Ranger Randy Morgenson's Epitaph in the Sky

'John Dittli'

We were on a cross-country route, ascending a gentle gully, when Rick Sanger—or “Ranger Rick,” as he was known for nearly two decades in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks—bolted past me in a full sprint. His elbows were pumping, his boots were kicking up gravel, and the hiking pole in his right hand was pointed skyward, gripped in the manner that one might wield a sword while charging an enemy—or hightailing it away from one.

Startled, I glanced over my shoulder to see if I should be running too. But there was nothing behind us with claws or fangs, only granite and a few old burled snags, their haunting but harmless limbs reaching up into the lingering edge of an afternoon thunderstorm.

I turned to face uphill again and watched as Rick, in full stride, charged up the rock-strewn gully. He moved not with the clumsy, bouncing gait you’d expect from a man running uphill with a 30-pound backpack, but rather with the flowing rhythm and grace of something freakish, like a genetic blend of mountain goat and ninja.

I scanned the landscape ahead, searching for whatever had precipitated this bizarre behavior, and a metallic glint caught my eye. It was 30 or 40 yards ahead of Rick, up near the top of the slope and drifting toward him across a ridge that converged with the gully we were climbing. It was to that intersection he ran, leaped, and, with a veritable battle cry, brought his hiking pole down upon a bouquet of balloons riding the air currents. He pinned the shiny mylar to the gravelly soil, his chest heaving as he caught his breath.

I reached him just in time for the coup de grâce, a fatal downward stab with his hiking pole, both hands on the “hilt” just for effect. “That was for Randy,” he said with a grin as he picked up the deflated mass and shoved it in the side pocket of his pack.

Randy Morgenson had been not only a legendary wilderness ranger in these mountains, but a personal friend and mentor to Rick. Their mutual disdain for garbage—dubbed “backpacker detritus” by Morgenson—came from hauling gunny-sacks full of it out of the back-country. Balloons were, and still remain, a sore point with rangers. The flying garbage ends up anywhere and everywhere, usually crumpled on the windward slopes of the higher peaks or tangled among the branches of whatever cedar, pine, or willow stands in its flight path when the helium runs out. The metallic versions, like this one, flash relentlessly like signal mirrors. “They intrude upon the most sacred places with their banal messages,” Rick said. “To catch one in the act and hack it down is a dream come true.”

When the adrenaline subsided, and we stopped laughing, I felt a presence, a silent observer to our antics. Rick’s efforts had brought us into view of our trip’s objective—Mt. Morgenson.

The 13,920-foot, southern Sierra peak is unofficially named after the esteemed Sequoia and Kings Canyon backcountry ranger who had, over the course of more than 30 years of service, become as famous for the volume of garbage he lugged out of the mountains as he was for his wilderness stewardship, gentle kindness, and an uncanny ability to find lost or missing hikers and climbers. Which explains why the ranger community was shocked when, in July of 1996, Randy Morgenson himself went missing.

