thanks, jerkhead,” Mad Dog said.

“We create our own pain,” Roger interjected. “We can replace it with love. Love is all around us, if we can only be here…”

“Jesus Christ, Roger,” Mad Dog said, “you give even hippies a bad name. Will you can that life-is-bliss routine while we climb this freakin’ mountain?”

After 40 or so switchbacks, they came upon a deep blue lake ringed with fir trees. At the far end was a low, cavelike opening, so obscured by brush it was barely visible, and a path to the right of it. They found a flat rock that jutted into the water, opened a giant bag of gorp, and looked at the map. They found the large blue oval, encircled by trees. They also saw that while the path next to the cave continued up to more switchbacks, on the map was etched a dotted line that headed straight into the dark hole in the stone. It was one thing to study maps and plan great adventures. Crawling into blackness was something else.

“It stinks in there,” Betsy said. “No way am I going. We don’t even know if the map’s accurate. And even if it is, I don’t trust Jim. And…”

But Roger was already gone. It would take an hour to hike back to the trailhead, and then another hour to drive to the ranger station. And what would they tell the ranger? That they had followed a map drawn by a madman, that their idiotic adventure had led to them losing their maybe-unstable friend, who had disappeared into a cave they were afraid to enter?

“Listen,” Betsy said urgently. “I heard something.”

“It’s the wind,” Max said.

“No, listen.”

They stopped, and they both heard it, something faint and rhythmic. Something that sounded like “Om.” It was coming from the cave.

“Roger!” they both shouted.

“C’mon in!” Roger yelled.

Betsy and Max stared at each other again. Should they go?

“Head for my voice,” Roger yelled.

“I’m not going to crawl in…” Betsy said, but it was too late, because Max—careful, button-down Max—was already on his belly. Betsy followed.

After just 10 minutes of scraping forward, toward Roger’s voice, they saw him silhouetted against daylight at the cave’s far end. They emerged onto an oblong swath of emerald grass. They stared at each other, and then at the map, and then up the canyon ahead, which is where the map indicated they should go.

“Trust the universe,” Roger said, and entered the canyon.

They followed the canyon for a mile, until they came to a place where walls stretched up 400 feet, sheer as glass. In front of them was air. The canyon stopped there, and they couldn’t see what was below.

They all looked at the map. On it was a stick figure, leaping from a ledge into a tiny pool. On the little zero of blue was drawn a happy face.

“This seems to be the way,” Max said, frowning.

“There is only one path, and we’re on it,” Roger said.

“No way I’m jumping off a goddamn cliff,” Betsy said, sitting down in the middle of the trail, trying and failing to light one of her cigarettes.

She did jump, though, after Roger and Max. They landed in a lake, only 20 feet below. They managed to pull themselves and their packs out and they lay there, panting.

They sat in silence and shivered and looked around them. They saw the hidden path—invisible from the top of the ledge high above—and they followed it away from the lake, away from the cliff.

“I think I heard something, like a splash,” Betsy said, looking back at the lake. They all looked in the same direction, but saw nothing.

The path led away from the lake and alongside a boulder field and then past three smaller lakes. After two hours, they left the fourth lake and entered a dark forest, which narrowed to another canyon, and then plunged into a deep gorge, where it dead-ended at a wall of solid white granite.

Roger sat down and chanted, and Betsy lit one of her cigarettes. Max studied the map and took out a compass, and studied the map again. Betsy said she heard something in the woods, and now what the hell were they supposed to do, anyway?

Max ignored her and looked from the map to a thick bush of thorns at the bottom of the steep walls. He crouched down by the bush and dug underneath a triangular rock until he managed to pull it up. “C’mon,” he said, “here’s the tunnel.” It was pitch black, and smelled like something had died in it recently. They heard squeaking.

“I’m not going in there,” Betsy said, but of course, Roger had already squirmed into the opening and was wriggling downward.

“Suit yourself,” Max said, “but please cover the hole once I’m in, and good luck finding your way back to the car alone.” Then he started for the hole.

