Backpacker Adventure Guide: Weminuche Wilderness

'Lobo to Fourmile Ridge, Steve Howe'

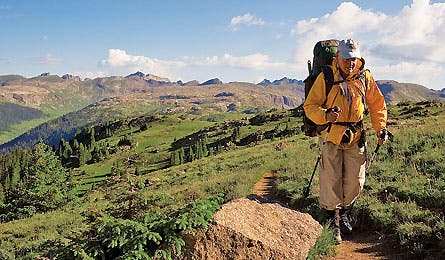

Lobo to Fourmile Ridge, Steve Howe

Descent from Trimble Pass, Steve Howe

Pittsburgh Mine, Steve Howe

Endlich Mesa, Steve Howe

In the way out wild, irony sucks. That’s what I tell Mike as we stand atop Hope Mountain, peering incredulously at an impassable 300-foot cliff that didn’t appear so impassable on our maps. We’ve come to Colorado’s famously rugged Weminuche Wilderness to attempt an eight-day, 50-mile high route, and suddenly–it’s only day three–our whole plan looks anything but hopeful. If we can’t find a way across the ridgeline to Grizzly Peak, my brother and I will go home as empty-handed as most of the prospectors who mined this region a century ago.

“Nice going, chump!” he says, rolling his eyes. The proposed crossing was, after all, my big fat idea.

“The topos looked good,” I protest. “The aerial photos looked good. How was I supposed to know the cliff was overhung?”

Normally our bickering could be chalked up to sibling rivalry or the Lord of the Flies way that Mike and I generally deal with each other. But this col was critical to our planned south-to-north traverse of the Needle Mountains, so the sharp words that follow reflect the bigger problem we’re facing. Set on the southwest edge of the Weminuche, these peaks are said to have the highest average elevation and steepest slopes of any range in the United States–meaning our route alternatives are few.

It’s really Mike’s fault, I decide. My burly, not-so-identical twin is a professor of mathematical physics in Wisconsin–and a serious Colorado junkie. Alaska? Sierra Nevada? Glacier? Fat chance. Despite weeks off every summer, it’s nearly impossible to pry him from Coors country. I normally prefer my trail towns less swank than Colorado’s, and I’m allergic to the state’s legendary scree, but he won’t go anywhere else. So I’d caved, lured by the prospect of punching through the baddest part of the steepest range in Colorado’s biggest wilderness.

We’d decided to find a remote, challenging route–with two requirements. The first was maximum solitude, which eliminated Chicago Basin, a popular bowl with three baggable 14ers and a trailhead accessed via the quaintly historic Durango-Silverton narrow gauge railway. The second was high country–really high country. We wanted to stay above the area’s 11,000-foot timberline. Which all sounded peachy when we were plotting the route onscreen. Now, lacking rope and rappelling gear, we’re rudely reminded of the difference between maps and reality, and how that difference seems to widen the higher and steeper you go.

Hope Mountain may be an ill-named relic of a metal-mad era, but it’s also one mighty scenic relic. From its summit, we can just see the tops of Needle Ridge and Sunlight Peak, craning their necks over the massive ridgeline that drapes from Jupiter Mountain to Grizzly Peak, and on to the tortured slopes of McCauley Peak and Echo Mountain, with their huge northern flanks plunging into Grizzly Basin.

Once the bickering flames out, we start thinking about solutions. The plan–if we can find a detour–is still to forge north along the Needles, then cross the steep Grenadier Range beyond them. From the Grenadiers, we’ll drop into the deep Elk Creek Valley, climb back to the Highland Mary Plateau, then turn northwest and beeline across three more alpine basins before plunging from the ridgelines straight down onto Main Street in the newly hip mine-era hamlet of Silverton.

Seeking to avoid a descent to the loathed lowlands, we look for hope in our topos, but there is none. Folding the maps with a sigh, we turn east and pound 3,600 vertical feet down the Johnson Creek Trail to Vallecito Creek.

There we receive a pleasant surprise. Spring snowslides have wiped out the horse bridge at Vallecito’s southern end. The normally bustling trail is deserted. We enjoy the luxurious solitude and the primo streamside track through deep pine forest. But our return to the alpine zone looks intimidating. The quad shows a series of steep valleys climbing back toward the ridgelines towering overhead–but no relevant trails. Yet from somewhere in my addled memory comes a vague rumor about a track up Sunlight Creek.

