Preview: Was the First Appalachian Trail Thru-Hiker a Fraud?

Outside+ members can read the full version of this story from our print edition, and so much more. Sign up today.

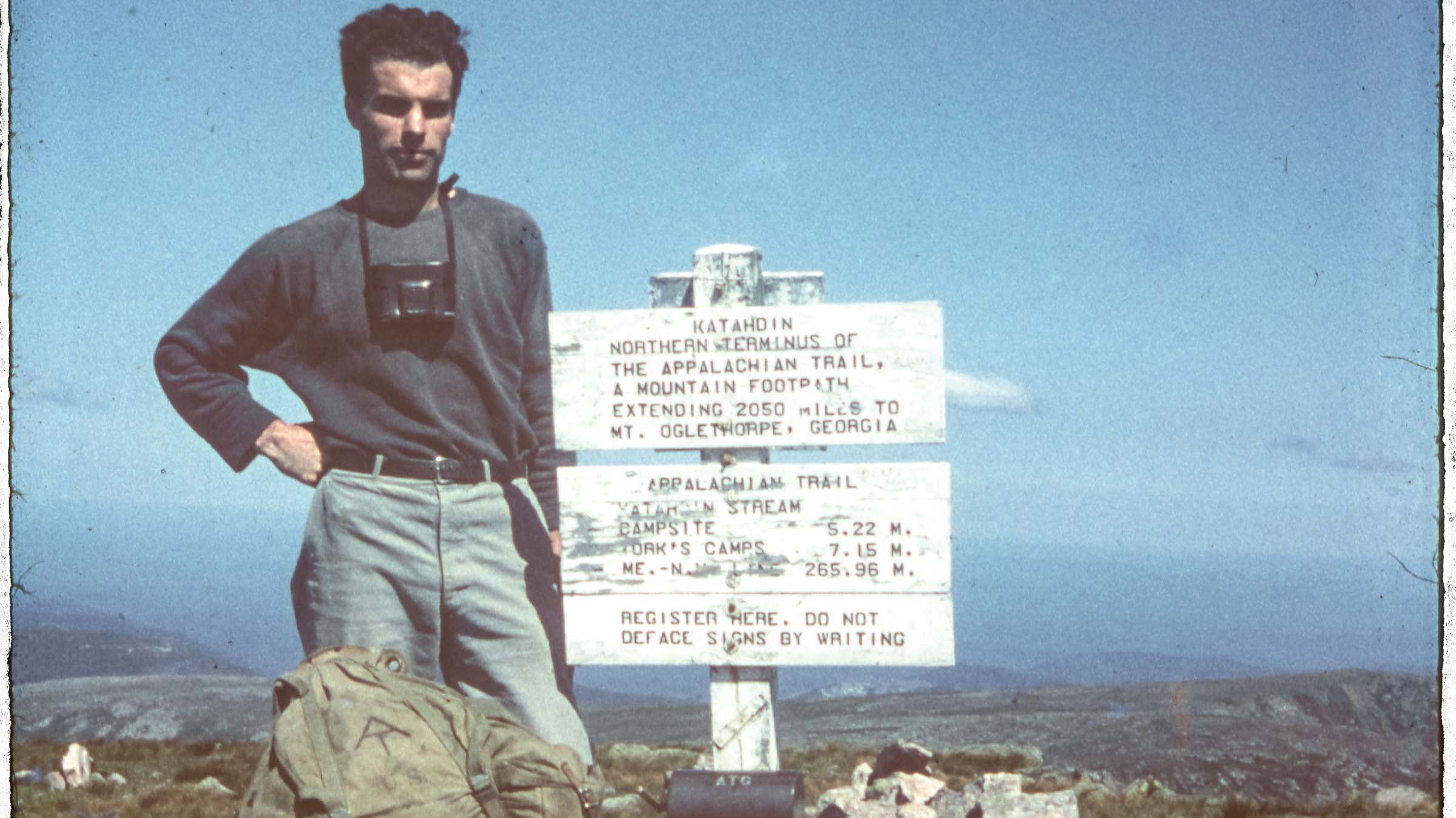

Long-distance hiking has its own Book of Genesis, and it is a dusty tome: old, no longer in print, its prose antique and glinting with a starry-eyed wonder that is sparse in today’s cynical world. The book is entitled Walking With Spring, and in it, author Earl Shaffer writes: “The trail ascended through spruce thickets along Katahdin Stream.” It is his first-person account of what the book’s cover describes as “the first solo hike of the legendary Appalachian Trail.”

“In every other direction was spectacular scenery,” Shaffer continues, enthusing over what he saw on August 5, 1948, when he was 29 and finishing up his four-month, Georgia-to-Maine journey. “Westward were Ripogenus Flowage and Moosehead Lake. Someone has said that a giant mirror was broken over Katahdin and the lakes are the pieces.”