Betsy looked again at the woods, and she thought she saw movement, so she shoved Max aside and dove in. Max followed, but he went feet first, and when he was almost entirely swallowed, he grabbed the triangular rock and pulled it back into the hole.

They were in the tunnel for an hour, and Betsy freaked out once and started screaming until Max, who had managed to turn his body, grabbed one of her ankles and told her they couldn’t go back, it was too tight, they had to keep moving forward. Roger chanted, which seemed to help.

Finally, they emerged into twilight and a deafening roar. They were on the bank of a river, raging with spring runoff. It looked at least 100 feet across and impassable. Max studied the map, and found what looked like a bridge, but there was no bridge, just huge boulders and whirlpools and frothing whitewater. They huddled together as the sky darkened, and all three shivered, and even Roger shut up.

None of them slept well, and when the sky lightened, their situation looked no better. Roger studied the map and walked 20 paces downstream, to where the map showed the bridge. But there was nothing, just a large Douglas fir whose roots reached to the water’s edge. He walked down to the river, studied it from every angle, even looked at the roots. That’s when he saw the rope. It looked like it stretched across the river, but he couldn’t see that it was tied to anything on the far side. Instead of calling to the others, he grabbed the rope and waded into the water. He hadn’t taken three steps before the current swept his feet from under him and he went horizontal. But he hung onto the rope, his feet dangling downstream, and pulled himself hand over hand until he got to the other side, where the water was calmer and where, he saw, the rope was tied to another tree. By then, Max and Betsy, worried at his absence, had come down to the edge and witnessed Roger’s crossing.

Soon, all three students were on the other side, where they followed a trail through a meadow, up the side of another waterfall, down another gorge, and around another lake. They walked until they came upon a field of wildflowers next to a small, singing stream. At the far end of the stream was a tidy little stone structure.

“This,” Max declared, looking at the map, then all around them, then back at the map, “is where magic lives.”

The flowers looked like enormous, psychedelic Frisbees. There were strawberries, too, red as fire trucks, big as apples. The water from the stream tasted like Fresca and was filled with golden trout, which apparently had never seen a worm on a hook before. The bluebirds were fat and chatty.

The evening wind sounded like music, and the morning sun brushed their faces like gentle kisses. They woke to birdsong. Most days they hiked. They napped in the afternoons, in a little meadow above the camp, in warm, soft grass. They lay on their backs and looked at clouds and talked about what they would become. But they didn’t want to become anything, really. Not then. They all wanted to stay in this place forever.

Even the rain was warm and fragrant, and when it fell hard, they retreated into the little stone shack, which had a wood-burning stove. Next to the stove was a hand-hewn rocking chair and a stack of legal pads filled with equations and a few decks of playing cards and a wall lined with canned food. They stayed for three weeks, and during that time they witnessed the most powerful thunderstorm they’d ever seen. But even the booming of the thunder and the crackling of lightning and the drumming of the rain on the tin roof sounded like lullabies, and the three students slept soundly.

The morning after the storm, when Roger was off tromping around—“seeking truth,” he said—Mad Dog and Max looked at clouds and Mad Dog brushed her hand against his and one thing led to another, right out in the meadow. Roger seemed to know what had happened when he returned, because every evening after that, he would announce that he was going to seek truth, and that he would be gone at least a couple of hours. When he came back, the stars would already be out and Mad Dog and Max would be in their separate tents, smiling.

It really was a magical time—even when Roger cried once, one afternoon when they were on their backs, looking at wispy, pink clouds. He said he was so happy, and that he was afraid to go back, that he wasn’t depressed, and why couldn’t he feel happy like this all the time? What was wrong with him? Mad Dog and Max told him nothing was wrong with him and no one had to go back—not for a long time—and that as long as they were happy now, why worry about the future? Later, they worried that Roger had been crying other times, that they had only witnessed it once.

Then one morning, Mad Dog came sprinting back into the peaceful little camp, yelling that she had seen someone in the woods, and he was staring at her. Max said that was impossible, who could be out here? No one would ever be able to find the place. Could it have been a bear? No, Mad Dog said, it wasn’t a damn bear. It was a kid.