With little to lose, we poke around and discover an old climber’s rope strung across Vallecito Creek, probably from some high-water epic. Clue enough. After a 30-yard, knee-deep ford, we strike a well-engineered but long-forsaken trail. Almost immediately, the track disappears beneath a half-mile swath of avalanched timber–karmic payback, perhaps, for our gloating about the bridge washout. For hours, we scramble over, under, and across a jackstraw pile of shredded pine and aspen, finally breaking out onto sweet trail again. Dusting ourselves off, we switchback upwards through shoulder-high wildflowers to Sunlight Lake.

The lake proves to be an idyllic pool set beneath appropriately named Jagged Mountain, and our campsite comes with aerial views back down the valley. It doesn’t take long to settle in and kick back. But later, when Mike’s off on an evening constitutional, I hear him squeal, high-pitched, like some school girl at a Ricky Martin concert. Then, from the same direction, a snow-white mountain goat suddenly appears over the ridge. It seems my erstwhile hermano was in full squat over his appropriately LNT cathole when he spun to find the mature billy five feet away.

I’m not gloating–much–since an identical scenario befell me once in the Sangre de Cristos. Mountain goats don’t have many natural enemies; no predators can handle their vertigo-inducing habitat. Consequently, they often approach people, even licking them for the salt in their sweat.

Up close, which can mean right in your face, mountain goats look unbelievably powerful, like a cross between a cathedral gargoyle and an albino gorilla, all rippling muscles and spiky black devil horns, with dark, inscrutable eyes that hint at chaos. They’re usually peaceful, thank goodness, although people occasionally get gored or humped. Fortunately, this particular billy seems more curious than amorous, staring silently as we pitch camp, then clattering away into the high cirques.

From Sunlight Lake, we’re back on plan A, popping across high passes near the range crest, and rounding Leviathan Peak with timberline far below our boots. This is what we came for: secret alpine valleys, peaks like broken gray tusks, and cliff-bound passes narrow as axe chops. Toward dusk, we throw down beneath Storm King Peak, bivvying on a small bench just short of our next pass. The perch comes with an expansive view of the stony Grenadier Range, with Vestal, Arrow and Electric, its towering fortresses of 2 billion-year-old quartzite, spaced like turrets on a castle wall.

Endless boulders take us down to rockbound Lake Silex, then we wrap north again across tundra passes toward Trinity Creek. Descending sun-warmed cliff bands to the stream, we’re stymied by a steep gully filled with rock-hard ice, but a narrow game trail traverses left, so we take it. There we run into a large Outward Bound group out of Silverton. They’re in high drama mode, several students struggling with the exposed ledges.

We yak briefly with the instructors, then continue up wide-open tundra, listing the beautiful but bureaucratically named mountains we pass: Peak Seven, Peak Six, Peak Five, then 4-3-2-1. On cue, rain overtakes us at the last saddle before our descent to Elk Creek, an excellent excuse to boogie down toward the deep gorge and an intersection with the Colorado Trail.

Here in the comparative lowlands at 10,300 feet, horseflies and hikers both swarm, so after a short mile of bustling track, we diverge onto ladder-steep elk paths, climbing north through ravines that spiral up to the Highland Mary Plateau. Several calf-stretching hours later, as dusk sets in, we stumble onto an old hunter’s camp perched on a tiny bench.

Spent Winchester cartridges surround a small fire circle and an ancient, humongous wood pile, all of it overlooking the vast gulf of Elk Creek and the bulky form of Peak Two, now bathed in the last rays of alpenglow. Mike and I would normally avoid combusting this cache of cellulose, but it’s been a tough day, and our cheery little campfire goes well with the whiskey we pass back and forth, cowboy-style.

On the Highland Mary Plateau, we strike a motherlode of wildflowers. Horizon to horizon, the meadows are blanketed in scarlet paintbrush, brilliant purple asters, white marsh marigolds, and clusters of pale blue columbine. We rollercoaster over broad gray passes and flowered basins, crossing north out of the Weminuche Wilderness and scrambling down clattery slate ridges to the abandoned mine shafts of Spencer Basin.

Some chunks of rusted iron and a few shallow, collapsed tunnels stand out from the thin tundra, and there are old hints of half-roads switchbacking up thru the wildflowers. All are faint reminders of the brief but intense silver boom that raged here after the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, which authorized the government to purchase $2 to $4 million in silver annually to mint coinage.