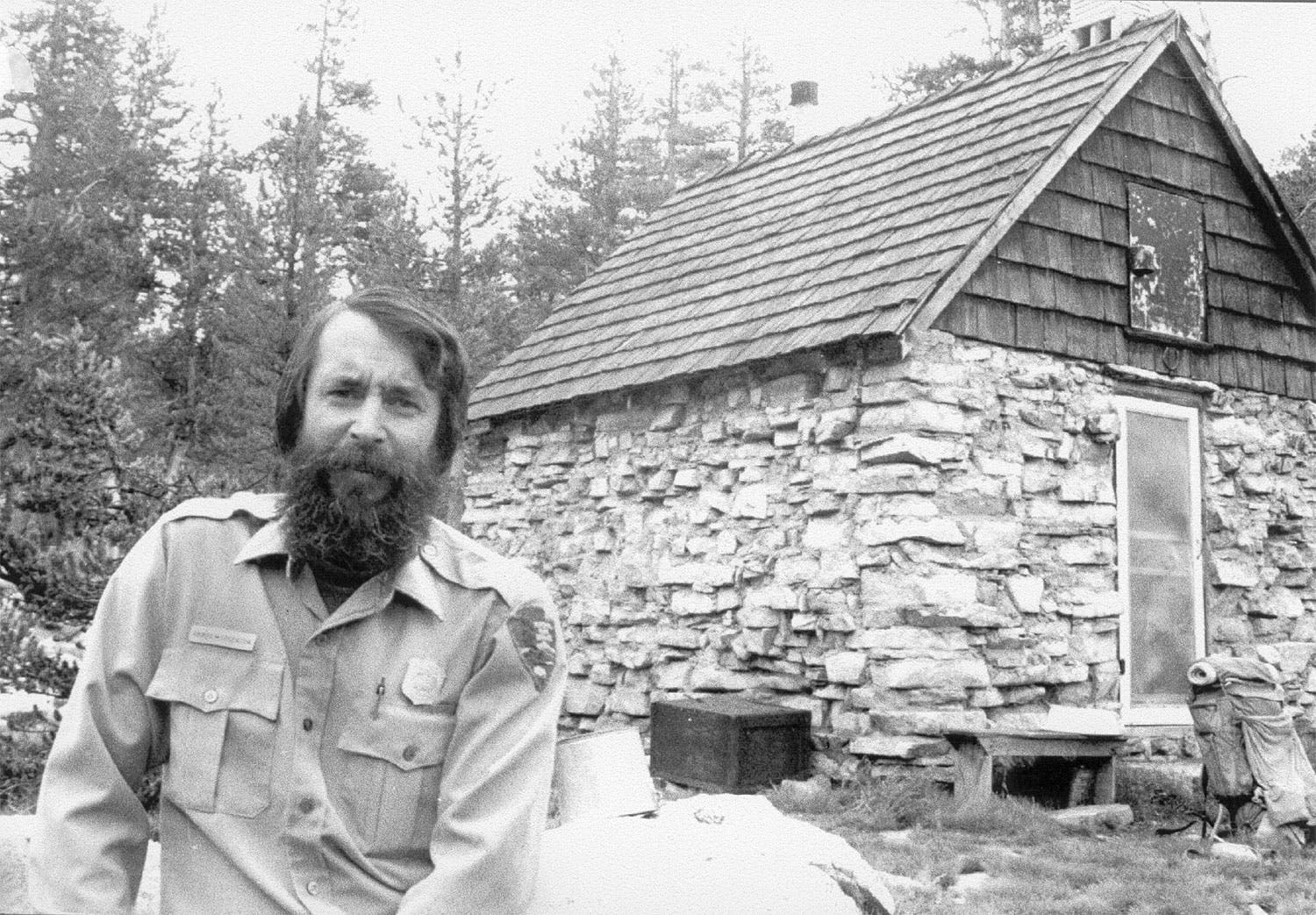

That summer, Rick was a just a second-year backcountry ranger and considered Randy the wisest man in these mountains. When Randy failed to check in by radio for several days, Rick hiked through the night to his mentor’s duty station at Bench Lake (above) and discovered a note confirming he was overdue from a cross-country patrol. It spurred one of the most intense and emotionally draining search-and-rescue operations in National Park Service history, in large part because the rangers were searching for one of their own. Thirteen days later, the official search, which included helicopters, dog teams, and dozens upon dozens of volunteers, was called off. Not a single trace of Randy had been found, not even a footprint.

I followed the disappearance from day one, having heard about it from Randy’s former boss, retired ranger Alden Nash, who was a family friend of mine. He told me that Randy had grown up in Yosemite National Park, carried around Ansel Adams’s tripod as a boy, and spent more time in the Sierra than John Muir himself. But he was also human and had his flaws, his personal demons. The summer he disappeared, his wife had served him with divorce papers. And those closest to him said he had seemed depressed. It all fueled speculation about his fate. Perhaps he went missing on purpose—walked out of the wilderness to start a new life elsewhere. Or maybe he’d ended the one he had in some wild and remote corner of his beloved Sierra. He’d also had run-ins with a climber and a horsepacker the previous year, so foul play wasn’t off the table, either.

In the years that followed the search, Alden and I made repeated trips to the mountains in search of clues to solve the mystery of Randy’s disappearance. I never knew Randy, but I was obsessed with his story. Could a man with his experience really just vanish?

