National Parks Confidential: Q & A with Filmmaker Ken Burns

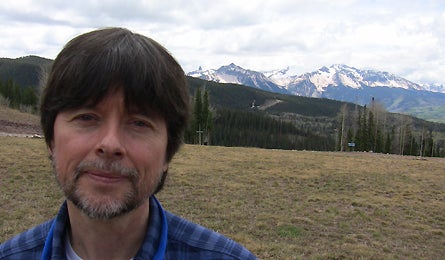

'Burns at the Telluride Mountainfilm Fest'

If you’re expecting the latest Ken Burns film, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, to be a sweeping armchair tour of the country’s most beautiful wilderness, think again. “We didn’t want to make an encyclopedia or travelogue or nature film,” Burns told BACKPACKER last spring in Telluride, Colorado, at the world premiere of his new six-part series. Instead, he and filmmaking partner Dayton Duncan worked to create a very human history. Airing September 27 to October 2 on PBS (see our episode guide), the documentary highlights little-known players and events in the creation of the world’s first national park system–and a good dose of epic scenery, too. BACKPACKER editors Tracy Ross and Jonathan Dorn sat down with Burns for a preview.

BP: You’ve talked about celebrating the “nameless faces” of the national parks. Who stands out for you?

KB: Early in the film you meet African-American buffalo soldiers, the cavalrymen who were the guardians of Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks at the turn of the 20th century. And there’s George Melendez Wright, a Hispanic-American who was the first biologist of the National Park Service. This is important because, even now, you have Hispanic-Americans and African-Americans in this country who do not feel an ownership of the parks. One of the great delights for us is going into schools across the country and showing black and Hispanic kids heroes that look and sound like them. We’re hoping to create a generation of people that will use parks and feel that ownership. Without it, the parks won’t survive.

BP: In introducing the first episode at the Telluride premiere, you spoke emotionally about a backcountry trip in Yosemite that you took during shooting.

KB: I thought Yosemite would be the first natural national park I’d ever visited. [Editors’ note: “Natural” refers to the scenic parks, like Yellowstone, as opposed to the historical parks, like Gettysburg.] On the last day of filming there, we tramped up past Vernal and Nevada Falls to spend the night camping. We’d worked really hard, and I thought I would just fall asleep. But I suddenly realized, “This is not the first.” I had simply forgotten. In 1959, when I was 6 years old, my mother was dying of cancer, our household was demoralized, and my father was absent. He didn’t play catch, he just wasn’t there. But one Friday after school, he took me to Baltimore, where he’d grown up. He put me to bed in his room under his old comforter. He woke me up at 4 a.m., and we left in the dark. We went to Front Royal, at the north end of Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park. We drove through clouds, we drove through tunnels, and we saw deer. I can remember the jean jacket my dad put on me and the warmth of his hand as we walked. He described every tree and rock. We turned over logs and found these bright red salamanders, and I can remember the songs he sang. I’ve sung them to my three daughters, having forgotten–until I went to Yosemite–where they came from.

That’s what happens in a national park. You can stand on the rim of the Grand Canyon and see rock that is 1.7 billion years old, but it matters very much who’s holding your hand. We save these places, and they show us a glimpse of what the land was like before–but there are also intimate histories. Parks are places where we forge connections. It turns out my grandfather took my father to Shenandoah, and I’ve taken my daughters again and again to [historical] national parks, and they’ll take their children. There is, as John Muir said, a practical sort of immortality in that.

BP: There’s a prominent spiritual narrative throughout the film, and a significant religious history to the parks that won’t be familiar to a lot of viewers.

KB: One of the things that hit us over the head [in researching the film] was the essential spirituality at the heart of the park story. As historians, we tend to focus on our political and military narrative, the succession of administrations and political freedoms punctuated by the wars and the hero generals. But we’re also a country that said you could worship God the way you wanted to–that it didn’t have to be in a cathedral. It was inevitable that we’d have Transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau who said, “Europe may have the cathedrals, but we have this beautiful Garden of Eden.” And then comes John Muir, this Scottish-born wanderer who will walk into Yosemite [and see it] as the morning of creation, as being born again in nature in every moment.

