Land of the Lost: Native American Artifacts in Utah's Range Creek

'Range Creek Pictographs'

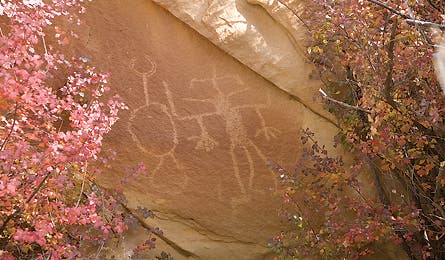

Range Creek Pictographs

Foundation of a Fremont dwelling

Mark Connolly (Right) and a fellow ranger

Trailside petroglyph

Rugged terrain surrounding Range Creek

thetrip6_0508_adamclark_445x260.jpg

Head ranger Mark Connolly

“I wouldn’t want some damned hippie digging me up and picking the gold teeth out of me after I die,” says Waldo Wilcox, 77, the longtime owner of a 4,350-acre tract of high-desert country that included part of Range Creek Canyon, a little-known Utah wilderness where I’m standing right now. “I wanted to leave this land the way it was, so I left all the dead Indians’ stuff alone.”

It’s an unorthodox land-management philosophy for a rancher (and vaguely insulting if you like Phish as much as I do), but that’s what has made Range Creek, 120 miles southeast of Salt Lake City, such a stunning place to explore. Mysterious petroglyphs line the canyon’s sepia-toned walls; they’re so precise and unblemished, it’s like they were etched in the rock yesterday. Cliff-side granaries are still stocked with dried corn. Visitors trip over grinding stones left by the Fremont, the native people who lived here and throughout Utah from 700 to 1400 AD, when they mysteriously disappeared. In fact, Range Creek is so well preserved that archaeologists have found intact sandals, woven baskets, and strands of ancient human hair. Standing here in the early November chill, I have the distinct feeling that the last 1,000 years never took place.

Waldo’s family had owned–and tightly guarded–this swath of high desert canyons and scrubby grazing land since the 1950s. But seven years ago, with little fanfare, Waldo sold the property for $2.5 million to the state of Utah. Old age was making it hard for him to run his cattle operation, and he wanted to retire. The agreement stipulated that the property, which is surrounded by 100,000 acres of BLM wilderness, would remain undeveloped (though Wilcox retains mineral rights). It also allowed the state to open the ranch, which encompasses 12 miles of the 50-mile-long Range Creek Canyon, to the public. That last part made national headlines because of the artifacts scattered across the terrain beyond the ranch’s gate. Many worried that looting was imminent. Fortunately, that hasn’t been the case, in large part because the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, which closely manages the area, permits no more than 28 visitors per day. Far fewer actually come–only 550 people a year have made the journey on average. It certainly helps that Range Creek is in the middle of nowhere.

My own trip involved a flight to Salt Lake City and a three-hour drive on an unlit highway into a land so remote I could only pick up one fuzzy radio station. (And it was playing “Honky Tonk Badonkadonk,” Trace Adkins’s ode to cowgirls with plus-sized cabooses.) The night was intensely quiet, so dark and billboard-less that I had to shout along with the music to keep myself from falling asleep.

When I finally passed East Carbon City, I turned off of UT 124 and read this sign: Warning. Range Creek is a primitive area. You must carry your own drinking water. There are no toilet facilities and no cell phone coverage at Range Creek. Proceed at your own risk. Perfect.

The next morning, I emerged into the biting autumn air, expecting to walk a circuitous path dodging ruins and pot shards. But I didn’t see anything other than dirt, clay, rock, and blue sky. Was I missing something? I was just starting to work myself into a panic when the sound of boots clomped out of the bushes. It was Mark Connolly, one of three conservation officers who watch over Range Creek.

I would soon discover that it’s impossible to roll over a metate, or leave a footprint, without a state employee taking note of you. Archaeologists who study Range Creek photograph, catalog, and sometimes collect relics for study, but they keep a precise record of where they found them–and they routinely put them right back. And they still find “surface relics” (things like arrowheads in the sand) on a regular basis. This is unheard of in nearby Fremont hotspots such as Nine Mile, near Price, Utah which was picked clean by sneak thieves years ago.

Most experts say the Fremont were a simpler people than other pre-Columbian tribes, like their famous neighbors to the south, the Anasazi, who lived in elaborate cliff dwellings and crafted fussy pottery. The Fremont hunted and farmed nomadically, ate out of grayware pottery, made clay figurines and buckskin moccasins, and holed up in pit dwellings when they weren’t on the move. In this canyon wedged between the Tavaputs Plateau and Green River, Utah, they raised corn, hunted bighorn sheep, and chiseled arcane petroglyphs on the sandstone walls. Their population peaked in 1050 AD at around 1,000. Then, over the next few centuries, they vanished, and no one knows for sure why.

