Return of the Natives: Paddling and Hiking Channel Islands' Lost Gem

'Santa Cruz Island'

THE WAVES AT SANTA CRUZ ISLAND roll shoreward in gentle sets of three-foot swells. I wait until the tide is lowest and paddle hard, jabbing at a couple barnacle-encrusted rocks for balance on my way out of an SUV-size sea cave, one of 326 on the island’s cliff-riddled shore. Out on the open water, I steer my 12-foot sit-on-top kayak into a tiny inlet near Scorpion Rocks, pausing to watch a gang of California brown pelicans take flight. Two harbor seals surface and blink their bulging eyes. Neon orange garibaldis dart through the seaweed below my boat. The weather is golden, and just yards away, the island appears so quiet and pristine with California buttercups in bloom, I have a hard time imagining that this place was ever anything but a perfectly preserved haven.

But Santa Cruz, located 19 miles off the Southern California coast, wasn’t always so achingly gorgeous. In fact, it used to be a pigsty. Literally. Thousands of feral pigs, brought here first as livestock in the 1800’s, rooted through the soil, feasting on native plants, leaving barren slopes vulnerable to invasive weeds. Golden eagles followed the pigs, which were easy pickings for the large raptors. Soon, the eagles began preying on island fox, a species living nowhere else in the world, as well.

By 2004, the pigs had all but decimated nine of the island’s 12 endemic plants, and the fox population, once in the thousands, had dipped below 90. It looked like the pigs wouldn’t stop until they’d chowed right through this delicate ecosystem—an environment so unique that biologists often call it “America’s Galapagos.”

In most places, it’s impossible for land managers to eradicate an invasive species completely, but on an island it’s feasible to hunt down every last one. Thanks to a joint effort between The Nature Conservancy and the National Park Service (which own 76 and 24 percent of the island, respectively), the pig looting was stopped in one of the biggest (and fastest) species eradication projects ever conducted. Between April 2005 and July 2006, gunners-for-hire slaughtered 5,036 pigs. After more than a year of subsequent monitoring for stray swine, officials declared biological order restored in August 2007.

In March 2008, I visited Santa Cruz Island to explore a place biologists say is more pristine than at any time in the last 170 years. I came to observe a rare phenomenon: an ecosystem reborn.

After paddling back to the anchorage, I head to camp at eucalyptus-scented Scorpion Ranch and find only two of 40 sites occupied. The camp is on the northeast corner of Santa Cruz, one of five isles in Channel Islands National Park. It’s day one on my journey, and the truth is I can’t help feeling a little piggish myself. Before the seven-mile paddle along the coast, my sea-kayaking guide, Andy Babcock, had wheeled a handcart full of falafel, pale ales, tuna steaks, and Peet’s coffee over to his favorite campsite. No suffer-fest this weekend. Babcock stashed the grub into steel lockers near the site’s picnic table. He said the lockers were called “pig boxes” because the park service installed them to keep the porkers from ravaging campers’ supplies back when they had the run of the place.

In the evening, we feast on the ferry-packed groceries, then turn in early to recharge for the next day. Come first light, I’ll walk 15 miles southeast to Del Norte Camp on the island’s isthmus. I’ll gain 1,200 feet, crossing the highest point on the National Park side of the island and pass through ten different biomes. It’s a traverse, Babcock tells me, that’s rarely done. But it’s the best way to see the island’s rugged interior.

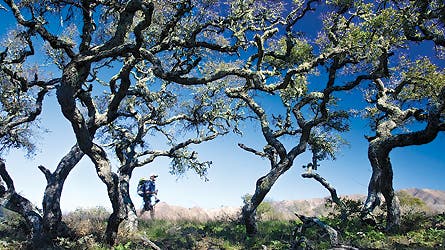

Early the next day, just 50 steps down the Scorpion Canyon Trail, I spot two island foxes playing in a dry creek bed, and I pause to watch the cute, four-pound predators pounce on grasshoppers in the morning sun. A quarter-mile later, the route makes a sharp turn and I begin a steady climb, gaining 700 feet along grass-lined clay trails to a junction with an old ranch road and a barren, sepia-tone ridgeline. The views here are postcard perfect—bristly green grass giving way to cliffs and a deep blue ocean with islands that seem to hover above the white-capped waves. About four bazillion Southern Californians live within eyesight on the mainland, but I won’t see a soul here all day. Santa Cruz is popular with dayhikers and paddlers, but walk a couple hours in any direction and you’ll be the only human.