The language that everyone used, including Abraham Lincoln, who first authorized Yosemite, was the rhetoric of the Bible. That’s why we named our first episode “The Scripture of Nature”–because the national park idea was born from people who were talking about finding God in nature.

BP: Have you encountered God in the wilderness?

KB: I don’t know whether I’d call it God. But I know there’s a moment when you feel like you are seeing everything new. There is a vivifyingness to everything, a luminosity to the light. Suddenly, things take on a different relationship. You feel a kinship with all things. Those moments are fragmentary at best for most of us, but I’ve experienced them deeply in Yosemite and Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Denali, Glacier, and the Everglades.

BP: Early in the film, you discuss the displacement of Native Americans from Yosemite Valley. It’s a theme that repeats itself from park to park, but many people don’t know that the government took many parks by force. Do outdoor enthusiasts need to apologize for this?

KB: Our shame is in this acquisitive and rapacious thing that we’ve had in our bloodstream as a country that [has led us to] overdevelop this beautiful continent, this Garden of Eden. Thomas Jefferson thought it would take hundreds of generations to fill it up, but we’ve filled it up in less than five. And in every instance, we have displaced the native peoples who were there.

Dayton and I wanted to tell a very complicated story that tolerates the undertow that’s in there. You should understand the geological history, but also the history of native peoples. And [you should learn about] the battles with extractive and acquisitive interests that always look at a stream and say “dam,” look at a stand of timber and think “board feet,” look at a canyon and want to mine in it. Fortunately–and this is the great thing that Dayton and I want to salute–there were some places where Americans said, “No, we have to put up a fight and save them.”

BP: One of your goals is to increase traffic to national parks. But getting the average citizen to visit can take some work, and the frontcountry can be a zoo. How realistic is it to expect casual tourists who may never leave the road to have an experience that will make them fans for life?

KB: People have varying degrees of experience. Backpackers know the great, deep abiding power that John Muir knew, the power that comes from going out there to look at a flower for a minute or a day. But the country needs other constituencies coming if we want to save the parks. As filmmakers, we wanted to translate that power because we know that even a quick visit creates a chance for a transformative experience. We live in a world that erodes our attention, that distracts us from the real experience of nature. Just getting out there, even if you’re just driving through a park, is worthwhile.

BP: Let’s talk about that–about technology and distractions and nature deficit disorder.

KB: As a culture, we are at a hugely critical existential moment, one where people are suspended between being and doing–especially our children–because of this virtual world that we have created. People are just too distracted by their BlackBerries and Facebook. We need to make it a lot easier for families to take camping trips. If we don’t, you will find that backpackers are not a big enough constituency to resist the acquisitive and extractive interests.

BP: It sounds like you’re saying that parks could disappear.

KB: Yes, exactly! Parks are like liberty–it takes eternal vigilance to protect them. We need to understand how ephemeral and transient they are.

BP: Muir and Roosevelt could not have anticipated global warming, which is altering landscapes and migration patterns. Should we be rethinking park boundaries, maybe to change them from geographical boundaries to something more fluid?

KB: When you see the retreat of the glaciers in Glacier, you realize how serious global warming is. Fortunately, the park idea has always expanded. At first, saving land was just about spectacular scenery. Then we began to understand habitat, and we expanded some parks to accommodate migration. Then species diversity became important, so we saved the Everglades. And now in some places we’ve created buffers by moving national forest land that borders a park from the Department of Agriculture to the NPS. I think you’re going to see more of that.

BP: All of these challenges–global warming, mining, Facebook, childhood obesity–what should backpackers do?

KB: I am deputizing you! I am an evangelist! I understand you’re in the choir, but you cannot just continue to go backpacking. You have to grab people at trailhead parking lots and let them know what awaits when they hike a bit farther in. You have to make converts.