A Father, His Sons, And The Trail

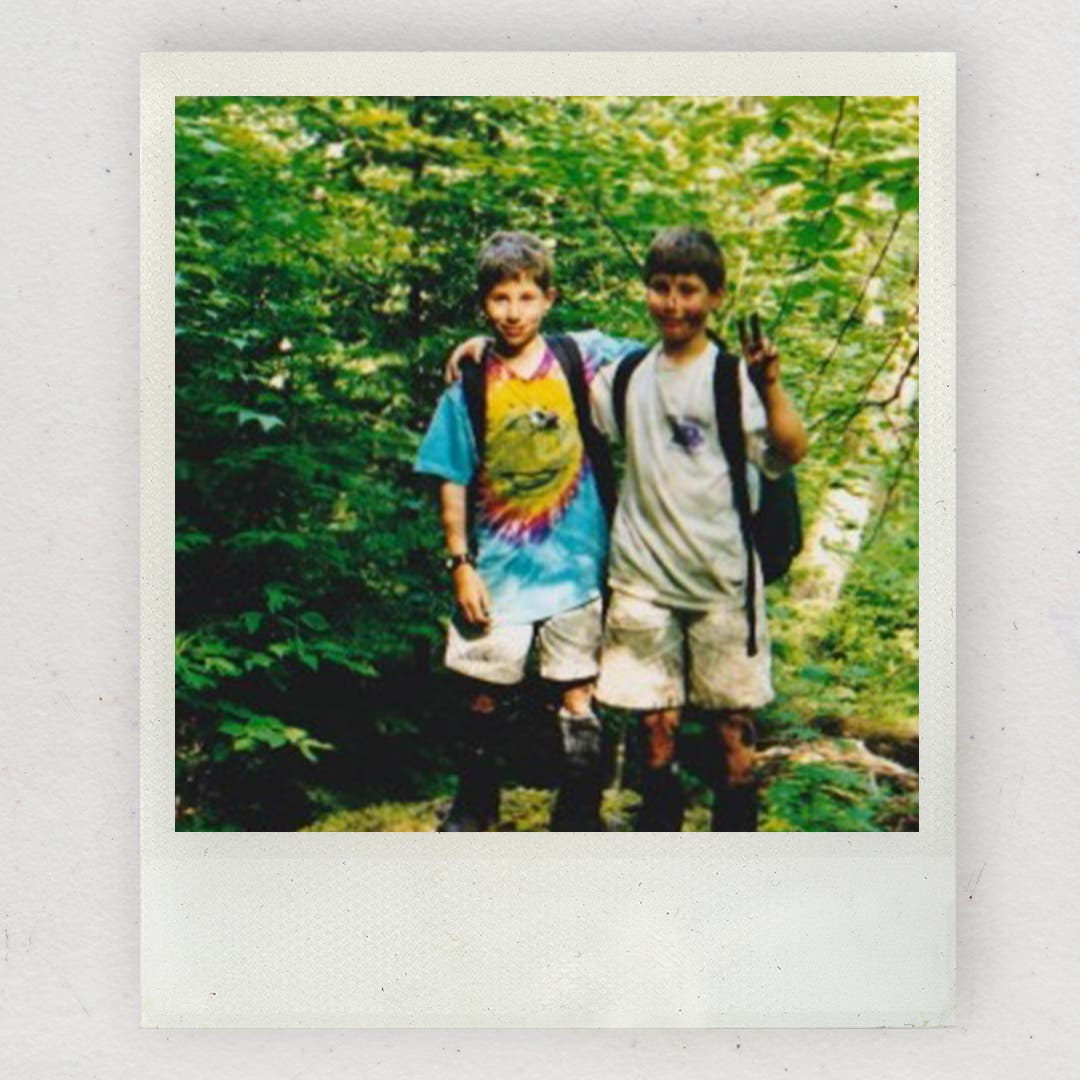

The author (far left and far right), his dad, and his brother Simon through the years (Photo: Eli Bernstein)

Hiking isn’t just what we do—it’s who we are. If that sounds like you, go deeper with Outside+, our all-access pass to the best of Backpacker. Members get to read all of our stories, including tales from the trail, recipes, our full-length gear reviews, trip reports complete with interactive maps, and more. Plus, you’ll get access to our print edition, workout plans, exclusive events, and access to our sibling titles like Climbing, Yoga Journal, Ski, and more. Sign up today.

