Was the First Appalachian Trail Thru-Hiker a Fraud?

Long-distance hiking has its own Book of Genesis, and it is a dusty tome: old, its prose antique and glinting with a starry-eyed wonder that is sparse in today’s cynical world. The book is entitled Walking With Spring, and in it, author Earl Shaffer writes: “The trail ascended through spruce thickets along Katahdin Stream.” It is his first-person account of what the book’s cover describes as “the first solo hike of the legendary Appalachian Trail.”

“In every other direction was spectacular scenery,” Shaffer continues, enthusing over what he saw on August 5, 1948, when he was 29 and finishing up his four-month, Georgia-to-Maine journey. “Westward were Ripogenus Flowage and Moosehead Lake. Someone has said that a giant mirror was broken over Katahdin and the lakes are the pieces.”

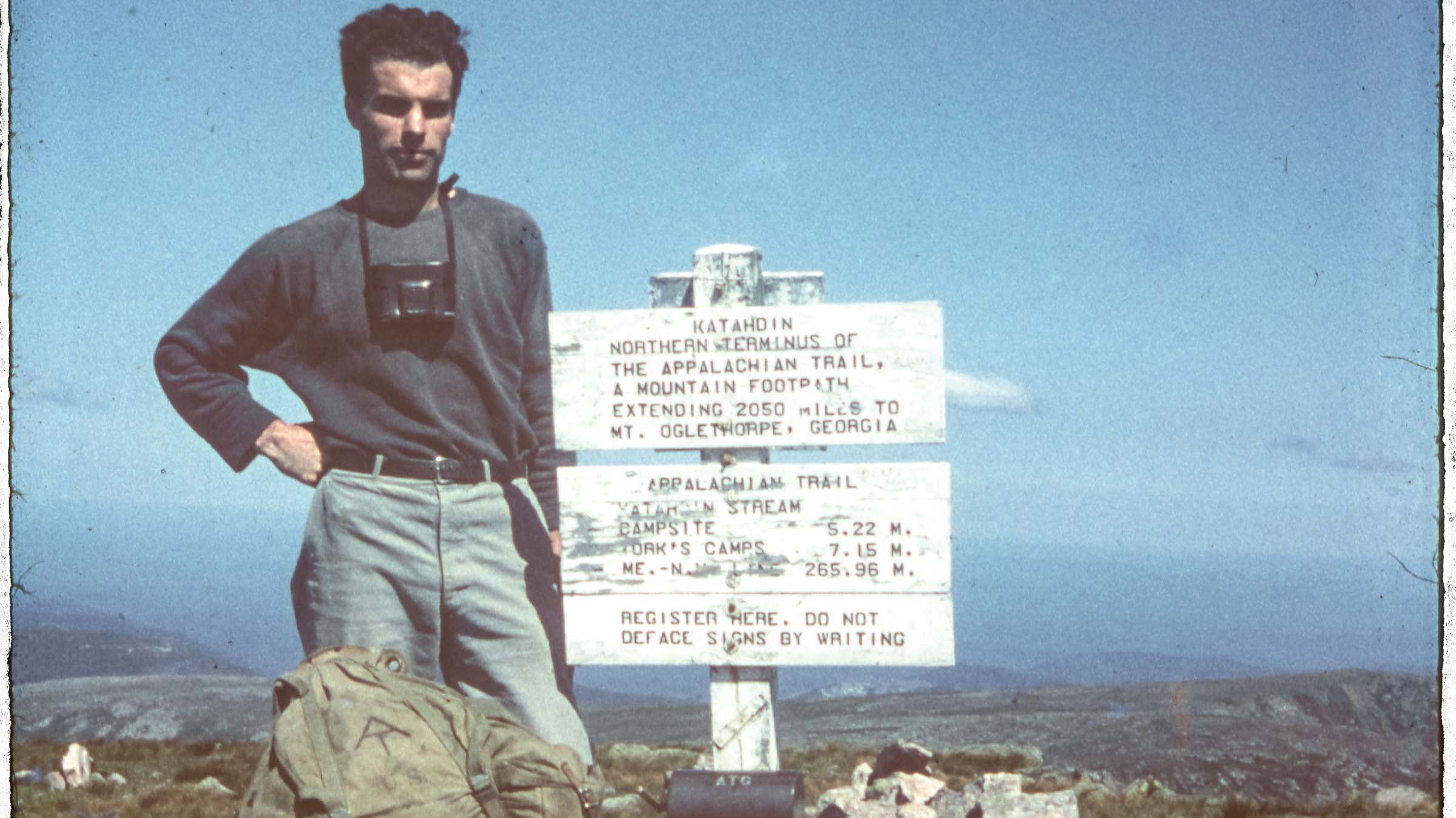

As Shaffer reaches the AT’s northern terminus, he paints himself as a hero in touch, almost, with the dawn of time. “Step by step across the rocks,” he writes, “the Lone Trail-hiker came to the cairn on Baxter Peak, said to be the first spot in the United States touched by the rays of the rising sun.”

No one could publish such rhapsody about a thru-hike today, when more than 1,000 hikers knock off the entire AT every year. But make no mistake: Earl Shaffer (1918-2002) was a legend in his time—and still is. He embarked on his hike during a period when even the trail’s architects believed that a 2,000-mile trek was beyond human capability. The AT, first conceptualized in 1921, was completed in 1937, but fell into neglect during Wold War II. Shaffer, a veteran, hiked its unmaintained length in Army boots, without socks, filling his shoes with sand to toughen his feet and stave off blisters.

Temperamentally, he was the archetypal thru-hiker. Shaffer was a seeker, a sensitive and largely unsuccessful poet who never had a romantic relationship, eschewed steady employment, and struggled throughout his life with depression and financial insolvency. Given the trail name “The Crazy One” late in his life, he had much more in common with the dreamers of today’s hiker community than the man most consider the AT’s second thru-hiker, Gene Espy, an orderly engineer who once summed up his 1951 walk in three bland words: “I enjoyed it.”

Shaffer showed generations of thru-hikers what’s possible on the AT. But there’s a problem: He may have been a fraud.