Connolly, a youthful 55-year-old with a bushy mustache and a burnished tan, handed me a pair of binoculars. I scanned the hillside until my eyes came to rest on a granary, hanging from the cliff like a mud wasp’s nest. The seed repository was so high up, and so remote, that it remains untouched by European hands. Without 5.10 climbing skills, an archaeologist trying to reach it would probably break his neck. When I asked Connolly why anyone would build a grain-storage container on a near-vertical cliff, he mentioned rodent protection, then stated the obvious: These people were afraid of something more than mice. “They built these things 100 feet up so other humans couldn’t get their food,” he said. “They were trying to protect it from neighboring clans or, possibly, invading tribes.”

After another frozen night, I hiked onto the main road and set out on an 18-mile out-and-back that would take me into the heart of the property. I planned to explore several side canyons, then double back to the road, retracing my footsteps to basecamp. That’s another reason few people venture to Range Creek: Tenting in the canyon is off-limits, making for long (and repetitive) dayhikes.

Two miles from camp, beneath an overhang, I spot my first pictogram, the one Waldo Wilcox calls “the television screen.” It’s a huge, hand-painted drawing of a shield, high beneath a rock arch, with an anthropomorphic figure peeping from the center of the three-by-five-foot rectangle.

I stand for a while gaping, wondering what it could mean. There are no interpreters or books to guide your experience at Range Creek–and that’s one of its very best qualities. The imagination runs feral out here, and it gives the place a magical feel. You’re Indiana Jones. You’re John Wesley Powell. You’re exploring a wild slice of one of America’s most remote corners–a spot that virtually no one has seen since the last Fremont left a cracked jug here.

Two miles southeast of the shield, I turn off the main road to a singletrack path through Barton Canyon, which leads past brontosaurus-size rocks up towards the hulking Tavaputs Plateau. The trail branches into a maze of tilting pines and silvery sage filling the air with wafts of herbal medicine. One moment, I scramble through open desert, the next I follow the dry bones of a creekbed. And later, I wind through dense pine forests crisscrossed with so many animal tracks that I can’t identify them. My only tether to modernity is my GPS unit, which points me back toward the dirt road through Range Creek into Nelson Canyon.

Nelson is the most spectacular gallery in Range Creek. I spy a sun-disk petroglyph with 13 spokes, and two figures that look like warriors, with a lightning bolt passing between their heads. Maybe it means they’re empaths, able to feel each other’s pain. Maybe it’s a warning sign for intruders. In another, a ram leaps up a wall, exposing his fat belly to a hunter’s bow. Is this a prayer for food, or a prehistoric hunter’s way of showing off? Either way, the artist clearly likes to kill things. Then I come upon the Falling Man. He has a triangular head, his arms splayed out, legs pointed skyward like a tuning fork. Someone etched this figure at the bottom of a nasty drop just below a granary. Had someone shoved a corn burglar off the cliff face? I want to make sense of all these images, but I’m on my own.

Later, I call a few archaeologists, who each tell me something very cool: They have no answers. My hunches are as good as any. All theories are plausible in Range Creek–even the wild ones. In one last effort to figure these images out, I call Waldo. After all, the rancher has looked at them more than anybody.

“What do they mean?” he repeats. “Well, it all depends on how much imagination you got. I could tell you them people got off flying saucers, or that they got off of Noah’s Ark, and nobody could say that I’m wrong.”

PLAN IT

Range Creek, UT

The Way

From Salt Lake City, take I-15 south for 47 miles. Merge onto US 6 toward Price/Manti. Drive 83 miles to UT 123, turn east and cruise another 8.5 miles to UT 124. Head south for 8.8 miles until you reach an intersection. Go straight toward the brick buildings of the Horse Canyon Mine. Turn left at the Range Creek sign one mile past the mine buildings. Turn left and continue 8.9 miles on the unpaved winding road until you reach the North Gate camping area and the trailhead. Four wheel drive is recommended.

Camping

Designated campsites within the canyon are in the works, but for now it’s prohibited. For overnight forays, pitch your tent outside the North Gate.

Water

Some hikers filter water from Range Creek, but pack in your own (one gallon per person per day). This creek is downstream from cattle country.

Season

Spring and fall, with highs in the 60s and chilly nights, are primo.

Maps There are no official maps or guidebooks to Range Creek. Best bet: Pick up the USGS Lighthouse Canyon Quad ($6; store.usgs.com).

Permits

Required ($5 per person per day) and only available at Utah’s Division of Wildlife Resources website (wildlife.utah .gov/range_creek). For more information, call (435) 613-3700.