“It’s the spirit of the woods,” Roger said, and Betsy told him to shut his LSD-addled yap, this was serious, and she was scared.

“There’s more than one way in,” Roger said, “and there’s nothing to be scared of.” Max and Betsy ignored him, as they had learned to do when he talked about things like mastering fear and spirits.

Max tromped out into the place Mad Dog said she’d seen the kid, but he didn’t see anything. Neither of them saw anything the rest of the time they were there, except for crimson and purple sunsets that looked as if they’d been splashed onto the sky in hues that didn’t exist elsewhere, and stars so thick and sparkling the students didn’t need flashlights, and a high, hard blue sky that made them think of nothing at all and everything at once.

It’s said that time outdoors will change a person, that getting away from it all is really about drawing closer to what matters. It’s said that divinity bleeds from a single blade of grass, that God pulses in every molecule of a lonely stream, and it’s no coincidence that so many holy visions take place on mountaintops and desert bottoms. But the weeks the students spent in the magic place that summer of 1975 didn’t seem to change anyone in obvious ways.

Except for me.

Sometimes after dinner, before Roger walked away from the fire, pretending that he wanted to meditate on the sunset alone, to give his friends privacy, they would all talk about returning to the magic place. It was then that Roger said something odd. He said that the three of them would probably never return to this place together, that in fact, very few people would ever come again, because the way in was so difficult.

“But we found it, Roger,” Max said.

“There’s a freakin’ map, Maharishi,” Mad Dog said.

“Maybe,” Roger said, “but who knows if that route will work after we leave?”

Max and Mad Dog thought that was strange, but it was late. They wanted to be alone, as young lovers do, and even though they appreciated Roger, and worried about him, his aphorisms were kind of hard to take, so they didn’t say anything. Later, they sometimes wished they had.

Late spring turned to summer and Max had a family reunion to get to, back in Ohio, and they had already stayed two and a half weeks longer than they had planned. On the hike out, they found the hidden path next to the cliff from which they’d jumped, and they climbed it. Even though their meadow had been warm during the day and chilly at night, the sun had been beating the higher elevations, increasing the snowmelt. Runoff was fierce when they arrived at the river, and what had been fast before was a nightmare now. The river had risen five feet and the rope, once straight, bulged in an arc downstream. Max went first, and he coaxed Betsy onto the rope. They got some mouthfuls of water and it was terrifying, but they made it. When they got to the far side, they turned and saw that Roger was sitting by the bank, cross-legged again. Max and Betsy looked at each other, and they were scared, and they yelled at their friend. He wasn’t going to do something stupid, was he? But then Roger grabbed the rope and started pulling himself across, and the lovers laughed. Roger made it across and they pulled him onto the bank and then, before either Max or Mad Dog could figure out what he was doing, Roger pulled a Swiss Army knife from his pocket, and opened it and sliced the rope tied to the root, and the rope across the river flew downstream. Then he used the knife to unravel the knot on the rope and tossed it into the raging river.

“Are you nuts?” Mad Dog yelled.

Roger smiled. “It’s a beautiful place, but it should not be easy.”

“How will we ever make it back there?” Max screamed.

“There’s another way in,” Roger said. “I shared it with the spirit.”

The students left the river, and hiked through the canyon, then crawled through the cave, and then made it to the trailhead. They approached Max’s Jeep, which was covered in dust. Someone had written “Abandoned” on one door.

“Hah!” Roger said. “That’s funny.”

Mad Dog left Palo Alto at the end of the summer and drove south to Los Angeles, where she took a job as a production assistant on a movie directed by a friend of one of her film professors. It was about a space alien that induces such terror in humans who land on its asteroid that they kill themselves trying to escape their imaginary fears. The crew liked Mad Dog’s tough talk and good looks and general competence, and they hired her again, and again, and she never made it back to the Sierra. Four years after she crossed the river on the rope, she was one of the top assistant directors in Hollywood. She wrote her own screenplay then, a thriller called “Beyond the Lost Lake.” It was about three students who stumble on the site where a plane full of marijuana crashed in the mountains. At first unaware that they are being trailed by mafia thugs, the students escape by jumping off of a cliff and miraculously surviving. Each studio she sent it to told her the same thing: “Too much Deliverance, not enough sex.”