I cruise another five miles along Montañon Ridge, a craggy spine with patches of prickly pear and rooftop views into sandy coves. Campo Del Norte lies another six miles away in a small shaded grove, and I’m starting to think of dinner and the flask of scotch in my pack. But after a confusing trail junction (midisland trails are growing over without regular hoof traffic), I’m jarred back into the moment by the sight of a decomposed pig. It’s hairy, the size of a Labrador, and must have had some serious dental problems.

The origins of Santa Cruz’s eco-rampage can be traced back to 1839, when Spanish diplomat Andres Castillero moved onto the island and subsequently built one of the biggest sheep ranches in California. Docile farm pigs, originally brought here for food, broke through their fence lines and escaped into the wild. Once on the loose, they became a menace—pretty much overnight. “Feral pigs are devastating,” Babcock tells me. “It only takes two years for them to turn from a fat, pink farm pig to fearless, longhaired animals with tusks that can pierce metal.”

That a tame porker with a future no brighter than the glint from a butcher’s cleaver can go completely primal seems pretty inspiring in a weird way. I can be soft and pink myself from time to time, but I like to think I’d harden up if left to fend for myself, just like those rampaging pigs.

That’s not to say I’d like to take on well-armed conservationists intent on restoring order. “We did triage on the island,” says Rachel Wolstenholme, when I meet her on my third day, at Prisoners Harbor, a 3.5-mile hike from Del Norte. Wolstenholme is the island restoration manager for The Nature Conservancy, and she’s accompanying me on a four-mile out-and-back on the Pelican Bay Trail, from Prisoners to a pristine arc of white sand.

The path crosses Nature Conservancy land, and a group of volunteers who’d come to pull invasive weeds for the weekend wave hello as we pass. We cover the rolling terrain at a decent clip, dropping into steep drainages, climbing tight switchbacks, and finally rising onto a grassy plain where we head off-trail toward stunning yellow blooms. Wolstenholme graciously ignores my bad pig jokes on the way.

The conservancy started its island overhaul in 2002. “We bred island fox and bald eagles in captivity while trapping the golden eagles and transporting them to Northern California,” explains Wolstenholme. And they started getting rid of the pigs, too. Unlike the feral sheep that also once roamed here, the pigs couldn’t be trapped and shipped elsewhere. State regulations forbade it because of their potential to spread disease. So TNC hired a New Zealand company called ProHunt to “dispatch” the pigs, fencing the island into five sections and shooting them from helicopter and on foot. By the end of ProHunt’s work, there were enough dead pigs to feed an army.

“There was a lot of bacon,” Wolstenholme says self-consciously. The carcasses fed hunters and other islanders, and TNC used some to feed bald eagle chicks. But most decomposed and were recycled into the ecosystem.

With the pigs gone, native plants are springing back to life. The coreopsis bloom, the biggest in a century, is such a bright electric yellow that you can see the biggest patches from the mainland. On top of that, Wolstenholme says bald eagles are nesting here for the first time in more than 50 years, and the island fox has rebounded, its population now topping 400. The island is in full rebirth; it just needed a little tough love.

As I hike back to the pier to wait for the ferry, I recall something Babcock said when I first arrived. I’d asked him why there were so few visitors; the island seemed so empty. “No locals ever come out here,” he said. “They say there’s nothing out here. Well, yeah! That’s the point.”

I’d argue that there’s plenty out here. Miles of rugged shoreline, trails lacking only hikers, secluded campsites galore, and stunning island wildlife—there’s simply nothing that doesn’t belong.

Plan It | Santa Cruz Island

Season: You’ll have Santa Cruz Island to yourself (and soak up the fairest weather) from October to April.

Ferry: Island Packers ($60 roundtrip for campers, islandpackers.com) runs daily trips from Ventura to Santa Cruz Island.

Outfitter: Aquasports has led Santa Cruz Island paddling trips for 24 years ($175/person/day, islandkayaking.com).

Book and Map: Pair Trails Illustrated #252 Channel Island National Park ($10, natgeomaps.com/trailsillustrated) with A Guide to East Santa Cruz Island, by Don Morris ($13, trafford.com).

Camping: Campsites ($15/night) are open year-round on all five islands in CINP. Check availability at reserveamerica.com.

Contacts: National Park: (805) 658-5730, nps.gov/chis. The Nature Conservancy: (415) 777-0487, nature.org.

The Way: From Los Angeles, take US 101 north 62 miles to Victoria Ave. in Ventura. Exit left, and head 0.8 mile to Olivas Park Drive. Make a right and motor 2.3 miles to Spinnaker Drive. Island Packers and the Channel Island National Park visitor center are down on the right.

Photography by Michael Darter