It wasn’t until the summer of 2001, five years after he disappeared, that Randy’s remains were finally discovered. A 19-year-old member of a California Conservation Corps trail-building crew ventured off-trail and found his body at the base of a waterfall. (After comparing records and GPS coordinates from search teams, I realized this ravine had been inadvertently skipped by just a few hundred yards.) The following summer, Alden and I retraced Randy’s presumed final cross-country patrol from his last-known whereabouts at Bench Lake to where his remains were found in the gorge above Window Peak Lake. On the route, Alden and I detoured slightly and scrambled up Arrow Peak—as we had many peaks over the years—to see if Randy had signed the summit register.

He had not, but as we were sitting there atop the peak, Alden pointed toward a hazy and distant grouping of mountains to the southeast. “There’s a Fourteener over there near Mt. Whitney that’s never been named,” he told me. “People are starting to call it Mt. Morgenson to honor Randy.”

“Do you know who named it?” I asked.

“I can’t say,” he replied.

“As in you don’t know?” I clarified, “or you can’t say?”

“Yes,” he responded.

I suspected it had been rangers, so Alden’s reticence didn’t surprise me. Rangers protect their own, and naming a peak, even unofficially, might be construed as a rogue action by their bosses. Seasonal backcountry rangers have no long-term security—they’re hired and fired annually—so they can be anxious about jeopardizing their coveted jobs. Better to keep quiet than risk losing their place in the wilderness.

Thus my journey to climb Mt. Morgenson began as a riddle. Like Randy’s disappearance, the peak’s exact location (and who named it) was at first a mystery. “It’s hard to find a mountain that’s not there,” Alden told me as we speculated over a topo map that evening in camp, below Arrow Peak. Not long after that 2002 trip, I received an envelope in the mail that contained a topo map with an “X” marking the spot; the attached note clarified that the name Mt. Morgenson was being unofficially suggested by Randy’s fellow backcountry rangers and other park employees in his honor.

In The Last Season, the 2006 book I wrote about Randy and his disappearance, I described Mt. Morgenson as “. . . the first peak west of Mt. Russell and just north of Mt. Whitney, a high and wild granite monolith of [nearly] 14,000 feet that was somehow overlooked all these years. The name can’t be found on a map—the U.S. Geological Survey and Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks don’t officially recognize the title. ‘You can’t Google it,’ said one ranger [back in 2006], ‘but you can climb it.’ And really that’s all that matters.”

Shortly after the book’s publication—and a decade before my own attempt to climb the peak—a summit register bearing the name “Mount Randy Morgenson, 13,920’” was hauled to the top by two park veterans. A peakbagger named Richard Piotrowski found the original register missing when he climbed Mt. Morgenson on September 20, 2008. He placed a temporary one that day, and made a herculean effort to return to the summit one week later with a weatherproof ammo can and the journal that remains on the summit today. Barely a handful of people, if any, sign it each year. Before these registers, the peak was referenced only by its height on USGS maps: “Peak 4245 m (13,920+ ft).”

Of course, nothing can prevent people from calling a peak whatever name they choose, and today you can find extensive references to Mt. Morgenson via internet searches, and even its location. But you won’t find an easy route to the top. There is no straightforward trailhead at which to park your car, no defined way to the mountain’s base, and no trail at all to the summit. To get there, you must choose one of several cross-country approaches that seasoned peakbaggers call a dayhike. Most mortals require an overnight, maybe two, for a round-trip, depending upon an eastern or western approach. For our trek in the summer of 2018—the first attempt at climbing Mt. Morgenson for both of us—Rick and I had decided on a long, meandering route that would take us through a little bit of everything Randy loved about the Sierra.

Starting at the sage-scented desert floor of the Owens Valley on a hot July day, our lives slowed down the second we hit the trail. “Half your pace, double your fun” was a piece of advice Rick used to post on trailhead billboards. It was a knowing and encouraging message from a man wired for his job. So when I’d first asked him if he’d guide me on an off-trail “ranger” route to Mt. Morgenson and he told me he was no longer rangering, I was shocked. I’d gotten to know Rick during the research I did for my book, and I’d taken it for granted that he’d be a ranger forever—or at least until his body gave out.