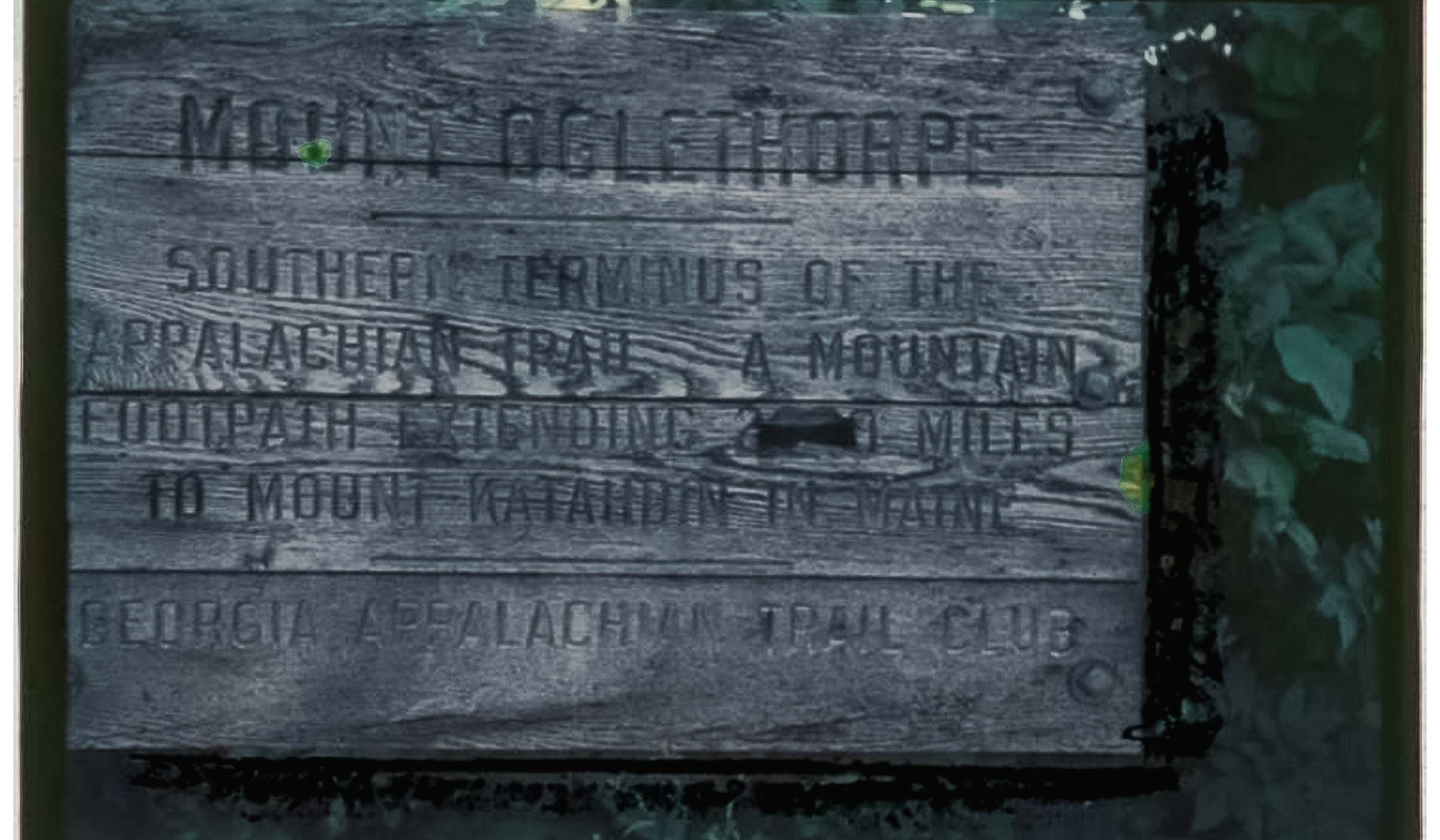

In 2011, a retired West Virginia prosecuting attorney and amateur AT historian, Jim McNeely, published a 164-page report alleging that, among other divergences, Shaffer failed to start his 1948 hike atop 3,288-feet high Mt. Oglethorpe, which was, at the time, the AT’s southern terminus (it was moved to Springer Mountain in 1958 due to overdelopment). As McNeely tells it, Shaffer, due to a navigational error, launched his hike 3.2 miles to the north, atop the slightly lower Sassafras Mountain, and didn’t realize his mistake until a full year after he reached Katahdin, in August 1949, when that month’s National Geographic ran a 19-page story on the AT. The article noted the most prominent feature atop Oglethorpe—a 38-foot high obelisk honoring Georgia’s founder, General James Oglethorpe—“a beacon,” to quote Nat Geo, “visible for miles from land or air.”

