Depth Perception: Trek to Grand Canyon's Royal Arch

'Take Angels Window Trail for this view (David H. Collier)'

Take Angels Window Trail for this view (David H. Collier)

Pools along Royal Arch Creek (Elias Butler)

Skirting the Esplanade (Elias Butler)

Royal Arch (Elias Butler)

The gust that slams us is so violent, for a second I can’t tell if we’re at the front end of a flash flood or in the path of a wayward jet.

I’d heard it coming from miles away, a furious roar that peeled off the South Rim, ripping through piñon junipers and plunging down the 1,000-foot-deep chasm of Royal Arch Creek. When it finally blasts us, bending our tent poles and flattening the nylon against our faces, I experience a briefly suffocating reminder of the Grand Canyon’s raw power. Yet strangely, in the momentary disorientation of impact, I feel calm–happy, even–to be in this place. Even the presence of my 11-year-old son, Austin, doesn’t make me rethink my decision to forge on, despite ominous rain clouds and the crushing gusts. After 15 years of scheming, nothing is going to stop me from getting to Royal Arch.

I’ve hiked every trail and established route off the canyon’s South Rim, but I’ve never made it to the Arch. Considered the Hope Diamond of canyon treasures, the largest natural bridge in the park lies amid a flotilla of buttes and spires in the Aztec Amphitheater in the remote central part of the canyon. Just getting to the trailhead involves a brain-rattling drive on a 35-mile-long jeep road. Then it’s 14 miles of expert-level backpacking across an obstacle course of scree slopes and greasy pour-offs.

Those challenges, plus the usual workaday stuff–raising Austin, caring for dying parents, juggling two jobs–had conspired to keep me away. But in October, when Austin hiked the difficult New Hance Trail, I decided he was ready to accompany me to Royal Arch. In November, the plan was set. We would follow a route first charted by Harvey Butchart. From the mid-1940s to the 1980s, Butchart pioneered hundreds of off-trail routes. His discovery of Royal Arch, in 1959, made him an instant guru among Grand Canyon groupies, who later snapped up his guidebooks, Grand Canyon Treks, I, II, and III.

Of course, Butchart’s fanaticism came at a cost: In his quest to explore every inch of the canyon, he all but abandoned his family. Knowing this, my solution for years has been to bring the family along. Austin made his first trek into the canyon before his fifth birthday, and has spent 75 nights below the rim. But I still have some trepidation. On this hike, we’re tackling technical, canyoneering-style difficulties. If Austin breaks a leg or becomes hypothermic, it could take up to three days to get help. He’s comfortable with Grand Canyon terrain, but as the wind kicks up again, sending rocks clattering, I wonder: Have I become so focused on my own checklist that I’d put my son at risk?

“Do you think it’s safe?” asks Austin, pausing in the middle of a scree slope on the Esplanade. It’s the first day of our trip. We’d driven four hours through the Havasupai Indian Reservation and Kaibab National Forest to one of the least-visited trailheads on the South Rim, then descended two knee-crushing miles to this boulder-strewn plateau. Navigating Chemehuevi, Toltec, and Montezuma Points, we’d seen soaring ravens and sign of bighorn sheep. Now we’re picking our way through a rockslide that falls at a dizzying pitch for 500 feet.

Out in front, and testing for stability, is my friend and Flagstaff photographer Elias Butler. Along with Flagstaff physician Tom Myers, Butler co-authored a recent Butchart biography called Grand Obsession. During their research, they retraced a dozen of Butchart’s most technical routes, but neither touched the 12,000 miles and 1,025 days Butchart hiked during his 42-year exploration.

As Butler points out loose rocks to Austin, I think about the trek we’re undertaking. Like many Grand Canyon hikes, the Royal Arch loop is a quintessential Grand Canyon “route,” which should not be confused with the corridor trails frequented by 90 percent of Canyon hikers. Cairns, as opposed to signs, sporadically mark the way, and water is reliably found in only three places along the entire 34-mile loop. A trail like this could thwart an inexperienced hiker, but not my son. He did his first rim-to-river hike at four, and seven years later confidently billygoats across scree slopes where one slip could result in a serious injury.

Pleased by his growing surety, I focus on the ivory tower of Mt. Huethawali lit up in the afternoon light. We walk another two miles, then camp on the tip of the Esplanade, pitching our tents and eating dinner under shooting stars. Digging into my pasta, I finally answer Austin’s question: “I think it’s more dangerous to drive the freeway in Phoenix than hike anywhere down here.”

