Pack Man: The Appalachian Trail Guru

'Winton Porter'

Winton Porter

Packs outside Mountain Crossings

Porter shows Serafin how to drop 10 pounds

Socks drying outside Mountains Crossing

Porter’s boot collection

Stop just dreaming about a thru-hike; make it real! Our online Thru-Hiking 101 class covers everything you need to plan and finish the long-distance hike of your dreams. Start it instantly, complete it at your own pace, access it forever. Sign up now!

Nobody walks by Mountain Crossings without stopping. The combination hostel and gear store and hiker aid station, at Walasi-Yi in northern Georgia, sits quite literally on the Appalachian Trail. It’s the first outpost of civilization that northbounders encounter–and the last for southbounders. Each year, up to 2,000 thru-hikers drop in. Some just pause for the few minutes it takes to grab spare batteries and a Clif Bar. Many linger for a hot shower and a soft bunk and to soak up the history of a lodge that was established in 1937, the same year as the AT itself. Others have no choice but to stop.

Christine Serafin was one of the latter. On a raw morning last March, she limped into Mountain Crossings with a bum knee and an uncertain future. The would-be AT thru-hiker had just completed her first 30.6 miles–only 2,144 to go!–from Springer Mountain to Neels Gap, and she didn’t know if she could go on. One in six thru-hikers make it no farther, and Serafin feared her dream would end here, too.

It hardly seemed fair. Serafin, 66, a former timekeeper at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, had trained diligently and made a significant investment in high-end gear prior to embarking from Springer Mountain. She already had a trail name (Indy Girl, natch). But the burden of carrying a 31-pound pack (before food and water) had caused her right knee to swell. Suddenly, Katahdin was looking about as doable as Everest. Hair coiffed short and dressed in black from socks to ear band, Serafin looked the part of the hip and confident aunt from New York City. But apprehension was written across her face.

Winton Porter, proprietor and unofficial AT guru at Mountain Crossings, didn’t need to guess what Serafin was thinking. Like many northbound hikers, Serafin had been sucker-punched by the deceptively arduous trek from Springer Mountain to Neels Gap. The relatively short distance is arguably the toughest stretch on the AT: The route is surprisingly rugged and steep, with cold and wet weather in the early spring when most thru-hikers tackle it, and it gives the unfit and poorly outfitted no chance to ease in. Countless hikers drag themselves into Mountain Crossings riven with doubts–about their quest and their gear and their resolve. So desperate are they to keep their dream alive that they’ll willingly subject their outdoor knowledge, their basic judgment, even their most intimate possessions to public scrutiny. Serafin was in just such a state. Porter needed only one look to know that she was primed for the Mountain Crossings signature service: the Shakedown.

That smell. Push open the door to Mountain Crossings at the height of thru-hiker season in early spring, and a peculiar aroma assaults the olfactory receptors. It’s a pungent blend of boot leather, toaster pizza, sweat, factory-fresh Cordura, sock funk, and sandalwood-scented massage oil, with undertones of history. It’s safe to say you won’t sniff anything like it anywhere else.

Then again, there’s no outpost quite like Mountain Crossings, which straddles the Appalachian Trail at Neels Gap. So narrow is the mountain notch here that the AT is squeezed into a breezeway separating two squat stone structures. (“The only covered portion of the trail’s 2,100-plus miles,” boasts the Mountain Crossings website.)

Up here, at 3,110 feet, the rhododendron grow tall, waterfalls tumble within earshot, and about the last thing one expects to find is a boutique dedicated to the fine art of lightweight, long-distance backpacking. To label Mountain Crossings a mere gear store, though, is like calling the AT just another trail. In an era of 30,000-square-foot mega-stores, Mountain Crossings unapologetically and exclusively celebrates backpacking in all of its quirky and unsanitized glory. But even that description falls short. The full extent of what Porter and his staff of seasoned thru-hikers provide includes a home for wayward souls, museum of backpacking, gear-testing skunkworks, roadside tourist attraction, coaching service, personal organizer consultancy, and circus sideshow.