After that, she wrote another screenplay, about a young man who struggles through emotional illness, and writes poetry, and only finds happiness when he walks through a secret passage and into a hidden paradise.

“If you’re going to have fantasy, you need laser guns,” one of the studio suits told her. “Isn’t depression a downer?” another suit asked. “What about if we make the guy a girl, and give her telepathy. And what if she falls in love with a bear? Or Sasquatch? The love scene will be edgy, but think of the word of mouth!”

Max enrolled in an MBA program in Ohio, then took a bank job in his hometown of Cleveland. Enough said.

Roger hung around Palo Alto for a few years, working off and on at Sierra Designs, but eventually was let go for good when a new manager grew weary of customers complaining about the guy quoting Carlos Castaneda and blowing on his harmonica when all they wanted was a Gore-Tex jacket. He took a job at a bakery in Mountain View after that, and he would ride his bike there at 3:30 every morning. He spoke to Mad Dog and Max on the phone every few weeks after their Sierra adventure, then every few months, and after a while, no one heard from Roger anymore. When he stopped showing up at the bakery and disconnected his phone, it was as if he had disappeared.

The new manager at Sierra Designs would have certainly fired Jim, too, but he left before the new manager showed up, just a few weeks after the red-haired lady and her kids came into the store and started all the commotion. He didn’t disappear, like Roger. He died. One of the neighbors in his apartment noticed a bad smell, and he called the cops, who found Jim’s body. It had been a heart attack. The San Francisco Chronicle ran a feature story two weeks later, entitled, “Mountain Man a Mystery Even in His Absence.”

It turns out, Jim was from Kentucky, and he had been arrested for attacking a man hitting his dog (but he was never imprisoned). He had been a math major, too, and up until his untimely death, he had been tutoring kids in East Palo Alto, even taking them on hiking trips to Pt. Reyes National Seashore. And he had been in love, according to the newspaper story, but his wife had left him years earlier. And he was rich. Apparently, Jim had been a card counter—a good one—and every month or so, he had been driving to Reno, where he would go from casino to casino, counting cards and playing blackjack. He earned enough to invest several hundred thousand dollars in a local start-up. The story mentioned all of that. It also mentioned the outrageous rumor that the “well-known and slightly intimidating repairman” had discovered a secret hideaway deep in the mountains some years earlier. And it finished with his puzzling legacy—the hand-written, notarized will he had left taped to his desk. The note listed his bank account numbers and locations, and it left everything to a woman and her child he barely knew—the red-headed lady and her dreamy little kid.

I didn’t take it personally that Jim hadn’t mentioned me. He hadn’t even noticed me. People usually didn’t. My mom didn’t, because she was so worried about my dreamy little brother. The students, for the most part, didn’t notice me because I stayed behind them on my motorcycle when they drove to the trailhead, and stayed hidden when I followed them through the woods and off of the cliff and across the river. I’m pretty quiet when I need to be. Roger was the only one who noticed me (except for Mad Dog, who I scared one morning when she was doing her business), and the only one I talked to. He talked to me about all sorts of things: fitting in, and getting lost, and how to find peace in a world so filled with chaos, and whether it’s OK to keep magic places secret when so many people need magic. Even though I was just an undersized 16-year-old with a perpetual sneer, I could tell there was something wrong with him. For one thing, he kept calling me “Spirit,” which creeped me out, even after I told him my name was Eddie. For another thing, he kept telling me that life was suffering and people were cruel, and that love was the answer. If anyone else had talked to me like that, I would have said something smart-ass.