While we ambled up the trail, Rick shared with me the reasons he had not returned to his long-held position as a backcountry ranger the past two summers. He openly described the depression he suffered while coming to terms with his life changes—first and foremost, a baby girl. He and his wife had spent a magical summer in the backcountry with their new daughter Charlotte at Charlotte Lake (no coincidence). But the experience proved logistically difficult, fundamentally at odds with the needs of his family, and financially unsustainable.

What to do? Starting a new career in his mid-50s, after two decades in the mountains, was a challenge. His struggles, like Morgenson’s, offered a glimpse into a hidden side of rangering: What happens when the glory days end? Leaving the ranger ranks and saying goodbye to full summers in the Sierra was more than just losing a job—it was losing a yearly source of emotional, spiritual, and physical rejuvenation. At a time when Rick knew he should be celebrating the life he and his wife had brought into this world, he felt like he was dying inside. He told me that he was “lost like a tenderfoot” out in the so-called “real world.” He recognized that he was now following too closely in his mentor’s footsteps. He said that, like Randy, he had been gazing at the scenery without looking where he was going and suddenly all was dark and disorienting. He had reached out to other ex-rangers for support, one of whom recommended, “just don’t think about the backcountry” and “watch a lot of kitten videos.”

Hearing this, and more, I wondered if inviting Rick on this trip had been such a good idea after all. Was all of this beauty just an ugly reminder? Had the Range of Light gone dark for him? I hoped this trip would help him discover a route, not only to Mt. Morgenson, but for a way forward in life.

The following morning and 6,000 vertical feet later, we topped Sheppard Pass, and were welcomed to the high country with a squall. “Smell that?” Rick said, inhaling deeply, as we pulled ponchos from our packs. “Rain on granite, nothing like it.” And he was off, hustling across the exposed plateau. Thunder growled. Lightning flashed. “We should spread out a couple hundred feet,” he yelled back to me. “If the lightning gets much closer, get up against a rock and sit on your sleeping pad with your knees pulled up to your chest.” He took a few more steps. “Hey, not to freak you out,” he continued, “but if I die up here, I’m good with that.” He inhaled deeply again, and I gave him a thumbs-up.

As a young ranger, Randy wrote about his relationship with the outdoors while on patrol, and now, as Rick led the way off-trail, the words Randy wrote in his 1973 McClure Meadow log came back to me: All of your life, someone is pointing the way, directing you this way and that, determining for you which road is best traveled. Here is your chance to . . . be adventuresome. Don’t forever seek the easiest way. Take the way you find. Don’t demand trail signs and sturdy bridges. Don’t demand we show you the mountains. Seek them and find them yourself. . . This is your birthright as an animal, most commonly denied you. Be free enough from intentions to find goodness wherever you are and in whatever is happening. Here for once in your life you . . . can now live by whim. . . Here’s your one chance to get lost, fall in the creek, find a beautiful place.

A place just like the ridge on which Rick and I stood gazing at Mt. Morgenson, Rick still catching his breath after his spirited charge to spear the balloons. Rising majestically over Wallace Lake, the craggy peak dominates the skyline, appearing taller than Whitney. That’s when Laura Pilewski, the Tyndall Creek backcountry ranger, with 16 seasons as a wilderness ranger and 24 years as a National Park Service employee, came trotting up toward us from the other side. Her pants were soaked from the thighs down from crossing the outlet of the lake while chasing after the same bunch of balloons.

“Rick Sanger, fancy seeing you here,” she joked, giving him a hug.

“Those balloons didn’t stand a chance,” Rick said, as the three of us picked our way down the other side of the ridge to join Laura’s husband, Rob, the Crabtree Meadow ranger, as well as eastern Sierra legend John Dittli, a former park ranger himself, who’s spent nearly four decades exploring and photographing these mountains. On this trip, he was nearing the end of a journey he’d dubbed the Grand Traverse—he intended to travel the park from top to bottom, both the crests and the canyons.

John said this solo cross-country trek had been instigated by his 60th birthday, and that he couldn’t decide if “GT” stood for “grand traverse,” “geezer tour,” or simply a “good time.” It was a two-week, 100-plus-mile trip, and if he kept to his schedule he’d meet us on his eleventh day out: July 26. He had.