Porter has his own take. “We are backologists, shoeolgists, psychologists, and sociologists who happen to sell gear to solve the first two and by default have learned to deal with the last two,” he says.

Which means that the 42-year-old Porter–a tall, loping Georgian prone to calling everyone “brothuh”–runs his business more like an extension of the AT community than a typical retail store. Making someone’s day–by driving a replacement backpack 37 miles up the road to a thru-hiker stranded in Hiawassee or offering chiropractic massage free of charge–takes precedence over making a profit. Short on cash? Then clean the bathrooms or chop wood for half an hour and stay free. Got an emergency? Borrow the beat-up Toyota Previa van to get to town.

The Shakedown, an item-by-item inspection of a backpacker’s possessions, is an extension of Porter’s karma-meets-commerce approach. The typical Shakedown requires at least an hour and as many as four. “Spend that much time with a customer and you’d get reprimanded or fired at most stores,” says Porter. “For us, it builds tremendous loyalty.”

As a result, and despite its remote location, Mountain Crossings hums with activity. Prospective thru-hikers journey here from throughout the Southeast–on a recent visit, customers were up from as far away as Jacksonville, Florida–to receive the full Mountain Crossings treatment. Northbound 2008 thru-hiker Britt Mammenya wrote in the store’s logbook, “I’m sad to leave, but thankful for the rest and advice.”

Visitors also get a dose of AT and hiking history. Inside the former inn, a loosely curated collection of packs lines the walls–from a circa 1920 Adirondack basket to a wooden Trapper John to one of Gregory’s first internal frames. Next to the credit-card machine leans an 11-pound metal hiking staff carried by a southbound thru-hiker (nicknamed Rebar, of course). Hundreds of worn and abused boots hang from every rough-hewn chestnut post and beam. Porter says it’s the start of his Museum of Old Soles. “I’m shooting for 2,175 boots, one for every mile of the AT.”

Porter purchased Mountain Crossings after rising through the executive ranks at Galyan’s Trading Company in Atlanta. He wagered his entire 401(k) account as collateral to purchase Mountain Crossings, then tendered his resignation from corporate America on December 6, 2000 (a framed copy of the letter hangs by the case of frozen burritos). His wife, Margie, co-signed the contract from a hospital bed, where she was recuperating from delivering the couple’s second daughter, Allison. “We gave birth twice in one week,” quips Porter.

Eight years on, Porter finds himself in a spot any passionate backpacker would envy. He’s regularly consulted on equipment design by major manufacturers like Salomon; he’s co-producing (with Speer Hammocks) the Frog Sac, a summer-weight sleeping bag with arm holes; and his shop will likely appear in Robert Redford’s film version of A Walk In The Woods. “Could I have made more money? Yup. Am I richer in other ways? Absolutely,” says Porter.

A long-distance hiker’s backpack presents a Rorschach test of sorts, the contents revealing clues to its owner’s basic personality. Cautious types cram in oversize first-aid kits, emergency whistles, and Mace. The impetuous will carry a solar charger but no lighter. Control freaks schedule every meal and organize everything in color-coded sacks. What then to make of the 62-year-old thru-hiker carrying 125 Viagra pills? Or the hiker known as “Minnesota Smith” who packed nine rolls of toilet paper? Or the guy who pulls out a snorkel mask and flippers?

Porter makes no judgments. He’s seen it all while dissecting the innards of thousands of packs during Shakedowns. Serafin’s backpack presents no surprises to Porter–but provides plenty of opportunities to save weight and bulk.

“You want to ask yourself, What does each piece of clothing do for me? Does it insulate? Does it stop wind? Does it stop rain?” he says. “Nylon zip-off pants don’t do any of those three. If you wear a pair of nylon running shorts over lightweight long underwear, now you have pants that weigh 3.5 ounces instead of two to four times as much.”