He showed me the secret book, too. It was twilight, the second week of my first summer in the Sierra. We were watching the sunset, listening to the plaintive trills of birds mourning the day’s passing. Roger handed me a leather-bound tablet of yellowed and flaking pages. I don’t know where he had found it. Burnt into the rough cover leaf, in surprisingly delicate script, were the initials “J.M.” I asked if it was Jim’s and Roger said no, definitely not. Roger let me touch it, but wouldn’t let me open it. He said its author had wanted others to see nature’s beauty, and that I should look around me before I looked inside the book.

“Right,” I said, and rolled my eyes. If you remember being 16, you probably understand my response.

He told me if I helped others, I would help myself, and he said he wished he were better at helping others. “Spirit,” Roger said, one warm spring day, “bring the little boy here. He needs this place.”

That must have been what Jim thought, too, when he’d slipped my brother the map. So I did bring him to the magic place. But my brother did not really like the outdoors, and he didn’t really need the secret hut. He just needed something to occupy that big, dreamy brain of his. My mom used the money Jim left her to find that something—in an accelerated math program at a private school. Now my kid brother’s working on computers. He says someday they’ll be small enough to fit on a person’s desk. It seems to make him happy, though I can’t fathom why anyone would need a computer instead of an adding machine. But I never was much of a businessman.

Me? Turns out, I was the one who needed the magic place. I returned there every summer for the next three years. I loved being there in late August, when shadows were lengthening and the Sierra days shortened and you could smell the coming cold. I would pack in canned food, and I would spend my afternoons replenishing the firewood for the stove, and mornings and evenings I would read about bullfighters in Spain and hunters in Africa and fishermen in Cuba. Roger had lugged in the books. He told me he wasn’t much of a reader, but that he thought I might find what I was looking for if I checked them out. He knew I was looking for something.

So as winter blew its chilly breath on our hidden meadow, I walked the dusty trails of Yoknapatawpha County and I felt the fluttering caress of the butterflies in a place called Macondo, and as the season changed, so did I.

When I finished high school, I enrolled in college. That was thanks to Roger. Even though he called me “Spirit,” and even though there was something off with him, I think he knew I was just an angry, confused kid, an older brother and a forgotten son who wanted to be a man. Roger helped me find the way.

But he stayed missing. His parents called the Palo Alto police in the fall of 1979 when they hadn’t heard from their son in six months, and when the cops searched Roger’s apartment, all they could find were some incense sticks and, in the refrigerator, shriveled sprouts. The police tracked down Max and Mad Dog, but they didn’t tell the cops about their hiking trip from four years earlier. After another six months, the cops stopped looking. A month later, Roger’s parents received a letter in the mail, on yellow paper from a legal pad, with a dried wildflower larger and more drenched in color than any they had ever seen.

“I love you,” Roger had written. “I’m safe. Stop looking for me. I am found.”

Roger had given the note to me, the last time I saw him at the hut, four years ago, in 1979. I stayed all summer, and one drizzly afternoon in August, he loped up the hill beside the stone hut and disappeared behind a ridge. When he came back, he unwrapped something tied in plastic and told me I was ready to see it—to see inside it. I sat by the wood-burning stove and listened to the fierce popping and hissing of wood and when I opened the book—the same ancient, leather-bound one with the initials J.M. etched into its cover—I almost choked on the dust.

“We are now in the mountains,” J.M. had written, “and they are in us, kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us.” That was dated 1868.

I didn’t know who J.M. was at the time. Now, I suspect I do. In 1872, he wrote, “No amount of word-making will ever make a single soul to ‘know’ these mountains. One day’s exposure to mountains is better than a cartload of books.” Later the same year, he wrote, “God has to nearly kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons.”

I read for an hour, and J.M. seemed to grow more disenchanted with humanity and enthralled by the glory of the mountains on every page. At some point, I fell asleep, and when I awoke, to the sound of bad harmonica music, Roger was sitting next to me, in his purple robe. The book was gone, and neither of us spoke of it again.

