Hike Forever

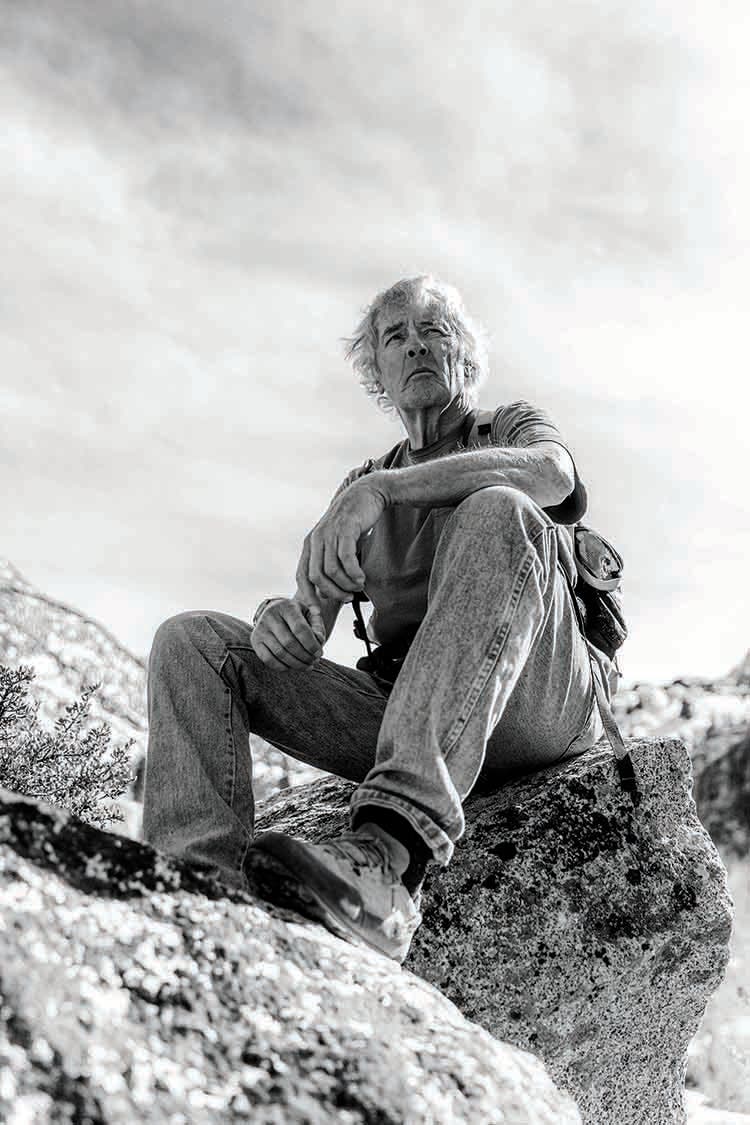

'Joe Kelsey. [portrait: Shaun Fenn Photography]'

Joe Kelsey. [portrait: Shaun Fenn Photography]

![Approaching Titcomb Basin Approaching Titcomb Basin, a favorite spot of Kelsey's. [photo: Ken Driese]](https://cdn.backpacker.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/approaching-titcomb-basin.jpg?width=3840&auto=webp&quality=75&fit=cover)

Approaching Titcomb Basin, a favorite spot of Kelsey’s. [photo: Ken Driese]

The author and Kelsey trading stories near camp in Indian Basin. [photo: Ken Driese]

Thanks to horse support, the author and Joe Kelsey carried only daypacks deep into the Wind River Range. [photo: Ken Driese]

“Now that I’m older, I seek out campsites with plenty of logs and rocks to sit on,” says Kelsey (foreground). [photo: Ken Driese]

Joe Kelsey was moving gracefully on granite. Long and lean, with meaty hands, he studied the rock before him and eyed the vertical face before deftly stepping up. Every move was precise, assured, unhurried. His weight balanced on his toes, Joe rose up the backcountry cliff with methodical ease. He never missed an essential foothold, never made an awkward move.

It was the first time Kelsey and I climbed together—at 11,000 feet in the heart of the Wind River Range in the heart of Wyoming—but we’d been corresponding for years. See, Kelsey is the keeper of records for these remote mountains. Almost every summer I hike into the Winds with a partner and put up a new climb on a granite wall (just as Kelsey himself did a quarter-century ago). We name the route, give a full description and date of ascent, draw a line on a photo, and send it all to Kelsey. “Indian Paintbrush,” 10 pitches, west face of Sacagawea; “Dark Side of the Moon,” 12 pitches, west face of Fremont; “Trepidation,” 9 pitches, unnamed tower northwest of Squaretop.

A climber and backcountry explorer by craft and a writer by temperament, Kelsey has been meticulously cataloging information about the Winds from alpinists, backpackers, fishermen, cowboys, and horsepackers for 40 years—often fact-checking it on the ground himself. Kelsey’s third edition of Climbing and Hiking in the Wind River Mountains, the local bible for backpackers and mountaineers alike, was published last year. He said he thinks it will be his last (19 years passed between the second and third editions; the first was published in 1981). No one else on earth has Kelsey’s knowledge of the Winds. The trails that are impassable due to deadfall, the lakes that still have indigenous brookies, the granite spires that remain unclimbed. If the measure of a man’s life is his lasting contribution to his community, Kelsey’s achievement can’t be underestimated: All those who care about the Winds, one of the greatest ranges in the world, owe him a debt of gratitude.