On day two, we drop into the eastern arm of Royal Arch Creek, trading big canyon panoramas for an ever-deepening gorge. Butler and I are relieved by Austin’s progress. Even with his experience, off-trail canyon hiking for an 11-year-old is a far cry from Butchart’s “fast and light” method.

Butchart carried only a knapsack, sleeping bag, food, and canteen. With no tent or family, he averaged 12 hard, cross-country miles per day. We’ve hiked a scant eight since our start–most of it in the relentlessly rocky drainages atop the Esplanade. Dropping onto the scoured slickrock floor of Royal Arch Creek, I momentarily envy Butchart’s approach. Austin is cranky, and I’m tired from carrying gear and food for two–plus the emotional weight of worrying about my child’s safety and happiness.

Fortunately, relief is in sight. By late afternoon, we reach a cluster of potholes, the first reliable water source on the trek and an oasis by Grand Canyon standards. Despite little rain in recent months, the pools are four feet deep and flickering with insects. We climb onto a slickrock bench and pitch our tents. Then Butler spies an ancient pottery shard half-hidden in the red dust.

As quickly as it gathered, Austin’s cloud lifts. Whatever irritation he has carried visibly vaporizes–erased by the discovery of this prehistoric relic. Watching him trace figures in the sand, I’m reminded of a major difference between Harvey Butchart and me: Butchart never included his family in his discoveries, while I am bringing Austin to ones he will never forget.

“What would Harvey do?” Butler half jokes as we survey the ominous skies around us. It’s the third day of our trip, and we’re now just six miles from Royal Arch. Despite the gathering clouds, we eat breakfast on a ledge overlooking the potholes, then decide that rather than lumber with heavy packs to the Arch, we’ll leave our camp and dayhike–basically, make a run for it and retreat if the weather turns.

Although our route mainly follows the creekbed, it is not exactly an easy, rock-hopping ramble. The first–and biggest–obstacle comes just below camp, when we encounter a sheer 100-foot pour-off. We take a bypass, climbing up a steep talus slope and crawling through a dwarf-size opening between a juniper trunk and the cliff face, then slide down a jumble of boulders to the drainage floor.

The 2,000-foot-deep gorge gets warmer and lusher as we descend. First the prickly pear appears, then the ferns, monkey flowers, and glassy pools. When Butchart hiked this drainage 50 years ago, he suspected that he was coming upon something special. He had no idea he was about to discover Shangri-La.

My heart rate increases as we round one bend after another, the canyon closing in and seeming softer, now laced in the coral-like calcium carbonate deposits called travertine. Then, out of nowhere: the Arch, suspended 100 feet above the canyon floor. As if to reward us for our effort, the clouds part, illuminating it in vibrant sunlight. Standing under the bridge, Austin beams with pride and I do too, almost to the point of tears. Despite the everyday obstacles that threatened my journey, I made it. And sharing this reward with my son is sweeter than anything.

But I quickly sober up. This is no triumph if we don’t make it back to the car. And there is no hazard more threatening to obsessed Grand Canyon hikers than their own inflated egos.

As we turn to leave, Butler points to an area on top of Royal Arch where a helicopter landed in 1963 to rescue Butchart after he slipped over a pour-off and broke his heel. Others have died near here, including George Mancuso, Butchart’s heir apparent in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2001, he was killed in a flash flood while exploring a creek during summer monsoon season.

Abruptly, a rainstorm arrives, and we beeline to camp, scampering up pour-offs that have become increasingly slippery. With each backslide, Austin and I gouge our shins. The shower turns into a downpour, and the temperature drops 20 degrees. Austin is scared, fighting tears and hiking as hard as he can. Following closely behind him, I grow angry with myself. These kinds of situations are precisely why Butchart left his family at home and why many of my friends–parents who’d rather spend weekends with their children–have given up ambitious backpacking trips.

Then, as often happens in the canyon, the darkness lifts again. We climb onto a ledge, now speckled with freshly filled potholes, and see our tents; we’ve made it back from the Arch in half the time it took to get there. In the last gasp of sunset, the clouds part, and a double rainbow frames our camp.

On our last night, I stay up and study the sky. To the southwest, the twinkling orbs of Jupiter and Venus are almost aligned for the first time in 40 years. A half moon shines blue amid the many stars, casting the craggy cliffs in an eerie silhouette.