The Adirondacks guard their treasures. The summits in this sprawling granite massif in upstate New York are defended by grabby phalanxes of Balsam fir, gaiter-eating bogs, and water-slicked rock-and-root staircases. Adirondack views are hard-earned and frequently showstopping when they present themselves; they’re also far from a guarantee, and I’ve been skunked by obscuring branches or porridge-thick cloud cover too many times to count. Rocky Peak Ridge, however, was proving to be an exception. I was hiking with my dad and younger brother Simon, and starting from the summit of aptly named Bald Peak a few miles to the east we were treated to spinaround vistas of the park’s rumpled northeast landscape, with the crowded buttresses of the High Peaks poking up to the west. (In typical Adirondack fashion, these views were temporarily wiped from our minds by 1,000 feet of high-grade ascent up a notch in the ridge.)

As we neared the summit, though, my mind remained fixed on what I was going to say to my dad at the top, not on the scenery. This was better than the alternative, which was focusing on my leaden legs and sore feet; over the two days prior we’d knocked off five peaks over 26 twisting, muddy, steep miles. (To those hiking out west: You don’t know how good you have it.) While I’d found a way to push through the fatigue, this mental stumbling block remained: How would I express my gratitude to the man who’d made me the hiker—and the person—I am today?

When I was 17, I quit hiking. In my dad’s meticulous notes, the ones he wrote to document our every trip to the Adirondacks, the occasion only merits a single line: “August 24-27, 2006. Mitchell Bernstein, solo (Eli and Simon back out night before trip).” The next four paragraphs are devoted to his usual shorthand recording of excursions: his hike up MacNaughton Mountain (he met Ron from Troy on top, and then got lost for over an hour on the bushwhack down), a difficult march over Indian Pass, and an ascent of 4,360-foot Mt. Marshall. On the five-hour ride back to our house in the suburbs outside New York City, he enjoyed a radio program about “Louie Louie.” Simon and I got less ink than the return drive.

By the time of our betrayal, my brother and I had been questing with my dad to hike every Adirondack 46er—the 46 peaks in the park over 4,000 feet—for seven years. He’d climbed Mt. Marcy, the range’s pinnacle, with his brother when he was 20, and had wanted to go back and tackle the rest ever since. So, beginning when I was 10, we’d traipse into the woods a couple times every summer and emerge a few days later, covered in bug bites and full of stories about bottomless mud pits, newt sightings, and the peaks we’d ticked off. These trips became our strongest bond, something to look forward to during the school year and then reminisce about after we returned. Simon and I tagged along without question. We enjoyed the food at the Silo in Queensbury on the drive up and Pitkin’s in Schroon Lake on the way home, and backpacking was simply part of our yearly routine. Until it wasn’t.

I was a difficult teenager, clashing with my parents over the usual stuff (curfews, responsibilities, independence) but with a rancor that brought tension, occasional tears, and plenty of weekends spent grounded. To this day, I don’t remember if quitting on my dad was my way of getting back at him for something, but I convinced Simon to join my mutiny. We had killed the dream of becoming Bernstein 46ers together. I didn’t know, until my mom told me years later, that backing out on the trip crushed my dad. He never let on that we’d wounded him. We Bernstein men are not an outwardly emotional bunch, at least not with each other. While I’ll lose my mind over a half-decent view, a marmot sighting, even a rad-looking tree, I’ve only told my brother and my father that I loved them once each over the past decade. (Simon’s came in an alcohol-aided text. I didn’t get a response, and the incident has not been brought up since.) This is not to say we don’t have a tight bond, just that we express affection in other ways: skiing, watching baseball, and, most of all, hiking in a root-skeined, boulder-strewn blanket of mountains in upstate New York, together.

Like a lot of teenagers, I calmed down (a bit) in college. I still had no desire to hike, but my relationship with my parents improved. During those four years, Simon, my dad, and I discovered a shared love of skiing. On trips to Vermont, Colorado, and British Columbia we found a new common language, this one written in snow instead of mud. Slowly, I began to appreciate the outdoors—and time with my family—anew.