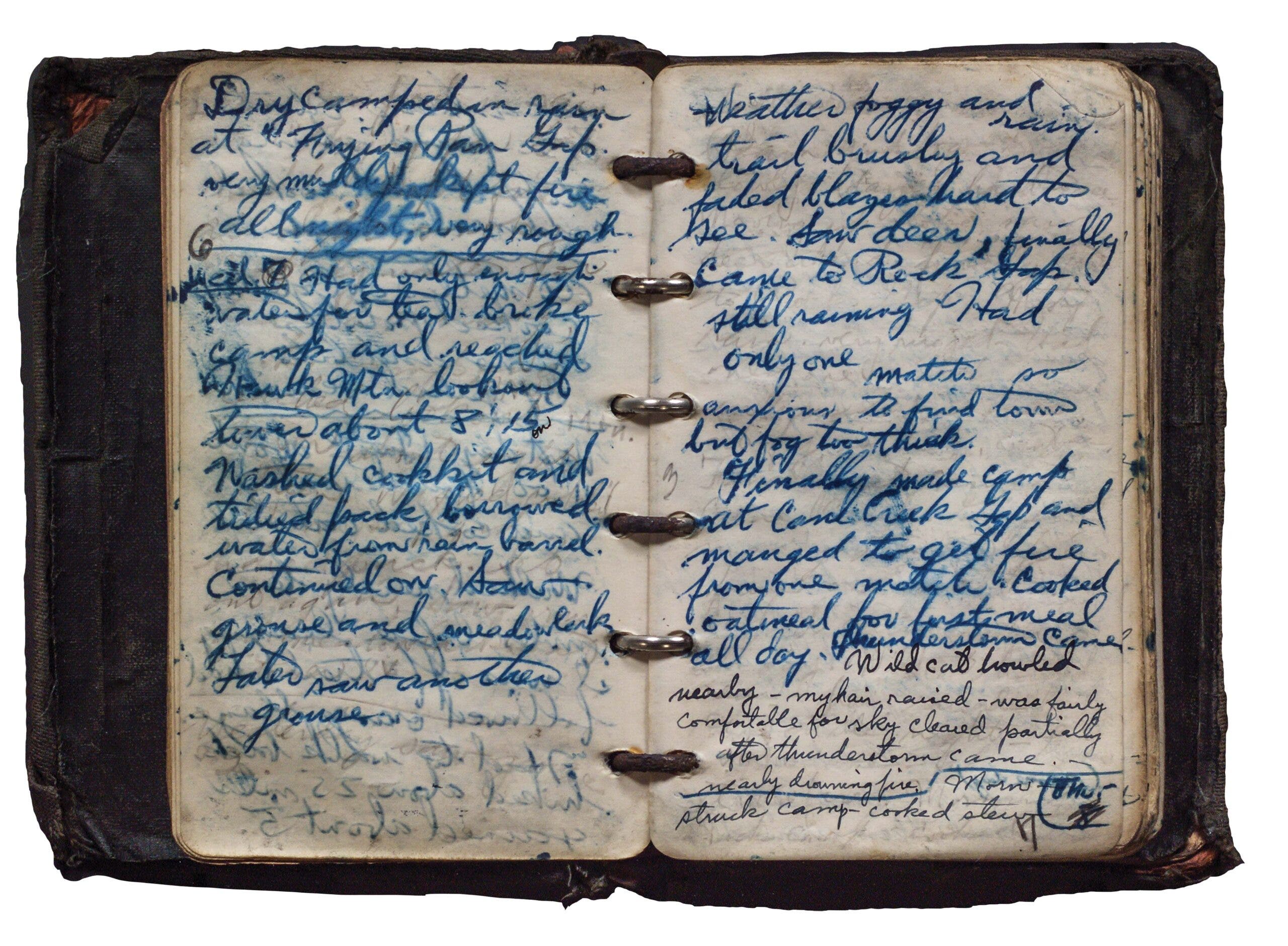

“Shaffer panicked when he read about that monument,” McNeely guesses, “because he never saw it.” As McNeely readily points out, the obelisk doesn’t even get a mention in Shaffer’s trail journal, now housed in the archives of the Smithsonian. In Walking With Spring, though, Shaffer celebrates a “tall white shaft of native marble” in the book’s opening paragraph. To McNeely, those words are a fictional insert—and just one among several of Shaffer’s sins. McNeely’s report, which tracks Shaffer north to Rockfish Gap, Virginia, is engaged mainly in exposing the discrepancies between the flawless hiking machine of Walking With Spring and the fallible human who inhabits the journal. McNeely purports that the Crazy One failed to hike 170.31 of the 769.31 miles between Oglethorpe and Rockfish Gap. With cool disdain, he asserts that Shaffer “took short-cuts, made his own way, accepted motor vehicle rides, and walked highways.”

Upon its release a decade ago, McNeely’s report met a stony reception. On whiteblaze.net, Bill O’Brien, the editor of the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association’s newsletter, called it “pure B.S. It boils down to a couple of car rides,” O’Brien wrote, skirting the Oglethorpe issue. “You weren’t there, Mr. McNeely. Could it be Earl was sensitive to an offer of kindness and Southern hospitality from strangers? … I don’t know and neither do you.”

The report got ink in only one newspaper, The Roanoke (Virginia) Times, and in that story, Brian King, the publisher for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, characterized McNeely’s work as unworthy of nuanced consideration. “The fact does remain that Earl was the first to report a thru-hike,” King told the paper. “The fact also remains that the ATC accepted that report of a thru-hike. And that’s where we stand.”

