See More Vultures

'Illustration by Jackie McCaffrey'

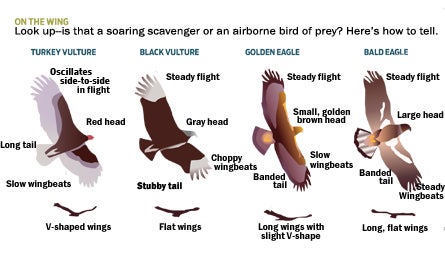

Talk about an image problem. Vultures are so underappreciated that the name itself is an insult. But seen from a thousand feet below, turkey (left) and black (right) vultures, the two species most common in North America, are a beautiful sight as they glide effortlessly on broad, near-motionless wings. In fact, many people mistake high-flying vultures for eagles and hawks, even though genetic evidence puts them in the stork family. Sure, their sharp beaks and bald heads are better adapted for gobbling carcasses than winning beauty pageants (bare skin simplifies post-meal cleanup). But by consuming dead animals, these birds play a crucial ecological role in preventing disease transmission. Here’s how to identify–and appreciate–these natural recyclers on your next hike.

Flight

Vultures are too heavy to stay aloft for long by flapping alone, so they seek a boost from thermals–rising columns of warm air. Turkey vultures, with six-foot wingspans, leave their roosts as the morning air warms. Smaller but heavier black vultures wait until stronger updrafts develop later in the afternoon. Cruising at 40 mph and gliding from one thermal to another, a vulture can remain aloft all day, traveling more than 100 miles while seldom flapping its wings.

Conservation

Vultures were once trapped and killed in the erroneous belief that they spread diseases. In fact, their digestive acids kill bacteria and viruses found in decomposing flesh. Loss of nesting habitat remains a threat, but North American vulture populations are strong and increasing, partially due to a messy side effect of human development–roadkill.

Hunting

Turkey vultures are among the few birds with an acute sense of smell: They can detect the gases produced by decaying flesh, which helps them find carrion even while flying over dense foliage. Black vultures hunt by sight alone and fly high to locate food, watching both for carcasses and congregating turkey vultures. Although smaller, black vultures are more aggressive, and will block out turkey vultures from a carcass–and sometimes even attack and kill newborn cattle and pets.

Range

Turkey vultures prefer open and semi-open areas like grasslands and farmland, where food is easier to locate. They’re found throughout the United States and southern Canada during the summer, and migrate to southern states during the winter, with some subspecies traveling as far as South America. Black vultures prefer warmer, low-lying habitats, and only overlap with their kin in the Southeast and lower Mid-Atlantic.

Breeding

Vulture pairs form monogamous bonds following aerial and ground courtship rituals. After mating in early spring, the female lays two eggs in a shallow depression in a cave, abandoned building, or sheltered area. Both parents share the egg- and chick-tending duties, feeding the nestlings by regurgitation. Chicks can fly at 10 to 13 weeks, but stay with their parents for several months longer. When their eggs or chicks are threatened by raccoons or owls, vultures will regurgitate semi-digested meat as a foul-smelling defense.