I’m not sure who put forward the idea to begin bagging 46ers again. If it was me, I’m sure my dad was surprised, and vice versa. Nonetheless, in September 2011—five years after I quit—we all headed upstate. According to my dad’s notes we ate lunch at the Silo on the way up, dined at Pitkin’s on the drive home, and in between summited Whiteface and Esther in a downpour. At one point on the hike up we took shelter beneath an emergency blanket because it was raining so hard. It was, in short, a perfect reintroduction to Adirondack hiking. The quest was back on.

Whiteface and Esther were 46ers number 34 and 35 for Simon and myself, but 42 and 43 for my dad, who had been taking trips to the park on his own. He decided to backtrack and get those handful again with his sons, as we had always intended.

The next couple of years saw us advance toward our goal in fits and starts. I remember that most of our trips during this time involved awful weather and one of us getting injured at some point. By 2013 we hadn’t made much more progress: Simon and I had 38 under our belts after a trip in October of that year (“very slippery” my dad’s notes pithily read after a wrong turn on Allen Mountain had us beating back tree branches and blindly searching for the summit trail).

Then, another five-year hiatus, but this time for a less antagonistic reason. The resumption of our 46er journey had reignited my love of hiking. Rather than viewing the trail as something to merely complete, a tiring and sweaty means to an end, I now saw it as the place where I could be my truest self and connect best with the people I hiked with. I began to travel farther afield in search of adventure, and the mountains in Switzerland and Peru and Nepal made the Adirondacks look, well, less appealing. Simon and I were now working full-time, and vacation days were harder to come by. Given the choice between driving upstate and going somewhere I’d never been to hike with friends, I chose the latter. My dad was always excited to hear about my adventures, but I knew that the ’Dacks were still on his mind.

I moved to Colorado when I accepted a job at Backpacker in 2017. It was thrilling to explore my new state and its mountains. Simon and my dad came out to hike and ski, and I reveled in a life that now literally revolved around putting one foot in front of the other on the trail.

At some point—probably on a trip into the Rockies—I finally realized I would have none of this if not for those formative trips to the Adirondacks. And my dad. So, in 2018 I came back to New York for a week and we all notched MacNoughton and Marshall (the second time each, for my dad) as well as Tabletop for number 40. The next time I returned to the Adirondacks was in the summer of 2020, to finish the job.

And suddenly, we were almost done. The final hump to the top of Rocky Peak Ridge stood before us, just a few more granite slabs. This peak, the 20th-highest in the Adirondacks, was the long-awaited number 46 on the Bernstein list, chosen both for its views and relative isolation. My mind ping-ponged between relief—I was inwardly talking to my legs at this point, begging them to get up just this one last bit—and uncertainty: How was I going to make this moment count?

Part of me wanted to express what I’d been thinking about for the past few years—that I owed my career, and lifelong memories, and a lot of the joy in my life to a dad that made sure I experienced the outdoors from a young age. That part of me wanted to tell him I loved him not just for that, but for being my dad. For forgiving Simon and I when we were ungrateful teenagers. For supporting me as I blazed my own path. For taking us back to the Adirondacks. For too many reasons to list here.

Instead, I said nothing. I whooped, and hugged my hiking-partners-by-blood, and Simon and I popped mini bottles of champagne we’d brought along for the occasion. I thanked my dad for the chance to achieve this dream, one that was now old enough to drink the champagne with us. But I didn’t say “I love you.” In my mind it was implied, as much a part of the scene as the views out to Giant Mountain’s slides in the east and over Lake Champlain to the west. That love—for my dad, for my brother, for the hundreds of miles of hard hiking it’d taken to get to this point—was as entwined with the Adirondacks as its uncountable, hiker-tripping roots. This moment was love, and I know he knows that, too.

The final notation from my dad doesn’t mention the completion of our 46er quest. It merely includes two exclamation points after our summit time of 11:14 a.m., and then adds, “Great hike; great views.”

I’d only add one thing: great company. The best, in fact.