No one seemed inclined to accept that 74-year-old Jim McNeely is, for all his obsessions, a perfectly logical man with an impressive resume. He’s twice served as a West Virginia state legislator, and in the early 2000s, he was the elected prosecutor in tiny Summers County, West Virginia. In challenging the keepers of Appalachian Trail lore, though, he hit a brick wall. For nine years, his report simply gathered dust.

But in recent years, historical reassessment has surged in the U.S., and an important question has shaken our country: Were our alleged heroes actually heroic? Sure, the questions surrounding Earl Shaffer only involve hiking. But I began to wonder: Is McNeely right? And if Shaffer did fib in his book, should he be stripped of his title as the AT’s first thru-hiker?

Jim McNeely first harbored suspicions about Shaffer’s hike in the late 1990s. While reading Walking With Spring, he was jarred by a sentence in Chapter 1: “Reaching the summit of Oglethorpe near sundown and finding it exposed to a cold and merciless wind, I backtracked to a rickety leanto near a rickety firetower and stayed there.”

McNeely is an aficionado of old maps, and in 1985, he took a Georgia-to-Maine thru-hike that saw him frequently veering off the current AT to explore the significantly different midcentury Appalachian Trail. Like Shaffer had claimed to, McNeely started his hike on Mt. Oglethorpe. “There never was a shelter on Oglethorpe,” he says. In 1948, the closest shelter was 3.2 miles away, McNeely explains, atop Sassafras, which also happens to boast a firetower. But would Shaffer really have schlepped all the way from Oglethorpe to Sassafras in the cold, windy dark, just to sleep? To McNeely, Shaffer’s assertion jumped out as “an inconsistency. I just stowed it away,” he says. “That’s what prosecuting attorneys do—we stow away inconsistencies.”

Over the next decade, McNeely channeled his cartographic passions into other projects. He ventured into the mountains of North Carolina to retrace the footsteps of Horace Kephart, a naturalist whose 1903 memoir, Our Southern Highlanders, considered the folkways of impoverished Appalachian mountain dwellers. After an ancient guidebook told him of the defunct North Carolina Road, in Virginia, he spent five days scrabbling through the brush until he was able to map several miles of the now-invisible thoroughfare.

In 2008, after McNeely learned that Shaffer’s family had deposited his papers in the Smithsonian archives, he traveled to Washington, D.C. to read the trail journal. While there, he also enlisted a librarian to show him the photos that Shaffer shared in slideshows to hiking clubs. When the librarian got to one photo, allegedly taken atop Mt. Oglethorpe on April 4, 1948, she shuddered, according to McNeely.

“Look,” she said, “it’s been altered!”

There was black tape masking the right edge and the bottom of the photo, and when McNeely peeled it away he discovered that it concealed green leaves on a tree branch—leaves that wouldn’t have been present in early April. Did Shaffer actually shoot the image in July 1950, when he took a well-documented automobile tour along the AT? Did he tape over the leaves to cover up the fact that he never set foot on Oglethorpe in 1948?

McNeely didn’t just have a hunch anymore. “When I looked at that slide,” he told me, “that’s when I knew.”

During the first two months of our acquaintance, McNeely and I only spoke over the phone. His slightly nasal West Virginia twang became familiar to me, as did his frequent digression into philosophy. “Bill,” he told me at one point, explaining his investigative thinking, “I’m a Sherlock Holmes fan, so the question I always ask myself, piecing together a narrative, is, ‘Are all the dogs that are supposed to bark barking? And are all the dogs who aren’t supposed to bark not barking?’” He styled himself a raconteur.

I knew that in time I’d need to meet McNeely in person—he is, after all, the rebel taking on the hiking establishment. First, though, I needed to learn about the man he’s criticizing, so on a cold day in January I drove seven hours south from my home in New Hampshire to the western suburbs of York, Pennsylvania, to explore Earl Shaffer’s childhood stomping grounds.