But none of this was on my mind that cobalt-blue day in the Winds a few years ago. Instead, I was captivated by Kelsey’s poise on the rock. In his 70s, he still moved with confidence—using skills that are gained over many years, and then often lost in the waning ones. It was while Kelsey was defying both gravity and age that I realized I would be him one day. Or at least, I hoped to be him. This wasn’t so much an intellectual cognition, but a visceral epiphany. I too will be old! For an instant, the 20-year age difference between us vanished and I inhabited the body of a 72-year-old, able to cheerfully accept a gradual but inevitable failure of the flesh. Yes, I will slow down, but I’m already old enough to know that style matters more than speed. I admired Kelsey’s unspoken pride at still having the motivation and the ability to do what he first did more than 50 years earlier. Would I be capable of the same? Most of us don’t think a lot about being old. We of course have aging relatives, but in our narcissistic way, we see them as different from us. Their past seems like ancient history, their present defined and boring, their future dreadfully limited—whereas naturally our own brief history is who we are, our present unique in the world and our future sure to be fantastic. I know as a youth, and probably almost until age 30, it was practically impossible for me to imagine myself as an old man. Even into my 30s, my invincible vigor and ego overwhelmed any thoughts of decrepitude—I climbed mountains, bicycled across continents, kayaked big rivers. By my 40s, I could see the outlines of who I might be in later life, but it remained too distant to be instructive—I kept behaving as if I were in my 30s.

It has only been in my 50s, when the exigency of the matter has appeared on my doorstep unbidden and unwelcome—back problems that required surgery, a wrist with arthritis, a surprising loss of strength at high altitude—that I suddenly feel what it will be like to be old. And it doesn’t feel so good. As my 79-year-old dad says, “Growing old ain’t for sissies.” Although much is made about the fear of death in our culture, I personally don’t carry this burden. I also harbor no desire to live as long as I possibly can. If you’ve attended the final years of any very old person, you know that life is not about quantity, but about quality. What matters is how you grow old. And it was on a trip into the Winds with Joe Kelsey that I found a blueprint.

On a cold morning in late August, photographer Ken Driese and I meet Kelsey and his two closest friends, Katy and Julia, at the 9,350-foot Elkhart Park trailhead near Pinedale. Katy and Julia are gorgeous blondes, playful and eager to get going, bounding down the trail ahead of us. Like so many mountain men before him, Kelsey is a loner, and Katy and Julia, his golden retrievers, are his constant companions. He tells tales about them as if they were his children, and he never goes anywhere, including deep into the Winds, without them (he’s had golden retrievers continuously since 1972). Our route into the high country follows the well-trodden Pole Creek/Seneca Lakes Trails. “I’ve hiked this trail dozens of times,” Kelsey says mid-stride, “but I never tire of it.”

Although Kelsey has curly gray hair and spiky black eyebrows, his legs are as brown and sinewy as someone half his age. It’s hard to imagine that he dreaded turning 40 and once felt like he’d “better get out there now, because next year I’ll be too old.” His stride is long and loping and when he’s not backpacking, he walks 4 miles a day with his dogs, to stay, he says, “barely fit enough for the mountains.”

On our first day (of five), we hike a solid 15 miles with 3,000 feet of elevation gain into Indian Basin—this is not a weekend destination. Despite the distance, Kelsey stops and talks to everyone we meet on the trail. He wants to know where they’ve been, what they’ve seen, which lakes are good for fishing this year, which passes still have snow. Normally almost taciturn, this is the writer in Kelsey at work—inquisitive and engaged, squirreling away bits of information.

Having hired packhorses to haul our climbing gear, our packs are light and we skim past Hobbs Lake, then Seneca, take Kelsey’s secret shortcut around Little Seneca, cruise by Island Lake, and make it to the glorious, sharp-toothed mouth of Titcomb Basin by nightfall.

The next morning, we dogleg east to explore Indian Basin, the vast morainal landscape between the gray massifs of Fremont and Ellingwood Peaks. We spend that day and the next scrambling through pika-chirping talus and verdant meadows, Kelsey regaling us with the lore of his beloved mountains. “You know that peak was named after Albert Ellingwood, one of the finest mountaineers of the 1920s. He made the first ascents of Warren, Turret, Helen, Sacagawea, and Knife Point, and, in 1926, soloed Ellingwood.” Kelsey maintains his history lesson while hopscotching across creeks and traversing ledges, as adapted to the terrain as a mountain goat.

On the third night, we gather around the roar of a camp stove, watching dusk descend like a sable curtain. Far below, the high plains disappear into the gloaming. Katy and Julia, mud-spattered and wet- dog stinky, curl up at Kelsey’s feet.