Silverton saw 2,000 prospectors that first year, and the town soon boasted 40 saloons. But life was tough even when things were good. Cemetery records from that era paint a bleak picture of mining camp life: 117 deaths from snowslides, 143 from miner’s consumption, 161 from pneumonia, 202 from mine accidents, 138 from flu.

Silver prices soared again in 1890, when the Sherman Act doubled government purchases. Just as quickly, though, Congress repealed the law, resulting in massive sell-offs and the Silver Panic of 1893. Overnight, most camps turned to ghost towns. To this day, minefields of abandoned tunnels sit throughout the San Juans, many of them dangerously unstable, others leaching toxic drainage.

It’s no coincidence that deep veins of metal ore and high, steep slopes are found together here. The combination resulted from an intense volcanic period 20 to 40 million years ago, when this region became a moonscape of lava flows, ash falls, and collapsing magma craters 20 miles wide. The La Garita volcano had one of the most violent eruptions ever known, with a blast-kill zone that extended to present-day Kansas. The crater, though well-hidden by subsequent erosion, is now believed to be earth’s largest known caldera.

But it was ice, not fire, that shaped the Needles and Grenadiers into their dizzying current form. When vast glacial plateaus melted off the ranges 15,000 years ago, they were left with “over-steepened” slopes, more precipitous than the angle of repose (that is, the angle at which loose objects begin to tumble). The result: dizzying climbs and legendary winter avalanches.

We get some drama of our own that afternoon in Spencer Basin. Cowering beneath our tarp, we watch a lightning show worthy of Zeus pound the ridges above us. Then, emerging into a wet, cleansed world, we cross our highest passes yet, sucking deep lungfuls of rain-washed air. An airy goat traverse leads to our final camp, high above Arrastra Basin. Below, a ghost town sits perched on a peninsula of tailings that juts into Silver Lake. According to my GPS, my head passes the 13,000-foot level whenever I stand up.

From the downy comfort of our sleeping bags, we admire the artillery flash of distant thunderstorms and toast our success, assuming it’s just a downhill cruise to Silverton, where we’re anxious to wallow in all sorts of boomtown corruption. The last day, however, finds us struggling on vanished trail, through rib-high thickets of bluebells, fragrant but slick as grease, then long slopes of loose, tippy boulders, and one final bushwhack.

The forest spits us out onto a dirt road just as the sky begins flashing again. Above the rustle of Gore-Tex, the hiss of zippers, and the dynamite slap of thunder, we hear the tooting whistle of a steam locomotive. Yeehaw! It’s Saturday night in the old mining town, and we’re getting close. Suited up, we set off through the spitting hail, beelining for Silverton’s saloon district, two wilderness prospectors who just struck it rich.

HIKE IT

Weminuche High Route

Retrace the author’s trip through the heart of a fabled wilderness.

This 50.5-mile hike runs south-to-north across Endlich Mesa, Silver Mesa, the Needle Mountains, the Grenadier Range, the Highland Mary Plateau, and Arrastra and Spencer Basins before plunging straight into downtown Silverton. Along the way, you’ll encounter spectacular plateaus of rolling tundra, ripsaw ridges, cliff-ringed lakes, and lush midsummer wildflowers, but it’s not a route for the lazy or unacclimatized. For most of its length, you’ll wander up and down through a succession of steep passes, rarely dropping below 12,000 feet. Budget at least seven days; peakbagging and side hikes beg for more time. About half of the route requires off-trail routefinding. We recommend downloading the author’s track log and waypoints from backpacker.com/hikes for map-plotting or GPS use. Despite often steep terrain, there’s no exposed scrambling that requires ropes–unless you go in spring, when an ice axe and/or crampons would also be useful for steep snow.

The Way

From Main Street in Durango, turn north onto 15th South Street near the Animas River bridge. This funnels you onto Florida Road. Continue 13.8 miles on Florida Road, then turn left to Lemon Reservoir on County Road 2431/FR 596. Twenty-one miles from town, turn right onto FR 597, which quickly becomes a high-clearance road. Continue 10.6 slow, uphill miles to the Endlich Mesa trailhead. The route ends in downtown Silverton.

Maps

Trails Illustrated 140 Weminuche Wilderness, and USGS topos Columbine Pass, Storm King Peak, Howardsville, and Silverton

More Weminuche Hikes

Lobo to Fourmile Ridge

Start high and stay high on this Continental Divide traverse.