Shaffer and his four siblings grew up poor in the hamlet of Shiloh, in a log cabin his family came to call The Old Place. The cabin is still intact, albeit engulfed by modern additions, and the surrounding seven-acre property remains, too—a lovely green Eden carved with mown paths. At its base is Derry Creek, and after the current landowner granted permission, I strolled down to its ice-crusted banks and was reminded of how, as a kid, Shaffer swam here, and canoed, and hunted for muskrats. He did everything with his best friend, Walter Winemiller, from whom, he’d later write, “I learned most of my woodcraft and my abiding love of all outdoors. Walter Winemiller was a pardner [sic] such as one may have only once in life.” A fellow World War II soldier, Winemiller was gunned down storming the beach on Iwo Jima in 1945.

Shaffer, too, served in the South Pacific, as a radio repairman. His team secured communications on Japanese islands and lived with the constant threat of enemy soldiers poised to attack. He came home shell-shocked, leery of other people, lackadaisical about seeking work, and inclined to make frequent solo escapes into the hills on his motorcycle.

Shaffer could have gone to college on the GI Bill, but he felt he had a higher calling: He’d written 200 poems during the war and hoped to be remembered as the poet of World War II. In 1947 he saw his route to immortality when he read that no one had ever backpacked the entire Appalachian Trail in one go. “He thought, ‘I’ll hike the AT, and I’ll keep a travelogue and take pictures and then sell a book,’” says David Donaldson, a York special education teacher who is, with Maurice Forrester, the co-author of the only Shaffer biography, A Grip on the Mane of Life. “He figured, ‘Then I can sell my poetry.’”

Early in 1948, Shaffer ordered trail maps from the ATC. The maps never arrived in the mail, though, so that April, Shaffer took a bus to Jasper, Georgia and began navigating his way north using an oil company road map. By his own admission, he “strayed at times.” He also caught a short lift from a friendly forest ranger in Virginia. But by 1948 thru-hiking standards, his off-piste wanderings were acceptable, and that November, ATC Chairman Myron Avery applauded Shaffer. “Your trip and the circumstances under which it was made,” he wrote to the hiker, “have undoubtedly served to greatly increase interest in Appalachian Trail travel.”

Shaffer couldn’t sell his book, though, and he spent the next 17 years living in a cramped apartment above the garage at The Old Place while he freelanced as a used furniture salesman.

It was only in old age that he attained recognition. In 1998, he decided to hike the AT again, at age 79, exactly 50 years after his first AT tour. By the time he reached Katahdin, there was a gaggle of reporters in tow. The Today Show flew him to New York for a post-hike interview, and the following year, when he showed up in Damascus, Virginia for the Appalachian Trail Days festival, so many autograph-seekers mobbed him that it took him an hour to walk two blocks to breakfast. Finally, his book began selling.

Earl Shaffer died in 2002 and is buried in Shiloh Cemetery, and as I stood by that grave in January, I found myself hoping that he is resting in peace. But then my phone buzzed in my pocket.

Jim McNeely was sitting six hours south of me. Our plan was to spend a day up near Bearwallow Gap, just off Virginia’s Blue Ridge Parkway, so McNeely could show me why be believes Shaffer skipped an 18.33 mile stretch of the AT immediately north of there on May 14, 1948. But when a blizzard swept in, we were forced to downscale to a masked meeting—the country was still in the throes of the pandemic—in my room at the Howard Johnson motor lodge in Daleville, Virginia. In the interest of hospitality, I pilfered a couple Styrofoam bowls from the breakfast bar and poured two Covid-safe servings of salted peanuts—one for me, one for McNeely.

When McNeely arrived, slightly early, he was lean and nimble, with fine features and a longish, unruly thatch of brown hair. He was driving a 2004 Chevy Astrovan. An array of cold-weather camping clothing hung neatly from a pole in the back, and his 12-year-old mutt, Geva, lingered nearby, wagging her tail. Proudly, McNeely showed me the “2,000-miler” cloth patch sewn onto Geva’s harness and told me she earned it, hiking large swaths of the historic AT with him. I decided against interrogating the veracity of this claim.

For the next five uninterrupted hours, McNeely held court, focusing on what he believed was a breakthrough in his investigation. In recent weeks, prompted in part by my inquiry, he’d gone beyond poking holes in Shaffer’s Oglethorpe claims to construct his own narrative of what Shaffer did on April 3 and 4, 1948. At the core of his version is the photo that appears, sometimes cropped, on the cover of every edition of Walking With Spring: an April 1948 picture that captures Shaffer from behind, the sun at his back as he bears a loaded pack and gazes east over Georgia’s Sequoyah Lake, which sits roughly 10 miles northeast of Shaffer’s supposed starting point, in Jasper, Georgia. It’s a hopeful image of a young man setting out on an historic journey, but it was, troublingly, not taken anywhere near the Appalachian Trail. How did Shaffer end up at this spot?