Rick had proposed that the five of us come together on the shores of Wallace Lake on this date so we’d be here during the Pilewskis’ scheduled days off. It was something of a fluke that it all came together, for in addition to John’s mileage, both Rob and Laura’s “days off” had been filled with backcountry emergencies for five consecutive weeks, including one cardiac arrest, a climbing fatality, and numerous rescue requests. One “emergency,” however, had proven to be two 20-something backpackers hiking a section of the John Muir Trail, who had become “trapped” at a creek they felt was too perilous to cross and activated their emergency locator beacon. Not knowing the nature of the emergency, Laura had hiked several miles carrying oxygen and a full trauma kit. With a deep breath, she explained to them what a legitimate emergency is and directed them to an easier crossing nearby. Such is the life of a backcountry ranger.

Our plan for the following day was to scramble up the summit of Mt. Morgenson to pay homage to Randy. The prospect of seeing the view from “his” peak was something I’d anticipated for years, and it reminded me of something Alden Nash once told me. When you reach a summit for the first time and spin that slow 360 degrees, he said, “you’re unwrapping the view—it’s not a reward for your efforts. It’s a gift.”

I’d never met John, Laura, or Rob, but by the time I’d pitched my tent and shared a batch of miso, it felt as if I was with long-lost relatives. We all harbored a deep connection to both Randy and these mountains. The Pilewskis had joined the search for Randy, and John had befriended him on his alpine travels. As the sun sank, we gathered on a huge granite slab a couple hundred feet from the lake’s shore, warmth radiating from the rock even while the temperature dropped. Peaks rose several thousand feet above us in all directions. Rob ceremoniously unwrapped two lovely trout he’d caught and smoked for the occasion, their orangey-pinkish flesh on par with the colors that had begun to paint the surrounding summits. Laura added a block of cheese, Rick some hearty crackers, and I unveiled mini bottles of spirits and began mixing powdered-electrolyte cocktails. John, whose bear cannister was nearing the trip-end dregs, searched for something to contribute but finally succumbed to our demands to “stop and eat.”

We raised a cup to Randy, then chatted well into the headlamp hours, rapt as John described his journey through the Window Peak drainage. He’d paused at the giant snow bridge that still spanned the creek in late July, the same type of bridge where many speculate Randy met his end. Hundreds of others had journeyed to that beautiful spot over the years, scratched their heads, and wondered if Randy had fallen through the ice farther upstream. Had his body moved down to the falls during the spring runoff? Or perhaps he’d fallen through the ice bridge, right where his radio had been found, right where John had bent down, peered into the deep, cold, drafty ice cave, and paid his respects.

Or perhaps he hadn’t fallen at all. “The least I owe these mountains is a body,” Randy had said to a fellow ranger after one particularly dicey rescue mission during which he had been hit on the head by rockfall. His helmet had likely saved his life, but he seemed ambivalent about it. When Randy went missing two years later, that quote haunted the rangers.

It was a somber moment of silence in our camp. All of us had visited that spot and contemplated Randy’s end. Randy, 58 at the time of his disappearance, had been struggling with ending his career, which for wilderness rangers is like ending a love story. Eventually, they all must stop—bodies give out, partners want company, 401(k)s need contributions. But then what? Will brief sojourns back into these wilds be enough? That’s the question Rick wanted to answer on this trip.

Gordon Wallace, one of the park’s earliest backcountry rangers, during the 1930s, had summed up the dilemma by warning future rangers, “Do not come and roam here unless you are willing to be enslaved by its charms. Its beauty and peace and harmony will entrance you. Once it has you in its power, it will never release you for the rest of your days.”

The next morning, we began our planned ascent, rambling up the gentle basin, finding grassy ramps that presented themselves like secret passages through a series of granite benches. The sky was clear, but we covered the half-mile approach briskly, fully aware that thunder and lightning were the afternoon trends. Once we reached Wales Lake, more than 2,000 feet below Mt. Morgenson, I was already at the summit in my mind, where I intended to pull out the square of folded paper in my pocket and read aloud a few lines I’d copied from Randy’s logbooks.