As Shaffer reaches the AT’s northern terminus, he paints himself as a hero in touch, almost, with the dawn of time. “Step by step across the rocks,” he writes, “the Lone Trail-hiker came to the cairn on Baxter Peak, said to be the first spot in the United States touched by the rays of the rising sun.”

No one could publish such rhapsody about a thru-hike today, when more than 1,000 hikers knock off the entire AT every year. But make no mistake: Earl Shaffer (1918-2002) was a legend in his time—and still is. He embarked on his hike during a period when even the trail’s architects believed that a 2,000-mile trek was beyond human capability. The AT, first conceptualized in 1921, was completed in 1937, but fell into neglect during Wold War II. Shaffer, a veteran, hiked its unmaintained length in Army boots, without socks, filling his shoes with sand to toughen his feet and stave off blisters.

Temperamentally, he was the archetypal thru-hiker. Shaffer was a seeker, a sensitive and largely unsuccessful poet who never had a romantic relationship, eschewed steady employment, and struggled throughout his life with depression and financial insolvency. Given the trail name “The Crazy One” late in his life, he had much more in common with the dreamers of today’s hiker community than the man most consider the AT’s second thru-hiker, Gene Espy, an orderly engineer who once summed up his 1951 walk in three bland words: “I enjoyed it.”

Shaffer showed generations of thru-hikers what’s possible on the AT. But there’s a problem: He may have been a fraud.

In 2011, a retired West Virginia prosecuting attorney and amateur AT historian, Jim McNeely, published a 164-page report alleging that, among other divergences, Shaffer failed to start his 1948 hike atop 3,288-feet high Mt. Oglethorpe, which was, at the time, the AT’s southern terminus (it was moved to Springer Mountain in 1958 due to overdelopment). As McNeely tells it, Shaffer, due to a navigational error, launched his hike 3.2 miles to the north, atop the slightly lower Sassafras Mountain, and didn’t realize his mistake until a full year after he reached Katahdin, in August 1949, when that month’s National Geographic ran a 19-page story on the AT. The article noted the most prominent feature atop Oglethorpe—a 38-foot high obelisk honoring Georgia’s founder, General James Oglethorpe—“a beacon,” to quote Nat Geo, “visible for miles from land or air.”

“Shaffer panicked when he read about that monument,” McNeely guesses, “because he never saw it.” As McNeely readily points out, the obelisk doesn’t even get a mention in Shaffer’s trail journal, now housed in the archives of the Smithsonian. In Walking With Spring, though, Shaffer celebrates a “tall white shaft of native marble” in the book’s opening paragraph. To McNeely, those words are a fictional insert—and just one among several of Shaffer’s sins. McNeely’s report, which tracks Shaffer north to Rockfish Gap, Virginia, is engaged mainly in exposing the discrepancies between the flawless hiking machine of Walking With Spring and the fallible human who inhabits the journal. McNeely purports that the Crazy One failed to hike 170.31 of the 769.31 miles between Oglethorpe and Rockfish Gap. With cool disdain, he asserts that Shaffer “took short-cuts, made his own way, accepted motor vehicle rides, and walked highways.”

Upon its release a decade ago, McNeely’s report met a stony reception. On whiteblaze.net, Bill O’Brien, the editor of the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association’s newsletter, called it “pure B.S. It boils down to a couple of car rides,” O’Brien wrote, skirting the Oglethorpe issue. “You weren’t there, Mr. McNeely. Could it be Earl was sensitive to an offer of kindness and Southern hospitality from strangers? … I don’t know and neither do you.”

The report got ink in only one newspaper, The Roanoke (Virginia) Times, and in that story, Brian King, the publisher for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, characterized McNeely’s work as unworthy of nuanced consideration. “The fact does remain that Earl was the first to report a thru-hike,” King told the paper. “The fact also remains that the ATC accepted that report of a thru-hike. And that’s where we stand.”

No one seemed inclined to accept that 74-year-old Jim McNeely is, for all his obsessions, a perfectly logical man with an impressive resume. He’s twice served as a West Virginia state legislator, and in the early 2000s, he was the elected prosecutor in tiny Summers County, West Virginia. In challenging the keepers of Appalachian Trail lore, though, he hit a brick wall. For nine years, his report simply gathered dust.

But in recent years, historical reassessment has surged in the U.S., and an important question has shaken our country: Were our alleged heroes actually heroic? Sure, the questions surrounding Earl Shaffer only involve hiking. But I began to wonder: Is McNeely right? And if Shaffer did fib in his book, should he be stripped of his title as the AT’s first thru-hiker?