To answer this question, McNeely first asked where Shaffer bought his road map. He established that there were two gas stations selling maps in Jasper in 1948. One was a Gulf, the other a Texaco, and McNeely reckoned that both stations were likely dispensing a 1946 Rand-McNally map that errantly placed Mount Oglethorpe several miles west of its actual location.

“Bill,” McNeely told me at the HoJo, “I’ve looked at the map very closely. I bought a copy on eBay.”

The errant 1946 map, as McNeely tells it, routed Shaffer past Sequoyah Lake on his way to Mt. Oglethorpe. To get from Jasper to Oglethorpe, he should have taken a different route. “It was a human error,” McNeely said, trying to be generous, “and I admire Earl Shaffer. He may have flunked an ethical test, but he was so determined and so tough. He got lost. He was constantly running out of food. I would have given up!”

Listening, I found myself puzzling over which ethical code Shaffer violated. Today, there are ironclad rules regarding timed runs on the AT: If you want to beat Belgian dentist Karel Sabbe’s 2018 record sprint of 41 days, 7 hours and 39 minutes, you better cover every inch of the trail. But when the question is, “Who gets to call themselves a thru-hiker?” the rules are much more lenient. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy awards 2,000 mile patches to hikers (and, yes, dogs) on what it calls the “honor system” and doesn’t mind if folks hop in a vehicle to avoid “a flood, a forest fire, or an impending storm.”

In 1948, there weren’t any standards at all. Indeed, says Mills Kelly, a George Mason University history professor at work on a book about the AT, “The very idea of hiking the entire trail in a 12-month period simply didn’t exist, and the trail wasn’t fully blazed the way that it is today.” Kelly holds that, “Asking if it was an ethical breach is the wrong question.”

Maybe so. But isn’t lying simply wrong, no matter the year or the trail condition? I have to admit that I’m with McNeely in doubting Shaffer’s claim that he hiked miles in the dark to find shelter on the night of April 4. And I can’t see how a hiker following the AT would end up at Sequoyah Lake. In my mind’s eye, an indicting vintage film flickers to life: I can see Shaffer hunched over his writing desk, scrambling to account for his navigational blunders.

Was Earl Shaffer capable of lying? As far as I know, no one but McNeely has accused the man of mendacity, and the arc of his life hardly suggests that this humble backwoodsman was a scheming opportunist. I think, though, of Shaffer’s poetic ambitions—of how he wrote all that careful, impassioned verse amid the strain of war in the South Pacific and of how his earnest literary efforts got him nowhere. At some level, he could have felt the world owed him some recognition, and his 1948 hike was, by the standards of the day, just three miles from perfection.

It’s conceivable, I think, that Shaffer minted the story about Oglethorpe, reckoning it was just a little white lie. And McNeely has seemingly endless evidence that this white lie happened. As we sat there at the HoJo, he kept gesturing toward a large accordion file of Shaffer papers he’d brought. “Do you want to see the 1948 aerial photographs I have of Oglethorpe?” he asked.

I didn’t want to spend the next week at a Howard Johnson’s, subsisting on bad coffee and worse danishes, so in time I cajoled McNeely outside. Geva, waiting there, was ecstatic to see us. Both of us pet her, and it was only after the Astrovan disappeared that I realized McNeely never consumed a single peanut. The Styrofoam cup of water I poured him was likewise untouched.

At this juncture, I wish that I could supply you with a new, unknown hero of the early AT. The story of early twentieth century hiking, as told thus far, includes almost no one but upper-crust WASP men. The trail’s two progenitors, Myron Avery and Benton MacKaye, were both Harvard alums, and hiking’s earliest scribes tended toward snobbery. In one 1905 Appalachia magazine essay, Tufts University professor Charles Ernest Fay suggested that simple country people were too dull-minded to enjoy alpine adventure, being inclined to look at mountains as “so much waste land, as occupying space that might otherwise come under tillage.”