This 36.5-mile hike stays at or above timberline for most of its course around the Cimarron Creek headwaters in Weminuche’s southeastern corner. Beginning at 11,800 feet near Wolf Creek Pass, it follows the CDT north, then west along high ridges to Piedra Pass. Minimal climbing makes this stretch feasible even for flatlanders. From the Piedra River headwaters, you climb south on the Turkey Creek Trail across benchlands with excellent views of rugged Red Mountain, and fine camping at scenic Turkey Creek Lake. Along the way, keep an eye out for large elk herds in the Puerto Blanco region. From there, drop through an increasingly lush, timbered valley on the Fourmile Trail, passing several gigantic waterfalls before ending your journey in aspen groves north of Pagosa Springs. Budget at least four days.

The Way

Begin at Lobo Overlook, beneath the radio towers atop Wolf Creek Pass, north of Pagosa Springs on US 160. End at Fourmile trailhead: From Main Street in Pagosa Springs, turn north onto N. 5th Street, which turns into Fourmile Road; go 12.5 miles to road’s end.

Map

Trails Illustrated 140 Weminuche Wilderness. USGS topos Wolf Creek Pass, South River Peak, Palomino Mountain, and Pagosa Peak

Waypoints

13S 0334202E 4154775N Spotted Lake, scenic camp for first night

13S 0322250E 4154191N Red Mountain panoramas; watch for elk

13S 0319533E 4145773N Views of huge waterfalls & Eagle Mountain

West Needles Wilderness Area

Summit a handful of rugged 13ers while basecamping at timberline tarns for a weekend or more.

The massive, metamorphic West Needle Mountains form the core of a 28,740-acre parcel of land added to the Weminuche Wilderness in 1995. From Molas Pass, you get an excellent overview of this pristine alpine landscape, which glaciers scraped into a wildland of aesthetic rock slabs and pocket lakes. Four 13,000-foot peaks–Snowdon, Twilight, North Twilight, and West Needle–makes this a peakbagger’s paradise. The six-mile approach trail ends at popular Crater Lake, but there’s plenty of lonelier low-impact camping among slabs dotted with ponds in the miles beyond. Adventurous hikers can depart the Crater Lake approach trail and strike cross-country 1.3 miles to isolated lakes west of Snowdon Peak. Another scenic and adventurous trip is to cross the saddle east of Crater Lake and traverse southwest to an unnamed pond in Twilight Cirque. There you’ll get a primo balcony view east across the Animas River Gorge to the main Needles Range. Short trips don’t get any better than this.

The Way

Crater Lake Trail #623 starts from the Andrews Lake Day Use Area, off milepost 63, just South of Molas Pass on US 550 between Silverton and Durango.

Map USGS topo Snowdon Peak

Waypoints

13S 0261607E 4175976N Isolated lakes southwest of Snowdon Peak

13S 0261430E 4172737N Good camping at tarn NE of Crater Lake

13S 0260360E 4171741N Quiet lakeside camp below Twilight Peaks

Trip Planner – Weminuche Wilderness

Season July through late September

Getting There Silverton is 127 miles (3 hours) from Grand Junction, CO, via US 50 and US 550 over steep, winding Red Mountain Pass. Durango lies another 47 miles (1 hour) south of Silverton via US 550 over Molas Pass.

Car Camping

Lots of informal Forest Service sites are available to people with 4WD vehicles. Inquire at the nearest USFS office for site-specific regulations. For 2WD vehicles, campgrounds are located at Haviland Lake and Purgatory on US 550 between Durango and Silverton, at Transfer Park and Florida Recreation Area on Florida Creek Road, and at West Fork and Wolf Creek on US 150 north of Pagosa Springs.

Cautions

High altitude, lightning, tough river crossings, and steep unstable slopes abound. Black bears live throughout most of the Weminuche, so proper food storage is mandatory. Mountain goats occasionally gore people; do not approach them.

Guidebook

Hiking Colorado’s Weminuche and South San Juan Wilderness Areas, by Donna Ikenberry, $17

Permits & Regulations No permits required, but LNT camping is a must. Set up at least 100 feet from water, disperse wastewater, and ask rangers about closed lakeside sites and other local restrictions.

Contact San Juan National Forest: (970) 247-4874. Pagosa Springs Ranger District (year-round): (970) 264-2268.

Silverton Public Lands Center (summer only): (970) 387-5530; www.fs.fed.us/r2/sanjuan/