We picked our way through the talus and rubble, contouring as we climbed to a ridge that led to the summit. It was classic Sierra scrambling: fun, yet requiring constant attention to shifting rocks. As the lakes began to shrink into ponds and then puddles far below, I felt the excitement swelling in my head—or at least that was how I discounted the first wave of dizziness.

Another few hundred feet of elevation, and the rock beneath my feet swayed, causing me to reach out and steady myself on a waist-high chunk of granite. Testing my footing, I realized it had been that sensation you get at a red light, when the car next to you creeps forward and you slam on your brakes, only to realize you aren’t moving.

A little more altitude and I was no longer thinking about the summit, but rather contemplating how I’d get down. We entered a chute that required a simple class 3 move and I literally hugged the granite. It was steep enough now that every time I looked up to spot the others, a rush of vertigo spun my vision. What’s wrong with you? This isn’t Everest, it’s easy scrambling. You’ve been wanting to do this for how many years? And now you’re here at 13,000 feet—so close, just a few more pushes and you’re there.

I’d never turned away from a Sierra peak in my life. But when a single, white cotton-ball of a cloud drifted in from around the corner of Mt. Morgenson’s upper shoulder and hung there, I started thinking of yesterday’s afternoon squall. From blue sky to the first raindrops had been perhaps 15 minutes. I made my decision and called out, “Hey, Rob—would you think less of me if I just waited here while you guys push on? My head’s not feeling right, and I don’t want to slow you all down, especially if we get a storm.”

“Actually,” said Rob, “I’d think more of you. You’re being really smart. And this is the perfect place for it.”

We made a plan, and Rob—who was in his 27th year as a wilderness ranger—watched as I made my way down toward a gravelly ledge where we would either meet up or I could better see the eastern slope if their descent ended up going that direction. Once I got there, Rob gave me a thumbs-up, and then climbed up and out of sight to catch up with the others.

Looking around for a place to recline and close my eyes, I smelled a distinctly sweet and delicate scent and found myself in a garden of strikingly blue polemonium, which had been Randy’s favorite Sierra flower. I’d only happened upon the high-altitude gem a handful of times, in little more than withered clumps, because I tended to visit the high country in September and October, past the flower’s prime. I had hoped I might see it on this trip, and recalled the story from Randy’s childhood, when he’d climbed a Yosemite peak with his father, Dana, and first discovered polemonium eximium. Dana told Randy that the common name is sky pilot because it is found only on or near the tops of the highest peaks. “The name,” said Dana, “means ‘one who leads others to heaven.’” Randy reached to pluck a tiny bouquet for his mother, but his father had stopped him, explaining how the delicate flowers had fought hard to survive in such a harsh environment. “Wouldn’t it be nice to leave these alone?” He explained in terms an 8-year-old might grasp: “If climbers before us had picked these flowers, we wouldn’t now be enjoying their beauty.”

I sat down amidst the blooms, their presence somewhat mitigating the regret of not summiting, as the others continued upward. It took them 30 minutes to top out, the final push requiring some puzzle work between, up, and over chunks of rock. Rick pulled himself up last and found John standing on the tiniest perch, with thousands of feet of air beneath him.

One by one, they each stood on the summit and unwrapped that 360-degree gift that included a near-eye-level vista of Mt. Whitney to the south and Mt. Russell to the east. Strings of emerald and turquoise lakes, patches of green meadows, and vertical granite formations in every imaginable shade of rust and gray stretched out from the vantage point. Those who have stood atop Mt. Morgenson say the view is among the best in the entire Sierra, and Rick concurred, thrilled at having made it to a place he’d spent months thinking about. “You’re bleeding,” Laura pointed out a gash on Rick’s shin, which he called a “rock kiss,” with a hint of fondness. They signed the register, and the four of them lifted their water bottles, toasting their comrade: “To Randy.”

Some 800 vertical feet below, I remained disappointed, to be sure, but it’s hard to feel too sorry for yourself when you’re reclining in paradise.

No storm moved in, the clouds remained scattered, and in what seemed like no time at all, I heard faint voices on the wind. I could see that the others had descended around the corner and were in the drainage far below, so I made my way down to join them, still feeling funky enough to butt-slide the steeper rock.