Earl Shaffer proved the blue bloods wrong. But now a sliver of doubt shadows his name. In reporting this story, I wondered: Isn’t there another underdog out there? And for a moment I thought I found him—or, I should say, a whole group of them.

In 1994, a 73-year-old Florida retiree, Max Gordon, wandered into the ATC headquarters in West Virginia and proclaimed that 58 years earlier, in 1936, he and five other members of Boy Scout Troop 257, based in the Bronx, had hiked the length of the Appalachian Trail during their summer vacation. All of the young hikers, aged 15, 16, and 17 at the time, were Jewish. Gordon’s narrative placed them on the trail during the summer Adolf Hitler was hosting the Berlin Olympics, and his 1994 memories, shared with Appalachian Trailways editor Judy Jenner, were touching. “We were poor kids,” Gordon told Jenner. “My mother made my sleeping bag, and it wasn’t fancy at all, no feathers, just a couple of blankets sewn together. I could pull part of it over my head to keep the dew off.”

In the early 2000s, a Boston-based optical physicist and hiker, Arthur Gaudet, was so enchanted with Gordon’s account that he spent 15 months scrounging for evidence that the 1936 Boy Scout hike actually happened. There was very little evidence for Gaudet to find, though. In 1994, Gordon produced no photographs and was unable to furnish Jenner with contact information for any of his alleged hiking partners. Gordon died in 1996. There is no contemporaneous documentation of the Boy Scout hike, and Gaudet’s 39-page report is, as a result, filled with hopeful but hard-to-swallow assertions such as, “The lack of Bronx newspaper announcements isn’t too difficult to explain.”

Reflecting on Gordon now, Jenner says, “I don’t think he was lying. I think that he probably took a really long hike—and that it grew in his mind as he aged.”

Earl Shaffer remains the AT pioneer we’ve got, and in deciding whether to call him a hero, I think back on a chat I had with his biographer, David Donaldson, while visiting York.

Donaldson, who’s 60, met Shaffer on the AT in 1998 and hiked with him through New England that autumn. A few years later, he purchased a split-level ranch from Shaffer’s brother, John. The property adjoins that of the Shaffers’ childhood home, The Old Place, which means that, as Donaldson and I stood in his kitchen, we were gazing out upon the hillside on which Shaffer and Walter Winemiller played as kids.

“He’s a hero to me,” Donaldson said.

“Just to you?” I said.

“Well, our country’s so divided now,” Donaldson said. “We can’t even agree on who we should honor these days. But what does the Bible say? If there’s anybody that’s perfect, let him cast the first stone.

“Earl grew up in the Great Depression. He went to World War II and fought for his country and then he came home and tried to face down his frailties. He could be difficult”—Donaldson grinned—“but he was a friend.”

Eventually, Donaldson told me of his first trail encounter with Shaffer, at a hostel in Tennessee. “He was going to just hike past the hostel,” Donaldson said, “but we were grilling burgers and the smell wafted down to the trail. Earl did a double take and turned back, toward us. Then four of us stayed up until midnight that night, listening to him tell stories under the yellow bug light on the porch.”

Later, Donaldson hiked through Maine with Shaffer. He was there when the Crazy One ascended Katahdin at age 79. “Earl was like a spider climbing a wall,” Donaldson says, remembering the last rubbly quarter-mile pitch. “He’d curl his fingers and grab onto a nubbin and claw himself up. He stopped to look for footholds. Sometimes he’d reach for a handhold and fail and climb downwards, looking for a new route. He wasn’t fast; he was an old man.”

Throughout his life, Shaffer had failed in so many of his ventures; he carried old grievances and jealousies. But he kept going, a flawed pilgrim bent on arriving.

Donaldson tells me, “Nothing was going to stop him.” And I think to myself that on another day, it could have been me out there. It could have been you. It could have been Jim McNeely, even. After all, hikers are mostly the same: clambering inexpertly along, freighting our sins and shortcomings to the summit, just trying to reach a warm pile of rocks bathed in the first rays of the rising sun.