We have a big hike tomorrow, but I know the hardest terrain is behind us. Back from our adventure, Butler and Myers will check off a commemorative Butchart route that involves a scary free-climb to the top of the Cheops Plateau. I’ll secure a permit to return to Royal Arch. And Austin will write a school essay in which he says Grand Canyon backpacking is his favorite sport.

Somewhere between the South Rim and our campsite on Royal Arch Creek, a boulder breaks off the canyon wall and crashes through the gorge. The sound reverberates for several seconds, and I tense for a moment as the echo grows, then fades.

Standing in the moonlight, I am struck by the fragility of Austin, me, this. But then–just like my anxiety on the descent to Royal Arch–the feeling passes and I’m left with a deeper calm, like a pilgrim returning home from a successful journey.

Royal Arch: The Perfect Loop

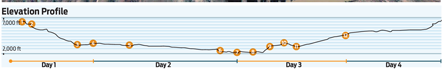

Pack two days’ worth of water and dive into the heart of Harvey Butchart country on this 4- or 5-day, 34-mile trip.

Hike It

The author’s route went straight to Royal Arch and back, but this loop packs in more canyons and cliffs, plus a 20-foot technical rock climb on day three. Starting at the South Bass trailhead (1, see below), descend 1.2 miles north to a three-way junction to begin a counterclockwise loop. Go straight on South Bass Trail (2) and drop into Bass Canyon, descending more than 2,000 feet in 2.5 miles between two towering sandstone buttes that pinch the gorge tight. Bear left onto the Tonto Trail (3) and go 1.5 miles to a plateau campsite (4) under the 4,800-foot red walls of Tyndall Dome.

Start day two by 8 a.m. to avoid the midday scorch–it’s 11.5 miles to a primo campsite on the Colorado River, the trip’s first dependable water source. Follow the Tonto Trail west to the bottom of Copper Canyon (5), where you might find water in potholes after a rain. The route veers around 4,700-foot Fiske Butte and traces sheer sandstone cliffs above Walthenberg Rapids, which roar through Granite Gorge. After 10 miles, the Tonto Trail ends in Garnet Canyon (6). Head west on an unmaintained trail dotted with cairns. End at the sandy banks of Toltec Beach (7), your second camp at mile 17.5. On day three, leave your pack at camp for a 2.1-mile out-and-back to Elves Chasm (8), a secluded, waterfall-rich grotto at the mouth of Royal Arch Creek. Backtrack to camp and lay over or finish the day’s remaining six miles with a stiff ascent to a roughly 20-foot rock wall and the technical crux of the trip (9).

Pack a harness, 40-foot dynamic rope, locking carabiner, and 20 feet of webbing for belays and for hauling up packs. From the top of the cliff, the route climbs gradually for 1.7 miles before dropping into Royal Arch Creek (10). Then, descend the rocky creekbed to Royal Arch (11), the Grand Canyon’s largest natural rock bridge (there’s a reliable spring upstream of it). Hike back upstream 3.2 miles to a set of smooth potholes carved into the creekbed, and your last campsite (12). The final day ascends past Montezuma, Toltec, and Chemehuevi Points. After 7.3 miles, reconnect with the South Bass Trail and climb 1,200 feet to your starting point.

The Way

To reach the South Bass trailhead, go west from Tusayan six miles on FR 328 (off of AZ 64). Veer northwest onto FR 328A for another 17.6 miles to Pasture Wash Road. Turn right and continue to the parking lot.

When to Go

Spring, when water is plentiful, or fall. Summer brings heat and flash floods.

Go Guided

Join the Grand Canyon Field Institute on an eight-day trip to Royal Arch in April 2010. Food and shuttle included. $665; grandcanyonassociation.org/gcfi

Guidebooks and Map

Official Guide to Hiking Grand Canyon, by Scott Thybony ($12, grandcanyonassociation.org); Grand Canyon Treks, by Harvey Butchart ($17, spotteddogpress

.com); National Geographic Grand Canyon National Park map ($12, natgeomaps.com)

Permits

Required backcountry permits are $10, plus $5 per person per day. Apply up to four months before desired departure date. Download application at nps.gov/grca/planyourvisit/backcountry-permit.htm; then fax to (928) 638-2125. Entrance: $25 per vehicle.

Vacation Planner

Get hotel, restaurant, and great travel beta at mygrandcanyonpark.com.