I was relieved to be on flat ground and happy for my companions. It occurred to me how appropriate it was that only rangers, past and present, made it to the summit to honor their colleague.

But I was most happy for Rick because he was still grieving, not for Randy, but for this place. He needed the summit more than any of us that day. He needed to know that he could be himself without being a ranger. Was that the lesson Randy was grappling with when he died?

We took it slow back to our tents, pausing at benches peppered with obsidian flakes, wrapping around Wales Lake, and skirting a mountain meadow. A few hours later, in camp, I was getting water when some dark, slender clouds appeared on the craggy skyline rimming our basin. The edge of the storm reached over the ridgeline like a climber’s fingers groping for a hold. And then in an instant, it leapt over and was upon us. I was spellbound by how swiftly the glassy waters of the lake were whipped into an angry sea of whitecaps and by how completely Mts. Russell, Morgenson, and Whitney dissolved into the swirling darkness. After only five minutes, sheets of rain and hail drove the five of us into our tents. Thunder rumbled and when lightning flashed, illuminating the inside of the tent, I began to count. Seven Mississippis later: boom!

After 20 minutes and another four or five lightning strikes, I was lying atop my air mattress when I felt an odd sensation beneath me. Lightning flashed again. One thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three … boom! The ground shook and I turned my head in time to see my empty water bottle as it disappeared under the rain flap, drifting away. Then it struck me: I was floating. Well, I thought to myself, this is embarrassing.

I’d pitched my tent in a flat spot that seemed perfectly angled to drain away any afternoon showers, but I hadn’t anticipated the Biblical proportions of this tempest. The door of my tent faced away from the others, and the storm was so loud and violent, there was no point calling out to see how they were faring. Sitting up, I pulled my knees to my chest and draped my sleeping bag around my neck like a boa as lightning flashed again.

The storm raged for more than an hour, then the pounding rain and hail suddenly stopped. It was replaced by a soft, shimmery sprinkle on the tent walls. Snow.

As lightning continued to touch down around us, I pulled out the sheet of paper I’d meant to read on the summit. In the comfort of my office a week earlier, I’d chosen excerpts from Randy’s writings, and one was especially appropriate considering my sleeping pad was doubling as a flotation device. Randy had always felt the most content when nature was at its wildest.

I don’t wish man in control of the universe, he’d written in 1971 while atop Mt. Solomons. I wish nature in control, and man playing only just a role as one of its inhabitants. I want every blade of grass standing naturally, as it was when pushed through the soil with spring vigor. I want the stones and gravel left in the autumn as spring meltwater left them. Only these natural places, apart from my tracks, give me joy, exhilaration, understanding. What humanity I have has come from my relations with these mountains.

Then it was over.

I climbed out of the tent and looked around, awestruck. The basin was covered in white, the sky was clear and, unexpectedly, so was my head. It was a vision so stunning, I could feel it in my core.

The others joined me, bailing water from their tents as they emerged. More than a century’s worth of Sierra wilderness experience between us, and we’d all been caught off guard by the sheer depth of water that flooded what had seemed to be a sufficiently elevated camp. Rick, who had pitched his tent directly on granite, fared the best and hooted aloud, “Whoooo! What a storm!” He was clearly in his element, and it no longer seemed like being in the mountains reminded him that he soon wouldn’t be. Lowering his voice, he said to me, “You know what? I think I’m going to be OK.”

While John watched the water drain away from his tent, my gaze was drawn toward Mt. Morgenson. It was shining with a soft, pink alpenglow that ignited into a fiery red as I watched. I sighed, maybe more loudly than intended, and realized John was there beside me. He gave me a pat on the back.

Earlier, I’d asked the others how the top had been, and they had kindly avoided gushing over the view. John summed it up with a hand on my shoulder and a bit of wisdom every ranger, and every hiker, should learn to live by. “It’s pretty special, but it’s not going anywhere,” he said. “Another time.”

Eric Blehm is the author of The Last Season, which tells the full of story of Randy Morgenson’s life and disappearance, and which won a National Outdoor Book Award. An excerpt appeared in the 2006 May and June issues of BACKPACKER.