As Porter painstakingly analyzes every item Serafin carried–from ibuprofen to the pack itself–he sets aside discards in a growing pile. Around the main salesroom floor, the wet and rank contents of three other backpacks are similarly stacked, like so many yard sales, as staffers Adam Heath and Felicity Keddie go through the same process. Each Shakedown session typically nets 12.5 pounds in weight saved. But some yield far more.

Porter still chuckles about “Ranger Rick,” who staggered in under an 89-pound pack several springs ago. “It took two of us to carry the damn thing. He had three pounds of coffee and three pounds of creamer and sugar in there. We got him down to 34 pounds. He made it all the way to Katahdin,” says Porter.

A pound here and a pound there, and before you know it you’re up to four tons, which is the weight of discarded equipment Mountain Crossings ships back home for thru-hikers every year. Porter’s pretty certain that UPS uses the Mountain Crossings route to haze new drivers. Another 1,000 pounds in food ends up dumped in the hostel’s “hiker box.”

Over near the dressing room, Porter kills more ounces with Serafin. He reaches for a synthetic-fill jacket from one of her piles. “If I swap in a MontBell Thermawrap jacket and you wear it with a midweight underwear top, you now have a 10-ounce jacket system instead of a 16.5-ounce jacket.” Serafin balks. “If you want to integrate it, great. If not, you won’t hurt my feelings,” says Porter.

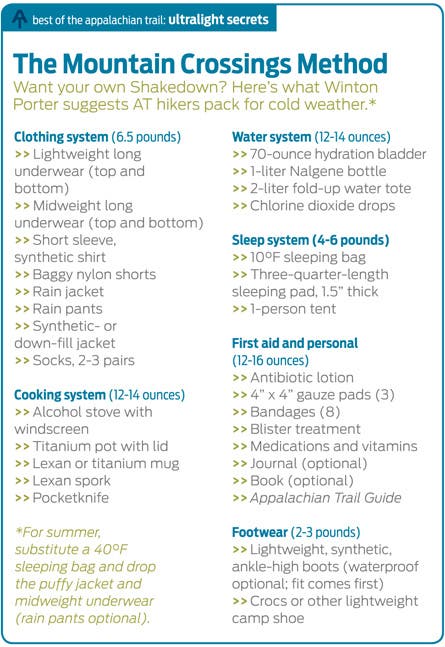

The ounce-saving advice notwithstanding, Porter is no ultralight purist. “Going light with the wrong skill set could get you killed. We sell safety and comfort,” he says. “Lightweight is a byproduct of what we do.” By the Mountain Crossings method, the ideal load is 30 to 35 pounds, including food and water, for early spring conditions, or 25 to 30 pounds for summer, all stuffed into a 3,800-cubic-inch pack. To get there, Porter has developed a studied process based on distinct systems–clothing, cooking, water, sleeping, footwear, first aid and personal (books, maps, and journals)–each driven down to as low a weight as a customer’s budget and experience level allows (see “The Mountain Crossings Method” at right).

Serafin lingers at Mountain Crossings an extra day, waiting out bad weather and mulling Porter’s advice. In the end, she buys the MontBell jacket, trusting in Porter that her new layering system of synthetic T-shirt, midweight underwear, insulating layer, and rain shell, when worn in combination, will get her through the subfreezing nights that lie ahead in the Smoky Mountains. When she shoves off, her base load weighs 21 pounds, lighter by 10 pounds than when she arrived. “That’s a good diet program,” she says.

At last report, Serafin had made it through most of Virginia before flip-flopping to the Maine section of the AT to escape the summer heat. The odds are good that Porter will receive yet another testament to the power of his advice. “That’s what we get back,” he says, pointing to the sprawling collection of inscribed photos pinned to every available surface in the store. In the pictures, men and women pose with beaming smiles and arms upraised atop a rock pile on a distant peak in Maine. “I’m helping people with their dreams.”

Jim Gorman won’t tell us what his Shakedown revealed.