When I left a week later, he gave me the note for his parents. He asked me to drive to Arizona, or Nevada, he didn’t care, and to pick a post office—any post office—and to mail it from there. And I did. I did it because Roger saved my life. I don’t know where I’d be if not for Roger. I suspect it’s somewhere bad.

I was lost when I followed Roger and his friends to the magic place, and even after feeling the alpine sun on my face and the spongy grass beneath my feet, I stayed lost. Roger tried to show me the way during those long summer weeks. He tried to tell me that wounds could be healed, that if someone just kept looking, he might find his way. For him, the answer was in the stars, and the morning sun and the flowers like Frisbees, but he saw that those things weren’t my answers. He gave me some books to read, and he told me I should try to describe a mountain peak in a paragraph. He said that for some people, words lead to peace.

That’s what I’ve been looking for. I’m a writing fellow at Stanford now. I’m walking the same halls once inhabited by Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner and Ken Kesey, men who tried to use words to re-create the earth, and the sky, and in so doing somehow managed to limn the borders of peace, and love, and what it means to be alive. I tell my students—kids not much younger than I—that conveying joy or grief with language is difficult, and capturing a mountain peak is impossible, and that artists fail every day of their lives when they attempt to describe their perfect, shimmering visions. I tell them a capacity for enduring such failure is terrible and painful, and yet they must possess it if they want to continue.

It’s been three years since I saw Roger at the stone hut. I’ve returned there every summer, to read, and to write, and to try to feel the glory, or the peace, or the relief that Jim felt, and Roger, and J.M., and sometimes I do feel it. I hiked to the stone hut last year—1982—and the flowers still rioted, and the stars still blazed and the fat, golden trout took my hooks like the fish were little kids and I had candy. I tried to imagine Roger happy, and I tried to envision a life in the mountains, under the vast, uncaring sky. I failed, but I kept trying.

I’m back in Palo Alto now, and I have bad days sometimes. In those dark moments, I feel like walking into the mountains forever. Once, the dean “suggested” I visit the university hospital, where doctors gave me pills. For the four months I took them, I didn’t think about the mountains much, or leaving this world. I don’t remember what I thought about. It was a fuzzy, worry-free time, and I hated it. I tossed the pills away. I’d rather have bad days.

I think of Roger often, and the magic place. Sometimes, I wonder how anyone can remain true to himself in a world like ours, where the opportunities to go astray are so many, so tempting. Isn’t that why people grab tents and sleeping bags and head into the wilderness in the first place? Not to find a hidden meadow, or a hushed and gentle valley, but to find their true, uncorrupted selves? To find peace? Isn’t that why J.M. built the stone hut in the first place?

Roger told me that what made him happiest was lying in the mountain meadow grass, soft as dreams, and looking at the high, hard sky while he thought of everything and nothing at all. He told me that maybe he would be able to do that somewhere else, but he wasn’t sure. He told me he didn’t want to take the chance.

People say that secrets should be shared, and that hoarding magic is selfish. But the place where magic lives was never my secret. First it was J.M.’s, then Jim’s, and he’s gone, and then it belonged to Max, and Mad Dog, and Roger, and then Roger cut the rope across the river.

Roger would say that no one owns anything, that the universe belongs to us all, and that those lucky enough to know this secret need no other knowledge, because they are rich beyond measure. Roger said that to me once. Roger said lots of things, and they sounded goofy to my young ears, and I didn’t—and don’t—know how anyone could live according to them in a world that seems so hard, and often so mean.

The rope across the river wasn’t the only path to the place where magic lives. Roger found the other way in, and he showed me. I’m not sure why. Maybe he thought that someday, I might need to return.

Eddie Oglander taught creative writing at Stanford University from 1981 to 1983, which is when he submitted this story, and the magazine— mistakenly we now believe—declined to publish it. According to Steve Friedman, who played basketball with Oglander in a Menlo Park rec league and to whom Oglander gave his map (p. 88), the young man struggled with mental-health issues, off and on, until 1987, when he disappeared on a solo camping trip near Mammoth Lakes, California. His body was never found.