“I gotta have a campsite from which I can see a 100 miles,” he says. “I need the spaciousness. I don’t care what’s out there on the horizon, it just has to be a long ways away.”

As long as I promise not to tell anyone, Kelsey acknowledges that he’s originally from New Jersey. “My Dad was an insurance salesman,” he says, stirring innominate noodles, oblivious to the mosquitoes probing his leathered face. “Come home, sit in his chair, smoke cigarettes, and read Annapurna by Herzog or Americans on Everest by James Ramsey Ullman.”

Kelsey read these books too, but was even more inspired by backcountry meditations like Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, and Annie Dillards’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. When he started climbing himself, though, his father was aghast.

“‘It’s okay to read about it,’ he told me, ‘but not to do it!’”

In rebellious response, Kelsey became a member of the infamous Vulgarians, a clan of ’Gunks (Shawangunks, New York) climbers who were known for drinking hard and climbing bold.

“My mother told me to take up golf. ‘It’s something you can do when you get older,’ she said.”

He slurps down his noodles and growls, “I hate golf.”

Kelsey got a degree in chemical engineering from Cornell and almost had a Ph.D. in physics before discovering the Winds in 1969.

“I hiked over Jackass Pass with an 80-pound pack, awoke the first morning, stared out at all the gorgeous peaks, and thought, ‘This is it!’” Kelsey says.

“The Winds are all-encompassing. They have it all: perfect rock, lakes, couloirs, towers, flowers, elk, bighorn sheep, trout…” His scratchy voice drifts off at the wonder of it.

The next year Kelsey moved to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where he bought a cabin with no electricity and no running water. Forty-two years later, it still has neither, and Kelsey still lives there half the year, spending the cold part in Bishop, California, wandering the Sierra. For 20 years, Kelsey worked as a guide for Exum in the summer and labored indoors in Berkeley, California, through the winter as a technical writer. He still speaks fondly of the guiding.

“There were then only 15 of us guides, and we were a band of brothers,” he recounts wistfully. They climbed the peaks with pitons and fished in the creeks with tent cord for line, safety pins for hooks, freeze-dried corn for bait. “The camaraderie ran deep,” Kelsey says, standing up and walking off toward his tent.

The next morning, we’re up before the sun, hovering around our purring stoves. The air is cool violet and there are no clouds, not a one. They wouldn’t dare mar the magnificent pageant of color—pink to yellow to white to blue. We can already tell it’s going to be one of those irreplaceable days.

We load our packs with ropes and gear and tramp up through a narrow cleft at the base of Elephant Head, an 800-foot granite buttress. Kelsey thinks he remembers, out of the thousands of acres he’s reconnoitered, a nice set of apartment-size boulders for climbing. And sure enough.

“Au pied de l’éléphant,” proclaims Kelsey as we halt among giant toes of granite. Although he quit guiding in his late 60s—“when the clients became faster than I was,”—he’s still game for old-fashioned cragging. We flake the ropes, rack up, and pull on rock shoes.

Now you might think a man in his 70s might be a little creaky for hard climbing, but not Kelsey. He moves upward like a dancer. Of course, he’s not the only senior hiker to remain physically fit at an age when most people are looking at photo albums, not making them. Heck, Earl Shaffer, the Appalachian Trail’s first thru-hiker, trekked it for the third time at age 79. But unlike record-setters, whose feats can appear unattainable for us mortals, Kelsey’s path seems like one I can follow: Keep doing what you love. Go for a short hike if you can’t go for a long one. Use packhorses if you’d rather spend your energy climbing backcountry rocks than carrying a heavy load.

At lunch we lie in the meadow, close our eyes and swap stories. This is the finest gift of the mountains: to be utterly unattached to the outside world. We are in an alpine meadow so close to the sky we need only reach out our arms to touch it—while the rest of humanity is far down below, entangled in a morass of emails and tweets and text messages. The spiritual freedom of this recognition gradually fills us like a snowfield fills a tarn. For a while we simply listen to the exquisiteness of nothingness, allowing ourselves to be absorbed into the landscape, to become part of the mountain like the purple fleabane and the flecks of feldspar.

I am dozing, in a dream-like state but still conscious of the warm rock under me and the sun upon my skin, when I once again fast forward to inhabit the body and mind of my older self. I can see that I will enjoy what I presently still resist: taking my time, observing more than doing, accepting limitations. I can imagine no longer constantly pushing, but rather accepting the world for what it is rather than what it should be, and myself, not for what I will become, but for what I already am.

After a three-hour siesta, we rally for one last climb.

Our objective: a well-featured crack that provides Kelsey the opportunity to use all the maneuvers stored in his muscle memory. Hand jam and high step, counterbalance, constancy, fluidity. From the side he appears to be climbing right into the sky, as if at the top of the rock wall he might step out onto a cloud.

Pulling onto the summit, Kelsey looks at me with his hazel eyes, pushes back his mop of gray hair, and says simply: “This is a great life.”

Mark Jenkins wrote about Tibet’s unclimbed mountains in January 2013.